I wrote over a year ago that “doomerism,” or “doomism,” if you prefer, ought to be a precondition for activism. If you believe that the sea won’t soon rise and drown the coastal cities that run the world’s economies, if you believe that deserts won’t swell and swallow up farmlands, if you believe that fascist predatory schemes don’t threaten to spill over into genocide and nuclear war then you have most likely consumed the opiate of happy endings. You capitulate to the cult of false hope, and go about your life in the habitual assumption that good fortune will intervene, as it always has. Trump will die as Hitler did, and after a brief ritual of reckoning, a few therapeutic hangings perhaps, we can all return to the daydreams of a brighter future, or, minimally, the consolation that life goes on. Politics shapes itself to fit the contours of our national stories, our tales, our self-deception, our faith in a mystically blessed USA – the beneficiary of an eternal sequence of eleventh hours.

Maybe we have crossed a threshold into a set of contingencies that no longer adheres, even remotely, to the plotline of our accustomed narrative. Perhaps we have entered a new moral dimension where human regrets no longer have access to the brakes of corporate bureaucracy. What happens to our communities, towns, cities, nations and farmlands if the sixth extinction leapfrogs from being a hypothetical construct to an encroaching reality, with drowned coastal cities, epic wildfires, unimaginable hurricanes and blizzards, desertified croplands and empty shelves at the grocery store? I believe that many of us expect that nature will offer humanity some last minute gift of clarity, as if an anthropomorphic environment itself will create a “Goldilocks Zone” for activism in which pain, anger and resolve all attain “critical mass.” But the US has always been a land of lies, myths, false history and, above all else, manufactured optimism.

We, who call ourselves progressive, grudgingly have begun to admit that we live within a consolidating fascist nightmare, but our collective mindset has been washed and rewashed in the toxic bromides of national destiny. The US survived two centuries of slavery, decades of Jim Crow, the fascist aspirations of Father Coughlin, Joe McCarthy and Richard Nixon, and for every assault we have formulated a counterattack. We have John Brown, MLK, Muhammed Ali, even Bernie Sanders, and so many warriors of free speech and opposition – Ralph Nader, Dick Gregory, Woody Guthrie and let’s toss in Jesse Welles to keep ourselves current. We are drunk on the nostalgic elixir of The New Deal and Keynesian economics. We, the putative beacon of global Democracy have absorbed the mythology of temporary setbacks.

Unfortunately, we no longer deal exclusively with the bumps and bruises of an eternally rapacious US right wing that has never abandoned its Confederate roots. The right that currently flourishes in the US does not merely bathe in wistful memories of slavery and Jim Crow – it has fully merged with capitalism, circling the wagons to fend off the threat of climate activism via a government takeover, conceived, funded and carried out with oil industry “dark money” and Heritage Foundation planning. The Republican juggernaut has unified around a platform of war and oil colonialism (hiding behind a smokescreen of immigrant scapegoating). The fossil fuel empire no longer limits itself to the rhetoric of denial, but expansively wages an all-out war against nature with the spoils of its successful coup – a $1.5 trillion dollars of imperial military force. Consider the following quote:

“A US foundation associated with the oil company Shell has donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to religious right and conservative organizations, many of which deny that climate change is a crisis, tax records reveal.

Fourteen of those groups are on the advisory board of Project 2025, a conservative blueprint proposing radical changes to the federal government, including severely limiting the Environment Protection Agency.

Shell USA Company Foundation sent $544,010 between 2013 and 2022 to organizations that broadly share an agenda of building conservative power, including advocating against LGBTQ+ rights, restricting access to abortions, creating school lesson plans that downplay climate change and drafting a suite of policies aimed at overhauling the federal government.”

The rightwing elites, busily consolidating their particular type of all-American fascism, have seldom been recognized in mainstream media stories as being an extension of the fossil fuel industry. Some pundits may lament that “drill, baby drill,” became the rallying cry of the last Trump campaign, but how often does the press rigorously follow the cash binding Trump to Exxon-Mobil and Chevron?

The clues are everywhere in plain sight. Recall that Trump offered to rescind most environmental regulations in exchange for a billion dollars in fossil fuel campaign donations. This represents a quid pro quo so transparently unethical that, in any other time period, could have only been finalized in absolute secrecy. The marriage of politicians and oil has been performed with bells and whistles, but the relationship still manages to fly under the radar. In the 2024 election Kamala “I Love Fracking Too” Harris made no mention of Trump’s campaign dependence on fossil fuel money.

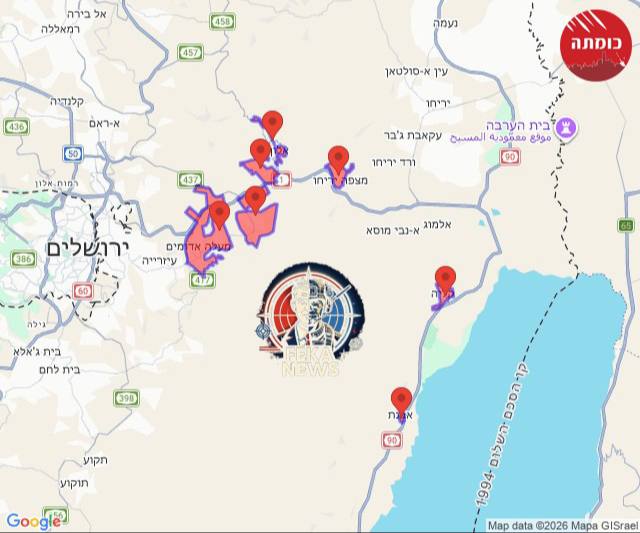

The two nations being the most obvious targets of US imperial design are Venezuela and Iran (rumored to be under imminent threat of US bombing attacks as I write) – two of the most prolific oil producing nations in the world. The proposed annexation of Canada would bring another oil rich land into the fold of US domination. We might also view Trump’s attempts at a rapprochement with Putin’s Russia as an effort to gain access to Russian oil extraction. The absurdity of our times pivots around a fossil fuel industry contrivance –Kakistocratic Fascism – racing toward consolidation neck and neck with global extinction. We can’t fight the power if we don’t grasp the plot.

This is catastrophic news for planet earth – we have already entered an era of environmental danger unprecedented in human history and quite likely never encountered in geological history either. The greatest environmental apocalypse in the evolution of planet earth took place some 252 million years ago at the Permian/Triassic boundary. Geologists believe that a “large Igneous Province” (LIP) is the smoking gun for the Permian/Triassic extinction event. Some two million years of hyper-volcanism subjected the flourishing biosphere to both a prolonged buildup of atmospheric CO2 from volcanic “outgassing” and from concomitant carbon emissions as coal fields ignited by flowing lava burned for thousands of years. The Permian “Great Dying,” that eliminated some 90% of species, came perilously close to sterilizing the entire planet. Ocean temperatures reached levels resembling those of a hot tub. Acidification, bleached coral reefs and deep ocean anoxic environments – foul smelling, sulfuric and lifeless – characterized the preeminent biological catastrophe in the half billion years of multicellular evolution.

The Permian offers us an imperfect window into our own fossil fuel narrative. The noted paleontologist, Gerta Keller, has called fossil fuel burning, and the natural-historical trend of volcanically driven mass extinction, “exactly the same.” Researchers believe that the Permian extinction – although involving hundreds of thousands of years of volcanic activity – can largely be traced to relatively short periods (lasting a few thousand years) of volcanic pulses. These brief events released highly concentrated amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere. CO2 ppm spiked to over five times the levels that preceded the Siberian Traps volcanism. At its most intense, scientists, using proxy sedimentary samples, have estimated that the Siberian Traps and the proximate flaming coal deposits released 4.5 gigatons of CO2 into the atmosphere every year (1 gigaton equals a billion tons). How, you might ask does that compare with Exxon-Mobil/Chevron’s etc. cumulative yearly emissions? In 2024 atmospheric carbon increased by 38 gigatons – roughly 8 times faster than at the apex of the Permian. If current trends continue, we should expect CO2 emissions to reach 75 gigatons annually by 2050 – or 18 times the velocity of atmospheric carbon during the worst volcanic pulses of the end Permian extinction. Allow that to sink in. The mass exterminating event of our times does not involve the callous indifference of continental plates poking holes in the lithosphere – the lethal chain of events involves a century of oil industry control of government policies on a global scale, culminating in a fascist coup carried out by proxies of the fossil fuel industry – notably, Donald Trump.

Experts warn us that preindustrial CO2 atmospheric concentrations may increase by a factor of three in the next 75 years. This is not compatible with human civilization. One should also understand that CO2 is not the only greenhouse gas. As the earth heats, deadly amounts of Methane are released from melting permafrost and warming oceans. Nitrous Oxide is added to the atmosphere from human agricultural practices, and a number of industrial pollutants cause additional warming. Water vapor is also a greenhouse gas, and as the atmosphere warms, water vapor increases in a feedback loop.

It has been like pulling teeth to get media figures to realize that Trump is a fascist, but that realization only comprises half of the story – Trump is merely an avatar for oil profits. The oil industry drives US fascism with limitless cash and a stream of industrially created right wing narrative fictions from well endowed think tanks. We may vaguely understand that climate deterioration causes immigration to increase, while those too poor to immigrate suffer and die, but we must also be aware that the oil industry funds the politicians, media and think tanks that shape toxic immigration narratives. The evil irony takes your breath away. Those in the Global South, who lose their lives and livelihoods to oil industry greed, also double as scapegoats.

The oil industry has written stories that point fingers at their victims in the past – I am forced again to tell the story of tetraethyl leaded gasoline – the weapon employed to commit the worst crime in history. Leaded gasoline caused a hundred million premature deaths, and the lead poisoned brains of inner-city children has, according to many researchers, been the most likely reason for the several decades of increased violent crime in US cities during the 1960’s to the late 1990’s. The banning of tetraethyl (beginning incrementally in 1970) brought the crime rates down. The dominant US political narrative employed by Nixon, Reagan and Clinton, blamed spiking crime rates on super-predators (a euphemism for Black youth) who were fed into the burgeoning “prison industrial complex.”

History may not repeat itself, but “history just rhymes” we have been warned. Once again the oil industry and its political proxies have composed a narrative to blame their own horrific crimes on innocent scapegoats. Immigrants are being brought by the tens of thousands into brutal caged settings while the perpetrators of a looming planetary holocaust evade all consequences. We struggle to tell the story accurately – the legendary Climate activist, Roger Hallam pleads for us to use requisite language:

“There are certain words polite society forbids.

Genocide.

Collapse.

Treason.

Say them, and you are hysterical. Extreme. Nuts.

But there comes a point in the life of a civilisation when refusing to use the correct word becomes the real extremism.

We are living through the greatest act of intergenerational violence in human history. The evidence is no longer scattered across obscure journals. It is in mainstream newspapers. Intelligence briefings. Government admissions.

The question is no longer whether the crisis is real. The question is whether we are prepared to describe what is happening with moral clarity.”

In line with Hallam’s exhortation to embrace “moral clarity,” we must understand the narrative predicament that we now suffer. A fascist coup, with no other specific description is terrible enough, but a fascist coup paid for and overseen by the fossil fuel industry aspires to do more than merely kill people and scarf up profits. The US environmental program ought to be seen as The Siberian Traps Large Igneous Province on steroids. The barest possibility of survival depends on regime change and the nationalization of the oil industry. Trump and his senile antics are a mere distraction while the oil industry raises its dagger.

Fossil fuels are the mother of capitalism – AI and tech industries consume vast quantities of oil – they are fossil fuel adjuncts. The US Military is the largest institutional consumer of fossil fuels on earth, but we must understand, as political writer, Grace Blakeley, observes, that the military is inexorably bound to fossil fuels in the manner of a composite entity. The military does not merely consume fossil fuels and pollute the dying planet, it fights wars to procure these fuels. Think of the oil/military industrial complex as the mother of death, the author of US fascism and the executioner of planet earth – then act accordingly.

Phil Wilson writes at Nobody’s Voice.Email

.png)

.png)