Is It about the Oil?

“No War for Oil” is one of the most popular slogans in the many emergency demonstrations sprouting up around the world in response to the criminal kidnapping of Nicolas Maduro and Cilia Flores from their residence in Caracas, Venezuela and their forced removal to detention in the US.

For many outraged by the naked military aggression on Venezuelan sovereignty, the abduction is an escalated step toward the capture of Venezuelan energy resources by the US government, given that Venezuela has the largest proven petroleum reserves of any country at this moment.

The argument goes that– when you pull the curtain back– the ultimate goal of US imperialist designs is the control over and possible exploitation of Venezuela’s most important resource.

Having argued frequently that oil-imperialism or energy-imperialism is often an important– if not decisive– factor in capitalist foreign policy, this claim is appealing. Since the time when Britain in the early twentieth century turned from coal-burning naval ships to oil, petroleum has become more and more essential for the functioning, growth, and protection of capitalist economies. Consequently, intense competition for a rapidly diminishing, increasingly hard to discover, and growing-costly-to-exploit resource dictates the actions of great power rivals.

History gives us important examples of resource-scarcity spurring devastating imperialist aggression by capitalist powers. Nazi Germany’s Lebensraum program had at its core the necessity of acquiring energy resources to propel its imperialist designs– a program that led to world war. Similarly, Hirohito’s Japan– a resource-poor island nation– launched its Pacific offensive largely to acquire the oil to continue its war against China in the face of a US embargo.

The US embargo to deny oil to Republican Spain was, conversely, an aggressive act in oil imperialism, as is today’s blockade of Cuba. The war in Ukraine is indirectly a war over energy resources, since US resolve was stoked by the opportunity to win the vast EU market from Russia– a convenient, inexpensive, and formerly reliable supplier.

Less well known, the major oil and gas suppliers are constantly influencing global politics through manipulating production and prices. The most well-known example is the 1970’s OPEC oil strike against Israel’s Western supporters (an act that the Arab countries have lost the stomach for in recent times).

As a wise friend speculated once: “Why do you think the US never occupied Somalia after the Battle of Mogadishu in 1993 left 92 US casualties? Because there was no oil!”

Yet many believe that the attack on Venezuelan sovereignty was not about the oil… even with the President of the aggressor state saying that it was!

Instead, they believe it was about Western values, the rule of law, democracy, petty grievances, hubris, or even drug smuggling. Those in the loyal opposition– Democratic Party leaders– share many of these same explanations, but fault the Trump administration for its procedural or legalistic errors.

The center-left, the bogus-left, and the anti-Communist left deny that oil could be the motive because they imagine that it might bolster the case for an explanation based upon classical Leninist imperialism– that the invasion of Venezuela was motivated by corporate interests, by exploitation of resource-rich countries.

Thus, widely-followed liberal economist Paul Krugman scoffs at the idea that Venezuela was invaded for oil: “… whatever it is we’re doing in Venezuela isn’t really a war for oil. It is, instead, a war for oil fantasies. The vast wealth Trump imagines is waiting there to be taken doesn’t exist.”

Krugman collects and endorses the most popular arguments against the “war for oil” viewpoint:

Venezuela reserves are a lie.

Venezuela’s heavy crude oil is uneconomic, undesirable, and unwanted.

The Venezuelan industry is so decrepit that it is beyond rescue.

The US has so much sweet, light crude oil available at low cost that no one would want Venezuelan oil.

The Nobel prize award-winner’s dismissal could easily be dismissed by simply asking why– if acquiring Venezuelan oil is so pointless– did Chevron ship 1.68 million barrels of Venezuelan crude oil in the first week of January, according to Bloomberg?

And then there is the ever-voracious, parasitic Haliburton– the consummate insider corporation– that announced that it’s ready to go into Venezuela within months!

It is worth looking a little deeper into the reasons that Venezuela’s oil is a possible target of imperialist design.

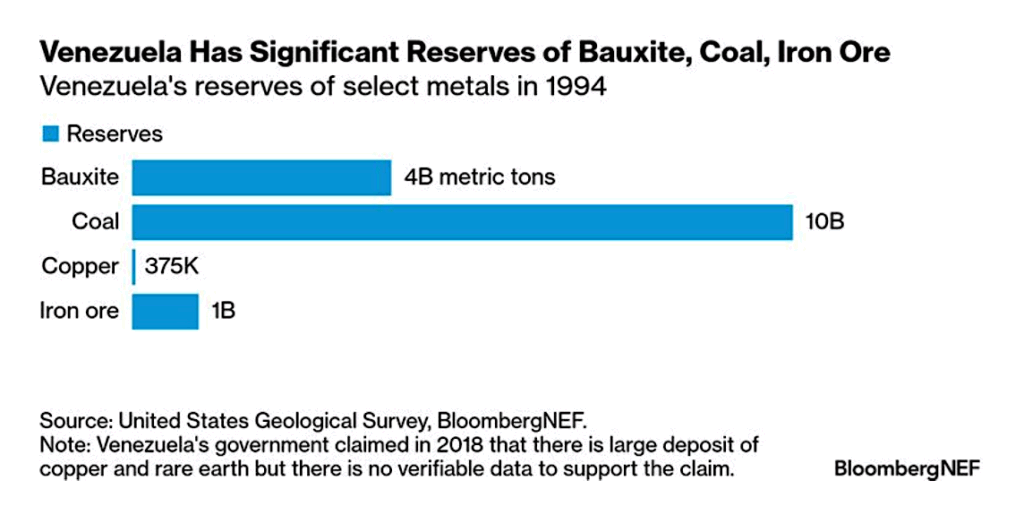

If Venezuela’s oil reserves are even one-third of what OPEC, The US Energy Information Administration, or The Energy Institute concede, their reserves would still be double those of the US.

While Venezuela’s heavy, sour crude is costlier to extract and refine, it remains as a legacy with many refineries in the US that were established before the shale boom. Naked Capitalism concedes that “[i]t is true that the US has motive, in that our refineries are tuned so that 70% of the oil they process is heavier grades, despite the US producing light sweet crudes.” It further quotes The American Fuel and Petroleum Manufacturer’s website:

Long before the U.S. shale boom, when global production of light sweet crude oil was declining, we made significant investments in our refineries to process heavier, high-sulfur crude oils that were more widely available in the global market. These investments were made to ensure U.S. refineries would have access to the feedstocks needed to produce gasoline, diesel and jet fuel. Heavier crude is now an essential feedstock for many U.S. refineries. Substituting it for U.S. light sweet crude oil would make these facilities less efficient and competitive, leading to a decline in fuel production and higher costs for consumers.

Currently, Canada exports 90% of its very heavy, sour oil to the US, accounting for approximately a quarter of its total exports to the US. Oil from the Alberta oil sands is also expensive to extract and refine, but nonetheless amounts to 4 to 4.5 million barrels per day exported to the US. It must be acknowledged that future Venezuelan oil counts as powerful leverage in the recent and continuing political and economic friction between the US and Canada, especially as Canada is defying the US by building “a new strategic partnership” with China.

Much has been made of the state of the Venezuelan oil industry, today producing around a million barrels a day, down from its peak at over 3.5 million barrels per day decades ago. Indeed, the US blockade has stifled investments, shuttered export markets, and denied technological advances. Nonetheless, Venezuela has produced as much as 2 million barrels a day as recently as 2017. Admittedly, it would take significant investment to return to the 2017 level and vast investment to restore the level of the 1970s.

Many commentators are “shocked” by the enormous capital required to upgrade the Venezuelan oil industry. They forget earlier “shocking” assessments of the fracking revolution: “The U.S. shale oil industry hailed as a “revolution” has burned through a quarter trillion dollars more than it has brought in over the last decade. It has been a money-losing endeavor of epic proportions.”

Still, the Trump administration’s gambit has many competitors concerned that US control over Venezuela’s oil “would reshape the global oil map–putting the US in charge of the output of one of the founding members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and, along with America’s own prodigious production, give it a potentially disruptive role in a market already struggling with oversupply.” According to the Wall Street Journal, US oil production, US political and corporate domination of Guyana’s emerging energy sector, and now Venezuela’s reserves, may place the US in a position to unbalance the market, particularly at the expense of the OPEC alliance, a move of enormous political consequence.

The critics of oil-imperialism fail to understand all of its dimensions. They crudely simplify the politics of oil to the immediacy of extraction and its costs of the moment, ignoring indirect impacts, the wider prospects, and the longer term.

Nor do they grasp the issues that are facing the US domestic oil industry. While fracking has allowed the industry to return to being the largest crude oil producer in the world, the industry faces the perennial question of peak production for a given technology– the ever-present problem of rising costs of discovery and extraction. Further, the exalted Permian Basin is “becoming a pressure cooker”, pressing upon both costs and public acceptance. “Swaths of the Permian appear to be on the verge of geological malfunction. Pressure in the injection reservoirs in a prime portion of the basin runs as high as 0.7 pound per square inch per foot, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of data from researchers at the University of Texas at Austin’s Bureau of Economic Geology.” As The Wall Street Journal also reports: “A buildup in pressure across the region is propelling wastewater up ancient wellbores, birthing geysers that can cost millions of dollars to clean up. Companies are wrestling with drilling hazards that make it costlier to operate and complaining that the marinade is creeping into their oil-and-gas reservoirs. Communities friendly to oil and gas are growing worried about injection.”

Because of the current glut of oil (likely retaliation by OPEC+ producers seeking to drive down US production below its cost of production and recover market share) the number of operating rigs is down 14% in the Permian. Oil markets are volatile, competitive, and transient. Where Venezuelan crude will fit into these equations remains an open question.

And then there is the Essequibo, a region currently within the borders of Guyana, but disputed by Venezuela. Recent discoveries in the area promise a potential of over 11 billion barrels of oil, with Exxon estimating a production of 1.7 million barrels per day by 2030. This economic plum is now off the table in the conflict between the Maduro government and Guyana and Exxon. As OILPRICE.com puts it succinctly: Trump’s Venezuela Takeover Will Make Guyana Oil Safer… for the US and Exxon.

Let us not forget China. The People’s Republic of China has granted around $106 billion in loans to Venezuela since 2000. Daniel Chavez, writing in TNI, notes that those loans place “it fourth among recipients of Chinese official credit globally.” Estimates vary, but the PRC imports between 400,000 and 600,000 barrels per day from Venezuela, at least doubling since 2020. While it is less than 5% of PRC usage, it is not inconsequential. And it represents a serious penetration of capital and trade in the Western hemisphere– the US sphere of interest.

It underscores the reality that oil-politics is not merely about the immediacy of reserves, extraction, costs, and price, but also about competition and rivalry within the imperialist system. The competition and conflict between the US, Venezuela, Guyana, Canada, PRC, OPEC, and other oil-producing countries is intrinsic to a system that lives and breathes thanks to its exploitation of energy resources. In that regard, it is still most clearly viewed through the prism of Lenin’s theory of advanced capitalism devised over a hundred years ago.

I give the last word to the informed and serious student of the oil industry, Antonia Juhasz:

If the greatest lie the devil ever told was to convince us that he wasn’t real, the greatest lie the oil industry ever told us is to convince us that they don’t want oil. Where do we even begin to think about that as possible? They want to control when they produce it and how, and under what terms. They need to show a growing amount of oil that they can count as their reserves.

There are very few big pots of oil left sitting around anywhere unclaimed. The only way to get that is to increase technology, go into very expensive, technologically complex modes of production that face a lot of resistance. Venezuela is a country that [the big oil companies] were producing in not that long ago and making money in not that long ago and have wanted to get back into but on their own terms.

So I think when they protest publicly, one, it’s to distance themselves from Trump’s extremism, but two, it’s a great public negotiating tactic. They’re basically saying publicly, and the media is repeating it, “We wouldn’t want to operate in Venezuela. Oh, my God, it’s expensive, it’s technologically complex.” I actually think those are ridiculous things if you look where else they operate.