LIBERTARIAN ANTI-IMPERIALISM

Trumpy Puts Washington’s War Machine Out On Loaner to Bibi!

The sheer barking hypocrisy of the Donald’s, yes, unprovoked and senseless attack on Iran over the weekend is surely one for the record books. After years of noisy campaigning against the Forever Wars and 12 months back in the Oval Office spent in hot pursuit of a Nobel Peace Prize, the Donald has not only started an utterly unnecessary new and very hot war, but did it essentially by gratuitously putting America’s vast War Machine out on a “loaner” to Bibi Netanyahu.

That is to say, there is not a single plausible reason based on America’s Homeland Security for attacking Iran, as we amplify below. So what we have is an utter betrayal of everything Trumpy has ever said because once again Bibi Netanyahu bamboozled the man’s smallish brain, negligible knowledge of the region’s history and his gigantic ego into the goddamned dumbest foreign military intervention by Washington during the last half-century. And that includes a lot of stupid-ass competition.

Trump on the campaign trail: “We are finally putting America First. Our policy of war regime change and nation-building is being replaced by the pursuit of American interests… It is the job of our military to protect our security, not to be the policemen of the world.“

President Trump in 2020: “We’ve spent $8 trillion in the Middle East and we’re not fixing our roads in this country? How stupid. How stupid is it? And we’re not fixing our tunnels, our bridges, our hospitals, our schools? It’s crazy.”

Even pedigreed neocon Max Boot is flummoxed:

At one time, I had thought that President Donald Trump had reached similar conclusions (about the folly of Iraq). He denounced the Iraq War as “the biggest single mistake made in the history of our country,” criticized “nation-builders,” and vowed to “measure our success” by “the wars we never get into.”

Now, if this were just a standard case of the kind of political hypocrisy that is par for the course in Washington, Trump’s Iran attack might be dismissed as more of the same old, same old. You might even say the sheeples of America should not by surprised that the ravenous wolf they knowingly re-elected wasn’t a vegetarian after all.

Indeed, you might well conclude, as we have, that Donald Trump has now proven himself to be the most deceitful fraud in US political history. But even that wouldn’t be the whole story or even the most important part of it.

Unfortunately, there are far more insidious forces at work in this horrific turn of events than just standard political hypocrisy and campaign lies. What we really have here is a vast war machine, a false neocon foreign policy narrative and an infrastructure of Empire so deeply embedded in the very warp and woof of America’s process of governance that the outcomes of elections have become essentially immaterial. Or as our friend Tom Woods astutely observed, elections don’t matter much because we always elect John McCain.

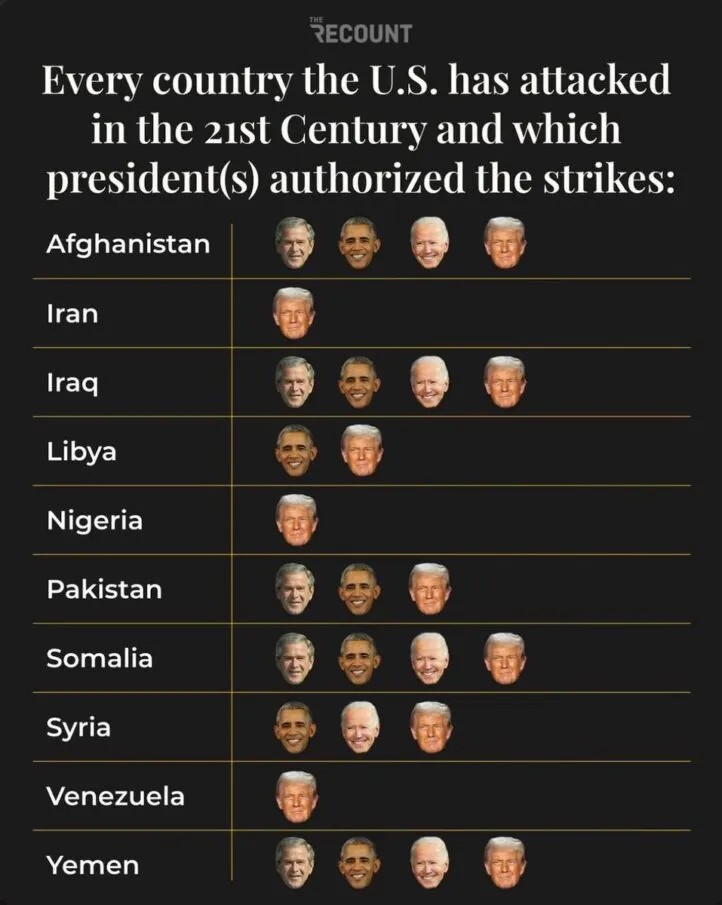

And it seems to be getting worse with time. In fact, here is the box score for the last 10 US military interventions and the number of them embraced by each of America’s four presidents during the 21st century to date. The Donald is winning hands down:

- George Bush the Younger: 5/10.

- Joe Biden & auto-pen: 5/10.

- Barack Obama: 7/10.

- Donald Trump: 10/10.

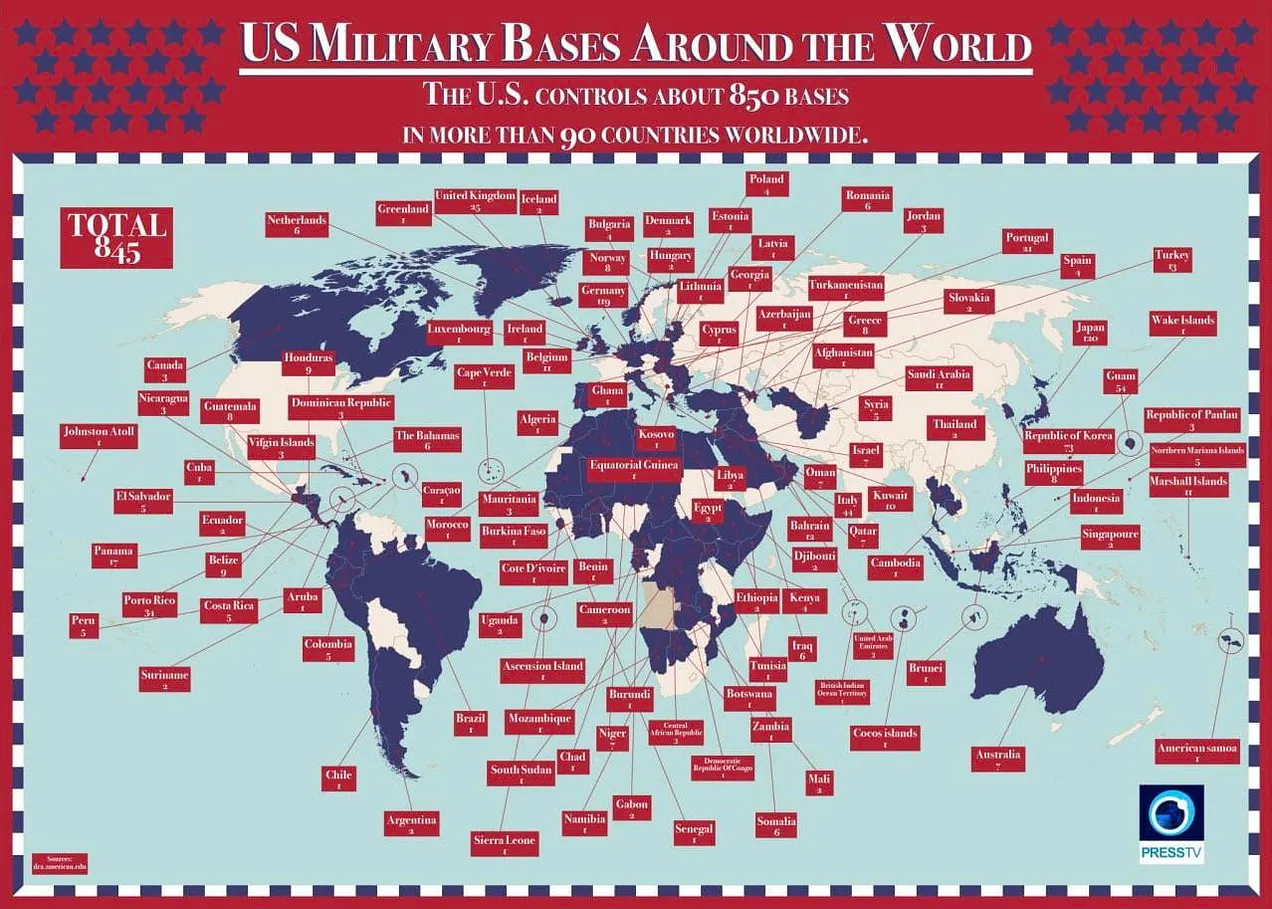

In further pictorial terms, the map below shines a flashing neon light upon the real culprit. To wit, after Washington has been in the Empire business for more than seven decades running the daily working narrative on the banks of the Potomac is utterly steeped in militarism, foreign wars and Washington meddling in the affairs of virtually every country and statelet on the planet owing to—

- the endless projects and globe-spanning operations embedded in the massive $1 trillion Department of War budget.

- the vast campaign funding, lobbying and think tank operations of the phalanx of arms merchants which feed upon it.

- the doings of the planet-circling foreign aid, security assistance, US govenrment propaganda organs, NED and NGO complexes.

- The endless busybody activities of the Congressional national security committees, the perpetual scurrying about town of visiting foreign factotums and the immense outward flow of Washington junketeers and plenipotentiaries to the far flung outposts of the American Empire.

If there were a case for Empire, of course, all of this embedded distraction and institutional bias for meddling and war abroad might be considered unavoidable collateral cost. But here’s the thing: There is simply no homeland security case for Empire now, nor has there ever been.

And not just since 1991, when the Soviet Union tumbled into the dustbin of history. The liberty and security of Americans from sea-to-shinning-sea has not depended upon Washington’s global empire even since 1947/1948/1949 when the Pentagon, CIA, Marshall Plan and NATO all got launched and institutionalized in the name of combating the Soviet Union and world communism.

The fact is, even back then America did not need “alliances” and “collective security” to deal with the limited military threat posed by the Soviet Union, whose days were always numbered and threat sharply circumscribed by the inherent social and economic dysfunction of Communism. What America needed back then was just an invincible nuclear deterrent, which it had all the way through the Cold War and did not need allies to execute.

Moreover, whatever dubious conventional military threat that the exhausted Red Army might have posed to Europe after 1945 was their problem alone; and, as the now open Soviet archives prove, it wasn’t material anyway because Stalin and his successors never had an intent or even semblance of a plan to invade western Europe.

The whole Soviet conventional threat was but a military-industrial complex cover story for selling tanks, planes, missiles and warships, and also for keeping the apparatchiks of the national security complex occupied with globe-spanning busybody-work and endless “national security” schemes to justify their existence more than anything else.

To be sure, the misbegotten US military umbrella over Europe enabled its ruling socialist parties—both the left-wing types and the Christian democratic versions—to have a mushrooming Welfare State. Yet one accompanied by merely crushing rather than catastrophic taxes owing to impecunious defense budgets backstopped by the Washington War Machine.

Of course, when the Soviet bogeyman disappeared entirely in August 1991, there was no reason left for NATO, globe-spanning allies, worldwide bases, two-and-one-half war fighting capability or any of the other accoutrements of Empire. Yet 35 years latter the sheer insanity of the 845 bases and military installations still doting the planet is testimony to the suffocating grip that the Empire holds upon the governing machinery and the narratives which drive it on the banks of the Potomac.

Most especially, there is no reason for a single one of the bases that are crowded cheek-by-jowl into the Persian Gulf and middle east. The military defense of the American homeland needs only the same invincible nuclear deterrent that kept the peace during the cold war and a Fortress America wall of coastal and airspace defenses on the interior side of the great Atlantic and Pacific moats.

That’s it. No allies. No bases putting US servicemen’s lives in harms way. No Fifth Fleet patrolling the eastern Mediterranean, Red Sea, Persian Gulf or Indian Ocean.

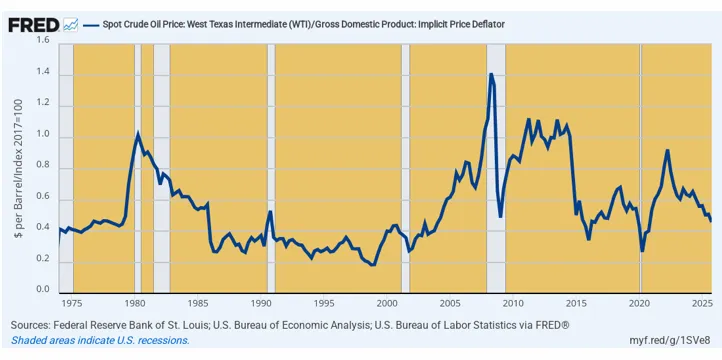

And, no, the “but oil” canard doesn’t cut it, either. We now have the lessons of 53 years since the so-called Arab Oil Embargo of October 1973, which make it abundantly clear that Mr. Market and a modest strategic petroleum reserve is all we need to take care of the oil price and availability matter—not Persian Gulf bases, $25 billion carrier battle groups, massive air and sealift capacities and infantry divisions at the ready to enable wars of invasion and occupation on a moments notice.

In short, oil is about the revenue, stupid!

Any state in control of significant oilfields will produce the oil and sell it on world markets because always and everywhere they need the revenue to fund state operations, domestic welfare and military capacities. For crying out loud, even the noisily hostile mullahs of Iran never withheld a drop of oil production. That’s because they desperately required the oil revenue to keep their battered nation of 90 million afloat; it was the armchair warriors on the banks of the Potomac, in fact, who embargoed their production and curtailed supplies to the world market.

Even the head-choppers of ISIS, who briefly controlled the oilfields of eastern Syria, squeezed every drop they could from their wheezing old wells in that area because they needed the money.

Moreover, it has been proven time and time again that Mr. Market does his job with alacrity when supplies are temporarily curtailed, even with regard to the 20 mb/d flowing through the Strait of Hormuz. The proof of the pudding is right here in the graph of the constant dollar global crude oil price: At the 53-year marker since the short-lived 1973 oil embargo, constant dollar prices stand no higher today than they did way back then, and have never escaped the $60-$80 range (2025 $) for more than a few years.

Index Of Constant Dollar WTI Oil Price, 1974 to 2026

In short, the map of Washington’s global empire depicted below is utterly and completely irrational in the world of 2026. But its very existence and all the machinery and interests behind it explain why even a “no more wars” loudmouth like Donald Trump ended up launching the stupidest and potentially most dangerous war yet since 1945.

After all, the thin veneer of reasons for Trump’s military madness beyond oil amount to canards like “but allies”. Or but “they killed US soldiers “. And most especially but “they’re bad actors” in the region. Yet none of these matter to America’s Homeland military security, either.

To wit, an invincible nuclear deterrent and Fortress America conventional defense doesn’t need any allies in the middle east at all, including Israel. The latter is not remotely the unsinkable aircraft carrier it’s purported to be—even as the fanatical anti-Iran obsessions of Bibi Netanyahu have repeatedly dragged Washington into utterly unnecessary conflict with Tehran—the very Mother of which is now raining down upon us.

Moreover, every single American soldier who has been a casualty of Iran or its proxies since 1979 were in harms’ way only because of US bases in the middle east or deployments to locations there which have no other reason than backstopping Israel’s military. By contrast, no American soldier or civilian for that matter, has been killed on American soil at the hands of Iran’s mullahs.

Thus, the infamous killing of 181 US soldiers by alleged Iranian proxies way back in 1983, for example, happened in Beirut, owing to the misguided stationing there of US “peace-keeping” troops. Their mission was to quell the uprising in southern Lebanon by the incipient forces of Hezbollah after Israel had conducted a scorched earth invasion in pursuit of the PLO and Yasser Arafat.

Needless to say, upon this tragedy, Ronald Reagan recognized his mistake, redeployed the remaining US marines to the safety of an aircraft carrier in the deep Mediterranean and moved on to more legitimate matters of state. He didn’t to seek to avenge for these deaths even then—so what in the hell is the Donald talking about 43 years later?

Even reciting the Lebanon barracks disaster is proof that in doing Bibi’s bidding he is grasping for straws.

Likewise, how Iran is governed or misgoverned internally is most surely none of Washington’s business way over here 10,000 kilometers from Tehran.

For crying out loud, Donald. Neither God, the UN or anyone else with authority on planet earth appointed you as dispense-in-chief of “justice” in Iran, Venezuela or anywhere else outside the boundaries of America.

Yet these bogus reasons—and most especially the blinking absurdity of bringing “justice” to the long suffering people of Iran—are all that the Trump Administration can offer for its insensible military action this weekend.

In that context, we needs start with Trump’s risible claims that—

“……our objective is to defend the American people by eliminating imminent threats from the Iranian regime”

But there were none. Full stop. End of story.

The two threats he cited—-Iran’s nuclear and missile programs—were neither imminent nor even real threats at all. With respect to the hoary claims of an Iranian nuke just around the corner, the Donald’s own head of the ODNI (Office of the Director of National Intelligence), Tulsi Gabbard, made it clear as recently as her testimony to the Senate Intelligence Committee in March 2025 that Iran has no active program to weaponize the uranium is was enriching for its nuclear power reactor and medical purposes:

“The IC continues to assess that Iran is not building a nuclear weapon and Supreme Leader Khamenei has not authorized the nuclear weapons program that he suspended in 2003… We continue to monitor closely if Tehran decides to reauthorize its nuclear weapons program.”

That’s right. No weaponization program—which even then was just research—since 2003; and that’s based on an intelligence finding which did not come out of the blue just 11 months ago.

To the contrary, Gabbard’s statement quoted above was in line with all the statements and NIEs (National Intelligence Estimates) delivered by the the 17 US intelligence agencies going back to 2007,when the NIE issued that year stopped George Bush the Younger in his tracks, after he had been persuaded to launch an all out attack on Iran similar to the Donald grotesque action this weekend.

But as he said in his Memoirs, “how could I bomb Iran for having a nuke that my own intelligence committees said they didn’t have?”

2007 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE):”We judge with high confidence that in fall 2003, Tehran halted its nuclear weapons program… We assess with moderate confidence Tehran had not restarted its nuclear weapons program as of mid-2007… Tehran’s decision to halt its nuclear weapons program suggests it is less determined to develop nuclear weapons than we have been judging since 2005…….Our assessment that Iran halted the program in 2003 primarily in response to international pressure indicates Tehran’s decisions are guided by a cost-benefit approach rather than a rush to a weapon irrespective of the political, economic, and military costs.”)

Year after year, the NIEs have been tracking the same language. In fact, in 2012 an Obama official repeated almost the exact language in one of many open public testimonies:

“We judge Iran’s nuclear decision-making is guided by (the above 2003 NIE’s) cost-benefit approach, which offers the international community opportunities to influence Tehran.”

Even by 2023 the story was the same under Biden:

Unclassified ODNI Report on Iran’s Nuclear Weapons Capability (July 2023 edition): “Iran is not currently undertaking the key nuclear weapons-development activities that would be necessary to produce a testable nuclear device…”

Of course, just last summer Trump claimed to have “totally obliterated” the Iranian nuclear program including much of its centrifuges and enriched uranium stockpiles. So there’s no way on god’s green earth that it could have reconstituted its enrichment capacity, produced hundreds of kilograms of 90% enriched, weapons grade material, and then produced a weaponized nuke based on engineering capacity that the US intelligence community has consistently attested it abandoned 23 years ago.

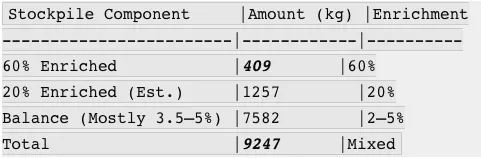

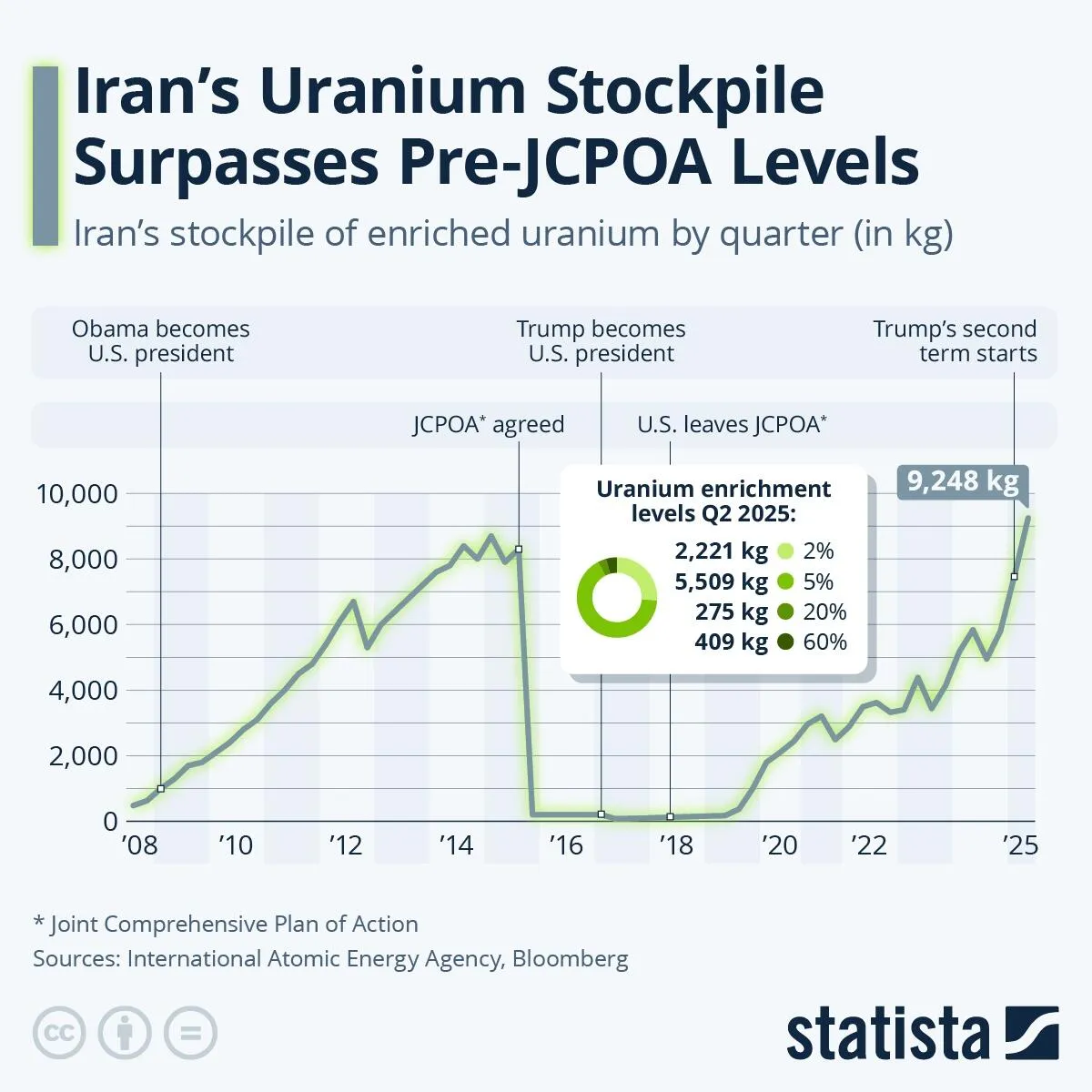

And even that’s not the half of it. As we have previously explained, even the small 420 kilogram (kg) stockpile of 60% uranium (out of total stocks of about 9,000 kgs) that the International Atomic Energy Agency says it had at the time of the June bombing had been produced for bargaining chip purposes in the context of the negotiations with the Trump Administration then underway.

As a NPT (nonproliferation treaty) signatory and operator of a 3,000 megawatt civilian nuclear reactor at Bushehr, Iran was allowed to have the 7,582 kilograms of civilian reactor grade enriched uranium that the IAEA also certified last spring, as well as the 1,257 kilograms of medical grade uranium (20%).

What was really up for debate was just the 409 kilograms of 60% enriched material in its possession that could be spun to 90% weapons grade in a relatively short time.

But for crying out loud, it is goddamn obvious to anyone not looking for an excuse for war that Iran had produced this material as of last June as a bargaining chip. That is, in order to get a new nuke deal with Washington to replace the one the Donald himself unilaterally cancelled in 2018, and thereby pave the way for lifting the brutal and demented economic sanctions that Washington has again imposed on Iran.

Iran’s Enriched Uranium Stockpiles As Of May 2025

The proof of the bargaining chip pudding could not be more evident in the graph below. During the 10-year run-up to the 2015 nuke deal with the Obama Administration, the Iranians increased their enriched uranium stock piles to just slightly below the current level, to about 9,000 kilograms. But in an almost mirror image of the present, only about 350 kilograms of that material was enriched to the 60% purity level or the threshold of weapons grade HEUs.

That is to say, it was generated as a bargaining chip, and that was exactly its fate. Upon activation of the JCPOA in 2015, all of the 60% material was destroyed as certified by the IAEA.

At the same time, the total stockpile of civilian grade material was also reduced by 97% to de minimis working levels, as further certified by the IAEA. Indeed, Iran ended up retaining only 300 kilograms of its 9,000 kilogram stockpile—an amount that could have been readily stored in the Donald’s wine cellar at Mar-a-Lago.

As it happened, of course, the Donald recklessly canceled the deal in May 2018 on the grounds that it had to be a bad deal by definition because he didn’t negotiate it!

Of course, that foolish move only caused the Iranians to restart the stockpiling process yet again, as is so explicitly depicted by the green line in the graph below.

The irony, therefore, is that after the Donald’s feckless June bombing campaign the Iranians likely had close to 100% of the 9,248 kilograms (including the 409 Kg of 60% material) held before June still in tact. That’s based on pretty convincing satellite photos showing that all of the Donald’s amateur “art of the deal” head fakery last June about “two weeks to decide” before the actual the bombing runs enabled the Iranians to drive trucks up to the Nantanz and Fordow facilities and remove the stockpiles to safe sites elsewhere.

Stated differently, Obama negotiated the Iran enriched stockpile to down by about 97%, while the Donald bombed roughly the same level of stockpile from 9,000+ kilograms to, well @ 9,000 kilograms!

And yet and yet. The “obliterated” material which was neither illegal, even remotely anything like a real nuke and likely not obliterated, either. Yet this weekend it became just another version of the flat-out Big Lie that Netanyahu has been telling for decades.

Indeed, for want of doubt here is but a smattering of Bibi’s endless lying about Iran’s purported nuclear bomb threat. And yet it is on the basis of this rote lie that the Donald has loaned out America’s war machine to one of the most demented warmongers are the planet today.

- 1992 (Knesset address as MP): “Within three to five years, we can assume that Iran will become autonomous in its ability to develop and produce a nuclear bomb.”

- 1995 (in his book Fighting Terrorism): Iran would have a nuclear weapon in “three to five years.”

- 1996 (address to joint session of U.S. Congress): “The deadline for attaining this goal [nuclear weapons] is getting extremely close.”

- 2009 (to U.S. congressional delegations, per WikiLeaks cables): Iran was “probably one or two years away” from developing weapons capability / “Iran has the capability now to make one bomb… they could wait and make several bombs in a year or two.”

- Early 2012 (closed talks with Israeli officials, reported by Israeli media): Iran is just “a few months away” from attaining nuclear capabilities.

- September 16, 2012 (U.S. television interviews): Iran is “6-7 months” from nuclear bomb capability.

- September 27, 2012 (UN General Assembly speech):

“By next spring, at most by next summer… they will have finished the medium enrichment and move on to the final stage. From there, it’s only a few months, possibly a few weeks before they get enough enriched uranium for the first bomb.”

“Before Iran gets to a point where it’s a few months away or a few weeks away from amassing enough enriched uranium to make a nuclear weapon.” - March 3, 2015 (address to joint session of U.S. Congress):

“With this massive capacity, Iran could make the fuel for an entire nuclear arsenal and this in a matter of weeks, once it makes that decision.”

“The foremost sponsor of global terrorism could be weeks away from having enough enriched uranium for an entire arsenal of nuclear weapons and this with full international legitimacy.”

(He also noted Iran’s breakout time under the proposed deal would be “very short – about a year by U.S. assessment, even shorter by Israel’s,” but stressed post-deal risks of rapid weaponization via existing infrastructure.) - June 2025 (public statement amid Israeli strikes on Iran): “If not stopped, Iran could produce a nuclear weapon in a very short time. It could be a year. It could be within a few months.”

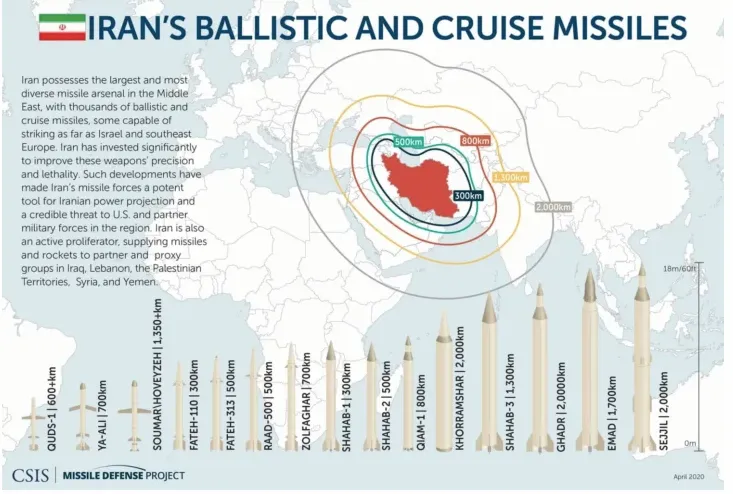

As we will amplify further in Part 2, there is no evidence that Iran is actively developing intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of hitting the U.S, either.

The Defense Intelligence Agency warned last year that Iran could produce such a missile by 2035 if it chose to do so. But its missile production facilities and launch sites were severely damaged in June, and, while there is evidence of Iran rebuilding its capacity to manufacture short- and medium-range missiles, the evidence of ICBM development is utterly lacking.

And as for the here and now, the graphic below tells you all you need to know. Even with a magnifying glass you can’t find Washington DC, New York, Boston or any other US city on the map below because they are all 10,000 kilometers or ore away from the red area depicting Iran in the center of the concentric range circles. But none of them are more than 2,000 kilometers out because that has been Iran’s stated policy do avoid any suggestion that it is targeting the US homeland.

It is not now, nor has it ever had either the intention or capacity to harm the hair on the head of a single American citizen domiciled from sea to shinning sea.

So what the weekend attack? Apparently, the Donald is still waiting for exact instructions from Bibi, as we will amplify in Part 2.

David Stockman was a two-term Congressman from Michigan. He was also the Director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Ronald Reagan. After leaving the White House, Stockman had a 20-year career on Wall Street. He’s the author of three books, The Triumph of Politics: Why the Reagan Revolution Failed, The Great Deformation: The Corruption of Capitalism in America, TRUMPED! A Nation on the Brink of Ruin… And How to Bring It Back, and the recently released Great Money Bubble: Protect Yourself From The Coming Inflation Storm. He also is founder of David Stockman’s Contra Corner and David Stockman’s Bubble Finance Trader.

How US/Israeli Iran Strikes Will Penalize Global Prospects

On February 28, 2026, President Trump announced the start of Operation Epic Fury. In a surreal twist, he described the mission’s primary objective as defending the American people by eliminating “imminent threats” from the Iranian regime.

Trump specifically cited the need to eliminate Iran’s nuclear ambitions, destroy its military infrastructure and undermine Iranian-backed groups in the region. He delegated regime risk to the Iranian people urging them to “take over your government.”

With Israel, the US hoped to “decapitate Iran’s leadership”, particularly Ali Khamenei, Iran’s Supreme Leader, and President Masoud Pezeshkian. This has been the US/Israeli dream since the Islamic Revolution almost half a century ago: to rule and divide the polity and fragment the economy, to dominate the energy resources.

In the absence of the US/Israel escalation in the region since early 2025, the 86-year-old Khamenei would likely have retired. But that was no option to either the US or Israel. His death was deemed vital to serve as a demonstration effect.

Masoud Pezeshkian was elected as a reformist in the July 2024 Iranian presidential election. The first reformist to hold the presidency in Iran in some two decades, he campaigned on a platform of moderation, pledging to relax the strict enforcement of hijab laws, improve relations with the West, restart nuclear negotiations to ease economic sanctions, and to end Iran’s international isolation.

In the US and Israel, Iranian reformism is seen as a threat. Development, women’s rights, Western ties, eased sanctions, international cooperation – it all worked against the goal to control Iran’s energy resources and restructure the Middle East. Hence, their preference for a pro-US Iranian proxy, including Raza Pahlavi, the son of the former Shah of Iran.

The strategic objective of Epic Fury is full counter-revolution, not peaceful reform and development.

Undermining diplomacy for (another) illegal war

Following joint military strikes by the United States and Israel on Iranian nuclear and military facilities on February 28, 2026, several countries officially urged the UN Security Council (UNSC) to convene for an emergency session.

France was the first council member to request a Security Council meeting. President Emmanuel Macron warned of “grave consequences for international peace and security”. Jointly Russia and China requested a briefing, characterizing the strikes as an “unprovoked and reckless act of military aggression.”

During the session, UN Secretary-General António Guterres condemned the escalation and called for an immediate ceasefire.

In the Global South, many leaders were shocked by the Trump administration’s disregard of Iranian life, severe violation of international law and Iran’s sovereignty, especially after US participation in Israel’s genocide in Gaza and its ongoing ethnic cleansing in the West Bank.

In historical view, none of this is new. Since the 1970s, US administrations have progressively opted for illegal wars and unilateralism at the expense of international law and multilateralism. What is new is that today all gloves are off. The deployment of brutal force is open, blatant and unapologetic. Since might is right, any criticism must be regarded as potential subversion.

Moreover, these strikes against Iran are not just about the Middle East. They are a prelude – a demonstration effect toward China/Taiwan and Russia/Ukraine theaters.

Overnight, the Trump administration, once again without an exit strategy, managed to drag the international community ever closer to a Cold War escalation.

It’s the oil (and gas), stupid

Iran was the fourth-largest crude oil producer in OPEC in 2023 and the third-largest dry natural gas producer in the world in 2022. What makes Tehran so attractive to the US is that Iran is the world’s third-largest oil and second-largest natural gas reserve holder.

In mid-January, when the American Petroleum Institute (API) gathered oil industry leaders and lobbyists for a summit, Bob McNally of the Rapidan Energy Group, a veteran industry insider, pushed hard for the overthrow of Iran’s leadership. “Iran holds the biggest promise,” McNally proclaimed. “If you can imagine our industry going back there, we would get a lot more oil, a lot sooner than we will out of Venezuela.”

During the first term of President George W. Bush, McNally served in the White House as Bush’s Special Assistant. In 2008, he served as Mitt Romney’s energy advisor; and in 2010, he advised Senator Marco Rubio. As Trump’s Secretary of State, Rubio has played a critical role in the ongoing regime change efforts in both Venezuela (world’s largest proven oil reserves) and Iran.

Despite its abundant reserves, Iran’s total liquids production is limited because the oil sector has been subject to under-investment and international sanctions for several years.

Efforts at external destabilization soared prior to US/Israeli strikes. On February 24, Damon Wilson, the head of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), revealed during a House oversight hearing that NED “began supporting the deployment and operation of about 200 Starlinks early on” amid the violence which swept through Iran last month. But he was abruptly interrupted by the ranking member of the House Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations, Rep. Lois Frankel, who told Wilson: “You know what, I’m going to interrupt you – we’d better not talk about it.”

In the US, mainstream media did not disclose the story. Only a few progressive outlets did. For its part, NED didn’t.

The war scenario

Here are the operational facts. The conflict started with the US/Israel-coordinated strikes, which hit nuclear, missile, and leadership targets across Iran. Expectedly, Iran retaliated with missiles and regional proxy attacks against Israel and US bases, including the Gulf states hosting U.S. military bases, such as Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar, Ali Al Salem in Kuwait, Al Dhafra in the UAE, and the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet in Bahrain.

Reportedly, the US/Israeli campaign had planned for weeks-long sustained operations. According to Israeli Defense Force, the joint attack consisted of over 200 fighter jets attacking 500 targets in the largest attack in Israeli Air Force history.

In Friday, early casualties (initial phase) featured 200+ killed in Iran, hundreds injured (initial estimates). Against US and Israeli assurances, civilian incidents have already been reported (e.g., school strike casualties).

These strikes will penalize global economic prospects, which are already constrained by geoeconomic fragmentation (sanctions blocs, supply-chain bifurcation), coupled with extremely high oil market sensitivity (Hormuz risk premium).

From the standpoint of the global economy, the US/Israel attack against Iran occurs amid elevated geoeconomic fragmentation. Second, the US military doctrine builds on a phased escalation ladder from coercion to paralysis to political outcome.

- Phase 1: Shock. Leadership targeting, nuclear/missile suppression and psychological dominance.

- Phase 2: System Paralysis. Aiming at air defense destruction, IRGC command disruption and economic isolation escalation.

- Phase 3: Political Outcome. With the strategic objective of internal collapse or negotiated capitulation.

The problem is that these military phases ensure no political resolution.

Trump’s four-week scenario

In the United States, President Trump has ducked reporters because the rationale for the US/Israeli Iran attacks – Iran’s planning for a preemptive attack against American interests – has proved untrue, as the US intelligence community has acknowledged.

In the Sunday interview with the British Daily Mail, President Trump disclosed a possible timeline for the war with Iran, suggesting fighting could go on for a month: “It’s always been a four-week process. We figured it will be four weeks or so. It’s always been about a four-week process so – as strong as it is, it’s a big country, it’ll take four weeks – or less.”

So, let’s model the 1-month scenario occurring against the backdrop of elevated geoeconomic fragmentation (not Cold War II). In this case, US strategy of phased escalation ladder is working imperfectly. As a result, the most realistic path is controlled escalation without regime collapse in Iran.

The scenario comes with new risks because in this scenario US and Israel seek to degrade Iranian strategic capacity enough to force a deterrence reset, while avoiding ground war. Iran responds asymmetrically but avoids actions that trigger US invasion. The likely outcome is military success, but political stalemate and economic shock in a very challenging historical moment.

Political turmoil, economic uncertainty, market volatility

In terms of duration, the US/Israeli attacks will use the first week to shock and demonstration, with precision strikes on nuclear infrastructure, IRGC bases, air defenses. Iran launches missile salvos toward Israel and US regional bases. Meanwhile, cyber operations expand both directions.

In political terms, there is an Iranian domestic rally-around-flag effect. Gulf states quietly support US, but call for de-escalation and hedge bets. In economic terms, oil jumps abruptly, with 20-30% risk premium and shipping insurance spikes in Gulf and Red Sea.

During the next 2-3 weeks, US/Israeli attacks seek to achieve system paralysis in Iran. If by then there is no tangible elite fracture inside Iran, the neutrality of the Global South increases and Western alliance cohesion begins to show trains, escalation risks compel the US and Israel on a diplomatic defensive. So, the fourth week will see negotiated stabilization pressure on both sides. The result could be an effective ceasefire without agreement.

But in economic terms, the unwarranted 1-month war would result in an energy shock, with oil price soaring to $115-140, gas prices rising via shipping risk and strategic reserves partially released. In shipping and trade, Red Sea and Gulf insurance premiums could double or triple, while delivery times lengthen due to inventory shocks.

The macro effect is elevated inflation as energy prices are coupled with rising costs in transport, food and manufacturing, central banks delaying the anticipated rate cuts and global growth decelerating. In financial markets, emerging markets would suffer from capital outflows. Civilian economies under-perform as defense and energy sectors outperform. Risk assets may not crash but will exhibit extraordinary volatility.

Escalation multiplies risks in the region and the world

Total deaths could soar to 15,000-35,000, a third or half of them civilian. The number of injured would surge to 60,000-120,000. Whereas the number of displaced persons could amount to 2-4 million.

Global inflation add-on could amount to 1-1.5 percentage points. Middle East GDP could suffer a -5-8% penalty and global growth prospects would be downgraded by -0.7%.

Like the Trump trade wars, it would produce no economic winners. But it could push the global economy closer toward an edge. It would be as unwarranted as the proxy wars in Ukraine, Gaza and elsewhere in the Middle East. And ultimately, civilians would pay the bill and defense contractors’ insiders would reap the profits.

The original version was published by Informed Comment (US) on March 2, 2026.

Stuck in Another Disastrous Middle East War

Unfortunately, President Trump listened to the neocons and Benjamin Netanyahu instead of his MAGA base and other voices of caution as he launched a surprise attack on Iran over the weekend. For the second time in nine months, the US Administration used negotiations with Iran as a cover to launch a pre-planned attack.

Last week’s talks produced “progress” according to all sides, with technical teams set to meet this week to work out the details. President Trump, however, suddenly announced that he was not happy with the talks because the Iranian side refused to say “the magic words” that they would not pursue nuclear weapons.

But Iran has been insisting for decades that they have no interest in producing a nuclear weapon and our own intelligence has confirmed that they are not doing so.

Shortly after President Trump’s announcement, the US and Israel launched their attack, killing Iran’s religious leader along with some 40 other political and military leaders in a “decapitation” strike.

It was supposed to be like the Venezuela operation. Quick and painless for the US. Kill the leadership and the long-suffering people would take to the streets and reclaim their country. It may make a good plot for a Hollywood movie, but in real life these regime change operations have never worked. Millions did take to the streets in Iran, but it was to mourn the slain Ayatollah and to reaffirm support for their government.

Just like we “rallied around the flag” after the attacks on 9/11.

Quickly, Iranian retaliation for the attacks began to take their toll on US assets and Israel. US soldiers have been killed and US fighter jets have been shot down. US bases in the region are either damaged or destroyed. Likewise, US embassies and consulates have come under attack, including by Iraqis likely still furious over the US destruction of their country 20 years ago.

And, with the Pentagon warning that the operation may go weeks instead of days, we are quickly running out of missiles.

Billions of dollars have already been spent on this unprovoked attack, and when the smoke clears – if it does – we may see hundreds of billions or maybe much more having been wasted on yet another Middle East war. Just what President Trump promised he would not do.

The neocon “cakewalk” crowd, including Lindsey Graham and others, have been proven wrong again. Tragically, more American servicemembers may die while the neocons blame someone else for the fiasco they helped launch.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said of the US/Israeli attack that “this combination of forces enables us to do what I have longed to do for 40 years…”

But the purpose of the US military is not to fulfill the decades-old wishes of foreign leaders. There is a good reason we have a Constitution that says only Congress can declare war.

Launching a military strike during negotiations will have lasting negative effects for the United States. Who would ever trust US diplomacy again if talks are used as a distraction for pre-planned attacks?

The Administration is doing its best to spin this unfolding disaster as all going according to plan, but what is the plan? No one knows. Do they know?

Here’s a plan: End this today. Return the destroyed US bases to the countries where they are located. And just come home. That is what a real “America first” movement looks like.

Ron Paul is a former Republican congressman from Texas. He was the 1988 Libertarian Party candidate for president.

Ron Paul is a former Republican congressman from Texas. He was the 1988 Libertarian Party candidate for president.