Illustration: Priyanka Borar.

“I remember rats falling down from roofs and dying in our homes. It was the most ominous sight I have ever seen. You might laugh at it today, but a rat falling from the roof meant we had to leave our houses, not knowing when we could return.”

That vivid and graphic account comes from A. Kuzhandhaiammal, a resident of Kalapatti locality in Coimbatore. Now in her 80s, she was not yet in her teens when plague struck that Tamil Nadu city for the last time, in the early 1940s.

Coimbatore’s unhappy history of epidemics – ranging from smallpox to plague to cholera – has seen the rise of a phenomenon that exists elsewhere but seems concentrated in this region. The proliferation of ‘Plague Mariamman’ temples. There are 16 of them in this city.

And, of course, the Covid-19 pandemic has seen the coming of a ‘Corona Devi’ temple as well. But it is the Plague Mariamman (also called Black Mariamman) shrines that command a far greater following. There are a few in neighbouring Tiruppur district too that still hold festivals and attract visitors.

From 1903 to 1942, Coimbatore suffered at least 10 bouts of plague, killing thousands of people. Decades after it left, plague remains etched in the collective memory of this city. For many old-timers like Kuzhandhaiammal, the mention of plague is a chilling reminder of what the city historically lived through.

Outside of what is perhaps the most famous of the Plague Mariamman temples in the bustling Town Hall area, a flower seller is readying for a busy evening. “Today is Friday. There will be a good turnout,” says Kanammal, in her 40s, without lifting her eyes from hands that continue to intricately weave the flowers together.

“She is powerful, you know. It doesn’t matter that we have a Corona Devi temple now. Black Mariamman is one of us. We will continue to worship her, especially when we fall sick, but even for other kinds of general prayers too,” says Kanammal. By ‘general prayers’ she refers to the more routine demands of devotees – prosperity, success and long life. Kanammal was born nearly four decades after the end of the plague era. But many of her generation, too, flock to Mariamman for succour.

The impact of plague was such that it came to constitute a part of Coimbatore’s cultural ethnography. “The original native residents of the town were not just witnesses to the havoc wrecked by plague. They were the victims. You will not find one family here that has not been affected by plague,” says Coimbatore-based writer C.R. Elangovan.

According to the 1961 District Census Handbook , Coimbatore city witnessed 5,582 deaths in 1909, and 3,869 deaths in 1920 from different bouts of plague. Other reports suggest that Coimbatore’s population was reduced to 47,000 in 1911 after the plague outbreak of that year. All in all, heavy tolls on a city that in 1901 had a population of around 53,000.

Elangovan says his own family fled Coimbatore to briefly “live in the forests” before they could hope to return to the city “without being harmed.” That hope came from what seems an unlikely source today.

“Through those dark years, with no medical help available, people turned to divinity,” reasons P. Siva Kumar, a Coimbatore-based entomologist with a keen interest in the district’s ethnography.

That hope, as so often happens, was also tied to fear and despair. It was in 1927, the middle of the city’s plague era, that the philosopher Bertrand Russell declared religion to be “based primarily and mainly upon fear. It is partly the terror of the unknown and partly the wish to feel that you have a kind of elder brother who will stand by you in all your troubles and disputes.”

All these varied reasons have something to do with the existence of those 16 temples dedicated to the deity – whose popular name, too, underwent a shift. “People also started calling Plague Mariamman as Black Mariamman,” says Elangovan. “And since maari also means black in Tamil, the transition was seamless.”

And even as the plague itself retreats into the shadows of history, generationally handed-down memories of its impact manifest in diverse ways.

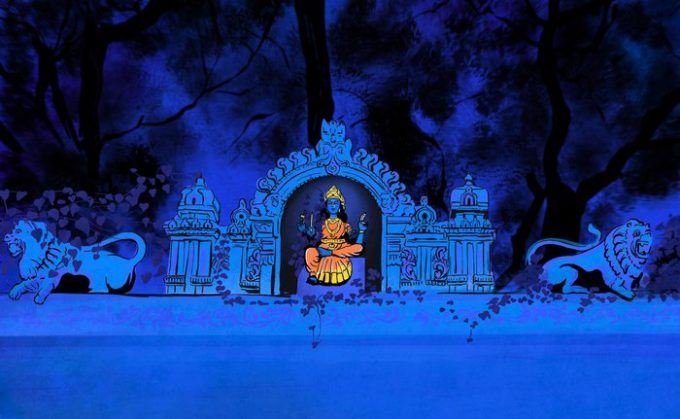

People turn to Plague Mariamman for prosperity and long life, but they also seek relief from diseases like chicken pox, skin ailments, viral infections, and now Covid-19. PHOTO • KAVITHA MURALIDHARAN.

“I remember my parents taking me to the temple whenever I was ill,” says Nikila C., 32, a resident of Coimbatore. “My grandmother made regular visits to the temple. My parents believed that the temple’s holy water would help cure disease. They also offered pujas at the shrine. Today, when my daughter is unwell, I also do the same. I take her there and do pujas , and give her the holy water. I may not be as regular as my parents were, but I still go. I think it is part of being a resident of this city.”

“I serve as a fourth-generation priest here and people still visit seeking remedies for chicken pox, skin diseases, Covid-19 and viral infections,” says M. Rajesh Kumar, 42, at the Plague Mariamman temple in Town Hall area. “There is a belief that this goddess offers reprieve from such diseases.”

“This temple has been in existence for over 150 years. When the plague visited Coimbatore [1903-1942], my great-grandfather decided to consecrate an additional idol as Plague Mariamman. After him, my grandfather and my father took care of it. I do it today. Since then, no region under the reign of the goddess has been affected by plague. And so people have continued to have faith in her.”

A similar story surrounds the temple in Coimbatore’s Saibaba Colony. “This one was originally constructed about 150 years ago,” says 63-year-old V.G. Rajasekaran, an administrative committee member of the Plague Mariamman temple in this locality. That is, it was built before the advent of plague.

Interestingly, both these and many others like them, were already Mariamman temples, but celebrating her in other roles or avatars . When the plague hit this region, bringing devastation in its wake, additional statues of the deity were consecrated – all of them in stone – as Plague Mariamman.

When plague hit the city some three decades after the founding of the temple he serves, “at least five or six people died in each family,” says Rajasekaran. “The families left their homes after the deaths of their members, or as the plague progressed, when rats fell from the roofs. It took four or five months before they could return to their homes.”

The residents of Saibaba Colony, then a small village, decided to install a separate statue towards worship for cure from plague and decided to call her Plague Mariamman. “We had two deaths in our family. When my uncle fell ill, my grandmother brought him to the temple, laid him before Plague Mariamman, and applied neem and turmeric on him. He was cured.”

Since then, that village and several others (which are now part of Coimbatore city), believed that worshipping Mariamman would save them from the plague.

Elangovan says this could be the reason behind the prolific numbers of, and proximity between, the Plague Mariamman shrines. “Saibaba Colony, Peelamedu, Pappanaickenpalayam, Town Hall and other localities would have been different villages a century ago. Today all of them are part of Coimbatore city.”

Writer and chronicler of Tamil cultural history Stalin Rajangam says the worship of Plague Mariamman could have been a “very natural consequence, a reaction to a disease that had wreaked havoc. The concept of the belief is this: you believe in god to find a solution to your problems, to your worries. The biggest problem for humankind has been illness. So, obviously, belief centres around relief from diseases.”

“It is common in Christianity and Islam too,” Rajangam adds. “Children are treated in mosques for illnesses. In Christianity, we have worship of Arogya Madha (mother of well-being). The Buddhist bhikus are known to have practiced medicine. In Tamil Nadu, we have the siddhars , who were originally medical practitioners. That is why we have something called the siddha stream of medicine.”

There is a Mariamman temple in almost every village of Tamil Nadu. She may have a different name in some regions, but her shrines are there. The idea of particular gods and their wrath or ability to cure is not restricted to one religion or one country. And scholars across the globe have taken the religious response to plagues and epidemics more seriously in recent decades.

A temple in the Pappanaickenpudur neighbourhood of Coimbatore. Painted in red, the words at the entrance say, Arulmigu Plague Mariamman Kovil (‘temple of the compassionate Plague Mariamman’). PHOTO • KAVITHA MURALIDHARAN.

As the historian Duane J. Osheim puts it in his paper,

Religion and Epidemic Disease , published in 2008: “There is no single or predictable religious response to epidemic disease. Nor is it correct to assume religious responses are always apocalyptic. It might be better to recognize that religion, like gender, class, or race, is a category of analysis. The religious response to epidemic disease may best be seen as a frame, a constantly shifting frame, to study influencing illness and human responses to it.”

Annual amman thiruvizhas (festivals for Mariamman) are quite common in Tamil Nadu even today. And these reinforce the need to understand the relationship between public health and religious belief, says Stalin Rajangam. The festivals typically happen across the state in amman temples during the Tamil month of Aadi (mid-July to mid-August).

“The preceding months – Chithirai , Vaigasi and Aani [respectively, mid-April to mid-May, mid-May to mid-June, and mid-June to mid-July] are very hot in Tamil Nadu,” says Rajangam. “The land is dry, and the bodies are dry. The dryness leads to a disease called ammai (chickenpox/smallpox). The remedy for both is coolness. And that is what the thiruvizhas are all about.”

In fact, the worship of ‘Muthu Mariamman’ – yet another role for the deity – is about seeking providential relief from chickenpox and smallpox. “Because the disease leads to outbreaks on skin, the goddess was called Muthu Mariamman, muthu meaning pearl in Tamil. There have been medical advancements that effectively deal with the poxes, yet the temples continue to draw crowds.”

Rajangam also points to some rituals associated with the festivals that could have medicinal if not scientific value. “Once the thiruvizha is announced in a village, a ritual called kaapu kattuthal is held, following which people cannot step outside of the village. They will have to maintain hygiene within their families, on their streets, and in the village. Neem leaves, considered a disinfectant, are liberally used during the festivals.”

The guidelines announced for Covid-19, when the scientific community was still grappling with a solution, was something similar, points out Rajangam. “There was physical distancing and use of sanitisers for hygiene. And in some cases, people resorted to using neem leaves because they did not know what else they could do when Covid happened.”

The idea – of isolation and the use of some kind of sanitiser – is universal. During the Covid outbreak, public-health officials in Odisha invoked the example of Puri Jagannath to drive home the importance of quarantine and physical distancing. The authorities highlighted how Lord Jagannath shuts himself up in theanasar ghar (isolation room) before the annual Rath Yatra.

And the idea of the goddess and fighting disease is “so universal that an amman temple in Karnataka is dedicated to AIDS,” says writer S. Perundevi, associate professor of religious studies at New York’s Siena University,

She adds that Mariamman worship is a “very comprehensive idea … In fact, in Tamil maari also means rain. In certain rituals like mulaipari (an agricultural festival), Mariamman is seen and worshiped as crops. In some cases, she is worshipped as gems. So, she is also seen as the goddess who gives the disease, the disease itself, and its cure. This is what had happened in [the case of] plague too.” But Perundevi warns against romanticising the disease. “The folklore of Mariamman,” she points out, “is more an attempt to accept an encounter with disease as part of life and find solutions.”

So who is Mariamman?

This Dravidian deity has long fascinated researchers, historians, and folklorists.

Mariamman was and is perhaps the most popular goddess in the villages of Tamil Nadu, where she is regarded as the guardian deity. And her stories are as varied as the sources they come from.

Some historians cite Buddhist tradition as recognising her as a Buddhist nun from Nagapattinam, to whom disease-afflicted people, particularly those stricken by smallpox, turned to for a cure. She asked them to have faith in the Buddha and cured very many, treating them with neem-leaf paste and prayer – and advice on hygiene, cleanliness and charity. On her attaining Nirvana, people built a statue of her, and there, holds tradition, begins the Mariamman story.

There are several other versions, too. There is even the tale of the Portuguese, when they came to Nagapattinam, naming her Maryamman and claiming her to be a Christian goddess.

And there are some who claim her to be just a counterpart of Shitala, the north-Indian goddess of smallpox and other infectious diseases. Shitala (‘one who cools’ in Sanskrit) is seen as an incarnation of Goddess Parvati, spouse of Lord Shiva.

But evidence emerging from research of the past few decades suggests she was a goddess of rural people, worshipped by Dalits and the marginalised castes – in fact, a deity of Dalit origin.

Unsurprisingly, the power and appeal of Mariamman saw, over the ages, attempts at assimilation and appropriation of the deity by the dominant castes.

As the historian and writer K.R. Hanumanthan pointed out in a paper, The Mariamman Cult of Tamil Nadu , as early as 1980: “That Mariamman is an ancient Dravidian goddess worshipped by the early inhabitants of Tamil Nadu … is revealed by the association of the deity with the Pariah [Paraiyars, a Scheduled Caste], erstwhile ‘untouchables’ and the oldest representatives of the Dravidian people of Tamil Nadu.

In many temples of this deity, says Hanumanthan, Paraiyars “seem to have acted as the priests for quite a long time. For example, in the Karumariamman temple of Thiruverkadu near Chennai. The original priests were Paraiyars. But they were later replaced by Brahmins when the Religious Endowments Act [1863] came into practice.” This British colonial Act gave legal sanction to an upper-caste takeover of the temples of marginalised communities that was already underway. Post-Independence, states like Tamil Nadu brought in their own laws in an attempt to undo or mitigate this injustice.

And now a ‘Corona Devi’ temple? Seriously?

Well, yes, says Anand Bharathi, manager of the temple of that name in the Coimbatore suburb of Irugur. “It is in line with the Plague Mariamman worship,” he says. “When we decided to install a statue for Corona Devi [in an already existing shrine], the disease was at its peak. And we believe only worship can save us.”

So when Covid-19 happened, Coimbatore was among the few places in the country that saw, in late 2020, a place of worship spring up for the disease.

But Devi? Why not Corona Mariamman, we ask. Well, Bharathi finds there are problems with the lexical semantics of connecting those words. “The word Mariamman sits well with plague but not with Corona. So, we decided to call the goddess Devi instead.”

There is a Mariamman temple in almost every village of Tamil Nadu. She may have a different name in some regions, but her shrines are there

Medical advancements notwithstanding, worship of the deity and the associated rituals continue to be a part of the public response to health issues.

But unlike in the case of Plague Mariamman temples, the Corona Devi temple has not, for most of its existence, allowed worshippers to visit in person – because of the lockdowns. Apparently, a temple built around the deadly virus has to treat not just its deity but the pandemic’s protocols, too, as divine. The temple administration claims it performed a yagna (a ritual worship or offering with a specific objective) for 48 days following which the clay statue of Corona Devi was dissolved in a river. The shrine is now open to visitors, but they might be unnerved by the absence of a figurine to worship.

Writers like Elangovan reject the idea of the Corona Devi temple being part of Coimbatore’s ethos in the way that Plague Mariamman temples are. “It is at best a publicity stunt. It has nothing to do with Plague Mariamman shrines, you cannot draw comparisons between them. Plague Mariamman temples are an intrinsic part of Coimbatore’s history and culture.”

Plague Mariamman places of worship across the city continue to draw crowds to this day, even though plague itself remains just a bleak if awful memory. In 2019, just before the onset of Covid-19, the Plague Mariamman temple at Pappanaickenpalayam became a minor sensation after a parrot sat on the statue of the goddess during a festival, sending devotees into a tizzy.

According to local reports, the ‘event’ lasted for hours, drawing even more visitors to the temple. “Mariamman is a village deity. Her temples will never lose their relevance among the ordinary public,” says Elangovan. “For example, for the Koniyamman temple festival at Town Hall, the sacred fire pit is made at the Plague Mariamman temple in the same locality. The rituals are inter-related. Koniyamman is considered the guardian deity of Coimbatore.”

Not many members of the present generation are aware of such intricate history and myths. Yet, these shrines continue to hold significance for them. “I honestly never knew the temples had this kind of history,” says R. Narain, a 28-year-old entrepreneur in Coimbatore. “But I am a regular visitor to the temple along with my mother, and I will continue to visit it in future too. It changes nothing for me. Or maybe, I will be more awed now.”

This first appeared on Rural India Online.