Conference attendees pause and observe the artwork inside the Conference Center prior to the Sunday morning session of General Conference on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, on Oct. 5, 2025. (Photo © 2025 by Intellectual Reserve Inc. All rights reserved.)

Conference attendees pause and observe the artwork inside the Conference Center prior to the Sunday morning session of General Conference on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, on Oct. 5, 2025. (Photo © 2025 by Intellectual Reserve Inc. All rights reserved.)Jana RiessDecember 10, 2025

RNS) — The research question I get asked more than any other nowadays concerns young adults who grew up in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Are more of them leaving the church now than in the past?

I hear it from parents, bishops and other LDS members who are deeply concerned as they observe more young adults abandoning Mormonism — including their own kids. But high-ranking church leaders have countered that this is just a “narrative” and that if anything, young people are “flocking” to the church in record numbers.

As evidence, they point to rising numbers of students enrolled in the church’s seminary and institute programs, an expanding global missionary force and a rebounding spate of new converts worldwide.

So, in a two-part series, I’ll share data trends about young Mormons in the United States. Today’s column focuses on how many people have left the church, while the next will look at the religiosity of young adult members who stay.

My research is limited to the U.S., so I can’t speak to the way the church is or is not growing abroad. But we can confirm from nationally representative data sets that the LDS church is indeed losing more members in the U.S. and that this disaffiliation is primarily driven by younger adults.

Alex Bass, as part of his Mormon Metrics Substack, has analyzed data from several national surveys while helping me and Benjamin Knoll with the quantitative research for our forthcoming book on the Mormon faith crisis. As always, when we’re looking at data about a small minority, we need to be mindful that the margin of error can be high. With this in mind, each of our graphs includes the error bars to show the range of possible findings.

But you can see that over the long term, there’s little question that more people are leaving the church now in the U.S. compared with in the past. The first graph from the General Social Survey, which asked about childhood religion as well as current religion, shows we’ve gone from retaining over three-quarters of childhood LDS members through the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, to keeping around 40% in the 2020s — a statistically significant drop.

General Social Survey data from 1973 to 2022, showing LDS retention rates of childhood members in the United States. (Analysis and graph by Alex Bass of Mormon Metrics)

Note that for those early years measured by the GSS, that 77% figure could be anywhere between 72% and 82%, since the subsample size, or n, is 247 respondents in the weighted data. And the error bars are spread even further apart for the 2020s crowd (with a sample size of only 105), meaning that the range could be as low as 29% or as high as 46%.

The GSS is a well-respected survey that has more than half a century of data to allow for long-term trend comparisons, but its LDS respondent numbers are still small. Also, it changed its methodology during the COVID-19 pandemic, so those 2020s numbers should be regarded with caution. This means that it’s good to look at other sources, such as Pew Research Center’s three Religious Landscape studies.

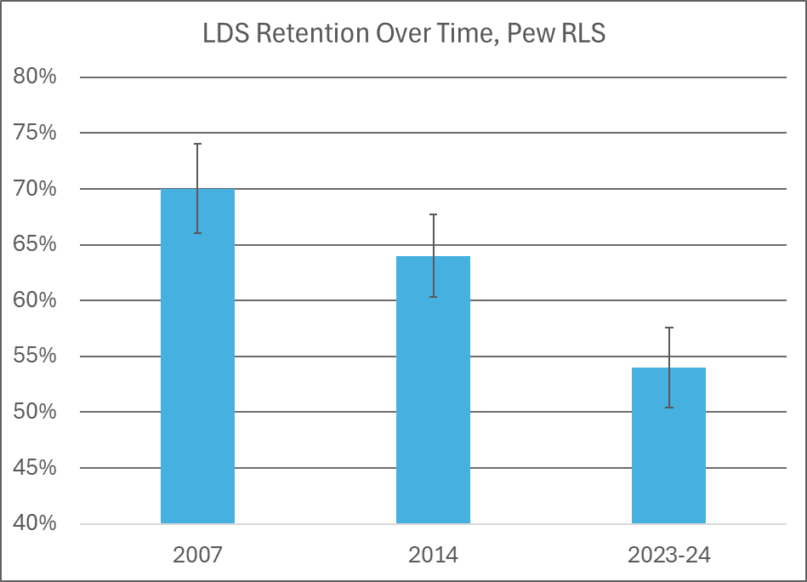

Pew Religious Landscape Study, LDS retention over time.

(Data analysis and graph by Benjamin Knoll)

In 2007, according to Pew, the LDS church retained 70% of childhood members in the U.S. (n = 581) In 2014, that was 64% (n = 661), and in 2023–24 it had declined still further to 54% (n = 525).

That 54% current retention rate looks better than the GSS’ 38%, so that’s potentially good news for LDS leaders. But once again, we’re witnessing a clear drop from the fairly recent past. Both major U.S. surveys that track childhood affiliation are saying that more people are leaving than used to.

What’s more, this is being driven by younger adults. In the general population, younger adults are noticeably more likely to have no religious affiliation than older adults — either because they’ve left religion or they grew up without one. It shouldn’t surprise us that it’s true in Mormonism as well.

But it often does surprise us, especially since other religions used to envy our retention of youth. As sociologist Christian Smith put it in his recent book “Why Religion Went Obsolete,” the LDS church was once “legendary for its impressive retention rates among young people.”

Smith was the lead researcher 20 years ago for the National Study of Youth and Religion. That longitudinal study’s findings were so positive for the LDS church that they were written up in the Church News and trumpeted by the church’s official newsroom in 2005, 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2013.

But the data isn’t so sunny anymore, according to Smith’s research. “While Mormon retention looked solid in the early 2000s, in the years since, as Millennial Mormons moved through emerging adulthood, they began exiting the LDS church in dramatic, unprecedented numbers,” he wrote.

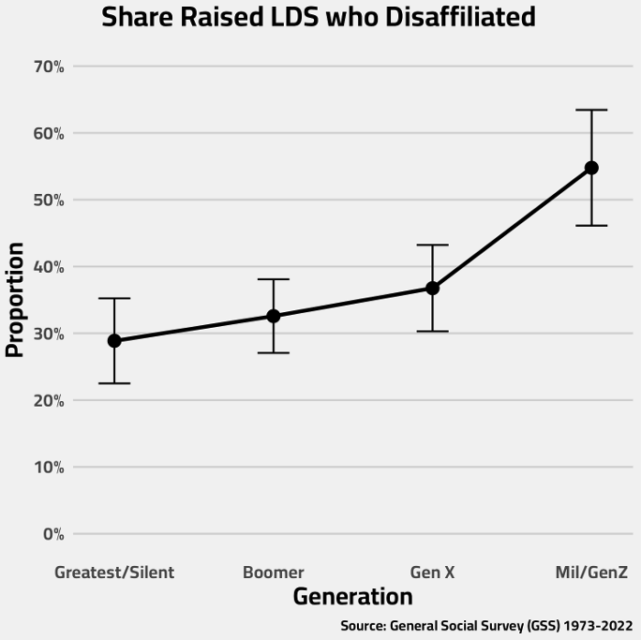

To demonstrate, here is Alex’s analysis of GSS data again, this time broken out by generation.

General Social Survey showing LDS retention by generation.

(Data analysis and graph by Alex Bass of Mormon Metrics)

According to the GSS, only 29% of Greatest and Silent generation members left the church in the U.S. That increased slightly to 33% for the baby boomers and 37% for Generation X. Then it shot up to 55% for millennials and Gen Z. And the difference between the oldest and youngest respondents is large enough that we can be confident it’s not just a statistical blip.

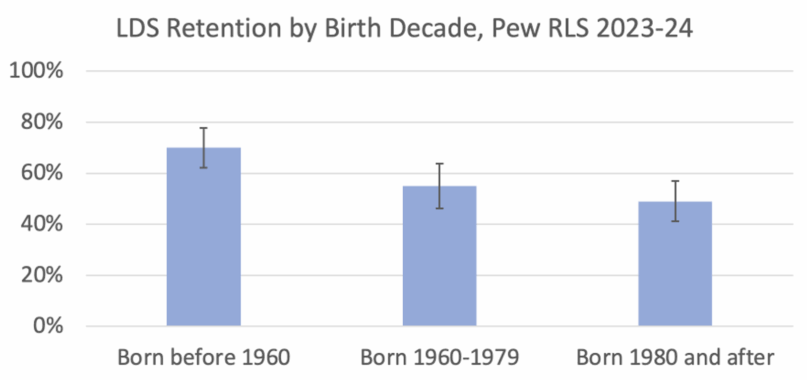

Ben’s analysis of Pew’s most recent data tells a similar story. The next graph shows a drop in retention between those born before 1960 (where 70% stayed LDS) and those born since 1980 (where only 49% stayed). The precise percentages aren’t the same as those of GSS, but the generational trajectory is.

Pew Religious Landscape Study from 2023–24, showing LDS

retention by birth decade. (Data analysis and graph by Benjamin Knoll)

To recap: Both studies show that more people are leaving the LDS church in the United States, and that disaffiliation is higher for younger Saints than for older ones. And both of these studies are respected enough by the church that it has cited other findings from them in its own media stories and press releases, whether it’s noting recent GSS results that married parents are happier than other people or reporting Pew’s research about how Americans feel about Latter-day Saints.

I want to make one final observation. Both of these same surveys clearly show that those Mormons who remain identified with the church are often deeply religious. That’s true of LDS Gen Zers and millennials too: The ones who stay in the church are far more religiously devout than other Americans their age.

I’ll explore that more in the next column, but for now let me just say that more than one story can be true, even in the same data set.

It’s clear that at least in this country, many young people who grew up LDS are exiting the doors. That doesn’t mean it isn’t true that the church’s Institute program offering religious education and community for young adults is growing numerically across the globe. (Though Institute has also expanded its program parameters to include people up to age 35, which makes more people eligible, and has required students in the popular BYU-Pathway college-degree program to attend Institute.)

That also doesn’t mean it isn’t true that the missionary program is growing. Thousands of young people appear excited to serve, which is great news for the church. And as I’ve stated elsewhere, last month’s decision to lower the missionary age to 18 for women is a long-overdue genius move. In the sociology of religion, the most vulnerable time for people to leave religion is still the period of late adolescence and their early 20s. Our Next Mormons Survey research confirms that’s true in the LDS context. In the 2016 NMS, the median age for people to leave the church was 19, and in the 2022–23 NMS it was 18.

So, anything the church can do to keep young women in the religion’s pipeline, without a critical gap after high school, could be beneficial.

My follow-up column will look more closely at young adults who stay LDS and how they compare to other Americans their own age religiously and to previous generations of LDS young adults. Spoiler alert: Although the data is clear that more young adults are leaving Mormonism than in the past in the U.S., what we know about the ones who stay is a bit murkier. In some ways, those who stay look quite religious, and in other ways, they are giving church leaders a lot to worry about.

Alex Bass and Benjamin Knoll contributed data analysis to this report.