A potential tie-up between Rio Tinto Group and Glencore Plc would rank among the largest transactions ever attempted in the mining sector. The combined company would be valued at roughly $260 billion and would control a broad mix of iron ore, copper, and other industrial metals at a point when supply growth across several markets is slowing.

The structure of the two companies explains why the idea continues to resurface. Rio’s iron ore business generates steady and predictable cash flow. Glencore, by contrast, has spent the past decade building one of the industry’s largest copper portfolios while maintaining a global trading operation that handles large volumes of physical metals. Together, those businesses would cover both production and distribution at scale, a combination few miners can match.

According to multiple reports, Rio Tinto and Glencore are holding preliminary discussions about a possible merger. The talks remain early and non-binding, with no formal proposal or timetable disclosed. Interest in the scenario has increased after BHP Group ruled out a competing bid.

BHP’s decision narrows the competitive field. With a market capitalization of around $168 billion, BHP was the only miner with the balance sheet and operational reach to pursue a rival transaction. With that option removed, attention shifts to whether a single Rio-Glencore deal can move forward without the uncertainty of a bidding contest reshaping valuations or delaying execution.

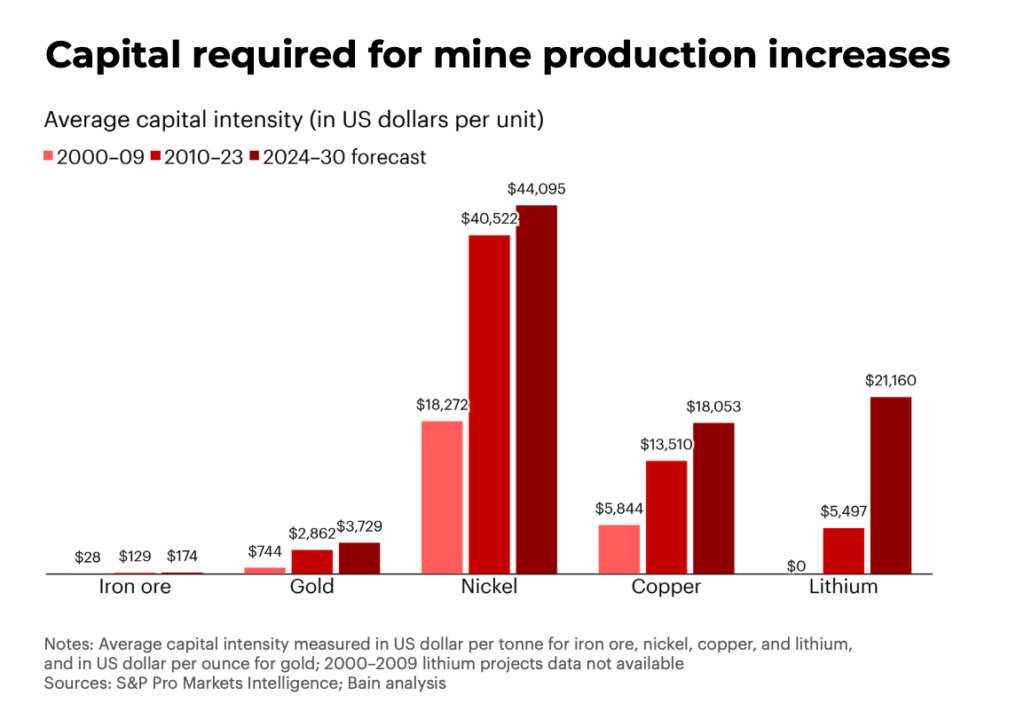

Copper is key here. Demand continues to rise from power grids, electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, and data centers. Supply growth remains limited. Years of underinvestment, declining ore grades, permitting delays, and higher development costs have slowed the pipeline of new projects. Glencore’s copper assets and expansion plans would materially increase Rio’s exposure to a market that is already tight.

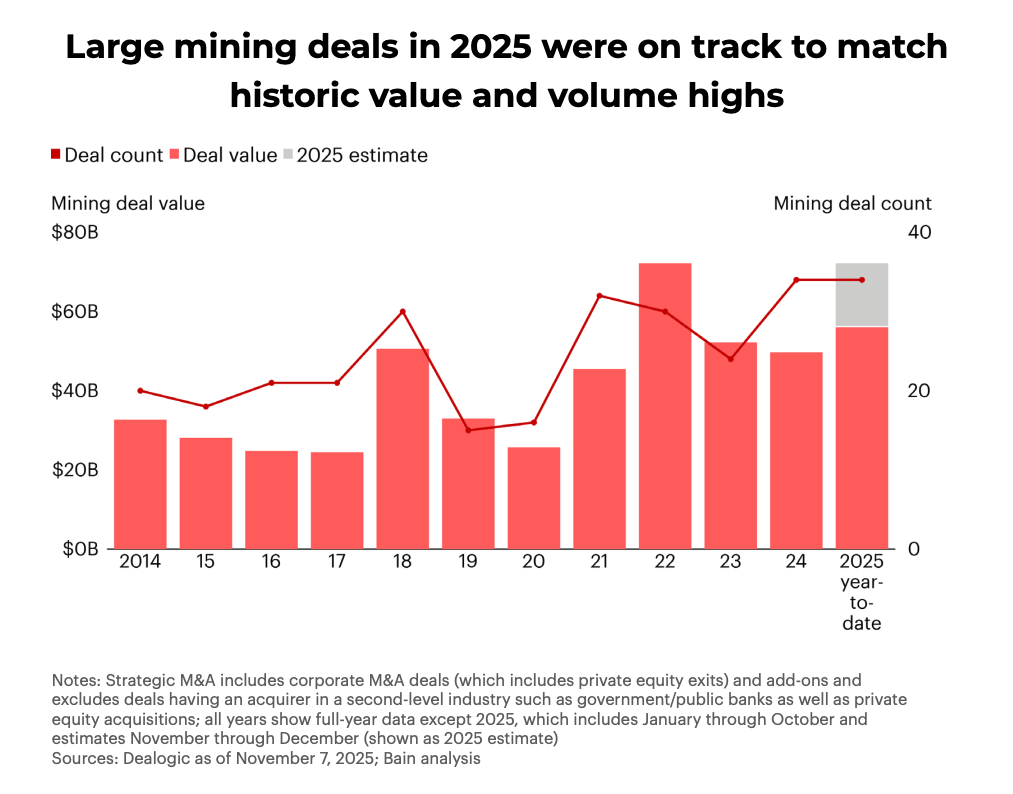

The talks also come as the mining sector accelerates its push toward consolidation. Producers are seeking scale to manage rising costs, longer project timelines, and tighter capital conditions. A proposed tie-up between Anglo American and Teck Resources is one example, with the companies exploring a merger of equals that would create a major copper-focused producer based in Canada. Similar pressures are driving interest in larger, more diversified mining groups across the industry.

For Rio, a deal with Glencore would also bring a commercial advantage. Glencore operates one of the most powerful commodity marketing and trading businesses in the mining sector, giving it deep exposure to physical flows, regional pricing differences, and supply disruptions. Integrating that operation would add a capability Rio currently lacks, strengthening its position across copper and other metals markets.

Beyond operating scale, the structure of Glencore’s portfolio opens up options to unlock shareholder value. The company’s carbon-heavy businesses, particularly coal, generate substantial cash but continue to weigh on valuation. Separating those assets following a merger could leave a standalone metals business centered on copper, zinc, aluminium, and lithium. That mix would align more closely with producers that trade at higher valuation multiples than diversified miners with large coal exposure.

Analysts cited by the Financial Times have argued that a post-merger break-up could materially lift shareholder value by allowing the metals business to be valued on its own merits, rather than alongside coal. Rio and BHP both trade at lower multiples than copper-focused peers, while coal-heavy producers trade at an even deeper discount. Keeping those businesses separate would highlight the difference in how they are valued.

Prices seem to track with this. Copper has climbed more than 25% over the past three months and reached record levels above $13,000 a tonne on the London Metal Exchange. Inventories remain low by historical standards, while producers face higher costs across labor, energy, and equipment. New supply is expected, but much of it remains several years away from first production.

Glencore’s appeal extends beyond its mines. The company operates one of the largest metals trading businesses in the world, giving it direct exposure to physical flows, pricing differentials, and regional supply disruptions. That trading arm has long differentiated Glencore from traditional miners. Folded into Rio, it would add a commercial layer that most large producers lack, potentially reshaping how the combined group markets copper and other metals.

The talks also come as consolidation accelerates across the sector. Large miners are increasingly using scale to manage cost inflation and longer project timelines. Smaller producers face tighter financing conditions and limited flexibility when projects run over budget or encounter delays. A combined Rio–Glencore would sit firmly at the top end of the industry, with the ability to keep large projects moving through downturns that would strain less diversified peers.

Coal is the awkward part of any deal. Glencore is one of the world’s largest coal producers, and those operations generate substantial cash that has supported the company during weaker metals cycles. At the same time, coal continues to weigh on valuation as capital flows favor copper and other electrification-linked metals. Separating those assets would leave a cleaner metals business, but it would also remove a significant source of earnings.

Glencore has been here before. The company has previously reviewed options to separate its coal business, only to see shareholders decide to keep the assets because of the cash they generate. Any deal with Rio would put that question back on the table, this time tied directly to how a combined company would be valued rather than to longer-term climate positioning.

Regulators would also be involved early. Authorities in Australia and Europe would examine copper concentration, particularly in regions where both companies already have significant operations. Glencore’s trading business would draw additional scrutiny because of its role in physical markets and price setting. Any transaction would need approvals across several jurisdictions.

The two companies also run very different models. Glencore’s operations are built around trading and risk management, while Rio focuses on long-life mining assets and production discipline. Combining those approaches would require changes in oversight, internal controls, and decision-making.

Even if the talks go no further, they reflect where the industry is headed. Copper assets with long reserve lives are becoming harder to secure. Cash flow is increasingly important as project costs rise and timelines stretch. Those pressures continue to favor larger miners with the balance sheets to fund new supply and absorb delays.

By Alex Kimani for Oilprice.com

Stock image.

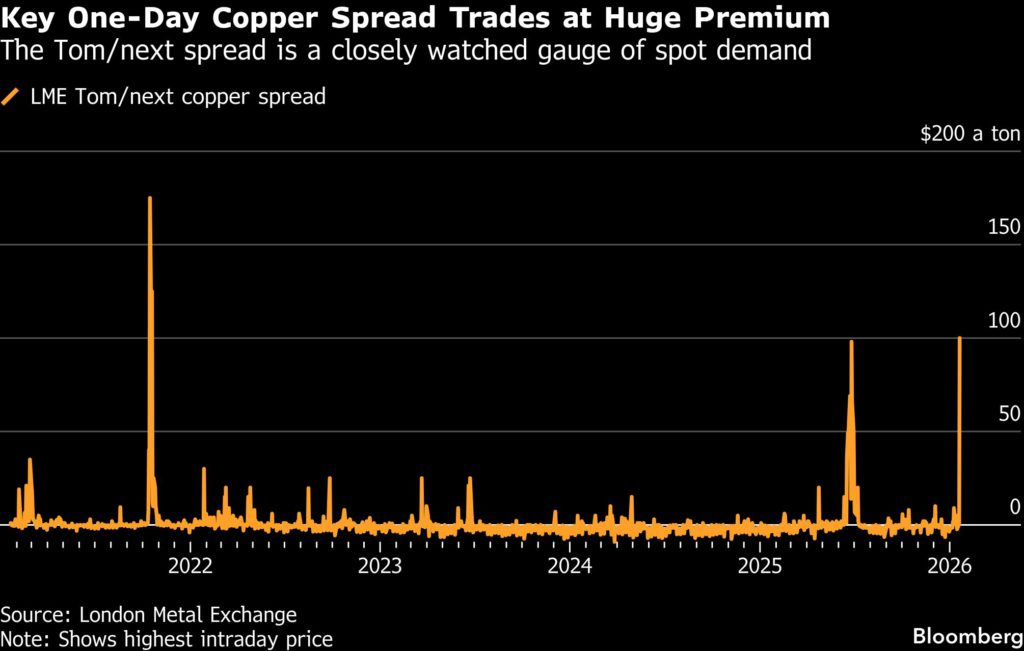

Spot copper prices surged to trade at a huge premium over later-dated futures on the London Metal Exchange, with a closely watched one-day spread reaching levels not seen since an historic supply squeeze in 2021.

Copper contracts expiring Wednesday briefly traded at a $100 premium to those expiring a day later, in a structure known as backwardation that typically signals rising spot demand. The so-called Tom/next spread was at a narrow discount on Monday, and the spike was among the largest ever seen in pricing records starting in 1998.

The surge creates a fresh bout of turmoil in the LME copper market, after a breakneck rally that lifted prices to record highs above $13,400 a ton earlier this month. Traders have been piling into the market as mines have faltered and a surge in shipments to the US has drained copper supplies elsewhere, while many investors are betting on a jump in demand to power the burgeoning artificial-intelligence industry.

The Tom/next spread is closely watched as a gauge of demand for metal in the LME’s warehousing networking, which underpins trading in its benchmark futures contracts. The advance came ahead of the expiry of the LME’s main January contracts on Wednesday, with the Tom/next spread providing a final opportunity to trade those positions.

Data from the LME showed that there were three separate entities with long positions equal to at least 30% cumulatively of the outstanding January contracts as of Friday, and if held to expiry the positions would entitle them to more than 130,000 tons of copper — more than the amount that’s readily available in the LME’s warehousing network.

Holders of short positions, meanwhile, would need to deliver copper to settle any contracts held until expiry, and the spike in the Tom/next spread exposes them to hefty losses if they look to roll them forward instead. The move to $100 a ton took the spread to the highest level since a major supply squeeze in 2021, which prompted the LME to roll out emergency rule changes to maintain an orderly market.

Structural constraints

The Tom/next spread often flares into backwardation in the run-up to the expiry of monthly contracts, but such extremes are a rarity — partly because the LME has rules in place that force large individual holders of long positions to lend them back to the market at a capped rate.

The spread had earlier been trading at a premium of $65 a ton, which equates to 0.5% of the prior day’s official cash price. That’s the maximum level participants can lend at if they hold positions in inventories and spot contracts that are equal to between 50% and 80% of readily available stocks. The spread later fell in the final minutes of trading, and closed at $20 a ton at 12:30 p.m. London time.

While the Tom/next spread is highly volatile, copper’s broader price curve is also signaling more structural supply constraints in the broader copper industry, with backwardation seen in most monthly spreads through to the end of 2028. Many analysts and traders expect the market to be in a deep deficit by then, in a trend that could drain global inventories and push prices sharply higher.

Global inventories are at sufficient levels for now, but much of the stock is held in warehouses in the US, after traders shipped record volumes there in anticipation of tariffs. The once-in-a-lifetime trading opportunity was fueled by a surge in copper prices on New York’s Comex exchange, but the recent spike in spot prices on the LME has left US futures trading at a discount.

This week, there have been small deliveries of copper into previously empty LME warehouses in New Orleans, and the surge in the Tom/next spread could incentivize further deliveries into US depots. Data from the LME shows that there were about 20,000 tons of privately held copper that could be readily delivered into New Orleans and Baltimore as of Thursday, while more than 50,000 tons were also held off-exchange across Asia and Europe.

LME copper inventories rose by 8,875 tons to 156,300 tons on Tuesday, driven by deliveries into warehouses in Asia and a small inflow in New Orleans. The turmoil in price spreads had little impact on the LME’s benchmark three-month contract, with prices falling 1.6% to settle at $12,753.50 a ton as US President Donald Trump’s push to take control of Greenland sparked a broad selloff in stock markets.

(By Mark Burton)

Copper production increased by 5% in Q4, driven by a surge from Mongolia’s Oyu Tolgoi underground expansion.(

Image courtesy of Turner & Townsend.)

Rio Tinto’s (ASX, NYSE, LON: RIO) copper production rose 5% in the fourth quarter, as a surge from Mongolia’s Oyu Tolgoi underground expansion more than offset weaker output at Chile’s Escondida, the world’s largest copper mine.

Copper accounted for about a quarter of Rio’s half-year profit, still dwarfed by iron ore but central to its long-term growth ambitions and the strategic backdrop to its ongoing takeover talks with Glencore (LON: GLEN), with a Feb. 5 deadline to either make a firm offer or walk away.

At Escondida, fourth-quarter production fell 10% from a year earlier due to lower grades and reduced concentrator output, but Oyu Tolgoi delivered a 57% year-on-year jump that underpinned the group’s overall copper gain.

“Rio Tinto finished the year with a strong performance in key commodities, including fourth-quarter Pilbara iron ore up more than 4% versus our estimate, a quarterly record, and a 4% beat in copper,” BMO Capital Markets mining analyst Alexander Pearce said in a note. “However, the near-term focus remains on the potential merger with Glencore.”

The UK’s strict takeover rules also meant that Glencore’s name was absent from Rio’s production report, yet the Swiss miner’s influence hangs over the results as negotiations continue on valuation, leadership, structure and asset composition.

Among the options under discussion is a carve-out of coal assets, potentially into a separately listed Australian vehicle, echoing BHP’s (ASX, LON: BHP) South32 demerger a decade ago.

Glencore’s coal operations across NSW, Queensland, central Africa and Latin America would make up about 8% of a combined group’s $45.6 billion in EBITDA, while its trading arm, accounting for roughly 9% of earnings, remains another sensitive element.

Analysts have also floated alternatives, including a pre-deal coal spin-off by Glencore or a narrower bid by Rio focused solely on copper assets.

Market timing

Mark Freeman, managing director of the near-century-old Australian Foundation Investment Company (AFIC), has questioned the timing of chasing Glencore’s copper pipeline with prices near record highs, warning that assets often appear most attractive at the top of a mining cycle.

RBC mining analyst Ben Davis struck a similar note, arguing that the strength of the copper market has shifted perceptions around a potential tie-up. “Clearly the mining cycle is alive and well,” he wrote in a note last week.

What was widely dismissed as speculative talk a year ago has, in his view, gathered momentum amid a strong rally and tightening resource supply, with recent share price moves signalling that investors now expect a firm offer.

The analyst added that Glencore’s copper portfolio, particularly its 44% stake in Chile’s Collahuasi mine alongside Anglo American (LON: AAL), represents the crown jewel Rio is seeking.

Iron backbone

Rio’s Pilbara iron ore operations hit a quarterly record, with shipments rising 7% to 91.3 million tonnes, while full-year exports landed at the lower end of guidance as the company recovered from weather disruptions.

The miner also began exporting from Guinea’s Simandou project and expects sales of 5 million to 10 million tonnes in 2026, compared with 323 million to 338 million tonnes forecast from the Pilbara this year. Elsewhere, aluminium output increased 2%, lithium production reached a record driven by Argentina, and titanium volumes fell 6% as Rio prepares to divest the business.

Since chief executive Simon Trott took the helm last year, Rio has moved to refocus operations, cut costs and rein in earlier ambitions in lithium. “Implementation of our stronger, sharper, simpler way of working continues, and is delivering results and creating value,” Trott said.