Marx’s value theory, multidimensional imperialism and ecological breakdown: Interview with Güney Işıkara and Patrick Mokre

Güney Işıkara and Patrick Mokre are authors of Marx’s Theory of Value at the Frontiers: Classical Political Economics, Imperialism and Ecological Breakdown. Işıkara is Clinical Associate Professor of Liberal Studies at New York University, whose research focuses on ecological breakdown and alternative modes of organising production and reproduction. Mokre is a guest researcher at the Economics of Inequality institute in the Vienna University of Business and Economics (WU), whose studies centre on the political economy of labour, inequality and capitalism.

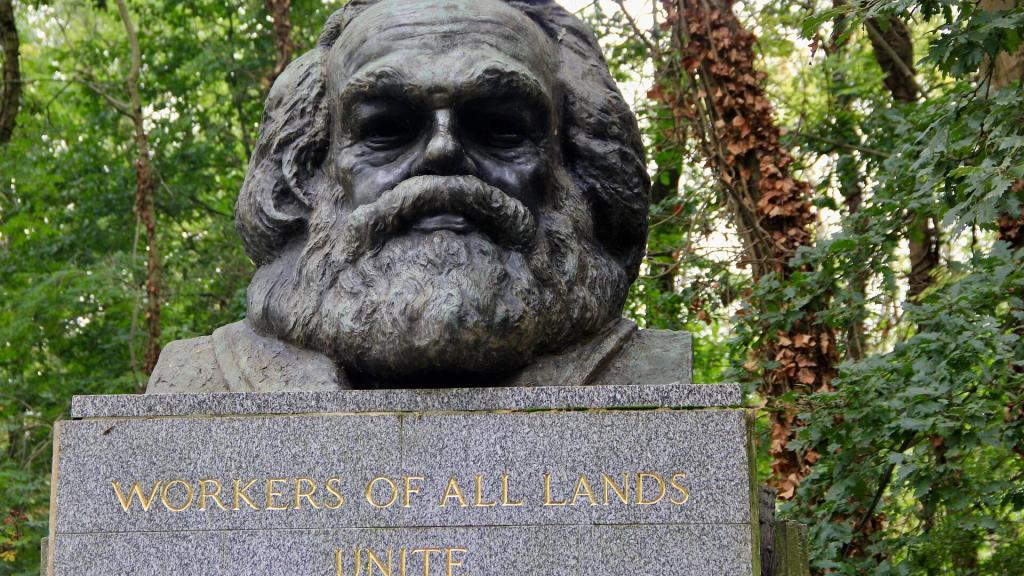

In this interview with Federico Fuentes for LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal, Işıkara and Mokre discuss imperialism’s multidimensional nature, how Karl Marx’s value theory helps explain its economic core and why a value-theoretical framework for studying the global economy is urgently needed.

This interview is the latest in LINKS’ ongoing series on imperialism today.

Discussions regarding imperialism often refer to Vladimir Lenin’s pamphlet on the subject. How do you define imperialism? Do you see Lenin’s concept as still valid? What, if any, elements of Lenin’s concept have since been superseded?

Imperialism shapes the global economy today like no other factor, and that is perfectly clear to most working people around the world. Outsourcing of production, volatile prices of imported goods, exchange rate-induced inflation, foreign investors pushing down wages or domestic capitalists invoking international competition to do the same, debt service on (private and sovereign) foreign debt, and so forth — for most of the global population, imperialism’s effects are felt in everyday life. That does not make its dynamics any less complicated, however.

We see imperialism as the mode of operation of international capital accumulation, rooted in the same dynamics that define capitalism: surplus value production through labour exploitation, which is then reinvested to accumulate and outgrow competitors. Imperialism is a complex, multidimensional phenomenon inherent in the concept of capital as self-expanding value.

It appears as a system of asymmetric economic, political and military power relations that are difficult to distinguish descriptively and separate analytically. It is a mistake therefore to treat these dimensions independently of each other.

From its start, the capitalist mode of production has been international. Its expansion across borders adopted and transformed pre-existing patterns of trade, colonisation and exploitation. When capitalism became the dominant mode of production — first in certain regions and eventually globally — it became clear that internationalisation was an innate feature of capital accumulation, generating specific forms of domination.

Historically, the internationalisation of capital took place in all three functional forms of capital: commodity capital, money capital and production capital. Each phase, however, gave rise to distinct empirical patterns of power relations, along with corresponding waves of imperialism theories.

Lenin’s intervention came at a crucial moment amid World War I — an unprecedented event driven by capital’s expansionist dynamics. It is worth noting that his pamphlet Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism (subtitled A Popular Outline) was intended as a survey of empirical evidence from advanced capitalist countries. It largely supported previous arguments by John A Hobson (in 1902) and Nikolai Bukharin (written in 1915 and published in 1917).

The emphasis on capital exports was a timely intervention as the internationalisation of productive capital was starting to appear on an unprecedented scale. Capital exports remain a central channel of economic imperialism today. Just consider cross-border ownership structures and so-called foreign direct investment in productive capital, which formed Lenin’s point of departure, or the dominance of a few financial centres over credit and debt worldwide.

We also value that Lenin grounded his explanation of the drive toward capital exports in the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, rather than in problems of realisation or theories of underconsumption.

On the other hand, what was largely missing from the first wave of imperialism theories (roughly the first two-to-three decades of the 20th century) was a sustained attempt to link the study of imperialism — or the internationalisation of capital — to the law of value. Henryk Grossman and Otto Bauer were notable exceptions. Both sought to analyse international transfers of value between regions and countries. This line of inquiry then remained surprisingly dormant until it was revived by Arghiri Emmanuel in the late 1960s.

Your latest book explains how Karl Marx’s value theory can help us better understand the economics of imperialism. Can you outline why?

As we see it, imperialism is the way capitalism functions on the international stage. It is essentially what happens when capital accumulation crosses borders and encounters historically structured unequal development, patterns of domination, and asymmetric power relations. Therefore the economic core of imperialism follows the broader logic of capital accumulation and reproduction, which is precisely what value theory helps explain.

Since the early 20th century, attempts to theorise imperialism have evolved alongside imperialism’s development, or more broadly, alongside the changing patterns of internationalised accumulation.

At the start of the 20th century, Rudolf Hilferding, Bukharin and Lenin emphasised exports of productive capital, while Bauer and Grossmann examined power imbalances and transfers of value through trade.

After World War II, many peripheral countries formally decolonised but found themselves subject to new forms of dependency. Kwame Nkrumah coined the term neo-colonialism, Walter Rodney described underdevelopment as an active process driven by the imperialist centre, and, importantly, Emmanuel viewed value transfers as a regular and necessary outcome of international competition.

In the 1990s, when financial deregulation was imposed on the periphery and capital exports increasingly took the form of money capital, Marxist scholars debated financialisation and currency hierarchies.

Binding these different approaches is their common grounding in Marxist theory. Our argument is that value theory can serve as the unifying thread. In the book, we explore one specific dimension of the economics of imperialism by expanding the concept of international value transfers, since these transfers express and reinforce the inequalities structured and reproduced through capitalist competition.

Although the book focuses on the quantitative dimensions of Marx’s value theory — also known as the labour theory of value — we emphasise that this is much more than a quantitative tool. It investigates the law of value, which captures the processes that make the reproduction of capitalist society possible.

Capitalist society is fragmented into private, autonomous units making decisions under competitive pressures, with only partial information and without any mechanism of prior coordination. Marx’s value theory therefore lets us analyse a wide range of phenomena, including capitalist alienation and commodity fetishism, among others.

The labour theory of value examines how production and the social division of labour are regulated by value, particularly from a quantitative perspective. It starts with the creation of value through socially necessary labour time (direct prices), to surplus value’s redistribution in conditions of capitalist competition (prices of production reflecting a general rate of profit), and finally to market prices as indicators of day-to-day shifts in market conditions.

We construct a large dataset of direct prices, prices of production and market prices, and analyse both the regular relationships among these three sets and the systematic deviations between them.

A central thread in the economics of imperialism is the redistribution of surplus value across industries and borders, as well as the appropriation of surplus value produced by workers in one country by capitalists in another. Productive forces in the neo-colonial periphery — outside the traditional colonial and imperial centres — remain underdeveloped and capitals in the centre are powerful enough to mobilise entire states in their interests. Therefore huge redistributions of value occur.

These occur through several channels: the mobility of productive capital (including profit repatriation) and portfolio investment; the capture of value generated in productive industries in one country by non-productive sectors (finance, real estate and so on) in others; and transfers of value across industries and countries through the equalisation of profit rates, that is through the formation of international prices of production.

We examine the last mechanism in detail, focusing on cross-nation and cross-industry differences in the value composition of capital and in rates of surplus value. This line of research had largely faded from Marxist debates after the 1910s, until revived by Emmanuel in his seminal book, Unequal Exchange.

We develop a coherent value-theoretical framework for analysing international transfers of value and, for the first time, present empirical estimates covering a large number of countries over a significant time period. One of our key findings is that aggregate value transfers — representing only one mechanism of economic imperialism — were more than 70 trillion euros between 1995–2020, with gains concentrated in a small group of countries while the majority experienced losses.

This approach’s central strength lies in treating imperialism as an integral part of capitalist competition at the international level, rather than attributing global inequalities to imperfections in an otherwise smoothly functioning capitalism or relying on theoretically eclectic foundations.

In recent times Marxists have sought to incorporate ecology into their understanding of imperialism, raising concepts such as “unequal ecological exchange”. How can Marx’s ideas help us integrate ecology into the concept of imperialism?

The idea of unequal ecological exchange (also called ecologically unequal exchange) emerged from a particular critique of Marx’s value theory. The argument is that Marxist analyses of international trade focus primarily on transfers — and unequal exchanges — of labour values, which are seen as only one form of energy, while overlooking the asymmetric flows of raw materials, land and other forms of energy.

From a broader perspective, it is certainly true that global capitalism's functioning favours the imperial core in terms of the redistribution of surplus value, as well as the appropriation and use of various forms of use value. To describe such processes, Marx used the notion of a “system of robbery,” borrowing the term from German scientist Justus von Liebig, to explain how soil degradation in the countryside accompanied the rise of industrial capitalism in the cities. He also referred to colonial relations in discussing how the dynamics of capital accumulation in England exhausted Irish soil for more than a century.

In recent decades, many studies have analysed international trade through environmental indicators such as ecological footprint (the amount of ecologically productive land area per capita), land or space embodied in commodities, physical trade balances and material flows. These are important contributions because they document the material enrichment of the imperial core at the expense of workers and peasants in the periphery — a key dimension of imperialism.

It is a mistake, however, to think that such material flow patterns have self-constituted dynamics. A defining feature of capitalism is that social and environmental concerns are subordinated to capital accumulation. Social structures and use values — whether from non-capitalist production or non-human nature — are reduced to their usefulness for accumulation and often degraded or destroyed in the process.

Think of a river that offers many use values: it provides enjoyment for swimmers, an ecosystem for fish and algae, and a vital function in the water–groundwater–precipitation cycle, while also serving as a cooling source for data centres. Once its cooling function is fully exploited, the discharged water returns hot and polluted, riverbeds and currents shift, fish and plant life die off, and the water becomes unsafe for recreation. The contradiction between use and exchange value thus lies at the heart of ecological breakdown.

We cannot explain the global distribution of materials, land, energy, space and waste without a coherent theory of accumulation and its relationship to use values. This is precisely what Marx’s value theory provides through the duality of use value and exchange value — a contradiction embedded in every commodity.

The original imperialist powers built their wealth and military might on colonial conquest and pillage of pre-capitalist societies. How have the mechanisms of imperialist exploitation changed over time? Are these countries still the main imperialist powers today?

There is a striking continuity between the pre-capitalist colonial empires and the power centres of contemporary imperialism. Colonial trade and slavery helped fuel industrialisation and the genocidal expropriation of Indigenous lands that accompanied that transition.

However, pre-capitalist colonialism and contemporary imperialism operate through different economic dynamics. The most powerful country in today’s imperial core, the United States, was not a colonial empire in the classical sense but itself a colony. Conversely, once-dominant colonial empires, such as Spain and England, are now far more marginal. Historical continuities exist, but they should not be overstated: colonialism and imperialism follow distinct economic logics.

Under capitalism, capital accumulation is the driving force. Because of this process's internal contradictions, the most advanced capitals in a country eventually run up against limits shaped by the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

At the same time, they are powerful enough to mobilise their state apparatuses to support their interests abroad. By investing in countries with older and less efficient capitals, lower wages, weaker regulation and generally lower levels of competition, they secure higher profit rates, at least temporarily. They also deploy economic power alongside military, diplomatic and political resources to suppress competitive threats and keep productive forces in other regions underdeveloped.

The dominant mechanisms of international capitalism have shifted over time. Before the 20th century, former colonial empires and emerging imperialist states primarily used the periphery as a source of cheap resources — often close to outright plunder — and cheap or enslaved labour.

A major shift occurred with the large-scale export of capital commodities, not simply for sale to foreign capitalists but as a means to outsource production while retaining ownership. Capital exports generated substantial profit flows from the periphery back to industries in the imperialist countries.

Immediate after World War II, profitability in the imperial centre was a less pressing problem, while formal decolonisation of colonies became central. During this period, a consolidated world market, in which the periphery depended on importing consumer and capital goods while exporting agricultural products and raw materials, grew in importance. This led to significant international transfers of value.

In the 1990s, capitalism was re-introduced in many parts of the world. The imperialist core remained the only viable trading partner, one restructured through the neoliberal backlash to eroding profitability in the 1960s and ’70s. This led to a wave of global deregulation and liberalisation, and the globalisation of financial institutions from the imperialist core exporting capital in financial form and consolidating various forms of dependency.

This is a simplified timeline, but there are two essential points. First, capital exports — in commodity, productive and money form — have always been central to imperialism. One mechanism of economic imperialism emerging does not eliminate others.

For example, value transfers arising from the existence of a world market do not disappear just because value capture linked to money capital becomes more prominent. It remains a single capitalist system, constantly evolving in pursuit of higher profits under conditions of real competition. Analysing imperialism today means examining all mechanisms of dominance, while considering possible countervailing forces.

Second, the economics of imperialism primarily describe capital-to-capital — or, more simply, industry-to-industry — relationships, rather than relations between nations treated as homogeneous entities. Different segments of capital also compete within nations, often over whose interests the state advances. Consider, for instance, tensions between manufacturing industries in the US, which have lost ground during the US-led expansion of global markets, and the tech sector, which has benefited enormously from enforcing technological property rights in formally open markets.

For this reason, we reserve analytical categories such as exploitation for the social relationship between capital and labour — that is, between capitalists and workers — rather than relations between countries. The study of imperialism, while centred on the international dimensions of capital accumulation, cannot be reduced to relations between nations abstracted from class conflict.

Your research shows China is one of the world’s biggest winners in terms of value transfers. Yet China’s per capita GDP is far behind the wealthiest countries. How should we categorise China’s global status? What are the economic foundations and specific features that help explain China’s position? And how should we understand the growing US-China conflict, particularly as their economies are more integrated than ever?

Providing some context for our results is helpful here. Our dataset covers the period 1995–2020, and at the start of this period China occupied a subdominant position. In the 1990s, China accounted for a much smaller share of global output than today, with a low value composition of capital and a high rate of surplus value. Through both channels, it transferred value to the imperialist core.

In the early 2000s, China’s capital composition began to converge toward the global average, and it became a recipient of value transfers through that mechanism. In the early 2010s, a similar shift took place with the rate of surplus value. China’s transition from net loser to net recipient coincides with the Global Financial Crisis, roughly in 2010, and it has maintained this advantageous position since.

During the same period, our results show a relative setback for the US, particularly in terms of value composition. To us, this aligns with broader developments: China’s relative stability, its sustained capitalisation and its rise to global leadership in several key industries contrasted with a turbulent decade in the US economy, economically and politically.

We should stress, however, that our figures only refer to transfers of value resulting from the formation of international prices of production. They do not capture other major mechanisms of economic imperialism, such as the role of non-production industries in appropriating value created abroad, capital exports, advantages linked to currency hierarchies and similar dynamics.

It is reasonable to assume that the US, along with other core imperialist countries, still enjoy significant advantages in these areas, which are not analysed in this book. We plan to extend our research using a coherent value-theoretical framework to examine these extra dimensions and provide a more comprehensive empirical picture.

And then, beyond economics, there is also political and military power. As the US faces relative economic decline — or, more precisely, as it is more directly challenged by China economically — it has mobilised its political and military capacities more frequently and assertively. In strictly military terms, the US still holds clear and substantial supremacy.

For that reason, we do not believe that our findings are enough to conclude that China is already an imperialist power or that it is fully on par with the US as an imperialist rival. What we show is that China has shifted its position in one central dimension of imperialism. That shift is significant and substantial, but not, on its own, enough to determine China’s overall position within the imperialist world system.

Conversely, Russia, which many label as imperialist due to its use of military power abroad, remains a net loser in terms of value transfer. Where do you see Russia fitting into the imperialist North/Global South divide?

With the same caveats mentioned earlier — that the analysis in the book is partial and provisional — our findings indicate that Russia is not a net recipient of international value transfers. That does not mean, however, that it is necessarily a net loser in all other dimensions of economic imperialism.

Nor does it imply that Russia holds a subordinate military position, whether regionally or globally. Our analysis needs to be deepened and extended to extra mechanisms through which value is captured and appropriated on a global scale. We intend to pursue this.

We see the world economy, as well as global political and military power structures, as still dominated by the conventional imperialist countries — above all the US and its G7 allies. At the same time, our analysis of global capitalism is grounded in the concept of real competition. At both micro and macro levels, relations of domination are continuously contested, largely due to capitalism’s internal contradictions. Challenging powers may succeed or fail, and these processes often unfold over long historical periods.

Imperialism is therefore not only a relationship of domination between imperialist and neo-colonial countries. It also involves rivalries within the dominant bloc, as well as competition among neo-colonial countries striving to improve their relative positions.

Over time, a country’s economic and military capacities may erode to such an extent that maintaining its political standing within the imperial bloc becomes its main objective. Conversely, a country may strengthen economically — China is an obvious example — and begin challenging established hierarchies primarily through economic channels, while remaining militarily subordinate and excluded from the core political alliances upholding the existing order.

What do these examples — along with those of countries such as Australia, Taiwan and South Korea, which are generally viewed as part of the imperialist camp yet are net losers in terms of value transfers — tell us about the reliability of focusing on just one or a few economic indicators (value transfers, labour productivity, GDP per capita, etc) to determine a country’s status in the world today? Also, have you encountered any issues in using available economic data to establish results that are meaningful for Marxist economics/value theory?

This question goes straight to the heart of how we understand imperialism — and, more broadly, value theory itself. We are always dealing with counteracting forces and internal contradictions, and these force us to look beyond any single indicator.

Take Taiwan. Taiwanese capital, as a whole, appears as a net giver in terms of value transfers. At the same time, its semiconductor industry is not only internationally competitive but in many respects technologically dominant. However, this strength is concentrated largely in one sector, and that sector remains highly dependent on demand from the tech industries of China and the US.

Value transfers linked to the value composition of capital — where Taiwanese semiconductor producers are clearly in a recipient position — may be offset by value losses in other industries. This reflects Taiwan’s subdominant position within the broader alliance of imperialist countries.

South Korea is somewhat different. It has a relatively diversified production structure, with most major industries domestically owned. Like Germany, South Korea appears as a net giver of international value transfers, yet it also runs a strong trade surplus. In other words, the disadvantages it faces in one mechanism of economic imperialism may be counterbalanced — or even outweighed — by advantages in another.

In the book, we did not systematically analyse ownership structures or trade balances; comparing these different channels remains a future task. But these examples illustrate the broader point: relying on one variable is not enough to determine a country’s position within global capitalism.

Imperialism is shaped by multiple, interacting mechanisms. That is precisely why we believe developing a coherent and consistent value-theoretical framework for studying the global economy is not only useful, but urgently needed.

Considering all of this, what should 21st century anti-imperialist internationalism look like?

Quite frankly, we wrote a book in which one chapter examines two of the many core economic channels of imperialism. When it comes to anti-imperialist internationalism, much more than academic research is needed; solidarity and resistance must also take practical forms.

That said, we believe our work can offer insight into potential choke points and broader structural dynamics — especially for those who are critical of the concentration of power in a small group of imperialist countries or concerned about the growing risk of destructive imperialist wars.

First, we find no evidence supporting the claim, common in the 1970s, that imperialism primarily relies on wage differentials that materially privilege workers in imperialist countries. Depending on one’s position in the debate, this may seem trivial or counterintuitive. But it also weakens the claim — associated with thinkers such as Emmanuel — that international solidarity between workers in neo-colonial and imperialist countries is structurally unviable. On the contrary, as the social contract in the imperial core — relative stability in exchange for relative comfort — gives way to declining living standards, precarious employment, offshoring and increased migration driven by war and deprivation, solidarity across borders and passports becomes more necessary.

Second, the international value transfers we analyse are largely the outcome of the very existence of a world market. In its most basic form, capitalism generates uneven development and widening inequalities. This casts doubt on world market-oriented reforms or capitalist-state-sponsored strategies to mitigate such inequalities. Reforming capitalism at an international scale to tame its social and environmental ills is the greatest illusion right now, where its contradictions are so sharpened that international conventions and laws are increasingly null and void.

Third, it is evident that the imperialist core is ramping up military expenditures, driven both by internal contradictions and by intensifying competition over the strategic inputs required for capital accumulation — rare earths, lithium, copper, cobalt, and similar resources. The drive to directly subordinate the periphery’s resources to the needs of the imperial centre is intensifying.

From the standpoint of these countries, the struggle for national liberation and sovereignty remains as relevant as ever. At the same time, unconditional and practical solidarity from the working classes and socialists within imperialist countries remains indispensable.