The logic of ‘Capital’, the Systematic Dialectic School and a defence of the logical-historical method

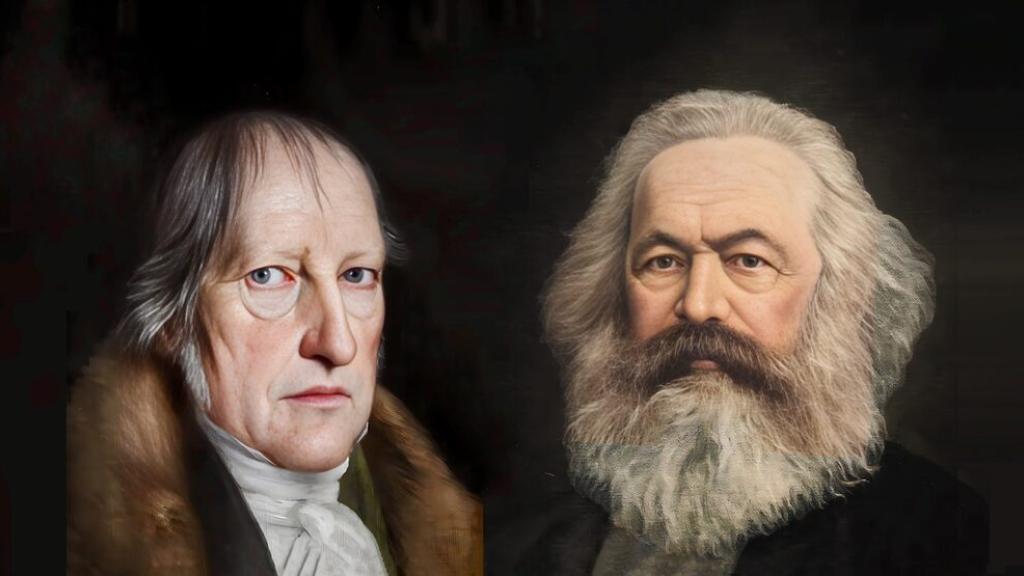

In the past three decades, the Systematic Dialectic School has challenged the traditional logical-historical description of Karl Marx’s method. Inspired by the Standard Critique (SC)1 of Marx’s Transformation Procedure (TP), they insist Marx’s Capital can best be understood as mirroring Hegel’s Logic, in both its form and content.

Andy Blunden is a Marxist philosopher perhaps best known for his work curating Marxists.org. This article takes Blunden’s books, The ‘Capital’/‘Logic’ Debate and Marx's Capital – Hegelian Sources, as a jumping off point for a re-examination of the relationship of Hegel’s Logic to Marx’s Capital in general, and of the Systematic Dialect school in particular. The background of the TP debate haunts Blunden’s books but is not directly addressed by them; they are included here, nonetheless, as they are directly relevant to the claimed Hegelian and Marxist foundations of the Systematic Dialectic School.

Hegel’s objective and subjective logic

Hegel defined logic “as the science of pure thought”, which had overcome “the opposition of consciousness between a being subjectively existing for itself, and another but objectively existing such being” (Hegel, p40). In the pure concept, the subject was identical with being (the pure object) and vice versa as “cognition transforms the objective world into concepts,” and in the process “finds propositions and laws and proves their necessity” (Hegel, p707). Consequently, as the first division of logic must be “between the logic of the concept as being and of the concept as concept” or “objective and subjective logic” (Hegel, p40), so Volume One of Hegel’s Logic is “The Objective Logic”, which is in turn divided into two parts (Being and Essence) and Volume Two, “The Subjective Logic”, in one part (the Concept).

For Hegel, a Monist, Deist and Idealist, the objective logic of nature, or the universe, revealed God’s thought as the Absolute Idea: “God as living God, and better still as absolute spirit, is only recognized in what he does” (Hegel, p626). As God is logical so the expression of God’s thought in the objective universe created by him must be logical too, so inasmuch as “reason, is in the objective world, that spirit and nature have universal laws to which their life and their changes conform”. Hence, insofar as concepts accurately represented the universe, so “the determinations of thought have objective value and concrete existence” (Hegel, p30).

Through discovering the logic of objective reality, people could know God; the “concrete existing world” is raised to “a kingdom of laws” (Hegel, p444). Thought, or more specifically logic or conceptual thought, “is to be understood as the system of pure reason, as the realm of pure thought. This realm is truth unveiled, truth as it is in and for itself,” its “content is the exposition of God as he is in his eternal essence before the creation of nature and of a finite spirit” (Hegel, p29). Hegel thus incorporated Spinozism “within as its subordinate”, (Hegel, p512) “acknowledging its standpoint as essential and necessary” (Hegel, p513), while nonetheless asserting that the Absolute Idea expressed in knowledge provided the moment of “explicit and concrete idealism, lacking in Spinoza” (Hegel, p130). God could be known through the universe that he created.

Subjective logic provided the conceptual tools through which people could understand the essential nature of objective reality: “when we speak of things, we call their nature or essence their concept, and this concept is only for thought” (Hegel, p16). Truth was the extent to which concepts (the subject) accorded with the object: “the objectivity of thought is here, therefore, specifically defined: it is an identity of concept and thing which is the truth” (Hegel, p521). Thoughts, when true, expressed the essence of the thing or its “concrete existence; it is not distinct from its concrete existence” (Hegel, p422).

The essential nature of the thing was an objective property of it, “this determinateness of the thing-in-itself is the property of the thing,” (Hegel, p426) and defined its existence, “the concrete existence is the thinghood with its properties and matters” (Hegel, p441), providing “a principle of concrete existence saying that whatever is, exists concretely” (Hegel, p420). Hegel’s subjective logic, or the Concept, provides a method to interrogate, understand and reveal the objective logic of the universe, the nature of Being as determined by its Essential laws.

Truth is the extent that the concept accords with the essence of the object. The test of truth is not subjective but objective, the extent to which concepts accord with concrete reality. Subjective logic whenever it “is taken as the science of thinking in general … constitutes the mere form of a cognition; that logic abstracts from all content”. The objective content or matter of logic “must be given from elsewhere.” This “matter does not in the least depend on it,” so the application of logic is “only the formal conditions of genuine knowledge, but does not itself contain real truth”. Therefore, “logic is only the pathway to real knowledge, for the essential component of truth, the content, lies outside it” (Hegel, p24).

The distinction between objective thought — the universal laws that govern nature (God’s thought) — and subjective thought — what people do to discover the universal laws that govern nature — is a key distinction. It is also the cause of much misunderstanding of Hegel’s Logic, which nonetheless, attempts to provide a logically consistent explanation of objective and subjective logic across its two volumes, which therefore cannot be meaningfully separated. The objective logic of the universe and the subjective logic of humans discovering that objective logic is one whole.

Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason questioned how a logical antipode or antonym, notably Being and Nothing, could logically exist when the existence of one pole contradicts the existence of the other. The existence of Absolute Nothing is a contradiction in terms both for Being and Nothing — if nothing exists, it is not nothing; if nothing exists, it is not being. Hegel overcame this contradiction through noting that neither Absolute Being and Absolute Nothing really existed, and so they were the same: “Being, the indeterminate immediate is in fact nothing, and neither more nor less than nothing”; (Hegel, p59) rather these logical poles were conceptual abstractions that sublate, incorporate or express all of the essential features of Being and Nothing in them.

Concrete reality moved in a constant contradictory flux of Becoming between them, such that these conceptual poles “both cease to be abstractions by receiving a determinate content; being is then reality” (Hegel, p64). Their truth was not the poles but the contradictory movement between them Becoming, which is the essential logical innovation that defines Hegel’s system, “their truth is therefore this movement of the immediate vanishing of the one into the other: becoming” (Hegel, p60). In “essence, therefore, the becoming, the reflective movement of essence, is the movement from nothing to nothing and thereby back to itself” (Hegel, p346).

This movement between its poles was necessarily contradictory. As logic (the laws of thought) takes its content from that objective reality, so it must express this contradictory movement: “the firm principle that formal thinking lays down for itself here is that contradiction cannot be thought. But in fact the thought of contradiction is the essential moment of the concept” (Hegel, p745). The contradictory movement of the universe must be expressed in the concept, in contrast to the formal, but artificial and so fictional consistency of formal logic.2 These concepts are not counterfactuals, events that may have occurred if things had turned out differently, but the conscious conceptual expression of an objects’ “logical nature” (Hegel 18). Every really existing determinate thing is therefore, a unity of opposites, a contradiction moving between its two poles of Being or Nothing — it is Becoming, the necessary essence of real concrete existence.

Paradoxically, as Absolute Being and Absolute Nothing do not exist, except as abstractions, neither does the Absolute Idea or God: “God as the pure reality in all realities, or as the sum-total of all realities, is the same empty absolute, void of determination and content, in which all is one” (Hegel, p86), as “existence is determinate being” (Hegel, p83) and God is indeterminate, so God does not exist. As Frederick Engels pithily remarked, Hegel’s absolute idea was “only absolute insofar as he has absolutely nothing to say about it” (Engels) and could thus be discarded, as the materialist dialectic of Marx and Engels supplanted Hegel’s idealist one. Hence, the test of the truth of Marx’s Capital and whether it actually describes the essential laws that determine capitalism’s contradictory development is not the use of Hegel’s Logic, but capitalism, which lies “outside it”.3

Given that Marx acknowledged his debt to Hegel, and the use of Hegel’s Logic does not determine the truth of objective laws, simply pointing out, reaffirming or discovering that Marx did in fact use the method he said he used is not really discovering anything at all. Furthermore, as the use of a form of avowedly dialectical logic is no guarantee of truth according to Hegel’s Logic itself, the reader is forced to ask why the debate?

The debate in fact arises as the vast bulk of political economists from the Marxist tradition accept the standard, formal logical, mathematical critique of Marx’s value theory. The SC rests on two components. The first negative part is von Bortkiewicz’s mathematical critique of Marx’s TP, which showed that it violated the laws of linear algebra and so, as maths is elided with logic,4 Marx's value theory is deemed to be contradictory and logically inconsistent. The second positive part was Piero Sraffa’s claim that prices and profits could be derived physically from the structure of production itself without value, which was as a result (more or less) redundant.5

This shocking discovery produced two alternative responses from Marxists who accepted the SC while wanting to save Marx from Sraffa. First, the numerous attempts to find a mathematical solution to the transformation problem — an impossibility on the basis of maths. Second, to interpret it away — by finding some other “reading” of Marx’s value theory that avoids or evades the problems attributed to it in the SC, notably to, in some way, rid Marx’s value theory of the TP or assume it away. The advocacy of “Systematic” dialectics to Marx’s Capital is a variety of the latter. It claims the truth of Marx’s Capital rests not on its objective analysis of capitalism, but its subjective fealty to Hegel’s Logic, and reflects the influence of the so-called New Solution to the TP.

New Solution theorists, such as Duncan Foley, Gérard Dumenil, Dominique Levy, Ben Fine and Geert Reuten, claim Marx had “forgotten” to transform the input values of his TP in Capital III. If these values were assumed to be transformed (if the capitalist commodity was assumed from the beginning of Capital, so that there were no values), then there was nothing to transform, and so there was no transformation problem. This underpins their insistence, following David Ricardo (but expressly rejected by Marx), that Capital must begin with the particular, capitalist commodity, not the universal, simple commodity.

The logical arc of Capital

Blunden claims that “no one explained satisfactorily” how “Logic describes objective social processes such as exhibited by value” (Blunden, p117). In fact, as Blunden points out, Marx’s introduction to the Grundrisse explains the application of this method at length. Reuten attempts to paraphrase Marx’s introduction in his explanation of the Systematic Dialectic method,

In general, a systematic-dialectical presentation (Darstellung) can be characterised as a movement from an abstract-universal starting point to the concrete-empirical, gradually concretising the starting point in successive stages, thus ultimately aiming to grasp the empirical phenomena in their systemic interconnectedness. (Reuten, p65)

This approach has very little to do with Hegel’s notion of Becoming as the unity of opposites, the unresolved and unresolvable conflict of irreconcilable antimonies. It is probably closer to a kind of empiricist positivism or Popperian successive approximation, with a kind of linear advance ultimately arriving at an approximation of “truth”. It may explain why Reuten and Christopher J Arthur so vehemently reject Marx’s logical starting point of simple or universal commodity production and his end point of banking capital, the irrational but simple or singular of profit without commodity production. Instead, Reuten claims that “Marx’s Capital is an investigation of the characteristic form of the capitalist mode of production” (Reuten, p69). But this is definitely not what Capital is.

Rather Capital traces the essential laws of commodity production and, in its universal form, that of capitalist commodity production. The simplifying assumption of Capital I and Capital II that values equal prices is not the characteristic form of the capitalist mode of production at all (quite the opposite with the transition to the capitalist commodity and profit rates in proportion to capital advanced, meaning values never equal prices at the level of the individual commodity and only imperfectly at the aggregate). Rather, it is an abstraction necessary to demonstrate those essential laws, foremost that social labour is the necessary source of all value, price and profit.

Blunden notes that Systematic Dialectic theorists claim Capital mirrors one of the books of Logic, although they cannot agree which one. Tony Smith, via Arash Abazari, stresses its affinity to the Logic of Essence, Chris Arthur to the Logic of Being, and Fred Moseley to the Conceptual Logic. Thus, they all miss the essential point that Being, Essence and Concept apply simultaneously throughout every chapter of all of these books. Uchida, on the other hand, maps Being, Essence and Concept to different chapters of the Grundrisse, even while Capital as a whole traced a syllogistic arc, but not the one identified by Uchida.

Moseley emphasises Marx’s 1858 note that describes just this arc from “Universality; Emergence of capital out of money, capital and labour, elements of capital” to “Particularity; Accumulation, competition and concentration” to “Singularity; Capital as credit, stock market and money market” (Blunden, p135). Uchida asserts that “Marx’s task in the Grundrisse therefore consists in demonstrating that the genesis of value and its development into capital are described in the Logic” (Blunden, p10). But the Logic did not describe the development of capital.

The Logic provides a method for discovering the conceptual truth of the object — any and all objects. Logical concepts, including Hegelian ones, are empty before their application to the object. Logic, when abstracted from content, is “isolated and imperfect” and so “void of truth” (Hegel, p532). Blunden notes that Uchida’s headings “does not match the location in Hegel’s Logic” (Blunden, p11) but accepts that there are “plausible links” to what he calls the first two moments of the Concept, Universality (U) and Particularity (P), but not Singularity (S), or U-P-S. There is nothing specifically Hegelian about the U-P-S syllogism. Hegel’s contribution was rather to demonstrate the “indeterminate, an infinite manifoldness” of these determinations. Any single syllogism is contingent and “these syllogisms that concern the same subject must also run into contradiction” (Hegel, p593).

Uchida considers that the Introduction to Grundrisse is the Concept, Money is Being and Capital is Essence. The introduction, insofar as it is an explanation of method unrelated to the object, may be an example of subjective conceptual logic. But once it is applied to Money and Capital, it combines Being, Essence and Concept — objective and subjective logic — to form an “adequate concept” which “is something higher; it properly denotes the agreement of the concept with reality, and this is not the concept as such but the idea” (Hegel, p542). Blunden concludes that although Uchida’s argument has “merit”, “his efforts to pin the development of Marx’s argument to Hegel’s Logic is “utterly confused” (Blunden 19).

The simple beginning: Simple commodity production/circulation and “capital in general”

The claim that Marx begins Capital with the capitalist commodity rests on an interpretation of Marx’s category of “capital in general”. Michael Heinrich (1989) states that Marx first uses the concept in the Grundrisse. Heinrich quotes Marx,

Capital, so far as we consider it here, as a relationship of value and money, which must be distinguished, is capital in general, i.e. the quintessence of the characteristics which distinguish value as capital from value as simple value or money (Marx, 1857, Vol .28, p. 236).

Marx is unambiguous: value as capital is distinguished from value as simple value or money, which precede it logically and historically. Heinrich interprets Marx’s sentence to mean “that is, ‘capital in general’ ought to embrace those characteristics which have to be added to value in order for it to become capital”, ignoring Marx’s essential point that capital (self-reproducing value) is distinguished from simple value or simple money. Marx repeats these points in a letter to Engels, Plans for ‘Capital’, in 1858:

Simple money circulation does not contain the principle of self-reproduction within itself and therefore points beyond itself. Money, as the development of its determinations shows, contains within itself the demand for value which will enter into circulation, maintain itself during circulation and at the same time establish circulation–that is, for capital. This transition historical also.

Capital begins and ends with money, but money does not begin and end with capital.6 Simple value or money are distinguished from capital but, nonetheless, necessarily imply its development; they are transformed into capital through a logical and historical process. Capital in general is used in the letter as a broad part consisting of different sections: “Capital contains four sections: A. Capital in general (this is the material of the first part)”. Marx concludes his letter with the complaint,

we now come, namely, to (3) Capital. This is really the most important part of the first section, about which I most need your opinion. But I cannot go on writing to-day. This filthy jaundice makes it difficult for me to hold my pen and bending my head over the paper makes me giddy.

Capital is the third section of the first part of “Capital in General”, following the commodity and money or simple circulation. Marx reiterates the point in the 1859 Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, “the first part of the first book, dealing with Capital, comprises the following chapters: 1. The commodity, 2. Money or simple circulation; 3. Capital in general.” The first part of the book dealing with capital does not start with capital, but the simple commodity, then money (the converted form of the simple commodity or simple circulation) and, only then, capital in general (the converted form of money).

Competition is introduced only after the capitalist commodity, as it modifies values into prices of production by equalising profit rates in proportion to the amount of capital advanced. Heinrich, in asserting that an analysis of capitalism should start with capital rather than the commodity, is essentially repeating Ricardo’s mistake. If values are elided with modified values, then the prima facie contradiction of capitalist commodity production is assumed away, as the redistribution of value to equalise profit rates obliterates the source of value in social labour and profit in surplus value. The logical arc that defines the three volumes of Capital is at one pole, Being (the universal, simple commodity circulation, commodity production without capital), through Becoming (the particular, capitalist commodity production, commodity production with profit) to the other pole, Nothing (the singular, interest bearing capital, and irrational profit without commodity production).

Adam Smith was unable to explain how the basis of the law of value of equivalent exchange (that commodities are exchanged for the amount of socially necessary labour required for their production) continued to determine the value of commodities once the producers were separated from the ownership of the means of production; that is, after, in other words, the primary “rude” state (simple commodity production) had given way to capitalism. Ricardo pointed out that as value cannot arise in circulation, what is a loss for one is a profit for the other to the same amount but in the opposite direction — it makes no difference to the total of value if that value is redistributed from the producers to the capitalists, landlords and banks.

Blunden states that “Marx says the law of value is transhistorical” (Blunden 2025b, p80), presumably as in transcendent beyond and outside of history. But Marx states the opposite: the law of value is historical, “the values of commodities not only theoretically but also historically prius to the price of production. This applies to conditions in which the labourer owns the means of production” (Blunden 2025b, p80). The law of value, as a law of equivalent exchange, is logically and historically prior to capitalist production. This forms his starting point, for as Marx noted,

the phenomenon is very simple as soon as the relationship of surplus-value and profit as well as the equalisation of profit in a general rate of profit is understood. If, however, it is to be explained directly from the law of value without any intermediate link…. no solution of the matter is possible here, only a sophistic explaining away of the difficulty, that is, only scholasticism. (Marx 1861-63)

Under capitalism, values are no longer directly represented in individual prices but only indirectly so. The law of value no longer determines equivalent exchange (as capitalist commodity exchange is not equivalent) but as a law acts as a controlling principle that determines the essential nature of capitalist production, now only indirectly.

The value of the capitalist commodity originates in production, but the transformation of values into prices of production (to equalise profit rates among capitalists in proportion to the amount of capital they advanced) obliterates the origin of profit in productive labour. The law of value of equivalent commodity exchange (that different incommensurate use values are voluntarily exchanged according to the amount of socially necessary labour time necessary for their production) undergoes a logical and historical modification with the transition from simple to capitalist commodity production. Nonetheless, Marx writes,

It is clear that, however much the cost-price of an individual commodity may diverge from its value, it is determined by the value of the total product of the social capital… whether its cost-price is equal to, or greater or smaller than, its value, it can never be produced without its value being produced… those costs of production and those cost-prices are not only determined by the values of the commodities and confirm the law of value instead of contradicting it, but, moreover, that the very existence of costs of production and cost-prices can be comprehended only on the basis of value and its laws, and becomes a meaningless absurdity without that premise. (Marx 1861-63)

Just as (following Ricardo) the redistribution of value between classes from worker to capitalist does not alter its amount, neither does (following Marx) the redistribution of value within classes. Hence the transformation of values into prices of production does not modify the amount of value in aggregate, albeit, as the structure of production changes between simple and capitalist commodity production, there will never be a perfect alignment between the total of value and surplus value within simple commodity production, and the total of value and surplus value of capitalist commodity production. Hence, the disequilibrium implicit in the TP. A disequilibrium which is objective not subjective, and therefore real and not a logical mistake but a requirement of the TP itself — something that must necessarily be included in any model of the transformation of values into prices of production.

Hegel notes that “the universal is in and for itself the first moment of the concept, because it is the simple” (Hegel, p714). Marx’s conceptual abstraction (simple commodity circulation) concentrated all the actual determinants of simple commodity production and exchange within it. The exchange of owner-producers, not capitalist producers, enabled the derivation of the law of value that determined commodity exchange and its essential components (use value, exchange value and value) and, from there, onto the capitalist commodity and surplus value and profit. The starting point was derived from the reflection “all that follows from the first truth must be deduced from it, and the need that this first truth should be something with which one is already acquainted, and even more than just acquainted, something of which one is immediately certain” (Hegel, p53).

Blunden claims that Marx never “did explain why he chose to make a beginning with the commodity and we must examine whether this decision is still appropriate” (Blunden, p186). He also writes that “Volume I of Capital seems to be based on a counterfactual society of independent commodity producers exchanging the products of their labour with each other” (Blunden, p187). But the abstract conceptual poles of the antonym are not counterfactuals: they are not societies that may have occurred if things had been different; they are rather a sublation of the essential determinants of simple commodity production and circulation. The Grundrisse, Marx’s first draft of Capital, began with money, but followed the same conceptual arc as Capital later on. In Theories of Surplus Value (TSV), Marx explained that, although he began with money,

as the converted form of the commodity. What we arrive at is money as the converted form of capital, just as we have perceived that the commodity is the pre-condition and the result of the production process of capital….The formation of interest-bearing capital, its separation from industrial capital, is a necessary product of the development of industrial capital, of the capitalist mode of production itself”. (Marx’s emphasis) (Marx 1861-63)

Arthur asserts that “Marx's development of the capital relation contains no argument of a quasi-causal character purporting to show how capitalism arose” (Arthur, 1998). This is practically the opposite of the truth, as Marx writes,

This determination of value, first indicated by Petty, clearly worked out by Ricardo, is merely the most abstract form of bourgeois wealth. In itself already presupposes: the dissolution of (1) primitive communism (India, etc.); (2) of all undeveloped, pre-bourgeois modes of production not completely dominated by exchange. Although an abstraction, this is an historical abstraction which could only be adopted on the basis of a particular economic development of society. (Marx, 1858)

Marx praised Richard Jones who, although enmeshed in “bourgeois fetishism”, noted that capital rests on the separation of the worker from the ownership of the product. Thus Jones “expresses a correct historical conception of capital”, so that “a solution becomes necessary as soon as the capitalist mode of production is regarded as a determinate historical category”. (Marx 1861-63)

Marx addresses similar arguments opposing the non or trans-historical nature of his critique of capitalism, on very many occasions. But he sums the argument up well here:

Money is indeed not converted into capital as a result of the fact that it is exchanged against the material conditions required for the production of the commodity, and that in the labour process these conditions — materials of labour, instruments of labour and labour — begin to ferment, act on one another, combine with one another, undergo a chemical process and form the commodity like a crystal as a result of this process. The outcome of this would be no capital, no surplus-value. This abstract form of the labour process is common to all modes of production whatever their social form or their particular historical character. The process only becomes a capitalist process, and money is converted into capital only: 1) if commodity production, i.e., the production of products in the form of commodities, becomes the general mode of production; 2) if the commodity (money) is exchanged against labour-power (that is, actually against labour) as a commodity, and consequently if labour is wage-labour; 3) this is the case however only when the objective conditions, that is (considering the production process as a whole), the products, confront labour as independent forces, not as the property of labour but as the property of someone else, and thus in the form of capital. (Marx 1861-63)

Even where Marx begins with money, as in the Grundrisse, this is only the converted form of a commodity. Hence, in the Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Marx starts with the commodity, which is then converted into money, and then money into capital. Marx’s famous opening sentence of Capital explains that “the wealth of those societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails, presents itself as ‘an immense accumulation of commodities,’ its unit being a single commodity. Our investigation must therefore begin with the analysis of a commodity” (in Blunden, p40).

The definition of the commodity as a use value and exchange value is provided by Aristotle. Marx’s analysis of capitalism thus follows a single unfolding principle: the movement of commodity production through its logical arc, from simple commodity production, through capitalism, to the irrational rate of interest expressed in banking capital.

Arthur complains that “it is clear that there is no contradiction involved in the idea of simple circulation at value” (Arthur 1998), and so abandons simple commodity production as the starting point of Capital. Rather, Arthur claims, the existence of free labour is derived from “the concept of capital”, which “demands its prior presence if the dialectic is to proceed.” So, although simple commodity production is not predicated on free labour because the category demands it (according to Arthur), there is free labour in it, even when there is not.

This inverts the relationship between objective and subjective logic. For Arthur the category is not derived from reality; reality is derived from the category. But the contradictions of simple commodity production were real, not conceptual: simple commodity production actually developed into capitalist commodity production; free labour was actually separated from the ownership of the means of production to form capitalist commodity production. This was a historical and logical process that did actually occur.

Arthur has (albeit inadvertently) argued away the material basis of Marx’s analysis of capitalism. If, following Ricardo, capitalist (not simple) commodity production is taken as the starting point for Capital, with alienated labour and equalised profits already assumed from the outset, this is not some innovative or a new solution to the TP but, as Marx observed in the TSV, the “complete” acceptance of “the concept of the capital-fetish” for

economists who, on the one hand, observe the actual phenomena of competition and, on the other hand, do not understand the relationship between the law of value and the law of cost-price, resort to the fiction that capital, not labour, determines the value of commodities or rather that there is no such thing as value. (Marx 1861-63)

If the analysis starts with capitalist commodity production, then the prima facie contradiction in the law of value between equivalent exchange and the equalisation of profit rates (non-equivalent exchange) inevitably leads to the capital fetish — the notion that capital by its mere existence generates profits from nothing. This resolves the problem of the TP by assuming it away, but in so doing obliterates the link between values and prices of production, leading inevitably to the conclusion that “there is no such thing as value”.

Blunden says that Arthur is “at pains to point out that there has never been in history any such things as ‘pure commodity production’” (Blunden, p108). True enough, but there is no pure capitalist production or banking production either. The poles of the antonym are conceptual abstractions, albeit their content is derived from the object, the social reality of simple commodity circulation, capitalism or banking capital. The conceptual abstraction expresses the essential nature of the thing by abstracting from secondary, contingent or only apparent, inessential, forms.

Tony Smith claims that in Capital, “the movement from capital in general ... through many capitals … to bank capital … corresponds to the moments of universality, particularity and singularity examined in the chapter of the Logic titled ‘the Concept’” (Blunden, p93). But Capital starts with universal commodity production (the commodity in general) not capital in general, which is a broader part heading only. The movement through U-P-S not only conforms to the movement in the Concept, but that delineated in both objective and subjective volumes of Hegel’s Logic.

Blunden states: “I believe Marx was mistaken in taking bank capital as the Individual moment, but in any case, it plays a subordinate role in Capital. Smith is correct on the Universal and Particular moments” (Blunden, p93). But banking capital is the individual moment (pure profit production without commodity production) as the polar antithesis to simple commodity production (pure commodity production without profit). At one pole is Absolute commodity production and at the other pole Absolute profit production or “capital par excellence … The complete objectification, inversion and derangement of capital as interest-bearing capital — in which, however, the inner nature of capitalist production, [its] derangement, merely appears in its most palpable form — is capital which yields ‘compound interest’.” (Marx 1861-63)

Reuten begins his Systematic Dialectical explanation of capitalism and the state with capitalist commodity and bifurcation of society (the separation between capitalists and workers) (Blunden, p44). Necessarily, Reuten’s theory of value has nothing to do with “so called socially necessary labour time” (Blunden, p68). Reuten recognises no distinction between value and price. His acceptance of the capital fetish concept means his analysis ignores — indeed denies — the intermediate connections between value and prices, and lacks explanatory power, as “the starting point is … already something which needs explaining and that explanation never comes (Blunden, p49). Blunden notes that Reuten’s “functionalist exposition of the capitalist state is a rationalisation, not a comprehension” (Blunden, p55) and that it contradicts the method of both Hegel’s Logic and Marx’s Capital.

According to Moseley, “Marx’s theory in all three volumes of Capital is about a single system, the actual capitalist economy, which is assumed to be in long run equilibrium” (Blunden, p119). But Capital begins and ends with the conceptual abstractions (simple commodity production and interest-bearing capital), neither in a pure form representative of an actual capitalist economy.

Hegel’s dialectic goes from the “positive to the negative — the absence of the positive” (Hegel, p77). Disequilibrium or non-equilibrium is the negative of equilibrium and implies equilibrium, its opposite or antipode, so the logical argument goes from the simple positive to the negative. To understand disequilibrium, it is necessary to understand equilibrium. Marx assumes capitalism is in equilibrium to prove it is possible at all. This assumption does not mean it is in equilibrium, short or long run. Determinate capitalism, that is actual, real capitalism (in contrast to the conceptual poles) is neither one nor the other, but Becoming, in a movement between them — a combination of both equilibrium (perfectly balanced reproduction) and disequilibrium (no reproduction at all) as contradictory unity of opposites (Hegel, p378).

Conclusion

Marx’s categories in Capital are ordered subjectively according to their objective position within the capitalist system. Although their order is logical (subjective not objective) — the opposite of history (objective not subjective) — it nonetheless traces the development of commodity production through history insofar as history is objectively lawful or logical. This subjective ordering of objective categories is expressed in the sequence of moments determined by that essential nature; that is, simple commodity production, money, wage labour, capital, the division of labour, primitive accumulation of capital, industrial capital, the division between Departments, transformation of values into prices of production, to banking and finance and so on. It is historical-logical, insofar as history is lawful or logical.

Neither pole of the antimony, simple commodity production and interest-bearing capital, are capitalist per se, nor exist in their pure form; rather they are conceptual abstractions. The movement of actual capitalism — a system of generalised or universal commodity exchange for profit — is a ceaseless movement between them and so a prima facie contradiction (simultaneously both equivalent and non-equivalent commodity production): a unity of opposites.

Logic provides the laws of conceptual thought, the subjective means through which humans understand the objective laws of the universe. The conceptual idea is true insofar as it accords with the essence of the concrete object. Logic before its application is empty except insofar as it expresses the laws of thought; it discovers its content through its application.

The poles of the antimony, illustratively Being and Nothing concentrate the essence of the determinant thing but find their truth in Becoming, the concrete existence of the thing in its contradictory movement between the poles that define the limits of its existence, positively and negatively. The movement of the polar concept is syllogistic Universal-Particular-Singular (U-P-S): from simple, positive or universal, to complex, negative or singular.

Hence the logical order of Capital is from simple commodity production, through capitalism, to interest bearing capital — from equilibrium to disequilibrium, etc. The Systematic Dialectical School rejects the starting point of Marx’s Capital in simple commodity production, and so reject value as the foundation of its analysis and, paradoxically, the logical arc upon which it is based.

References

Arthur, Christopher J (1998). “Systematic dialectic”. Science & Society, 62(3), 447-459.

Blunden, Andy (2025). The ‘Capital’/‘Logic’ Debate. Leiden/Boston, Brill.

Blunden, Andy (2025b). Marx's Capital – Hegelian Sources. Leiden/Boston, Brill.

Engels, Frederick (1886) Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1886/ludwig-feuerbach/

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich (2010). The Science of Logic. Translated and edited by George Di Giovanni, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Heinrich, Michael (1989). “Capital in general and the structure of Marx's Capital. New insights from Marx's ‘Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63’.” Capital and Class. https://marxismocritico.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/capital-in-general-heinrich.pdf.

Marx, Karl (1936, 1858). “Plans for ‘Capital’” to Frederick Engels from Selected Correspondence, 1846-1895. International Publishers, New York. https://revolutionsnewsstand.com/2025/01/05/plans-for-capital-1858-by-karl-marx-to-frederick-engels-from-selected-correspondence-1846-1895-international-publishers-new-york-1936/

Marx, Karl (1859), A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1859/critique-pol-economy/

Marx, Karl (1861-3), Theories of Surplus Value, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1863/theories-surplus-value/

Reuten, Geert (2024). Essays on Marx’s Capital; Summaries, Appreciations and Reconstructions. Leiden/Boston Brill.

- 1

This standard critique is a combination of firstly, Ladislaus von Bortkiewicz’s mathematical refutation of Marx’s Transformation Procedure (TP) and secondly, the physical price series of Piero Sraffa, which claims to render value theory redundant by providing a method for the direct physical derivation of prices and profits.

- 2

Hence, von Bortkiewticz’s rediscovery that the movement from values to prices of production is contradictory both mathematically and in reality, and natural and inevitable and therefore true. This contradiction, and its mathematical expression, should not have been a surprise to anyone, least of all Marx who had already noted it in the Grundrisse. Its devastating impact on Marxist versions of Marx’s value theory is a testament to the hegemony of mathematical formal logical modelling in political economy.

- 3

Thanks to George Daremas for his comments on Hegel.

- 4

Hegel had previously commented “the attempt to conduct any such proof on a truly mathematical basis, that is, neither empirically nor conceptually, is an absurd undertaking. Proofs of this kind presuppose their theorems and even the laws to be proved from experience” (Hegel, p298). He explained “mathematics is in principle incapable of demonstrating the quantitative determinations of physics… It is for mathematics a point of honour that all its propositions ought to be rigorously proved, and this made it forget its limits; it seemed an offense to this honour that experience would be acknowledged as alone the source and sole proof of propositions of experience” (Hegel, p234). Experience was the proof of laws of experience, not mathematics, and the attempt to prove empirical laws through maths was conceptually confused and so absurd.

- 5

Sraffa’s physicalist system represents the two poles of the logical arc of capitalism, nominally pure commodity production, which reproduces a stationary state and nothing else, and pure profit production, which produces profits but nothing else. On the one hand, inputs and outputs are identical, nothing changes and so nothing is produced; and on the other hand, surplus arises from nothing, but as something cannot appear from nothing so the surplus is identical to the nothing it was produced from, so nothing is produced. Sraffa’s Being equals Nothing: there is no becoming – no determinate quality or reality, no explanation of how physically incommensurate commodities can be counted or how surplus can arise without equivalent. Sraffa’s system represents nothing twice, the poles remaining purely imaginary and so ideal.

- 6

Money is the universal equivalent of non-equivalent use values. Money as gold is a universal equivalent; it is the innate form of value in a system of private property due to tradition established over centuries. Gold, the universal equivalent, is innately valuable in this system of private property and it may be exchanged for any other commodity, so that when other commodities are exchanged their value is expressed in the universal equivalent price. Valueless symbols, central bank currency, electronic dots, banking debt and credit, may represent gold, and had already largely done so in Marx’s time (gold’s role being limited to settling external trade balances). Later its role was further reduced to an apparently marginal store of wealth held by central banks (as the replacement of gold by valueless tokens that represent a form of money has continued). These near money substitutes embody many of the qualities of the universal equivalents, but they are partial not universal. Currency issued by central banks (dollars, pounds, yuan etc) only circulate commodities within their nation. A power such as the US may issue quasi world money, the US dollar, used by other nations in international trade, but the role of the US dollar remains limited and is declining. It is not a universal equivalent, but dependent on the maintenance of US power. When Russia invaded Ukraine their US dollar assets were seized, cancelled or annulled by the US. Gold cannot be so annulled; its value is universal and not dependent on the proviso of any nation. Hence, as de-dollarisation has accelerated, nations have moved their reserves into gold (the universal equivalent) and therefore away from near money tokens to actual money (gold).