On June 12, 2025, for the first time after more than twenty years, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) board of governors passed a resolution declaring that Tehran was breaching its non-proliferation obligations. The day after, on June 13, Israeli warplanes began a campaign of bombing Tehran and other major Iranian cities. With the help of their proxies inside the country, they assassinated top military commanders, killed leading nuclear scientists at their residence along with their families, bombed the cabinet meeting in Tehran, wounding the President, indiscriminately shelled urban residential areas, and even targeted Evin prison where most political prisoners are incarcerated. The U.S. offered intelligence, refueled their jetfighters in mid-air, and finally entered the war directly by bombing the Iranian nuclear enrichment sites with bunker buster weapons.

This unprovoked Israeli attack happened in the midst of seemingly constructive negotiations between Iran and the U.S. in Rome and Muscat. The Friday the 13th attack happened just before the two countries were to meet on Sunday the 15th to finalize a framework for further agreements on the Iranian enrichment program. In all close to 1000 people were killed in the Israeli attacks, thousands injured, and hundreds of families lost their homes.

There is no solid evidence whether the IAEA board coordinated the release of their report with the Israelis. But the suspicious choreography of the timing of the report’s release with the Israeli attacks affords credibility to the Islamic Republic’s claims that some of the IAEA inspectors spied for Israel. In its report, the IAEA excavated questions from twenty years earlier about highly enriched particles found in three Iranian sites. The case for the Iranian noncompliance is primarily based on the Agency’s conclusion “that these undeclared locations were part of an undeclared, structured programme carried out by Iran until the early 2000s, and that some of these activities used undeclared nuclear material” (my emphasis). Obfuscated in the report was the fact that the IAES has found no evidence of any weaponization program or military component in the Iranian nuclear activities. It was only a few days after the attacks that the IAEA’s Director General, Rafael Grossi, reiterated that “Iran has not been actively pursuing a nuclear weapon since 2003.”

Israel used the IAEA report to legitimize its unlawful military actions. However, such all-out attack was in the making for months, if not years. It could not have been launched simply in response to the IAEA report. For more than two decades, since the established one of the most intrusive regimes of inspections on the Iranian enrichment program, the IAEA had not cited Iran for breach of its obligations. This was not unprecedented. In the 1990s, the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM), whose mandate was to eliminate Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction program, worked closely with the U.S. intelligence agencies. Through UNSCOM, during Clinton administration, the CIA carried out ambitious spying operations to penetrate the Iraqi intelligence and defense apparatus.

Now, the so-called 12-day war is over. Iranians have returned to the devastating perpetual violence of U.S. led sanctions and targeted assassinations by the Mossad. The Trump administration and its European allies have called on Iran to accept its defeat, surrender unconditionally, and “return” to the negotiating table. They ask Iran to dismantle its nuclear technology, halt the production of its advance missile program, cease its support of the Palestinian cause, and terminate its network of what is known as the “axis of resistance” against the Israeli and American expansionism. In other words, become a client state. Iran is one of the few remaining fronts of defiance against the American extortionist posture and the Israeli carnage that has engulfed the Middle East. That defiance comes with a very hefty price.

The United States desires a return to the pre-1979-revolution Middle East alignment, complete with Iran as a client state that shields American interests in the region. For more than four decades this objective has informed the U.S. strategic position toward Iran. Successive American administrations have pursued this policy with campaigns of intimidation, building more than a dozen permanent air base and naval facilities in the region, sabotage, military threats, draconian sanctions, and ultimately, under the Trump administration, bombing nuclear enrichment sites. The U.S. does not necessarily aspire to bring the prerevolution monarchy back to power, though the CIA uses the son of the disgraced Shah as a scarecrow in photo-ops. But it seeks to install a state that lacks the authority to challenge the American regional influence—a state without sovereignty. In the absence of that, perhaps a failed state will do…

The United State has surrounded Iran with permanent military bases to contain any influence the Islamic Republic might assert in regional politics.

The avowed objective of the Israeli government has been the overthrow of the Islamic Republic and the Balkanization of Iran. The Israelis, with the help of their American and European supporters, wish to exploit the multiethnic composition of Iran, particularly the Kurds, Azeris, and Baluchis, and to deepen the tensions between the minority Sunni communities and the ruling Shi‘ite class to replicate a Syrian/Libyan model of the failed state. Since the end of Iran-Iraq war in 1988, the Mossad and the IDF strategists have devised and executed a variety of plans to infiltrate minority opposition groups to foment ethnic unrest to partition Iran. Israel also supports opposition parties, particularly the Mojahedin-e Khalq (MEK) and the royalist organizations of the exiled son of the late Shah, with intelligence, funds, and a vast network of propagandato create instability inside the country. The emergence of the MEK as a Zionist proxy and as mercenaries of the American neocon project shows how deeply the politics of the Middle East has been transformed since the 1979 revolution. A Left, anti-imperialist revolutionary organization in the 1970s, the MEK now hosts John Bolton and Rudy Guiliani as the keynote speakers in their conventions. Israel’s June 13th, 2025, unprovoked attack on Iran was primarily made possible by the Mossad-trained Iranian commandos inside the country. They successfully sabotaged or destroyed the Iranian air defenses prior to the Israeli attacks and made it possible for the Israeli jetfighters to roam the Iranian skies freely.

The twelve-day war on Iran produced two major unexpected results. With their superior airpower and the capacity to decapitate the Iranian military and intelligence apparatus, the Israelis expected a quick dismantling of the regime. They were confident enough to send a voice message to the key military leaders at the commence of operations – instructing them to step down or be killed along with their entire families. The message, leaked to the Washington Post, heard in Farsi, warned: “I can advise you now, you have 12 hours to escape with your wife and child,” said an intelligence operative, whose voice had been altered in the recording. “Otherwise, you’re on our list right now.” Not only did the Iranian military leaders reject that “advice,” but they pulled their wounded command structure together and launched formidable counter offensive missile attacks. Iran inflicted unprecedented destruction deep inside Israel, forcing the Israelis to ask the U.S. for a more direct involvement in the war. As they faced an alarming depletion of their anti-missile interceptors, the Israelis pleaded for an immediate ceasefire. A week into the war, Iran managed to breach the supposedly impenetrable Israeli “iron dome” air defense system.

The second unexpected event of the twelve-day war was the way Iranians rallied around the flag. The debilitating sanctions and the crony capitalism they have fostered have resulted in grave economic hardships for most Iranians. The Israelis believed that their attack would turn that hardship and the ruling classes’ rampant economic corruption into mass protests against the Islamic Republic. Moreover, the political order appeared particularly vulnerable after the year-long “Women-Life-Freedom” protests. Israeli strategists believed that the social discord around gender politics in Iran would resurface after the bombing campaign. That calculus proved wrong; in fact things worked in the opposite direction. Striking Iran with American-made bombs, delivered by American-made fighter jets, falling on peoples’ homes and neighborhoods, revived nationalist sentiment and only gave credibility to the Islamic Republic’s long framing of the United States and Israel as existential threats. The public perception that the Supreme Leader is plagued by “blind paranoia” about Western powers no longer could hold. That fleeting sense of solidarity might not last. But the calculus that said Iranians were ready to accept anything but the Islamic Republic proved to be premature.

For several decades, Western intelligence agencies promoted the idea that Ayatollah Khamenei suffers from a chronic case of paranoia that the United States and Israel are plotting to overthrow the Islamic Republic. These types of images are commonly used in the Western media to depict Khamenei’s paranoiac mindset.

As is so often the case, after the fighting stopped, a war of narratives began. President Trump claimed that the American bombs annihilated the Iranian nuclear sites and forced the Iranian regime to accept their inevitable defeat. He asked the Islamic Republic to surrender without conditions and consent to the American demand of shutting down their enrichment programs. The Israelis celebrated the public demonstration of their intelligence prowess and military might without revealing the extent of damages inflicted by the Iranian missile attacks. Iran proved that they are not another Iraq, Syria, or Libya and can withstand the assault of two nuclear powers. They showed they can and will respond in kind with their own homegrown military muscle.

The war of narratives determines what the next steps will be in the conflict between Iran and Israel and its western allies. The U.S., Israel, and their three willing partners, the UK-Germany-France troika, have made it clear that Iran faces two options, both of which will lead to the client status that the US demands. When they ask Iran to “return” to the negotiating table, never mind that Iran never left it, never mind that Israel is in the habit of assassinating the negotiators, they mean that Iran needs to submit to their terms: stop the enrichment program, shut down their missile production, and terminate their relations with their allies in the region.

To a varying degree, Iranian opposition groups have tried to exploit the Israeli attacks to advance their own agenda. The monarchists, the MEK and other defenders of military intervention believe that the Islamic Republic is now at the brink of collapse and the West needs to act promptly to overthrow the regime in Tehran. Their members collaborated with the Mossad and promoted that collaboration as their patriotic mission to liberate Iran from the yoke of the Islamic Republic.

After the war, a coalition of groups and personalities who have been working from within the existing political order to transform the Islamic Republic, the Reformist Front of Iran, release a statement arguing that the only solution to overcome the current crisis is to accept the terms and conditions put forward by the United States. The statement asks for a series of reforms, such as the release of political prisoners, respect for the freedom of expression, revising laws that promote gender discrimination, free elections, and anti-corruption policies. These are demands that need to be respected. There are many political and civil society actors who have been organizing around those demands and have gain considerable successes on those fronts in the past decades. Many of those actors have paid a hefty price for their activism, from long-term imprisonments to exile or worse. What is troubling in the statement is the coupling of these legitimate concerns with the way it situates Iran in the existing world order–Iran as the pariah. Iran needs to end its hostility toward the existing world order, the statement asserts, and end its international isolation! But how is such a goal accomplished and what conditions do the Islamic Republic need to meet in order to be accepted in that world order? Is there any room in that world order for a nation that refuses to be a client?

A considerable number of those who have worked from within the ruling classes to reform the political order, as well as many public intellectuals subscribe to this hegemonic narrative which maintains that (a) the threats of war against Iran will subside if the Islamic Republic initiates meaningful structural reform to guarantee civil liberties and consent to free and fair elections; (b) Iran needs to respect the existing international order and abide by its laws and conventions; (c) the Islamic Republic is the source of instability in the region and needs to halt its enrichment program, degrade its military capabilities, abandon its regional allies, “the axis of resistance,” and recognize the state of Israel, without holding it responsible for the genocide in Gaza and for attacking Iran.

There is no need to delve deeply into the logic that holds the authoritarian character of the Islamic Republic as the culprit for the Israeli attacks and American hostilities toward Iran. Had repression in Iran disturbed the conscience of American strategists, the United States allies in the region should have been the cradles of democracy in the Middle East. The instrumental appropriation to the cause of human rights and civil liberties in Iran is a mere smoke screen for the Israeli and American expansionist ideologies.

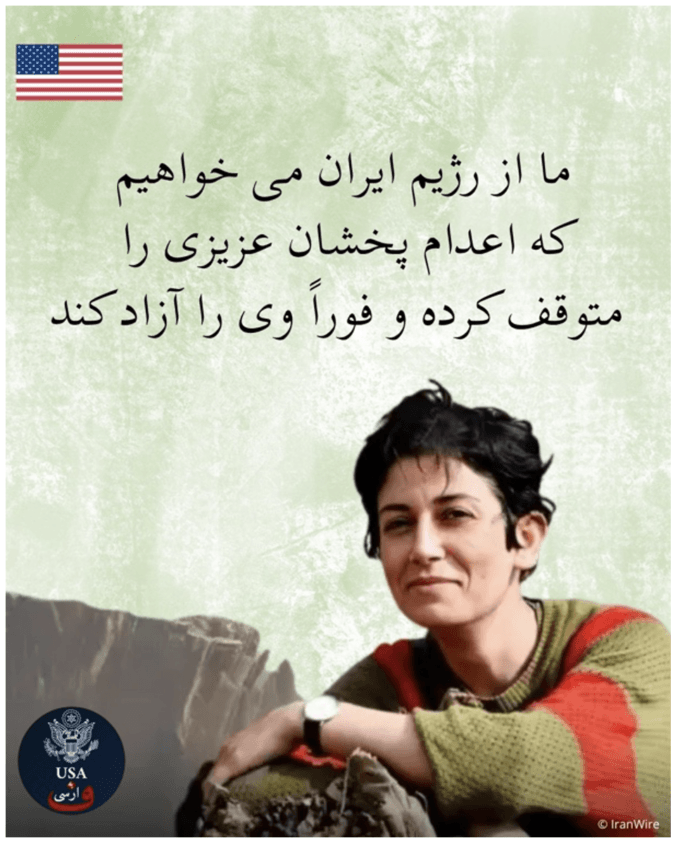

For example, on September 30, 2025, the U.S. State Department Farsi X account posted a photo of political prisoner Pakhshan Azizi on which they plastered a US flag and State Department seal, calling for Iran to revoke her death sentence and immediately release her. The State Department original message in English also called on the Islamic Republic to respect peaceful acts of protest and to stop targeting Kurdish and other ethnic minorities for their legitimate anti-discriminatory demands.

Pakhshan Azizi’s message from prison: The United States must stop warmongering, military attacks, and committing crime in the region

Pakhshan Azizi is a Kurdish social worker who has been active in providing social services and counseling to victims of ISIS in northeastern Syria. She returned to Iran and was arrested in the summer of 2023 on charges of being a member of a Kurdish armed group. She was sentenced to death by a lower court and awaits the results of her appeal. In response to the U.S. State Department’s call for her release, from her death row cell in Evin prison, she sent out a message casting off the American sinister instrumentalization of her case.

I reject all the baseless accusations leveled against me and am in process of appealing the judiciary’s unjust death sentence. I also would like to address the recent statement released by the U.S. Department of State, which appeared to express support for me. If the United States government truly believes in the principles of human rights and humanity, it must first cease its warmongering, aggression, and crimes in the region. It must also end its explicit support for the Zionist regime, which has committed genocide against the people of Gaza. For decades, the U.S. has imposed sanctions and economic blockades that have caused immense suffering and hardship for innocent people. If America genuinely values human dignity, it must bring these inhumane policies to an end. I also hope that the American people will realize that their government’s statements are far removed from compassion and genuine respect for human rights. (translated from Farsi by Yassamine Mather).

From almost the morning after the revolution of 1979 that toppled the Shah’s regime, opposition parties have advocated regime change, believing that the days of the Islamic Republic are numbered. The opposition to the Islamic Republic has taken many different forms, including organized labor movements, civil liberty campaigns, freedom of the press, women’s movements for equal rights and against gender discrimination. But there have always been those who advocated foreign intervention, from the Iraqi invasion of Iran in the 1980s to the latest Israeli-American war on Iran. The 12-day war offered a new hope to those interventionists who believe that servitude of the empire is the price of freedom. Pakhshan Azizi’s message powerfully reiterates that the struggle for social justice cannot find its solution in acquiescence to empire.

Holding Iran solely responsible for regional instability and calling on the Islamic Republic to abide by international treaties and conventions is a curious matter. There is no doubt the Islamic Republic refuses to become a U.S. client, and this refusal explains much in how they resist American dominance in the Middle East and have been competing with the U.S. allies, particularly Israel, for influence in the region. During the past four decades, Iran has built an anti-Zionist coalition primarily as a deterrent, rather than an expansionist, project. The Islamic Republic’s support for the Palestinian cause has always been composed to prioritize the Iranian national interests over the liberation of Palestine. Despite their provocative rhetoric, Iran has never committed any aggression against Israel. Indeed, inside the country, the radical proponents of the Palestinian cause have criticized the state for their inaction in the face of Israeli aggressions, such as a decade-long assassinations of the Iranian nuclear scientists, bombing the Iranian consulate in Damascus, the assassination of the Hamas chief negotiator, Ismael Hanieh, in Tehran, and various kinds of sabotage in the Iranian infrastructure.

The Orwellian demand on Iran to respect international laws when Israel has repeatedly violated the Iranian sovereignty and the United States has illegally bombed Iran’s nuclear sites has no meaning except asking Iran to capitulate to American and Israeli conditions. No other countries in the world have breached international laws as many times as Israel and the United States. The global order to which Iran is bullied to join requires total submission to the interests of American imperialism.

As became evident with the release of Trump’s 20-point Gaza peace plan, negotiation in Trump administration has no meaning except take it or we annihilate you. Like their unilateral proposals to Iran, the White House drafted the Gaza peace proposal without any input from the Palestinians. They revised the original proposal after consultation with Netanyahu and published the final draft as a peace plan without having the other side of the peacemaking, the Palestinians, at the table. The US allowed Netanyahu to create key loopholes in the deal to ensure Israel can continue its Gaza genocide – regardless of the ‘ceasefire’ agreement. In effect, as with Iran, the U.S. and Israel follow the same political logic with Hamas: either surrender or be killed. This logic lacks any assurances that if they do surrender, they will not be killed. And to ensure this lasting peace, they have composed a new “mandate” to govern Palestine under the viceroyship of the former British Prime Minister Tony Blair. The uncanny reference to a “mandate” is another display of unbridled imperial ambitions that the U.S., Israel and their European allies pursue.

Many Iranians are exhausted from decades of sanctions and a repressive state apparatus to which the sanctions afford more legitimacy and longevity. It is not surprising that many inside the country are ready to throw up their hands and take whatever deal the United States offers. There is an awareness inside the country of the Balkanization of Iran as a real possibility, so too the “failed state” Libyan/Syrian/Iraqi scenarios of total disintegration of society. At the same time, continuing life in the purgatory of constant threats of war and destruction, while managing the effects of the draconian sanctions inflicted on the country has been pushing large segments of the polity, public intellectuals, and general population toward a politics of resignation.

There remain no good options for the Islamic Republic and for the subjects over which it rules. The U.S.-Israeli war on Iran momentarily collapsed the distinction between the state and the nation. As the unifying influence of the war fades, Iranians of all walks of life find themselves faced with the unresolvable economic deprivation and disparity while the beleaguered state grapples with the boundless avarice of the American empire and its cronies. Iranians need to decouple the defense of the country’s sovereignty from the struggle for social justice and civil liberties. It remains to be seen whether Iranian sovereignty will remain intact after the dust of the war settles. That is if the dust of war ever settles with the Israeli ambitions and the West’s desire to hold the pen for redrawing the map of the Middle East.

Behrooz Ghamari is affiliated with the Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali Institute of Iranian Studies at the University of Toronto. He is the former Chair of the Department of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University and the author of Islam and Dissent in Postrevolutionary Iran (2008); Foucault in Iran: Islamic Revolution after the Enlightenment (2016); Remembering Akbar (OR/Books, 2016); and the forthcoming book The Long War on Iran: New Events and Old Question (OR/Books, January 2025).