This planned investigation, titled Philadelphia and The Darkside of Liberty, is a deliberate examination into the cultural, economic, and sociopolitical foundations which undergirded America’s early colony and its newly birthed land of liberty’s class-stratified slave society – combined with a closer look at the contradictions which laid within the notions and/or paradoxes of early American equality, freedom, race, and enslavement (commencing in the seventeenth-century). This proposed study therefore will contend that to appreciate the early interpretations of American political organization, it is essential to understand its beginnings – centering on the U.S. Constitution. This review will initially focus principally (however not exclusively) on the distinct influences of important personages such as James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Gouverneur Morris, and others – imbued within early American thought and thus influenced by renowned Enlightenment thinkers such as John Locke, David Hume and Adam Smith – exemplified and exhibited in the celebrated Federalist Papers, with a specific and detailed focus on No.10;[1] additionally including Jefferson’s Notes on Virginia,[2] which will help to outline and undergird the key arguments put forth by this study.

Many of those notables that assembled in the city of Philadelphia in that historic year of 1787 were intent on framing a resilient centralized government that stood in accordance with Adam Smith’s essential maxims which affirmed that “Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defense of the rich against the poor, or of those who have some property against those who have none at all;” contending that civil government, “grows up with the acquisition of valuable property.”[3] Consequently, this analysis will challenge that long-held notion which has described early American thought and society as “egalitarian, free from [the] extreme want and wealth that characterized Europe.”[4] In fact, as will be demonstrated throughout the work that follows, by an array of noted scholars and academics, this exploration will prove that property, class, and status played a significant, although perhaps not an exclusive, role in the development of that early colony and its nascent nation.

The intricacies of these contradictions will be examined in further detail throughout this study, arguing that, it is impossible to elude the fact that status, class, and race performed a major part in the views and doctrines woven within the principles and legal mechanisms formulated by those luminaries in that early republic. In fact, the following quote extracted from a letter written in 1786 by a French diplomat (positioned as the chargé d’affaires), in communiqué with his government, leading up to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, helps to delineate the top-down attitudes and devices engineered by the men historically known as the “Framers:”

Although there are no nobles in America, there is a class of men denominated “gentlemen.” … Almost all of them dread the efforts of the people to despoil them of their possessions, and, moreover, they are creditors, and therefore interested in strengthening the government and watching over the execution of the law…. The majority of them being merchants, it is for their interest to establish the credit of the United States in Europe on a solid foundation by the exact payment of debts, and to grant to Congress powers extensive enough to compel the people to contribute for this purpose.[5]

As supported, evidenced, and argued by famed bottom-up historians like Michael Parenti, Charles A. Beard, Michael J. Klarman and others, the concepts of class and ownership and their European legacy greatly contributed to the initial composition of that early American dominion and its proprietorship stratum. In fact, as Professor Parenti demonstrates, “from colonial times onward, ‘men of influence’ received vast land grants from the [English] crown and presided over estates that bespoke an impressive munificence.” Parenti also reveals the stark differentials woven within the colonial class structure through exposing the fact that, “By 1700, three-fourths of the acreage in New York belonged to fewer than a dozen persons.” And, beyond that, “In the interior of Virginia, seven individuals owned 1.7 million acres,” exhibiting a structuralized formulation of wealth concentration from early on. In the run-up to the American Revolution, some twenty-seven years prior to the Continental Congress taking place in that celebrated year of 1787, Professor Parenti additionally notes that, “By 1760, [some] fewer than five hundred men in five colonial cities controlled most of the commerce, shipping, banking, mining, and manufacturing on the eastern seaboard.” Again, Parenti brings to the fore, a clear demarcation between the few and the many, property ownership and capital accumulation in that newly formed land of “equality,” which will be explored and surveyed in further detail within this work.[6]

Chapter One of this dissertation will do a deep dive, in part, by focusing on documentary evidence penned by the “Framers” themselves. In addition to that, this work will seek to challenge existing historiographical debates, as noted, by displaying both the negative and positive legacy left by the men that articulated the U.S. Constitution in the city of Philadelphia in that momentous year of 1787. Furthermore, a major theoretical element of this retrospective will be working with, and challenging, the classifications and clashes within the so-called American ideals of Independence, Liberty, and Equality through studying an array of viewpoints from historical masterworks by Gordon S. Wood, Woody Holton, and others as mentioned below. Some of the topics brought forth within this research will include Chapter One, “An American Paradox: The Marriage of Liberty, Slavery and Freedom.” Chapter Two, “Cui Bono – Who Benefitted Most from the Categorical Constructs of Race and Class in Early America?” And, finally, in Chapter Three, this work will take a cogent look at “The Atomization of the Powerless and the Sins of Democracy,” historically from antiquity and beyond, by reflecting upon the judgments, attitudes and viewpoints, from a class perspective, of the privileged faction of men that forged that early nation’s crucial founding doctrines and documents. Again, these chapters above mentioned will take a thorough look at the varying constructs of race and class throughout the American experience from the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and early part of the Twentieth centuries, focusing on cui bono, that is, who benefitted most from those racialized constructs of division and how those benefits negatively affected those societies at large socially, politically, and culturally.

Specifically, the chapters summarized above will bring together the importance of understanding just how class, ownership, and status, per race, position, and wealth demarcated the early American experience within governmental and societal structures, rules, and regulations from 1787 forward – surveying the uniqueness of the U.S. Constitution (both pro and con) along with its Amendments (known as the Bill of Rights) will help provide a nuanced understanding of both said document and the men that formulated it. Which later impacted social movements and social discord from abolitionism to civil rights. This study will deliver not just a structuralized economic and political viewpoint, but a humanistic perspective. Moreover, this research will incorporate historical and scientific classics by such noted scholars as Edmund S. Morgan, Edward E. Baptist, Barbara J. Fields; and Nancy Isenberg – just to name a few. The foundations of racial divisions mentioned above were clearly measured by 16th-century English theorist and statesman Francis Bacon when he penned, “The Idols of the Tribe have their foundation in human nature itself, and in the tribe or race of men.”[7] As determined, Bacon defined racism as an innate element of human nature. Hence, this study will challenge that hypothesis, in part, by arguing that divisions of race within the human condition are social constructs that ultimately benefit those that exercise those dictates.

1

The Paradox of Early American Freedom

What were the underlying moral and ideological contradictions woven within that newly birthed land of freedom’s class-stratified slave society?

We believe we understand what class is, that being, an economic social division shaped by affluence and privilege versus want and neglect. “The problem is that popular American history is most commonly told, [or] dramatized, without much reference to the existence of social classes.” The story, in the main, is taught and/or conveyed as a tale of American exceptionalism – as if the early American colonies, and their break with Great Britain, somehow miraculously transformed the constraints of class structuralism – resulting in a greater realization of “enriched possibility.” This conception of America was galvanized by the men that formulated its constitution in the city of Philadelphia in that momentous year of 1787 with great elegance – an image of how a modern nation “might prove itself revolutionary in terms of social mobility in a world traditionally dominated by monarchy and fixed aristocracy.” America’s most beloved myths are at once encouraging and devastating: “All men are created equal,”[8] for example, which excluded Indigenous Peoples and African Americans, penned by renowned American statesman and philosopher Thomas Jefferson in his landmark Declaration of Independence written in 1776 – was effectively employed as a maxim to delineate, as historian Nancy Isenberg presents, “the promise of America’s open spaces and united people’s moral self-regard in distinguishing themselves from a host of hopeless societies abroad,” but the tale is much darker, more troublesome and abundantly more nuanced than that.[9]

An elite colonial land-grabbing class, from early on, in that fledgling America, contrived its own attitudes and perspectives – those which served it best. After settlement, starting as early as the seventeenth century, colonial outposts exploited their unfree labor: European indentured servants, African slaves, Native Americans, and their offspring – describing such expendable classes as “human waste.”[10] When it comes to an early settler-colonial mentality of not only conquest but profitability as an exemplar, “Coined land,” is the term that Benjamin Franklin (noted Eighteenth Century political philosopher, scientist, and diplomat) used to refer to, or celebrate, the intrinsic monetary value woven within the then brutal land acquisition and/or theft from the Indigenous Native American population at the time – appropriated land which was later “privatized and commodified” in the hands of venture capitalists, described as “European colonists.”[11] These attitudes of hierarchy over “the people out of doors,” as those eminent luminaries that gathered in Philadelphia later referred to them were long held. A phrase, according to noted Professor of History Benjamin Irvin, that was largely defined to incorporate not only “the working poor” that clamored in the streets of Philadelphia during the Convention of 1787, but all peoples who were disenfranchised by that newly formed Continental Congress, “including women, Native Americans, African Americans, and the working poor.”[12] In fact, as Isenberg demonstrates, notions of superiority from the upper crust of that early society toward, “The poor, [or waste people], did not disappear, [on the contrary], by the early eighteenth century they [the lower classes] were seen as a permanent breed.”[13] That is, a taxonomical classification viewed through how one physically appeared, grounded in their class and conduct, came to the fore; and, this prejudicial manner of classifying and/or categorizing bottom-up human struggle or failure took hold in the United States for centuries to come – which will be further explored within subsequent chapters.

These unfavorable top-down class attitudes toward the poor or “waste people” emanated from what was known at the time as the mother country, that is, England itself – where as early as the 1500s and 1600s, America was not viewed as an “Eden of opportunity,” but rather a “giant rubbish heap,” that could be converted and cultivated into productive estates, on behalf of wealthy landowners through the unloading of England’s poor and destitute – who would be used to develop that far-off wasteland. Again, as Isenberg contends, “the idle poor [or] dregs of society, were to be sent thither simply to throw down manure and die in a vacuous muck.” That is, before it became celebrated as the fabled “City on a Hill,”[14] auspiciously described by John Winthrop (English Puritan lawyer and then governor), in his well-known sermon of 1630, to what was then the early settlement of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, “America was [seen] in the eyes of sixteenth-century adventurers [and English elites alike] as a foul, weedy wilderness – a ‘sink-hole’ [perfectly] suited to [work, profit and lord over] ‘ill-bred commoners,’”[15] clearly defining top-down class distinctions from early on.

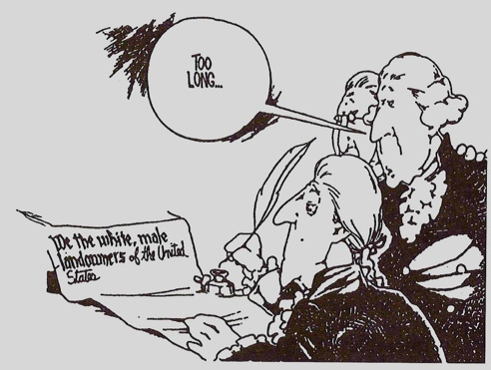

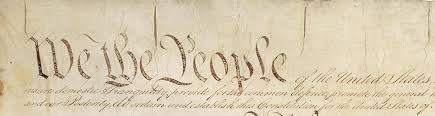

Returning to those eminent American men that later devised the doctrines and documents which conceived of a “new nation” built on individual liberty and freedom, under further examination, begs the question: “Freedom for whom and for what?” This study will delve deeper into who those men were and how their overall attitudes toward the general populous as far as class, education, rank, and proprietorship, eventually led to a decisive result known as the U.S. Constitution. To appreciate the U.S. political and economic structure, it is essential to understand its original formulation, starting with said constitution. Those dignitaries that gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 were intent on framing a strong centralized government in adherence with (what they believed to be Scottish economist and theorist) Adam Smith’s fundamental dicta and/or revelations, which stated that government was “instituted for the defense of the rich against the poor” and “grows up with the acquisition of valuable property.”[16] As Political Scientist and author, Robert Ovetz argues below, the mechanisms and/or devices designed and implemented within the U.S. Constitution were contrived from the outset to thwart any and all democratic control. Equally noted, the Framers’ brilliance was in formulating a virtually unalterable system which offered through clever slogans like “We the People” an assurance of participation within the constructs of a Republic, all the while permitting “a few to hand-pick some representatives,” whilst the majority thus surrendered “the power of self-governance.” The U.S., still to this day, lauds itself as a “Democracy,” yet, from the outset, as argued, that illustrious landmark charter mentioned was nefariously intended to “impede democratic control of government” all the while foiling “democratic control of the economy.”[17]

Under careful observation, no section of the U.S. Constitution is more misconstrued and misinterpreted than its Preamble. Moreover, the term, “We the People,” for example was, and still is to this day, deliberately employed as a rhetorical device in the form of a “philosophical aspiration,” separating it from the dry legalese that compose most of the rest of the charter. This, perhaps, is why the Preamble . has grasped the attention of the common everyday citizen. It embodies the hopes and values of ordinary people, cunningly expressing what they would ideally like the Constitution to achieve in practice – even though in truth it does something distinctively different. In fact, if we survey the meaning of the doctrines found within the Preamble, we find a set of material relations dating back to the 1700s which were brilliantly devised to deliberately constrain economic and political democracy:[18]

Figure 1: The original handwritten Preamble to the U.S. Constitution on permanent display at the National Archives.

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.[19]

The “Blessings of Liberty” run amiss. Again, those “Framers,” or group of elite men that gathered in Philadelphia for that historic event in 1787 ideally utilized the inclusive language of “We the People,” . while at the same time, implementing a complex structural formulation which would stave off the will of the common people at every turn. The fifty-five of the seventy-four delegates that showed up on the scene, were, in fact, a cohort indistinguishable from themselves as “wealthy white men” of whom only a small number were not rich (but nevertheless affluent). They viewed themselves as “the People,” who would not only be provided liberties under that newly devised constitution, but also offered themselves the power to control the authority within that newly formed centralized government.[20]

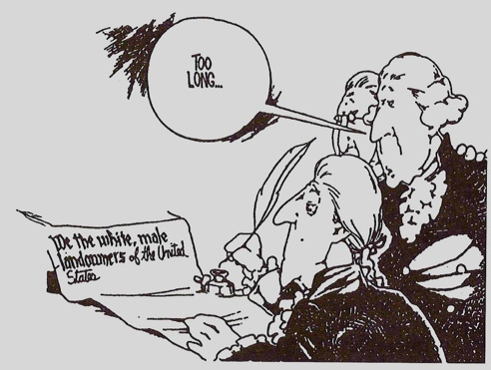

Figure 2: The Framers working out the concept of “We the People” by Tom Meyer.

By bringing the term “insure domestic Tranquility” to the fore, an early American top-down class paradigm is made evident by those men of property historically known as the “Framers.” The U.S. Constitution was the result of the repercussions of the American Revolution and decades of class conflict from within. Cogent warnings provided by not only Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence,[21] which cautioned against “convulsions within” and “exciting domestic insurrections amongst us,” but also forewarnings offered by the man considered “the father of that newly formed nation,” George Washington. In the following statements to the run-up of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, written in correspondence to his then erstwhile comrade-in-arms and chief of artillery, General Henry Knox, George Washington (supreme commander of the American revolutionary colonial forces and hero par excellence) projected clear class distinctions, fears and/or biases which lie at the heart of this study, “There are combustibles in every state, to which a spark might set fire.”[22] Hence, as Professor of Law, Jennifer Nedelsky asserts, what General Washington believed was necessary was a statutory formulation of control, instituted and devised by the upper crust of society, in the shape of a constitution, “to contain the threat of the people rather than to embrace their participation and their competence,”[23] or else, as stated in a second letter to Knox, the eminent General warned, “If government shrinks, or is unable to enforce its laws … anarchy & confusion must prevail – and every thing will be turned topsy turvey,”[24] demonstrating an elite fear most pronounced.

Figure 3: George Washington (1732-1799), Supreme Commander of the American Revolution and First President of the United States.

A good exemplar of a “spark that set fire,” which struck fear in the hearts of that elite class of men assembled in Philadelphia, is famously known as Shays’ Rebellion (August 29, 1786 to February 1787), led by former American army officer and son of Irish Immigrants, Daniel Shays, which culminated in a bottom-up armed revolt that took place in Western Massachusetts and Worcester, in response to a debt crisis imposed upon, in large part, the common citizenry; and, in opposition to the state government’s increased efforts to collect taxes on both individuals and their trades – as a remediation for outstanding war debt. The rebellion was eventually put down by Colonial Army forces sent there by George Washington himself – staving off the voice of the people, in that newly formed land of liberty. What “Tranquility” actually meant, as established by the Framers, was a centralized government formulated within the constitution, with the ability to halt and/or suppress conflict or unrest that threatened “the established order and governance of the elite.”[25] Shays’ Rebellion in combination with the possibility of slave uprisings and native resistance offered the justification for creating, and later expanding, a domestic military force as penned into the Charter by Gouverneur Morris (1752 – 1816), American political leader and contributor to the Preamble outlined above. Morris cleverly emphasized the necessity for a general fiscal “contribution to the common defense” on behalf of his class interests, warning of the possible dangers of both “internal insurrections and external invasions” as outlined in detail in Article I Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution.[26] In summary, by centralizing a military power within a national charter, “the elites got their own protection force against the possibility of the majority’s ‘popular despotism’” as described by Washington himself – thwarting any and all popular resistance to elite rule. In fact, by 1791, just four years after the Constitutional Congress met in the city of Philadelphia, that newly formed nation’s military force tripled its cost and increased its number of troops by fivefold.[27]

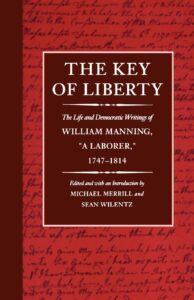

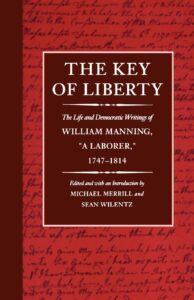

Figure 4: The Key of Liberty: The Life and Democratic Writings of William Manning, “a Laborer,” 1747–1814In challenging that ideal of promoting “the general Welfare,” within a class paradigm, William Manning, (1747 – 1814) American Revolutionary soldier, farmer, and novelist, was one of the few voices at the Constitutional Convention that stood up and pushed back against the elite coup that was evidently taking place. After having fought in the Revolutionary War, as a common foot soldier, he began to believe that his military service and sacrifice carried little weight with the elites that surrounded him. He also delineated the fact that those measures which reflected Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, and (the first President of the Continental Congress) John Jay’s views, and policies, created a poisonous atmosphere, ideology, and division between the “Few and the Many.” William Manning feared that by locking “the people out of doors,” out of government, the Founders were implementing measures such as Hamilton’s economic vision for that newly formed nation “at the expense of the common farmer and laborer.”[28] When it came to Shays’ Rebellion, for example, his views were commensurate with those of the uprising, but not with their methods of armed resistance. Based on his staunch democratic values, he called upon the common man to forcefully use new organizational tactics by directly petitioning the government to redress grievances. Manning understood the economic divisions as implemented.[29] In 1798, he authored his most celebrated work, The Key of Liberty, in which he displayed what he believed to be the objectives of the “Few” – which were to “distress and force the Many” into being financially dependent on them, “generating a sustained cycle of dependence.” Manning argued that the only chance for the “Many” was to choose those leaders that would battle for those with lesser economic and political authority.[30] What Manning understood so well was that those early colonial financial interests defined their own class “influence and benefits” as “the general Welfare” which was, in his view, in diametrical opposition to much of the population.

Figure 5: Alexander Hamilton (1757-1804), the First Secretary of the Treasury from 1789 to 1795 during George Washington’s presidency.

Alexander Hamilton’s celebrated financial plan alluded to above, put that early nation on a trajectory of economic growth, through a concentration of wealth in the form of property and holdings which would serve his class best, “…so capital [as] a resource remains untouched.”[31] Hamilton delivered an innovative and audacious scheme in both his First and Second Reports on the Further Provision Necessary for Establishing Public Credit issued on 13 December 1790. Again, on behalf of his class interests, that newly devised federal government would purchase all state arrears at full cost – using its general tax base. Hamilton understood that such an act would considerably augment the legitimacy of that newly formed centralized government. To raise money to pay off its debts, the government would issue security bonds to rich landowners and wealthy stakeholders who could afford them, providing huge profits for those invested when the time arrived for that recently formed Federal government to pay off its debts.[32] Charles Beard, Columbia University historian and author, in his famed book, An Economic Interpretation of The Constitution of The United States, succinctly outlines Hamilton’s class bias woven within his strategy per taxation, “[d]irect taxes may be laid, but resort to this form of taxation is rendered practically impossible, save on extraordinary occasions, by the provision that ‘they [taxes] must be apportioned according to population’ – so that numbers cannot transfer the burden to accumulated wealth”[33] – revealing a significant economic top-down class preference and formulation of control from the outset. Beard summarizes as such, “The Constitution was essentially an economic document based upon the concept that the fundamental private rights of property are anterior to government and morally beyond the reach of popular majorities.”[34] Given the United States’ long history of top-down class biases and bottom-up class struggle, to be further explored within this research, Beard provides a cogent groundwork.

Figure 6: James Madison (1751-1836), Father of the U.S. Constitution and Fourth President of the United States.

James Madison, elite intellectual and Statesman, was and is traditionally proclaimed as the “Father of the Constitution” for his crucial role in planning and fostering the Constitution of the United States and later its Bill of Rights. For many of the Framers, with Madison in the lead, the Articles of Confederation (previously formulated on November 15, 1777, and effectuated on March 1, 1781) were a nefarious compact among the 13 states of the United States, previously the Thirteen Colonies of Great Britain, which operated as the nation’s first framework of government establishing each individual State as “Free and Independent” – eloquently encouraged and outlined in Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence.[35] From a class vantage point, the phrase “establish Justice” as devised by Madison within the Preamble above, meant in an idealistic sense, that the government would apply the rule of law impartially and consistently to all, irrespective of one’s station in society. But, in fact, the expression, “establish Justice,” explicitly points to the Framers’ “intent to tip the balance of power back in favor of the elites.”[36] Notably, by early 1783, in his famed “Notes on Debates in Congress Memo” dated January 28th, 1783, some four years prior to the ratification of the U.S. Constitution on December 12th, 1787, Madison had well-defined what “justice” had meant to him and his cohorts by asserting that, “the establishment of permanent & adequate funds [in the form of a general taxation] to operate … throughout the U. States is indispensably necessary for doing complete justice to the Creditors of the U.S., for restoring public credit, & for providing for the future exigencies of … war.”[37] For Madison, as argued by eminent Professor of History Woody Holton, “establishing Justice” envisioned doing what some of the States were reluctant and/or incapable of achieving – that being, the payment of debts for the elites by “safeguarding their property” whether it be slave, land, or financial.[38]

How class and race maintained supremacy. In essence, the cleverly devised Three-fifths Compromise outlined in Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution, conceived by Madison, not only preserved, and reinforced the atrocity of slavery, but it also made stronger “the power of property” produced by the capitalization of all human labor. The minority checks embedded in the constitutional power of taxation ultimately prevented all types of what the Framers referred to as “leveling,” that being a fair and equal redistribution of wealth and resources amongst the general population.[39] In doing so, the constitution serves in perpetuity to protect wealth from what the Framers feared most: “economic democracy.”[40] Unambiguously, the Three-fifths clause established that three out of every five enslaved persons were counted, on behalf of their owners, when deciding a state’s total populace per representation and legislation. Hence, before the Civil War, the Three-fifths clause gave disproportionate weight to slave states, specifically slave ownership, in the House of Representatives.

A final element written within the Preamble of the U.S. Constitution worth further mention is the famed idiom “secure the Blessings of Liberty to Ourselves and Our Posterity,” a phrase that concisely encompasses the opinions of that band of elites, that amassed in Philadelphia, known as “the Framers” and their historical and material view of the possession of “Private Property” – greatly influenced and inspired by English Enlightenment philosopher and physician John Locke (1632-1704). Locke, in his famed The Two Treatises of Civil Government, argued that the law of nature obliged all human beings not to harm “the life, the liberty, health, limb, or goods of another,” defined as “Natural Rights.”[41] As a result, the Framers (most of whom were large landowners) were intent on designing a centralized government that would singularly protect and defend “private property.” The U.S. Constitution fosters this by placing a collection of roadblocks and/or obstacles in the way of majority demands for “economic democracy” – what, on numerous occasions, James Madison himself described as an oppression, enslavement and/or tyranny of the majority.[42] In a land without Nobles, Madison declared that “the Senate ought to come from, and represent, the wealth of the nation.”[43] With Madison’s compatriot John Dickinson of Delaware in full accord, proclaiming that the Senate should be comprised of those that are, “distinguished for their rank in life and their weight of property, and bearing as strong a likeness to the British House of Lords as possible.”[44] Additionally, Pierce Butler, wealthy land-owning South Carolinian, stood in complete agreement confirming that the Senate was, “the aristocratic part of our government.”[45] Those elite men, as members of that continental congress, largely on their own behalf, cleverly formulated “a plethora of opportunities to issue a minority veto of any changes by law, regulation, or court rulings,” that might menace their property ownership.[46] In essence, that charter known as the U.S. Constitution was brilliantly constructed to ensure an elite control and privilege that would last for “Posterity” – forever unchanged and unchangeable.

There is a wealth of evidence, as demonstrated, that the U.S. Constitution was originally designed and implemented not to facilitate meaningful bottom-up systemic change, but to ultimately avert anything that does not serve the benefits of the propertied class. Let us keep in mind that meaningful change from below has always been hard-fought, but not impossible. It took roughly seventy-eight years from 1787; and, a Civil War which lasted from 1861 to 1865, culminating in the loss of nearly 620,000 lives to officially abolish slavery under Amendment XIII (ratified on December 6th, 1865).[47] Until then, human bondage was a long held and integral form of property ownership within the United States – to be further examined within this work. Reflecting succinctly on the underlying class interests during and prior to the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, two indispensable statements, concerning “human nature,” from two essential minds, per class, which undergird the views here summarized, are as follows: Benjamin Franklin keenly observed that any assemblage of men, no matter how gifted, bring with them “all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interest and their selfish views.”[48] Which stood ironically in accordance with Adam Smith’s, “All for ourselves, and nothing for other people, seems, in every age of the world, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind,”[49] which demonstrates Smith’s historical view per an innate class perspective of wealth concentration.

2

Cui Bono – Who Benefitted Most from the Categorical Constructs of Race and Class?

The year 1776 is a deceptive starting point when it comes to the ideologies of American freedom and liberty. Independence from Great Britain did not expunge the British class arrangement long embraced by colonial elites that undergirded a social system of division which promulgated “entrenched beliefs about poverty and the willful exploitation of human labor.” An unfavored view of African slaves and poor whites widely thought of as “waste and/or rubbish,” remained a long-held social construct which served American elites well into the modern era.[50] From the outset, when it came to class dynamics, no one understood the manipulative power of faction and discord sown amongst the masses better than James Madison himself as boldly outlined in Federalist #10. The danger, Madison argued on behalf of his class interests, was not faction itself, but the escalation of “a majority faction” grounded in that “most common and durable source” of conflict: the “unequal distribution of property.”[51] In that widely celebrated land of “democracy,” Madison revealed not only his class biases anathema to the concept, but his fear of the very idea: “When a majority is included in a faction,” it could use democracy, “to sacrifice to its ruling passion or interest the public good and the rights of other citizens” – that is, the privileges of the propertied class.[52] To his credit, from early on, James Madison laid out clear class distinctions, partialities, and fears woven within that newly formulated American social stratum – which are essential to this study. Within Federalist #10, Madison brilliantly devised a strategy of division which would protect elite interests by suppressing the economic menace of a majoritarian class faction through the encouragement of as many divisions within the populous as possible. Hence, as he outlined, the “greater variety of parties and interests [within class, race, gender, or religion] … make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have common motive.”[53] Ironically, faction was problematic as stated, yet, at the same time, paradoxically, according to James Madison, more of it was the answer.

From the outset of the American experience, as outlined in his masterwork, American Slavery, American Freedom, Edmond S. Morgan, Yale Professor of History, makes evident the elite class interests and/or dynamics that fortified the use of clever rhetorical devices, such as “freedom and liberty” upon the general populous – all the while devilishly using the cruelty of slavery as a unifying force. During his visit to that early America, an astute English diplomat by the name of Sir Augustus John Foster, serving in Washington during Jefferson’s presidency (1801-1809), keenly observed, “[Elite] Virginians above all, seem committed to reducing all [white] men to an equal footing.” Foster observed, “owners of slaves, among themselves, are all for keeping down every kind of superiority”; and he recognized this pretension of equality used upon the masses as a powerful manipulative tactic. Virginians, he argued, “can profess an unbounded love of liberty and of democracy in consequence of the mass of the people, who in other countries might become mobs, being there nearly altogether composed of their own Negro slaves….”[54] In that ruthless slave society, as Morgan reveals, “Slaves did not become leveling mobs, because their owners would see to it that they had no chance to. The apostrophes to equality were not addressed to them.”[55] In clarification, he adds:

…because Virginia’s labor force was composed mainly of slaves, who had been isolated by race and removed from the political equation, the remaining free [white] laborers and tenant farmers were too few in number to constitute a serious threat to the superiority of the [elite white] men who assured them of their equality.[56]

The ancient Roman concept of Divide and Conquer, which dates to Julius Caesar himself, was effectively implemented by Virginia’s elite propertied class through the skillful use of cooptation. Virginia’s yeoman class comprised of small land-owning farmers were made to believe that they shared “a common identity” with those “men of better sorts,” simply due to the fact that neither was a slave – hence, both were alike in not being slaves.[57] Ironically, in the mindset of those early American elites that viewed themselves as the founders of a republic, largely inspired by Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth and the pushing off of monarchy, slavery occupied a critical, if not indeterminate position: it was thought of as a principal evil which free men sought to avoid for society in general through the usurpation of monarchies and the establishment of republics. But, at the same time, it was also viewed as the solution to one of society’s most pressing problems, “the problem of the poor.” Elite Virginians could move beyond English republicanism, “partly because they had solved the problem: they achieved a society in which most of the poor were enslaved.”[58] In truth, contempt for the poor permeated the age. John Locke, English philosopher and physician (1632-1704), considered one of the most essential of Enlightenment thinkers, commonly read, discussed, and admired by early American elites, famously wrote a classic defense of the right of revolution in his Two Treatises of Civil Government published in 1689 – yet he did not extend that right to the poor. [59] In fact, in his proposals for workhouses and/or “working schools,” outlined in his Essay on the Poor Law, published in 1687, the children of the [English] poor would “learn labor,” and nothing but labor, from a very young age, stopping short of enslavement – though it would require a certain alteration of mind to recognize the distinction.[60] That said, those astute men that assembled in the city of Philadelphia in 1787 took their inspiration from Locke very seriously.

Hamilton and Madison were in absolute accord with Locke’s views per property and ownership, that being, “Government has no other end but the preservation of property.”[61] Consequently, the U.S. Constitution was designed to both govern the population through limiting its capacity to self-govern; and by protecting all forms of property ownership including the enslavement of human beings. Hence, as historian David Waldstreicher (expert in early American political and cultural history) presents, the Constitution was devised not only to safeguard slavery as a separate economic system, but as integral to the basic right of what he describes as the “power over other people and property (including people who were property).”[62] As a result, the tensions and/or rivalries that resided in that newly formed nation, which would eventually lead to a bloody Civil War, were not over quantities of land possession between the North and the South, but more focused on how many slaves resided in each. To his credit, Madison presciently admitted as such:

[T]he States were divided into different interests not by their difference of size … but principally from the effects of their having or not having slaves. These two causes concurred in forming the great division of interests in the U. States. It did not lie between the large & small States: It lay between the Northern & Southern.[63]

Slavery was considered insidious by some, and yet fundamental to those that profited from it, both North and South. In fact, John Rutledge, esteemed Governor of South Carolina during the Revolution; and delegate to the Constitutional Convention, spoke on behalf of the Southern planters’ class by supporting slavery, of which, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney also of South Carolina, stood in full agreement. Both men implored their fellow delegates to recognize their common interests in preserving slavery from which they “stood to profit,” not only from selling slave-produced goods, but from carrying the slaves on their ships[64] – hence, they argued, stood a long-held alliance between Northern “personality” (that is, financial holdings) and “that particular form of property” (slavery) which dominated the South.[65] Slaves were long held the most valuable asset in the country. By 1860, the total value of all the slaves in America was estimated at the equivalent of $4 billion, more than double the value of the South’s entire farmland valued at $1.92 billion, four times the total currency in circulation at $435.4 million, and twenty times the value of all the precious metals (gold and silver) then in circulation at $228.3 million.[66] Thus, at the time and thereafter, North American slavery was not just a national or sectional asset, but a global one. As a result of the promise of monetary benefits and values produced by enslaved peoples, “the Framers,” in defense of their own interests, collectively devised a system of fail-safe mechanisms to protect their most cherished resource: human vassalage.[67] Moreover, in addition to the Three-Fifths Clause described above, the Constitution contained several safeguards with a clear objective of maintaining the vile system as it was. The Foreign Slave Trade Clause as outlined in Article 1; Section 9 of that charter known as the U.S. Constitution stated that Congress could not prohibit the “importation of persons” prior to 1808 – which cleverly excluded the term “slave.”[68] The intention of said clause, was not to stave off slavery, but was implemented to maintain, if not inflate, the monetary value of those persons already in captivity – when it came to their sale and transport to other slave states outside of Virginia. The Fugitive Slave Clause as written in Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3, was clearly devised to protect elite proprietorship over individuals forcefully ensconced in a system of chattel slavery:

No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.[69]

This Clause, not nullified until the Thirteenth Amendment’s abolition of slavery, considered it “a right” on the part of a slaveholder, to retrieve an enslaved individual who had fled to another state. Finally, as esteemed University of Chicago Professor, Paul Finkelman, contends, the ban on congressional export taxes adamantly argued for by those elite men that gather in Philadelphia, was, for the most part, a concession to southern planters whose slaves primarily produced agricultural goods for export.[70] Clearly demonstrating and demarcating an upper-class bias based on ownership, race, and wealth from the outset.

How elite capture worked in early America – diversity was implemented and utilized as a ruling class ideology. Privileged landowners, specifically Virginians, being “men of letters,” as they would have thought of themselves, understood very well that all white men were not created equal, especially when it came to property and what they referred to as “virtue,” a much admired “elite attribute” which can be traced back to Aristotle himself, in his classic work, Nicomachean Ethics, who defined the only life worth living as “a life of leisure” – that is a life of study and freedom for the few which rested on the labor of slaves and proprietorship.[71] As thus revealed, the material forces and benefits which dictated southern elites to see Negroes, mulattoes, and Indians as one, also “dictated that they see large and small planters as one.” Consequently, racism became an essential, if unacknowledged, ingredient woven within that “republican ideology” that enabled Virginians to not only design, but to “lead the nation,” for generations to come. An important question thus addressed: Was the ideological vision of “a nation of equals” flawed from the very beginning by the evident contempt, exhibited, toward both poor whites and enslaved blacks? And beyond that, to be further explored within the final chapter of this research project: Are there still elements of colonial Virginia, ideologically, ethnically, and socially, woven within America today? More than a century after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox (on April 9th, 1865) – those questions per race and class still linger….[72]

As Edward E. Baptist, Professor of History at Cornell University, makes clear in his epic work, The Half Has Never Been Told, Slavery and The Making of American Capitalism, attitudes toward race and race superiority in America long remained. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, America’s first generation of professional historians, he argues, “were justifying the exclusion of Jim Crow and disfranchisement” by telling a story about the nation’s past of slavery and civil war that seemed to confirm, for many white Americans, that “white supremacy was just and necessary.” In fact, Baptist proclaims that racism had not only become culturally accepted, but historically and socially grounded within a form of “race science” to be further explored in the final chapter of this study. He states that by the latter part of the nineteenth century, “for many white Americans, science had proven that people of African descent [if not the poor in general] were intellectually inferior and congenitally prone to criminality.” As a result, he argues, that that cohort of racist whites in [Jim Crow] America, “looked wistfully to [the] past when African Americans had been governed with whips and chains.” Confirming the fact that class, race, and racism have long been integral parts of America’s long and difficult history.[73]

American capitalism, land, cotton, slaves, and profit: by the early nineteenth century, the U.S. Banking system was fundamental when it came to entrepreneurial revenue development in the form of land acquisition, cotton production, and slave labor. Bank lending became the key ingredient that propelled slave owners to greater heights of wealth accumulation, “Enslavers benefited from bank-induced stability and steady credit expansion.” The more slave purchases that U.S. Banks would finance, the more cotton enslavers could produce, “and cotton [at the time] was the world’s most widely traded product.” As mentioned, in this newly devised system of capital, lending, and borrowing, cotton was an essential resource in an unending global market. So, the more cotton slaves produced, the more cotton enslavers would sell, and thus the more profit they would make. In fact, “owning more slaves enabled planters to repay debts, take profits, and gain property that could be [used as] collateral for even more borrowing.”[74] Early U.S. Capitalism not just undergirded, but bolstered and expanded the harsh and inhumane system of slavery as such, “Lending to the South’s cotton economy was an investment not just in the world’s most widely traded commodity, but also in a set of producers who had shown a consistent ability to increase their productivity and revenue.”[75] Said differently, American slave owners, throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, had the “cash flow to pay back their debts.” And, the debts of slave owners were secure, given the fact that they had “a lot of valuable collateral.” In fact, as argued by a number of economic historians, enslavers, by mid-century had in their possession the largest pool of collateral in the United States at the time, 4 million slaves worth over $3 billion, as “the aggregate value of all slave property.”[76] These values embedded themselves in a global system of investment through slave commodification which benefitted mostly the upper crust of society in both the U.S. and the U.K., “this meant that investors around the world would share in revenues made by ‘hands in the field.’” Even though at the time, and to its credit, “Britain was liberating the slaves of its empire,” British banks could still sell, to a wealthy investor, a completely commodified human being in the form of a slave – not as a specific individual, but as a holding or part of a collective investment venture “made from the income of thousands of slaves.”[77]

Furthermore, as mentioned, the fact that popularly elected governments repeatedly sustained such bond schemes, on both sides of the Atlantic, was therefore not only insidious by its very nature, but at the same time remarkable. Popular abolitionist movements were springing up from one side to the other, and demanding abolition across the board. Beyond that, in the United States, there were many elements of class recognition in the form of an “intensely democratic frontier electorate” of both slaves and poor whites that saw banks as “machines designed to channel financial benefits and economic governing power to the unelected elite.”[78] By mid-century, the rift and divisions between the North and the South became catastrophic in the form of a bloody Civil War. It took a poor boy from a dirt-floor cabin in Kentucky named Abraham Lincoln, who rose to the prominence of lawyer and statesman becoming the 16th President of the United States, to write and implement the Emancipation Proclamation brought forth on January 1st, 1863. As President, Abraham Lincoln issued that historic decree, which served not only as a direct challenge to “property ownership,” in the form of human bondage, but a direct assault on the lucrative southern slaveocracy as the nation approached its third year of bloody civil war. The proclamation declared “that all persons held as slaves within the rebellious states are, and henceforward shall be free.”[79] Although Lincoln’s, contribution has been much contested to this day, by historians both Black and white alike, the fact remains that, his efforts as already presented, were undoubtedly a more active and direct support for the freedom of African slaves than those of all the fifteen previous presidents before him combined – The Emancipation Proclamation would prove to be the most important executive order ever issued by an American president, offering the possibility of freedom to an enslaved people held in a giant dungeon that was the confederacy.[80] Even though there are those historians that argue that the Proclamation was incomplete due to the fact that it “excluded the enslaved not only in Union-held territories such as western Virginia, but also southern Louisiana” where there were pro-Union factions that were trying not to be antagonistic toward local whites who were hell-bent on maintaining the status quo.[81]

But facts speak for themselves, Abraham Lincoln had been working diligently to persuade the political class in the border states that were loyal to the Union to agree to a “gradual or compensated” emancipation plan – pushing back against the benefactors of the race and class divide. Even though some within the border states refused to give in and held out for permanent slavery, by April 1862, because of Lincoln’s tenacious efforts, Congress passed legislation “freeing – in return for payments to enslavers totaling $1 million – all 3,000 people enslaved in the District of Columbia, Maryland, Delaware and Kentucky.” After the Union army’s victory at the battle of Antietam, Lincoln felt “he could move more decisively” against the institution of slavery and hence released that historic executive order which he had written months earlier as outlined above.[82] Undoubtedly, again, the Emancipation Proclamation offered for the first time in American history the unquestioned possibility of freedom to a long-held and enslaved people that were seized in a giant open-air prison which was the American South. The Emancipation did unbar the door. Next, enslaved Africans, due to their own agency, forced it wide open.[83]

As an exemplar of that heartfelt commitment, stood Frederick Douglass (1818 – 1895), former slave in his home state of Maryland, who rose to become a historic social reformer, abolitionist, writer, orator, and statesman. Lincoln was the first U.S. President in a long line, to invite an eminent African American intellectual, such as, Frederick Douglass to the White House to discuss the wonton discrimination within the military ranks cast upon African American men. That well-known meeting between Lincoln and Douglass took place in August 1863, two years after the start of the war on April 12, 1861. Douglass tenaciously argued for the enlistment of Black soldiers in the Union Army based largely on his legendary speech delivered at the National Hall in Philadelphia (on July 6, 1863), a month prior, entitled “the Promotion of Colored Enlistments,” outlined in the well-known publication The Liberator, that same month. Where Douglass stated:

Let the black man get upon his person the brass letters US … a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States.[84]

Douglass presented the same argument to Lincoln, that “Black men in Blue” would not only swell the ranks of the Union Army but would elevate those former slaves to the status of free men of honor – shifting the course of American history.[85] Lincoln took decisive action, per Douglass’ request, enlisting nearly 200,000 battle-ready African Americans, understanding that without those Black soldiers, there would be no Union. As a result, Douglass wholeheartedly endorsed the President for his coming reelection on November 8, 1864. “The enlistment of blacks into the Union Army was part of Lincoln’s evolving policy on slavery and race.”[86] Ultimately, he paid the price. On April 14, 1865, the 16th President of the United States was brutally slain by an assassin’s bullet for his valiant efforts against the racist slavocracy known as the Confederacy – Lincoln died at 7:22 a.m. on April 15, 1865.[87] The Civil War ultimately nullified the barbarity of slavery, which was later codified in the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, true, yet prejudicial elements of both race and class remained a fixture in American society for decades to come….

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, the coalescing or coming together from a class perspective of the lower ranks in the American South, later revealed itself in the formulation of the “Colored Farmers’ Alliance,” which stood as a direct threat to the established southern regime leading to a brutal and repressive racialized crackdown in the form of the Ku Klux Klan and the implementation of an oppressive social order known as Jim Crow – to be further explored within this study.

3

The Atomization of the Powerless

and the Sins of Democracy

Finally, as alluded to, the appellation and/or utilization of the term “race” was seldom employed by Europeans prior to the fifteen-hundreds. If the word was used at all, it was used to identify factions of people with a group connection or kinship. Over the proceeding centuries, the evolution of the term “race,” that came to comprise skin color, levels of intelligence and/or phenotypes, was in large part a European construct – which served to undergird a strategy of division amongst the masses that helped to maintain a stratified class structure with “elite white land-owning men” placed firmly at the top of the social-ladder in that newly birthed land of “freedom” called America.

As succinctly stated by David Roediger, esteemed Professor of American history at the University of Kansas, who has taught and written numerous books focused on race and class in the United States, “The world got along without race for the overwhelming majority of its history. The U.S. has never been without it.”[88] Nothing could be further from the truth. As outlined in previous chapters, American society uniquely and legalistically formulated the notion of “race” early on to not only justify, but support its new economic system of capitalism, which rested in large part, if not exclusively, upon the exploitation of forced labor – that is, the brutal enslavement and demoralization of African peoples. To understand how the development of race and its bastardized twin “racism” were fundamentally and structurally bound to early American culture and society we must first survey the extant history of how the notions of race, ethnocentrism, white supremacy, and anti-blackness came to exist.

The ideas that undergirded the notions of “race, a class-stratified stratified slave society, as we recognize them today, were birthed and developed together within the earliest formation of the United States; and were intertwined and enmeshed in the phraseologies of “slave” and “white.” The terms “slave,” “white,” and “race” began to be utilized by elite Europeans in the sixteenth century and they imported these hypotheses of hierarchy with them to the colonized lands of North America. That said, originally, the terms did not hold the same weight they have today. However, due to the economic needs and development of that early American society, the terms mentioned would transform to encompass new racialized ideas and meanings which served the upper class best. The European Enlightenment, defined as, “an intellectual movement of the 17th and 18th centuries in which ideas concerning god, reason, nature, and humanity were synthesized into a worldview that gained wide assent in the West and that instigated revolutionary developments in art, philosophy, and politics,”[89] would come to underpin and contribute to racialized perceptions which argued that, “white people were inherently smarter, more capable, and more human than nonwhite people – became accepted worldwide.” In fact, from an early American perspective, “This [mode] of categorization of people became the justification for European colonization and subsequent enslavement of people from Africa.”[90] To be further surveyed.

As Paul Kivel, noted American author, social-justice educator and activist, brings to the fore, the terms “white” or “whiteness,” historically, from a British/Anglo-American perspective, served to underpin class distinctions and justify exploitation through human bondage by providing profit-accumulation to a distinct ownership class, “Whiteness is [historically] a constantly shifting boundary separating those who are entitled to have privileges from those whose exploitation and vulnerability to violence is justified by their not being white.”[91] Where and how did it begin? The conception of “whiteness” did not exist until roughly 1613 or so, when Anglo-Saxon forces, later known as the English, first “encountered and contrasted themselves” with the Indigenous populations of the East Indies – through their cruel and rapacious colonial pursuits – later justifying, and bolstering, a collective cultural sense of racial superiority. Up and until that point, roughly the 1550s to the 1600s, within Anglo-Saxon society, “whiteness” was used to set forth clear class signifiers.

In fact, the word “white” was utilized exclusively to “describe elite English women,” because the whiteness of their skin indicated that they were individuals of “high social standing” who did not labor “out of doors.” That said, conversely, throughout that same period, the appellation of “white” did not apply to elite English men, due to the stigmatizing notion that a man who would not leave his home to work was “unproductive, sick and/or lazy.” As the concept of who was white and who was not began to grow, “whiteness” gained in popularity within the Anglo-American sphere, for example, “the number of people that considered themselves white would grow” as a collective pushback against people of color due to immigration and eventual emancipation.[92] These social constructs centered around race accomplished their nefarious goals – thus, unifying early colonists of European descent under the rubric of “white,” and hence, marginalizing, stigmatizing and dispossessing native populations – all the while permanently enslaving most African-descended people for generations. As acclaimed African American Professor, Ruth Wilson Gilmore (director of the Center for Place, Culture, and Politics at CUNY) contends concerning America’s base history, “Capitalism requires inequality and racism enshrines it….”[93] A revelatory statement by John Jay (1745-1829, the first Chief Justice of the United States and signer of the U.S. Constitution) helps make evident, from a class perspective, the entrenched values of those early American elites toward their newly proclaimed democracy, “The people who own the country ought to govern it!”[94] The preceding two quotes help to summarize and clarify the top-down legal and societal mechanisms embedded within that early American social stratum which linger to this day.

The social status and hence the nomenclature of “slave” have been with mankind for millennia. Historically, a slave was one who was classified as quasi-sub-human, derived from a lower lineage; and forced to toil for the benefit of another of higher standing. We can find the phraseology of slave throughout the ancient world and within early writings from Egypt, the Hebrew Bible, Greece, and Rome, as well as later periods. In fact, Aristotle (384 to 322 BC, famed polymath, and philosopher) succinctly clarified, from his privileged vantage-point, the social standing and value of personages classified as slaves – which would endure for epochs to come. From the legendary logician’s point of view, a slave was defined as, “one who is a human being belonging by nature not to himself [or herself] but to another is by nature a slave.” Aristotle further described a slave as, “a human being belongs to another if, in spite of being human, he [or she] is a possession; and as a possession, is [simply a tool for labor] having a separate existence.”[95] Clarifying the fact that in the known world prior to Columbus’ famed voyage, in the late 15th century, opening the floodgates of European colonial theft, pillage, and domination, historical notions of Western hierarchy and supremacy were commonplace. As European Enlightenment ideals such as, “the natural rights of man,” aforementioned, became ubiquitous amongst early American colonial elites throughout the 18th century, “equality” became the new modus operandi which galvanized whites over and above all others. Hence, by classifying human beings by “race,” a new method of hierarchy was established based on what many at the time considered “science” to be further explored. As the principles of the Enlightenment penetrated the colonies of North America forming the basis for their early “democracy,” those same values paradoxically undergirded the most vicious kind of subjugation – chattel slavery.[96]

A significant codified shift took place in colonial America within one of its most prosperous slave domains known as Virginia. Under the tutelage and guidance of the then Governor Sir William Berkeley (1605-1677), wealthy planter and slave owner, the House of Burgesses (the first self-proclaimed “representative government” in that early British colony) included a coterie of councilors hand-chosen by the governor to enact a law of hereditary slavery – which would economically serve their elite planter class interests. The English common law, known as, Partus Sequitur Patrem, traditionally held that, “the offspring would follow the condition … of the father.”[97] But after a historic legal challenge brought by Elizabeth Key, an enslaved, bi-racial woman who sued for her freedom and won, in 1656, on the basis that her father was white – elite white Virginians understood that a shift in the law was not only necessary, but essential, if they were to maintain and/or increase their wealth through human bondage in the form of “property ownership.” Consequently, the new 1662 law, Partus Sequitur Ventrem, diverged from English common law, in that it proclaimed that the status of the mother, free or slave, determined the status of her offspring in perpetuity.[98] Thus, African women were subjugated to the ranking of “breeders,” that would serve to produce more offspring categorized as slaves, whether bi-racial or not, and hence more profit for the ruling class. Enlightenment values ensconced in a rudimentary “race science,” by famed early Americans, would also help to solidify a systematized racialized hierarchy for decades to come.[99]

Figure 7: Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), Diplomat, Son of the Enlightenment, Planter, Lawyer, Philosopher, Primary Author of the Declaration of Independence and Third President of the United States.

Thomas Jefferson is famed to be one of the most quintessential characters in the formulation of America’s early Republic, along with James Madison and others, severing foreign rule and developing a new independent nation, substantiated on the Enlightenment principles of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,”[100] based largely on John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government, which argued that true “freedom” is defined by one’s singular control over their holdings and/or estates, i.e., property.[101] But the most basest question which still lingers, within America’s long and twisted historical tragedy of early conquest and domination, which must be probed, is, “freedom for whom and for what?” Jefferson, that complex and enigmatic son of Enlightenment thought, both in science and sociological principles, clearly demarcated and endorsed a racialized societal structure that undergirded a system of hierarchy in which white colonists and their European legacy were considered far superior to all others – simplified notions woven within an early race science which would endure through time and memorial. Throughout his lifetime, race was defined by phenotype (or the look of human beings), physical characteristics which “appended physical traits [or idiosyncrasies] defined as ‘slave-like’ [were attributed] to those enslaved.”[102] As Karen and Barbara Fields, two noted African American scholars, point out, Jefferson became convinced that a forced separation of people delineated by skin color was the only solution; that “the very people white Americans had lived with for over 160 years as slaves would be, after emancipation, too different for white people to live with any longer.”[103] In fact, he suggested that if slaves were to be freed they should be promptly deported, their lost labor to be best supplied “through the importation of white laborers.”[104]

Jefferson unabashedly qualified his racialized views when writing, “I advance it therefore as a suspicion only that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.”[105] John Locke and Thomas Jefferson stood in agreement, philosophically, when it came to the superiority versus inferiority of selected “races,” underpinning a racialized stratification within early colonial thought that helped to culturalize a race-based hierarchy in that newly formed “land of freedom,” known as the United States. These arguments of hierarchy which spread throughout the European mindset within that early colonial era, aided and abetted, “the dispossession of Native Americans” and “the enslavements of Africans” during that golden era of revolution.[106] In his historic manuscript known as, Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson outlined in detail his Enlightenment-inspired racialized interpretations of European superiority, demarcating what he believed to be a “scientific view” of the varying gradations of human beings based on race:

Comparing them [both blacks and whites] by their faculties of memory, reason, and imagination, it appears to me, that in memory they are equal to the whites; in reason much inferior … and that in imagination they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous. But never yet could I find that a black has uttered a thought above the level of plain narration; never see even an elementary trait, of painting or sculpture.[107]

Ironically, given the complexity of the man, in response to a critic who opposed his views as presented above, Jefferson confessed that even if blacks were inferior to whites, “it would not justify their enslavement.”[108] Hence, to his credit, he admitted and/or recognized the strangeness and/or irony of his own position when it came to Enlightenment constructs of race and their structural consequences.[109] Again, from early on, racialized notions of superiority versus inferiority served the American planter class best, by cleverly embedding perceptions of hierarchy or white preeminence, they were able to suppress that which they feared most – which was the unification or coming together of a mass of lower classes comprising both enslaved Africans and poor whites. The historic incident which, served as an exemplar, sending shockwaves through that propertied class of early colonial America was notably Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676.

Nathaniel Bacon (1647-1676) elite Virginian, born and educated in England, member of the governor’s Council and close friend of Sir William Berkeley then colonial Governor – led a bottom-up rebellion which sent tremors through the upper classes of that newly birthed slave society, known as, Virginia – still considered one of the most foundational events of early American history. The colonial elite were threatened on all sides, as made evident by Governor Berkeley’s revelation, “The Poore Endebted Discontented and Armed” would, he feared, use this opportunity to “plunder the Country” and seize the property of the elite planters.[110] Bacon, “who was no leveler,” was cleverly able to formulate a coalition (or unification), on behalf of his class interests, which included poor white indentured servants, free and enslaved Africans, to push back against any and all encroachments by native inhabitants which included the Appomattox and Susquehannock indigenous tribes of the region, in order to cease their lands and enrich himself and his class even further, insisting that, “the country must defend itself ‘against all Indians in general for that they were all Enemies.’”[111] Some one hundred years later, in his acclaimed paradox of liberty known as the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, obviously influenced by Bacon’s racialized frame of thought, referred to the indigenous Native American peoples as nothing more than, “merciless Indian savages.”[112] Hence, the native populations of that early America were collectively used as “scapegoats,” to enlarge the land holdings and wealth of the propertied class. From early on, the United States’ nascent form of Capitalism became dependent upon exploitative low-cost labor, “especially that of those considered nonwhite,” but also that of “the poor in general, including women and children – black and white alike.”[113] Ironically, by the 1850s, antislavery sentiment grew even more intense amongst the masses, largely spurred on by white Southerner’s aggressive attempts to maintain the societal structure as such through political dominance and the spread of that “peculiar institution,” known as slavery to newly pilfered lands.[114] In turn, the very idea of the possibility of any and all “lower class unity,” or a coming together of poor white indentured servants and African slaves as a militant force rising up against an entrenched planter class, brought forth a racialized culturalization grounded upon racial difference, racial hierarchy, and racial enmity, “a pattern that those statesmen and politicians of a later age would have found [politically useful and] familiar.”[115] In fact, right through to the end of the 19th century, post-Civil War and Reconstruction era (1865-1877), any form of lower-class unity in America stood as a direct threat to the established order of things throughout the nation as a whole; and especially throughout the South – most notably in the form of the Colored Farmers’ Alliance and the South’s reactionary implementation of a brutal social-order of domination and control known as Jim Crow.

Figure 8: Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865), American Lawyer, Statesman and Politician. Sixteenth President of the United States and Author of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Although historically contentious, Abraham Lincoln’s primary goal within his Reconstruction scheme was to reunite a fractured nation after a bloody and costly Civil War. Through which, Lincoln’s objective was to reestablish the union and transfigure that implacable Southern society. His plan was also stridently committed to enforcing progressive legislation driven by the abolition of slavery. In fact, Lincoln directed Senator Edwin Morgan, chair of the National Union Executive Committee, to put in place a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. And Morgan did just that, in his famed speech before the National Convention on May 30, 1864, demanding the “utter and complete extirpation of slavery” via such an amendment.[116] Beyond the Emancipation Proclamation, Abraham Lincoln was the first President in American history to call forth an amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolishing the long-held institution of chattel slavery. For the first time, President Lincoln demanded the eventual passage of the Thirteenth Amendment Section 1 (ratified on December 6, 1865), which mandated that, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”[117] Defining it as “a fitting, and necessary conclusion” to the war effort that would make permanent the joining of the causes of “Liberty and Union.”[118] Lincoln’s sweeping Reconstruction agenda was a fight for freedom, requiring the South to adhere to a new constitution that would implicitly include black suffrage through the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment Section 1, ratified after his death on July 9, 1868, which for the first time in American history, declared:

All persons [meaning black and white alike] born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.[119]

Abraham Lincoln, the Great Emancipator, saw his Reconstruction struggles above all as, “an adjunct of the war effort – a way of undermining the Confederacy, rallying southern white Unionists, and securing emancipation,”[120] for which he paid the ultimate price. From early on, internecine rivalry, or infighting, within the Republican Party from those labeled as “the Radicals,” led to a push-back against certain elements of Lincoln’s strategy mentioned above – arguing that Reconstruction should be postponed until after the war, “as outlined in the Wade-Davis Bill of 1864, which clearly envisioned, as a requirement, that a majority of southern whites take an oath of loyalty,” to the United States; and that the federal government should by necessity, “attempt to ensure basic justice to emancipated slaves.” A point at which, “equality before the law,” not “black suffrage,” as Lincoln had suggested, was an essential factor for many of the Republicans in Congress at the time.[121] As a result of Lincoln’s efforts in taking away the productive forces of labor within the South, and in turn, the diminishment of property, wealth, and political power of the elite southern planter class, a nefarious conspiracy to murder the President was hatched and executed by southern loyalist and assassin John Wilks Booth, on April 14, 1865, while the President sat accompanied by his wife, Mary, watching a play titled, Our American Cousin, at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. – oddly, the assassin was able to gain access to the theater, enter the Presidential Booth, and shoot and kill the President of the United States. Lincoln’s body was carried to the nearby Petersen House, where he passed away at 7:22 a.m., the following morning. At his bedside, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton famously remarked, “Now he belongs to the ages.”[122] Reflecting upon not only the uniqueness of the man, but his tremendous contributions to those American ideals of “Liberty and Freedom.” Emphasizing the fact that the Emancipation of Africans from forced labor; and the abolishment of chattel slavery, through a stroke of his pen, uniquely placed Abraham Lincoln in the pantheon of historical renown.

That said, throughout the end of the 19th Century, the road ahead per class relations for African Americans and poor whites alike, especially in the South, would be a hard and arduous one of top-down control and division. Reactionary as they were, as argued, Southern elites would forcefully implement doctrines of superiority, separation, and control that would crush and/or punish any form of lower-class unity which threatened their power and influence over the majority. This reaction would become most evident in the racialized militant form of the Ku Klux Klan; and later the structural control and dominance of an imposed social order known as Jim Crow, which would orchestrate the groundwork for a deepening racial divide.