Calling Kamala Harris a Whore Won the Election for Trump

Photograph Source: Nathaniel St. Clair

I don’t know which is worse. The former Vice President’s defeat or the commentary that’s followed, monopolized by men of similar backgrounds.

Did German liberals appease the 3rd Reich as upscale liberals in our country are appeasing this American 4th Reich? Why do I call it the 4th Reich?

Members of the Trump administration, like Musk and Bannon, enjoy hoisting Nazi salutes, and Vice President Vance, on a trip to Germany, embraced the AfD, considered by some to be a Neo-Nazi party. He told German politicians they should “abandon their policy of maintaining a ‘firewall against the far right,’ a statement which received “murmurs from the audience and a backlash from German officials,” according to Jewish Chronicle, Feb.16, 2025.

New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof is the epitome of soppy upscale liberalism; he says Democrats shouldn’t talk down to the (white) working class, a charge against the Democrats that has been endlessly repeated. This line ignores the former president’s commitment to unions and that the former Vice President received the majority of votes from union households.

Kristof says that Democrats shouldn’t call Trump supporters racists and bigots. Millions of them are racists and bigots, and if they had succeeded in overthrowing the government on January 6th,, given the MAGA hostility towards The Times, he might find himself in an El Salvador prison where there ain’t no two hour five-star Manhattan lunches.

Like other Timesmen who believe that San Francisco is a scene from “The Last of Us,” he couldn’t resist taking a dump on San Francisco, defining the entire city by focusing on one section,which is how the president and his media buddies are defining Los Angeles. East Coast columnists know as much about San Francisco as we know about the ocean buried beneath the ice of Enceladus.

Kristof made his statement on May 28. On the same day, Robert Reich also attributed the former Vice President’s loss to economic discontent.

A serious study disposes of this theory. In January, political sociologist David N. Smith and his University of Kansas colleague, Associate Sociology Professor Eric A. Hanley, published a 47-page paper deconstructing the Republican president’s appeal. They write that “75% of Trump’s voters supported him enthusiastically, mainly because they shared his prejudices, not because they were hurting economically.” Sharing his prejudices means an intense paranoia about a DEI takeover led by Blacks, who are seen by the right as the group that puts other groups up to mischief.

It was left up to El Pais, a Spanish newspaper, to print my assessment of the election, where I wrote that the Vice President lost the election because of Racism and Misogyny. Trump got the locker room vote by defining the former Vice President in antebellum-old South terms as a promiscuous slave wench. It was his vile assertion that Kamela Harris achieved her status not by hard work but by using sex. He retweeted a post that the Vice President rose to power by giving blow jobs, which must have sent guffaws throughout the locker room. With this strategy, he got the locker room vote.

The present Vice President embellished Trump’s slander of the former Vice President when Vance referred to the then-Vice President as “trash.” Millions of white men believe that minority women are sluts who are available to them. That’s why Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the former head of the International Monetary Fund, believed that Nafissatou Diallo, a 33-year-old former housekeeper at the upmarket Sofitel hotel in Manhattan, was available to him for sexual assault. The good old boy Media of Manhattan took his side. They called her a whore. Strauss-Kahn, however, settled with Diallo for an undisclosed amount of money. Trump got the locker room, a locker room that holds millions of men. He reached back to the old antebellum South image of the Black woman as a promiscuous slave wench, the kind of lurid image of Black women one finds in the books of pro-slavery writers Thomas Nelson Page (In Ole Virginia) and Thomas Dixon (The Klansman) who represent the most shameful period in American literature.

to the then-Vice President as “trash.” Millions of white men believe that minority women are sluts who are available to them. That’s why Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the former head of the International Monetary Fund, believed that Nafissatou Diallo, a 33-year-old former housekeeper at the upmarket Sofitel hotel in Manhattan, was available to him for sexual assault. The good old boy Media of Manhattan took his side. They called her a whore. Strauss-Kahn, however, settled with Diallo for an undisclosed amount of money. Trump got the locker room, a locker room that holds millions of men. He reached back to the old antebellum South image of the Black woman as a promiscuous slave wench, the kind of lurid image of Black women one finds in the books of pro-slavery writers Thomas Nelson Page (In Ole Virginia) and Thomas Dixon (The Klansman) who represent the most shameful period in American literature.

Did Trump’s final argument during the campaign focus on economics? The price of eggs? No, as The Washington Post noted on October 29, 2024, “Donald Trump’s closing argument: Vulgarity” during a rally.

“Businessman Grant Cardone likened Vice President Kamala Harris to a prostitute. ‘Her and her pimp handlers will destroy our country,’ he said. “David Rem, billed as a childhood friend of Mr. Trump’s, called Ms. Harris the ‘‘Antichrist’ and ‘devil’ while waving a cross onstage. Elon Musk, who also spoke at Sunday’s rally, (in October 2024) posted on X, referred to Ms. Harris as the c-word. He opened a rally this month in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. Ms. Harris has been a “sh*t” vice president, and everything she touches turns to “sh*t.”

The Associated Press, October 27, 2025, reported that Trump called Democratic Vice-President Kamala Harris “the devil” and “likened the former California attorney general vying to become the first woman and Black woman president to a prostitute.”

A group called the “Speaking with American Men” project received twenty million dollars to study why young men didn’t vote for Kamala. I could have told Democrats for free why Kamala Harris lost.

The commentators didn’t recognize this ante bellum connection because they were educated to be copycat Anglos and have little knowledge of American history. Even TV’s official historians make omissions and mistakes.

The commentators continue to note that some Black and Latino men have abandoned the Democrats. Maybe Black and Hispanic men recoil at the thought of a woman president? Especially a woman of Indo-Black heritage with a Jewish husband, fodder for conspiracy theories.

Whites explained the alienation of Latino men from Democrats in economic terms. Victor Martinez, a Latino broadcaster and not one of the green room vagrants who are disproportionately white, said his Latino callers were opposed to a woman running things; the majority of Latina and Black women voted for Harris—Hispanic whisperer David M. Drucker failed to mention their vote when, appearing on “Morning Joe” on June 9, 2025, he explained why the Hispanic vote is trending right. Of course, some might have regrets. Some Cuban and Venezuelan Trump supporters have been threatened with deportation.

Sixteen rappers endorsed Trump as a nod to a fellow felon, including Curtis 50 Cents Jackson, who fronts for Starz network—a network which specializes in sleazy Black pathology dramas. Snoop Dogg performed at his inaugural. In an attempt to moderate the feud between Trump and Musk, Kanye West said he loved both of them.

Given that millions in Africa and the United States will die as a result of Trump’s policies, and Black and Brown women who will suffer the most from his abortion bans, the possible curtailment of Medicare and Social Security, the rappers’ endorsement of Trump has to be regarded as the biggest blunder in Black history. The headline of a story that appeared on the front page of The Times on June 19, 2025, read “Trump’s Cuts to South Africa Threaten Global Medical Progress.” On the editorial page was the statement: “Global malnutrition risks getting worse because of Trump’s cuts in humanitarian aid.”

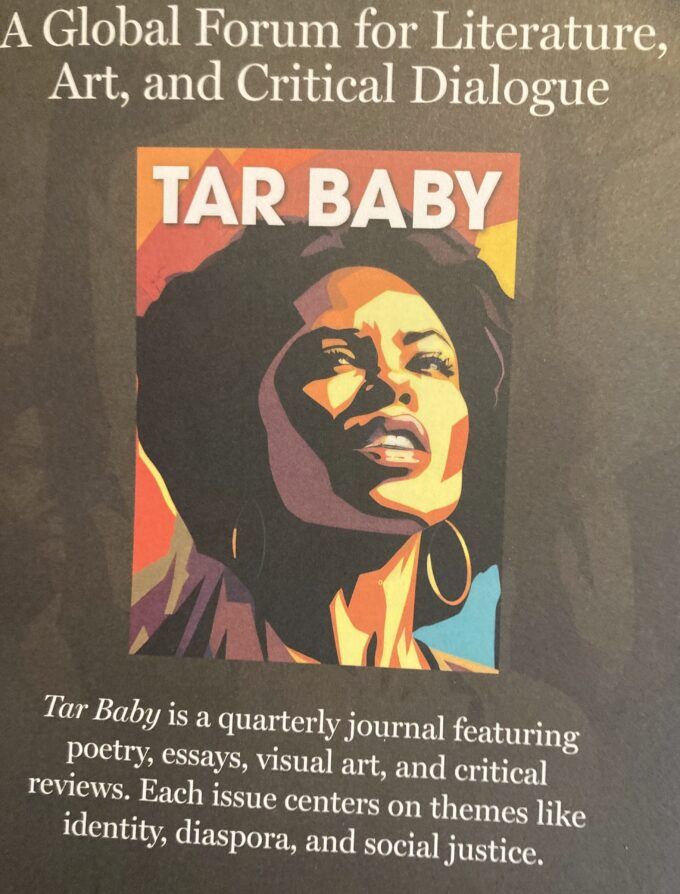

In my interview with Don Lemon for Tar Baby magazine, for which I am editor-in-chief, he discounted the influence of rappers. I disagree. These rappers have millions of followers.

How did white women react to these lewd lowlife attacks against their sister? The majority voted for Trump for the third time. Maybe they admire Trump’s antebellum style. In the old South, White men ruled women and minorities. Perhaps they suffer from the political version of the Stockholm Syndrome.

There’s a scene in James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans where a Native American voices his objection to a white settler as a lookout for an encampment because he might misinterpret some signals. He might confuse the noise of the enemy with that of an animal.

This is the problem with an American commentariat that lacks diversity. There are signs that they miss.

Progressives had issues with Kamala Harris, mostly having to do with her stance on the genocide in Gaza. Like Hubert Humphrey, who lost to Richard Nixon because he could not stray from President Johnson’s position on Vietnam, she was compromised because of her loyalty to President Biden. (Forgotten is a statement attributed to Humphrey, when discussing poor living conditions in urban ghettos. Humphrey stated: “I’ve got enough spark in me to lead a mighty good revolt under those conditions….”) But even with her equivocating about Gaza, where daily war crimes are committed, progressives should have expressed more outrage about the nasty treatment of this woman by white men like Trump and Vance, who view all Black women as “trash,” loose and available.

In October, Ishmael Reed’s play “Life Among the Aryans” which predicted the Insurrection, will have a repeat performance at the Black Rep. Group.

BEFORE ILLUMINATUS THERE WAS MUMBO JUMBO

LA REVUE GAUCHE - Left Comment: Search results for ISHMAEL REED

LA REVUE GAUCHE - Left Comment: Search results for MUMBO JUMBO