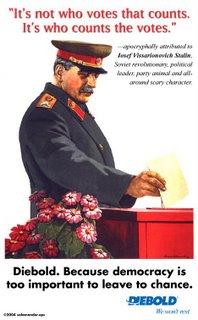

"Fascism should more properly be called corporatism because it is the merger of state and corporate power." - Benito Mussolini

Corporatism is a form of class collaboration put forward as an alternative to class conflict, and was first proposed in Pope Leo XIII's 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum, which influenced Catholic trade unions that organised in the early twentieth century to counter the influence of trade unions founded on a socialist ideology. Theoretical underpinnings came from the medieval traditions of guilds and craft-based economics; and later, syndicalism. Corporatism was encouraged by Pope Pius XI in his 1931 encyclical Quadragesimo Anno.

Gabriele D'Annunzio and anarcho-syndicalist Alceste de Ambris incorporated principles of corporative philosophy in their Charter of Carnaro.

One early and important theorist of corporatism was Adam Müller, an advisor to Prince Metternich in what is now eastern Germany and Austria. Müller propounded his views as an antidote to the twin "dangers" of the egalitarianism of the French Revolution and the laissez-faire economics of Adam Smith. In Germany and elsewhere there was a distinct aversion among rulers to allow unrestricted capitalism[citation needed], owing to the feudalist and aristocratic tradition of giving state privileges to the wealthy and powerful[citation needed].

Under fascism in Italy, business owners, employees, trades-people, professionals, and other economic classes were organized into 22 guilds, or associations, known as "corporations" according to their industries, and these groups were given representation in a legislative body known as the Camera dei Fasci e delle Corporazioni. See Mussolini's essay discussing the corporatist state, Doctrine of Fascism.

Similar ideas were also ventilated in other European countries at the time. For instance, Austria under the Dollfuß dictatorship had a constitution modelled on that of Italy; but there were also conservative philosophers and/or economists advocating the corporate state, for example Othmar Spann. In Portugal, a similar ideal, but based on bottom-up individual moral renewal, inspired Salazar to work towards corporatism. He wrote the Portuguese Constitution of 1933, which is credited as the first corporatist constitution in the world.

When you get rid of the paramilitary uniforms, the swaggering macho bravado, fascism is merely corporatism. And like its economic predecessor Distributism it shares a Catholic origin, a fetish for private property, and being a Third Way between Capitalism and Socialism. After WWI Corporatism, Distributism, and Social Credit, evolved as economic ideologies opposed to Communism and Capitalism.

Corporatism is sometimes identified as State Capitalism which it is a form of. However State Capitalism is a historic epoch in Capitalism that developed as a response to the Workers rebellions world wide between 1905-1921, in particular the Bolshevik Revolution. The epoch of State Capitalism begins with Keynes rescue of capitalism by using the State to prime the pump and to provide social reforms in response to the revolutionary workers movement.

Key features of the theory of state-capitalism.

1. A new stage of world capitalism

Dunayevskaya wrote that: “Each generation of Marxists must restate Marxism for itself, and the proof of its Marxism lies not so much in its “originality” as in its “actuality”; that is, whether it meets the challenge of the new times” The theory of state-capitalism met the challenge of the day in its universality, it was not narrowed to a response to the transformation of the Russian Revolution into its opposite, but of a new stage of world capitalism. She argued that: “Because the law of value dominates not only on the home front of class exploitation, but also in the world market where big capital of the most technologically advanced land rules, the theory of state-capitalism was not confined to the Russian Question, as was the case when the nomenclature was used by others.”

Whilst later theoreticians such as Tony Cliff, turned to the writings of Bukharin on imperialism and state-capitalism, adopting his linear analysis of the continuous development from competitive capitalism to state capitalism, Dunayevskaya explicitly rejected such an approach:

“The State-capitalism at issue is not the one theoretically envisaged by Karl Marx in 1867-1883 as the logical conclusion to the development of English competitive capitalism. It is true that “the law of motion” of capitalist society was discerned and profoundly analysed by Marx. Of necessity, however, the actual results of the projected ultimate development of concentration and centralization of capital differed sweepingly from the abstract concept of the centralization of capital “in the hands of a single capitalist or in those of one single corporation”. Where Marx’s own study cannot substitute for an analysis of existing state-capitalism, the debates around the question by his adherents can hardly do so, even where these have been updated to the end of the 1920’s”

Dunayevskaya went so far as to argue that to turn to these disputes other than for “methodological purposes” was altogether futile; and it is with regard to the dialectical method that Dunayevskaya stands apart from other approaches to this question. The state-capitalism in question is not just a continuous development of capitalism but the development of capitalism through the transformation into opposite. In the Marxian concept of history as that of class struggles, there is no greater clash of opposites than “the presence of the working class and the capitalist class within the same modern society”. This society of free competition had developed into the monopoly capitalism and imperialism analysed by Lenin in 1915, simultaneously transforming a section of the working class itself and calling forth new forces of revolt, making the Russian Revolution a reality. The state-capitalism Dunayevskaya faced emerged as the counter-revolution, which grew from within that revolution, gained pace. With the onset of the Great Depression following the 1929 crash, argued Dunayevskaya the “whole world of private capitalism had collapsed”:

“The Depression had so undermined the foundations of “private enterprise”, thrown so many millions into the unemployed army, that workers, employed and unemployed, threatened the very existence of capitalism. Capitalism, as it had existed – anarchic, competitive, exploitative, and a failure – had to give way to state planning to save itself from proletarian revolution”.

This state ownership and state planning was not a “war measure”, but rapidly emerged across the industrially advanced and the underdeveloped countries. State intervention characterised both Hitler’s Germany, with its Three Year Plans, as a prelude to a war to centralize all European capital, and the USA where Roosevelt launched his ‘New Deal’. This tendency did not decline after the war but accelerated such as under the Labour Government in Britain. Dunayevskaya argued that the “true index of the present stage of capitalism is the role of the State in the economy. War or peace, the State does not diminish monopolies and trusts, nor does it diminish its own interference. Rather, it develops, hothouse fashion, that characteristic mode of behaviour of capitalism: centralization of capital, on the one hand, and socialization of labour on the other.”

This was a world-wide phenomenon and whilst it was true that Russian state-capitalism, “wasn’t like the American, and the American New Deal wasn’t like the British Labour Party type of capital, nor the British like the German Nazi autarchic structure”. It found expression not only in the countries subjugated by Russian imperialism in Eastern Europe and in Communist China but also in the newly independent states following the anti-colonial revolutions.

Despite the varied extent of state control over sectors of these economies taken as whole all revealed we had entered a new epoch in history, differing from the period of Lenin’s analyses, as his was from that of Marx’s own lifetime. What Marx had posed in theory of the centralization of capital “into the hands of a single capitalist or a single capitalist corporation” had become the concrete of the new epoch.

While references to State Capitalism began in an attempt to define the post revolution Russia, and later in response to the rise of Fascism and the American New Deal, what was overlooked by traditional political Marxists was that State Capitalism was not just a feature of a particular kind of Capitalism but was a historic shift in capitalism. It was a shift that Left Wing Communists identified as the period of decline of capitalism, rather than its ascendency. A period of capitalist decadence. During the boom times of the fifties, sixties this seemed to be an outrageous assumption. Capitalism was booming, wages were increasing, a consumer society was being created that the world had never seen before. And yet by 1968 that was all to fall apart as the world under went a revolution not seen since 1919. And while that revolution failed to challenge capitalism it showed that it was rotten to the core.

The Seventies and on saw capitalism lurch from crisis to crisis, starting with the Oil Crisis of 1974. Massive inflation, wage and price controls, the decline of the world economy ending in the Wall Street crash of 1984. Truly those who said that capitalism was in a period of decadance were now having the last laugh.

State capitalism

On the economic level this tendency towards state capitalism, though never fully realised, is expressed by the state taking over the key points of the productive apparatus. This does not mean the disappearance of the law of value, or competition, or the anarchy of production, which are the fundamental characteristics of the capitalist economy. These characteristics continue to apply on a world scale where the laws of the market still reign and still determine the conditions of production within each national economy however statified it may be. If the laws of value and of competition seem to be ‘violated’, it is only so that they may have a more powerful effect on a global scale. If the anarchy of production seems to subside in the face of state planning, it reappears more brutally on a world scale, particularly during the acute crises of the system which state capitalism is incapable of preventing. Far from representing a ‘rationalisation’ of capitalism, state capitalism is nothing but an expression of its decay.

The statification of capital takes place either in a gradual manner through the fusion of ‘private’ and state capital as is generally the case in the most developed countries, or through sudden leaps in the form of massive and total nationalisations, in general in places where private capital is at its weakest.

In practice, although the tendency towards state capitalism manifests itself in all countries in the world, it is more rapid and more obvious when and where the effects of decadence make themselves felt in the most brutal manner; historically during periods of open crisis or of war, geographically in the weakest economies. But state capitalism is not a specific phenomenon of backward countries. On the contrary, although the degree of formal state control is often higher in the backward capitals, the state’s real control over economic life is generally much more effective in the more developed countries owing to the high level of capital concentration in these nations.

On the political and social level, whether in its most extreme totalitarian forms such as fascism or Stalinism or in forms which hide behind the mask of democracy, the tendency towards state capitalism expresses itself in the increasingly powerful, omnipresent, and systematic control over the whole of social life exerted by the state apparatus, and in particular the executive. On a much greater scale than in the decadence of Rome or feudalism, the state under decadent capitalism has become a monstrous, cold, impersonal machine which has devoured the very substance of civil society.

The epoch of State Capitalism as the historical reflection of the decline of capitalsim, its decadence, continues to this day. Called many things, globalization, post-fordism, post-modernism, it is all the same, the decline of capitalism. Global warming, the gap between rich and poor, nations and peoples, shows that capitalisms rapid post war expansion has reached its apogee and is now desperately scrambling to run on the spot.

Despite the so called neo-liberal restoration of the Reagan,Thatcher era. They simply reveresed the Keynesian model, by using the state not to prime the pump through social programs or public services but through tax cuts and increasing militarization/military spending. In fact one of the often overlooked aspects of the success of post WWII Keynesianism was what Michael Kidron called the Permanent War Economy.

Corporatism is the capitalist economy of the U.S. Empire, as seen in its continual permanent war economy that has existed since the end of WWII and continued with wars and occupations to enforce its Imperial hegemony across the globe. America is Friendly Fascism.

The Explosion of Debt and Speculation

Government spending on physical and human infrastructure, as Keynes pointed out can also fuel the economy: the interstate highway system, for instance, bolstered the economy directly by creating jobs and indirectly by making production and sales more efficient. However, spending on the military has a special stimulating effect. As Harry Magdoff put it,

A sustainable expanding market economy needs active investment as well as plenty of consumer demand. Now the beauty part of militarism for the vested interests is that it stimulates and supports investment in capital goods as well as research and development of products to create new industries. Military orders made significant and sometimes decisive difference in the shipbuilding, machine tools and other machinery industries, communication equipment, and much more....The explosion of war material orders gave aid and comfort to the investment goods industries. (As late as 1985, the military bought 66 percent of aircraft manufactures, 93 percent of shipbuilding, and 50 percent of communication equipment.) Spending for the Korean War was a major lever in the rise of Germany and Japan from the rubble. Further boosts to their economies came from U.S. spending abroad for the Vietnamese War. (“A Letter to a Contributor: The Same Old State,” Monthly Review, January, 1998)

The rise of the silicon-based industries and the Internet are two relatively recent examples of how military projects “create new industries.” Additionally, actual warfare such as the U.S. wars against Iraq and Afghanistan (and the supplying of Israel to carry out its most recent war in Lebanon) stimulates the economy by requiring the replacement of equipment that wears out rapidly under battle conditions as well as the spent missiles, bullets, bombs, etc.

To get an idea of how important military expenditures are to the United States economy, let’s look at how they stack up against expenditures for investment purposes. The category gross private investment includes all investment in business structures (factories, stores, power stations, etc.), business equipment and software, and home/apartment construction. This investment creates both current and future growth in the economy as structures and machinery can be used for many years. Also stimulating the economy: people purchasing or renting new residences frequently purchase new appliances and furniture.

During five years just prior to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (through 2000), military expenditures relative to investment were at their lowest point in the last quarter century, but were still equal to approximately one-quarter of gross private investment and one-third of business investment (calculated from National Income and Product Accounts, table 1.1.5). During the last five years, with the wars in full force, there was a significant growth in the military expenditures. The housing boom during the same period meant that official military expenditures for 2001–05 averaged 28 percent of gross private investment—not that different from the previous period. However, when residential construction is omitted, official military expenditures during the last five years were equivalent to 42 percent of gross non-residential private investment.*

The rate of annual increases in consumer expenditures fall somewhat with recessions and rise as the economy recovers—but still increases from year to year. However, the swings in private investment are what drive the business cycle—periods of relatively high growth alternating with periods of very slow or negative growth. In the absence of the enormous military budget, a huge increase in private investment would be needed to keep the economy from falling into a deep recession. Even with the recent sharp increases in the military spending and the growth of private housing construction, the lack of rapid growth in business investment has led to a sluggish economy.

See

State Capitalism

Find blog posts, photos, events and more off-site about:

corporatism, fascism, statecapitalist, statecapitalism, Negri, Rhule, Marx, Russia, US, Kidron, Magdoff, Dunaveskaya, JohnsonForrestttendency, CLRJames, Tronti, Keyenes, keyenesian, ecomonics, decadence, capitalism, fordism, post-fordism, Russianrevolution, 1968, militarism, neo-liberal, Mussolini, Distributism, SocialCredit, WWI, Catholic, communism, socialism