India bars protests that support the Palestinians. Analysts say a pro-Israel shift helps at home

THEY ARE BOTH ISLAMOPHOBES

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, right gestures and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu waves to the media as they arrive for a meeting in New Delhi, India, Jan.15, 2018. Modi, a staunch Hindu nationalist, was one of the first global leaders to swiftly express solidarity with Israel and call the Hamas attack “terrorism.” Modi became the first Indian prime minister to visit Israel in 2017. Netanyahu, travelled to New Delhi the following year and called the relationship between New Delhi and Tel Aviv a “marriage made in heaven.”

BY AIJAZ HUSSAIN AND SHEIKH SAALIQ

November 7, 2023

SRINAGAR, India (AP) — From Western capitals to Muslim states, protest rallies over the Israel-Hamas war have made headlines. But one place known for its vocal pro-Palestinian stance has been conspicuously quiet: Indian-controlled Kashmir.

Indian authorities have barred any solidarity protest in Muslim-majority Kashmir and asked Muslim preachers not to mention the conflict in their sermons, residents and religious leaders told The Associated Press.

The restrictions are part of India’s efforts to curb any form of protest that could turn into demands for ending New Delhi’s rule in the disputed region. They also reflect a shift in India’s foreign policy under populist Prime Minister Narendra Modi away from its long-held support for the Palestinians, analysts say.

India has long walked a tightrope between the warring sides, with historically close ties to both. While India strongly condemned the Oct. 7 attack by the militant group Hamas and expressed solidarity with Israel, it urged that international humanitarian law be upheld in Gaza amid rising civilian deaths.

But in Kashmir, being quiet is painful for many.

“From the Muslim perspective, Palestine is very dear to us, and we essentially have to raise our voice against the oppression there. But we are forced to be silent,” said Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, a key resistance leader and a Muslim cleric. He said he has been put under house arrest each Friday since the start of the war and that Friday prayers have been disallowed at the region’s biggest mosque in Srinagar, the main city in Kashmir.

Anti-India sentiment runs deep in the Himalayan region which is divided between India and Pakistan and claimed by both in its entirety. In 2019, New Delhi removed the region’s semiautonomy, drastically curbing any form of dissent, civil liberties and media freedoms.

Kashmiris have long shown strong solidarity with the Palestinians and often staged large anti-Israel protests during previous fighting in Gaza. Those protests often turned into street clashes, with demands for an end of India’s rule and dozens of casualties.

Modi, a staunch Hindu nationalist, was one of the first global leaders to swiftly express solidarity with Israel and call the Hamas attack “terrorism.” However, on Oct. 12, India’s foreign ministry issued a statement reiterating New Delhi’s position in support of establishing a “sovereign, independent and viable state of Palestine, living within secure and recognized borders, side by side at peace with Israel.”

Two weeks later, India abstained during the United Nations General Assembly vote that called for a humanitarian cease-fire in Gaza, a departure from its usual voting record. New Delhi said the vote did not condemn the Oct. 7 assault by Hamas.

“This is unusual,” said Michael Kugelman, director of the Wilson Center’s South Asia Institute.

India “views Israel’s assault on Gaza as a counterterrorism operation meant to eliminate Hamas and not directly target Palestinian civilians, exactly the way Israel views the conflict,” Kugelman said. He added that from New Delhi’s perspective, “such operations don’t pause for humanitarian truces.”

India’s foreign minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, sought to justify India’s abstention.

“It is not just a government view. If you ask any average Indian, terrorism is an issue which is very close to people’s heart, because very few countries and societies have suffered terrorism as much as we have,” he told a media event in New Delhi on Saturday.

Even though Modi’s government has sent humanitarian assistance for Gaza’s besieged residents, many observers viewed its ideological alignment with Israel as potentially rewarding at a time when the ruling party in New Delhi is preparing for multiple state elections this month and crucial national polls next year.

The government’s shift aligns with widespread support for Israel among India’s Hindu nationalists who form a core vote bank for Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party. It also resonates with the coverage by Indian TV channels of the war from Israel. The reportage has been seen as largely in line with commentary used by Hindu nationalists on social media to stoke anti-Muslim sentiment that in the past helped the ascendance of Modi’s party.

Praveen Donthi, senior analyst with the International Crisis Group, said the war could have a domestic impact in India, unlike other global conflicts, due to its large Muslim population. India is home to some 200 million Muslims who make up the predominantly Hindu country’s largest minority group.

“India’s foreign policy and domestic politics come together in this issue,” Donthi said. “New Delhi’s pro-Israel shift gives a new reason to the country’s right-wing ecosystem that routinely targets Muslims.”

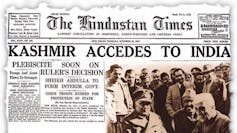

India’s foreign policy has historically supported the Palestinian cause.

In 1947, India voted against the United Nations resolution to create the state of Israel. It was the first non-Arab country to recognize the Palestinian Liberation Organization as the representative of the Palestinians in the 1970s, and it gave the group full diplomatic status in the 1980s.

After the PLO began a dialogue with Israel, India finally established full diplomatic ties with Israel in 1992.

Those ties widened into a security relationship after 1999, when India fought a limited war with Pakistan over Kashmir and Israel helped New Delhi with arms and ammunition. The relationship has grown steadily over the years, with Israel becoming India’s second largest arms supplier after Russia.

After Modi won his first term in 2014, he became the first Indian prime minister to visit Israel in 2017. Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, travelled to New Delhi the following year and called the relationship between New Delhi and Tel Aviv a “marriage made in heaven.”

Weeks after Netanyahu’s visit, Modi visited the occupied West Bank city of Ramallah, a first by an Indian prime minister, and held talks with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas. “India hopes that Palestine soon becomes a sovereign and independent country in a peaceful atmosphere,” Modi said.

Modi’s critics, however, now draw comparisons between his government and Israel’s, saying it has adopted certain measures, like demolishing homes and properties, as a form of “collective punishment” against minority Muslims.

Even beyond Kashmir, Indian authorities have largely stopped protests expressing solidarity with Palestinians since the war began, claiming the need to maintain communal harmony and law and order.

Some people have been briefly detained by police for taking part in pro-Palestinian protests even in states ruled by opposition parties. The only state where massive pro-Palestinian protests have taken place is southern Kerala, which is ruled by a leftist government.

But in Kashmir, enforced silence is seen not only as violating freedom of expression but also as impinging on religious duty.

Aga Syed Mohammad Hadi, a Kashmiri religious leader, was not able to lead the past three Friday prayers because he was under house arrest on those days. He said he had wanted to stage a protest rally against “the naked aggression of Israel.” Authorities did not comment on such house arrests.

“Police initially allowed us to condemn Israel’s atrocities inside the mosques. But last Friday they said even speaking (about Palestinians) inside the mosques is not allowed,” Hadi said. “They said we can only pray for Palestine — that too in Arabic, not in local Kashmiri language.”

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, right gestures and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu waves to the media as they arrive for a meeting in New Delhi, India, Jan.15, 2018. Modi, a staunch Hindu nationalist, was one of the first global leaders to swiftly express solidarity with Israel and call the Hamas attack “terrorism.” Modi became the first Indian prime minister to visit Israel in 2017. Netanyahu, travelled to New Delhi the following year and called the relationship between New Delhi and Tel Aviv a “marriage made in heaven.”

BY AIJAZ HUSSAIN AND SHEIKH SAALIQ

November 7, 2023

SRINAGAR, India (AP) — From Western capitals to Muslim states, protest rallies over the Israel-Hamas war have made headlines. But one place known for its vocal pro-Palestinian stance has been conspicuously quiet: Indian-controlled Kashmir.

Indian authorities have barred any solidarity protest in Muslim-majority Kashmir and asked Muslim preachers not to mention the conflict in their sermons, residents and religious leaders told The Associated Press.

The restrictions are part of India’s efforts to curb any form of protest that could turn into demands for ending New Delhi’s rule in the disputed region. They also reflect a shift in India’s foreign policy under populist Prime Minister Narendra Modi away from its long-held support for the Palestinians, analysts say.

India has long walked a tightrope between the warring sides, with historically close ties to both. While India strongly condemned the Oct. 7 attack by the militant group Hamas and expressed solidarity with Israel, it urged that international humanitarian law be upheld in Gaza amid rising civilian deaths.

But in Kashmir, being quiet is painful for many.

“From the Muslim perspective, Palestine is very dear to us, and we essentially have to raise our voice against the oppression there. But we are forced to be silent,” said Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, a key resistance leader and a Muslim cleric. He said he has been put under house arrest each Friday since the start of the war and that Friday prayers have been disallowed at the region’s biggest mosque in Srinagar, the main city in Kashmir.

Anti-India sentiment runs deep in the Himalayan region which is divided between India and Pakistan and claimed by both in its entirety. In 2019, New Delhi removed the region’s semiautonomy, drastically curbing any form of dissent, civil liberties and media freedoms.

Kashmiris have long shown strong solidarity with the Palestinians and often staged large anti-Israel protests during previous fighting in Gaza. Those protests often turned into street clashes, with demands for an end of India’s rule and dozens of casualties.

Modi, a staunch Hindu nationalist, was one of the first global leaders to swiftly express solidarity with Israel and call the Hamas attack “terrorism.” However, on Oct. 12, India’s foreign ministry issued a statement reiterating New Delhi’s position in support of establishing a “sovereign, independent and viable state of Palestine, living within secure and recognized borders, side by side at peace with Israel.”

Two weeks later, India abstained during the United Nations General Assembly vote that called for a humanitarian cease-fire in Gaza, a departure from its usual voting record. New Delhi said the vote did not condemn the Oct. 7 assault by Hamas.

“This is unusual,” said Michael Kugelman, director of the Wilson Center’s South Asia Institute.

India “views Israel’s assault on Gaza as a counterterrorism operation meant to eliminate Hamas and not directly target Palestinian civilians, exactly the way Israel views the conflict,” Kugelman said. He added that from New Delhi’s perspective, “such operations don’t pause for humanitarian truces.”

India’s foreign minister, Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, sought to justify India’s abstention.

“It is not just a government view. If you ask any average Indian, terrorism is an issue which is very close to people’s heart, because very few countries and societies have suffered terrorism as much as we have,” he told a media event in New Delhi on Saturday.

Even though Modi’s government has sent humanitarian assistance for Gaza’s besieged residents, many observers viewed its ideological alignment with Israel as potentially rewarding at a time when the ruling party in New Delhi is preparing for multiple state elections this month and crucial national polls next year.

The government’s shift aligns with widespread support for Israel among India’s Hindu nationalists who form a core vote bank for Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party. It also resonates with the coverage by Indian TV channels of the war from Israel. The reportage has been seen as largely in line with commentary used by Hindu nationalists on social media to stoke anti-Muslim sentiment that in the past helped the ascendance of Modi’s party.

Praveen Donthi, senior analyst with the International Crisis Group, said the war could have a domestic impact in India, unlike other global conflicts, due to its large Muslim population. India is home to some 200 million Muslims who make up the predominantly Hindu country’s largest minority group.

“India’s foreign policy and domestic politics come together in this issue,” Donthi said. “New Delhi’s pro-Israel shift gives a new reason to the country’s right-wing ecosystem that routinely targets Muslims.”

India’s foreign policy has historically supported the Palestinian cause.

In 1947, India voted against the United Nations resolution to create the state of Israel. It was the first non-Arab country to recognize the Palestinian Liberation Organization as the representative of the Palestinians in the 1970s, and it gave the group full diplomatic status in the 1980s.

After the PLO began a dialogue with Israel, India finally established full diplomatic ties with Israel in 1992.

Those ties widened into a security relationship after 1999, when India fought a limited war with Pakistan over Kashmir and Israel helped New Delhi with arms and ammunition. The relationship has grown steadily over the years, with Israel becoming India’s second largest arms supplier after Russia.

After Modi won his first term in 2014, he became the first Indian prime minister to visit Israel in 2017. Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, travelled to New Delhi the following year and called the relationship between New Delhi and Tel Aviv a “marriage made in heaven.”

Weeks after Netanyahu’s visit, Modi visited the occupied West Bank city of Ramallah, a first by an Indian prime minister, and held talks with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas. “India hopes that Palestine soon becomes a sovereign and independent country in a peaceful atmosphere,” Modi said.

Modi’s critics, however, now draw comparisons between his government and Israel’s, saying it has adopted certain measures, like demolishing homes and properties, as a form of “collective punishment” against minority Muslims.

Even beyond Kashmir, Indian authorities have largely stopped protests expressing solidarity with Palestinians since the war began, claiming the need to maintain communal harmony and law and order.

Some people have been briefly detained by police for taking part in pro-Palestinian protests even in states ruled by opposition parties. The only state where massive pro-Palestinian protests have taken place is southern Kerala, which is ruled by a leftist government.

But in Kashmir, enforced silence is seen not only as violating freedom of expression but also as impinging on religious duty.

Aga Syed Mohammad Hadi, a Kashmiri religious leader, was not able to lead the past three Friday prayers because he was under house arrest on those days. He said he had wanted to stage a protest rally against “the naked aggression of Israel.” Authorities did not comment on such house arrests.

“Police initially allowed us to condemn Israel’s atrocities inside the mosques. But last Friday they said even speaking (about Palestinians) inside the mosques is not allowed,” Hadi said. “They said we can only pray for Palestine — that too in Arabic, not in local Kashmiri language.”

KHASMIR IS INDIA'S GAZA

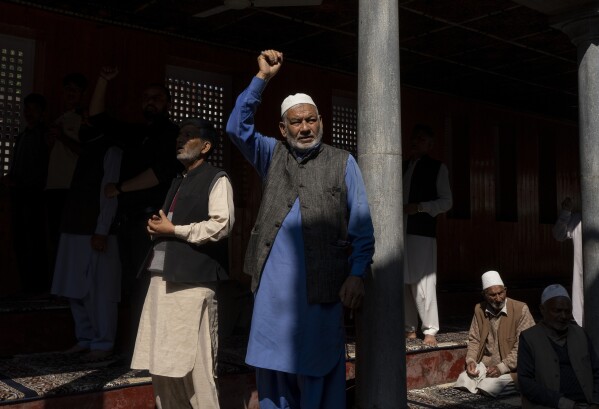

Kashmiris pray for Palestinians killed in Israel’s military operations in Gaza, inside a mosque in Budgham, northeast of Srinagar, Indian controlled Kashmir, Oct. 13, 2023. In Indian-controlled Kashmir, known for its vocal pro-Palestinian stance, authorities have barred any solidarity protest and asked Muslim preachers not to mention the conflict in their sermons. Analysts say the new restrictions on speech reflect a shift in India’s foreign policy under the populist Prime Minister Narendra Modi away from its long-held support for the Palestinians. (AP Photo/ Dar Yasin, File)

Activists of Socialist Unity Center of India (Communist) burn an effigy of U.S. President Joe Biden and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu during a rally to protest against Israel’s military operations in Gaza and to show solidarity with the Palestinian people, in Kolkata, India, Nov. 1, 2023. Indian authorities have largely stopped protests expressing solidarity with Palestinians since the war began, claiming the need to maintain communal harmony and law and order. Some people have been briefly detained by police for taking part in pro-Palestinian protests even in states ruled by opposition parties. (AP Photo/Bikas Das, File)

-People hold placards in solidarity with Israel in Ahmedabad, India, Oct. 16, 2023. In Indian-controlled Kashmir, known for its vocal pro-Palestinian stance, authorities have barred any solidarity protests. Analysts say the new restrictions on speech reflect a shift in India’s foreign policy under the populist Prime Minister Narendra Modi away from its long-held support for the Palestinians. The government’s shift aligns with widespread support for Israel among India’s Hindu nationalists who form a core vote bank for Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party. (AP Photo/Ajit Solanki, File)

An elderly Kashmiri shouts slogans against Israel’s military operations in Gaza, inside a mosque in Budgham, northeast of Srinagar, Indian controlled Kashmir, Oct. 13, 2023. In Indian-controlled Kashmir, known for its vocal pro-Palestinian stance, authorities have barred any solidarity protest and asked Muslim preachers not to mention the conflict in their sermons. Analysts say the new restrictions on speech reflect a shift in India’s foreign policy under the populist Prime Minister Narendra Modi away from its long-held support for the Palestinians. (AP Photo/ Dar Yasin, File)

A student activist resists detention while gathering to protest against Israel’s military operations in Gaza and to support the Palestinian people, in New Delhi, India, Oct. 27, 2023. Indian authorities have largely stopped protests expressing solidarity with Palestinians since the war began, claiming the need to maintain communal harmony and law and order. Some people have been briefly detained by police for taking part in pro-Palestinian protests even in states ruled by opposition parties. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri, File)

Kashmiris pray for Palestinians killed in Israel’s military operations in Gaza, inside a mosque in Budgham, northeast of Srinagar, Indian controlled Kashmir, Oct. 13, 2023. In Indian-controlled Kashmir, known for its vocal pro-Palestinian stance, authorities have barred any solidarity protest and asked Muslim preachers not to mention the conflict in their sermons. Analysts say the new restrictions on speech reflect a shift in India’s foreign policy under the populist Prime Minister Narendra Modi away from its long-held support for the Palestinians. (AP Photo/ Dar Yasin, File)

Activists of Socialist Unity Center of India (Communist) burn an effigy of U.S. President Joe Biden and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu during a rally to protest against Israel’s military operations in Gaza and to show solidarity with the Palestinian people, in Kolkata, India, Nov. 1, 2023. Indian authorities have largely stopped protests expressing solidarity with Palestinians since the war began, claiming the need to maintain communal harmony and law and order. Some people have been briefly detained by police for taking part in pro-Palestinian protests even in states ruled by opposition parties. (AP Photo/Bikas Das, File)

-People hold placards in solidarity with Israel in Ahmedabad, India, Oct. 16, 2023. In Indian-controlled Kashmir, known for its vocal pro-Palestinian stance, authorities have barred any solidarity protests. Analysts say the new restrictions on speech reflect a shift in India’s foreign policy under the populist Prime Minister Narendra Modi away from its long-held support for the Palestinians. The government’s shift aligns with widespread support for Israel among India’s Hindu nationalists who form a core vote bank for Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party. (AP Photo/Ajit Solanki, File)

An elderly Kashmiri shouts slogans against Israel’s military operations in Gaza, inside a mosque in Budgham, northeast of Srinagar, Indian controlled Kashmir, Oct. 13, 2023. In Indian-controlled Kashmir, known for its vocal pro-Palestinian stance, authorities have barred any solidarity protest and asked Muslim preachers not to mention the conflict in their sermons. Analysts say the new restrictions on speech reflect a shift in India’s foreign policy under the populist Prime Minister Narendra Modi away from its long-held support for the Palestinians. (AP Photo/ Dar Yasin, File)

A student activist resists detention while gathering to protest against Israel’s military operations in Gaza and to support the Palestinian people, in New Delhi, India, Oct. 27, 2023. Indian authorities have largely stopped protests expressing solidarity with Palestinians since the war began, claiming the need to maintain communal harmony and law and order. Some people have been briefly detained by police for taking part in pro-Palestinian protests even in states ruled by opposition parties. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri, File)

___

Find more of AP’s Asia-Pacific coverage at https://apnews.com/hub/asia-pacific

AIJAZ HUSSAIN

Hussain is a correspondent based in Kashmir, India

SHEIKH SAALIQ

Saaliq is a reporter based in New Delhi, India

Find more of AP’s Asia-Pacific coverage at https://apnews.com/hub/asia-pacific

AIJAZ HUSSAIN

Hussain is a correspondent based in Kashmir, India

SHEIKH SAALIQ

Saaliq is a reporter based in New Delhi, India