Carla Blank in 2019, at the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition, “Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done,” standing next to the poster for “Dance by 5,” an April 20-21, 1965 Judson Memorial Church performance including works by Carla Blank and Suzushi Hanayagi, Meredith Monk, Carolee Schneemann, and Elaine Summers. Poster design by Isamu Kawai. (Photo by Tennessee Reed)

Ishmael Reed: I’ve been reading these jazz biographies, where aspiring jazz musicians go to a concert and they see some great performer, and they either want an instrument like the one they have, or they want to imitate them. Now, when you were a child, did you ever go to some concert where you saw a great dancer and that inspired you?

Carla Blank: Oh, absolutely. Of course, Martha Graham. She was a great influence on my life and on my development as a dancer. She came to my hometown of Pittsburgh a number of times over the years. First in Pittsburgh or later in New York, and the American Dance Festival in New London. I saw her perform with her company in many of her signature works—Appalachian Spring, Every Soul is a Circus, Letter to the World, El Penitente, Night Journey, Diversion of Angels, Acrobats of God, Clytemnestra, and on and on. She was a woman who was widely recognized for her greatness during her own lifetime. Very unusual, especially for a dancer, and not even a ballet dancer but a modern dancer! I saw her give a speech at some sort of lady’s luncheon in Pittsburgh, where I was born and raised. I don’t remember what the occasion was—perhaps it was a fundraiser, necessary to afford to bring her company to town. There she was, elaborately dressed in a fitted brocade sheath, high heels, and satiny opera gloves that extended above her elbows, stating in her imposing manner her aphorisms, sayings she was famous for, one after the other: “Everyone is born with genius, but most people only keep it a few minutes” was a favorite. Another was: “There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and will be lost.” And of course her belief that dancers are the “acrobats of God.”

Ishmael Reed: Your mother took you to these places?

Carla Blank: We went as a family, but she was the driving force behind all this. Well, my mother and the organization she belonged to, where I was trained as a young dancer. It was called Contemporary Dance Association, and they were housed in the Arts and Crafts Center as one of a community of ten arts groups. There my teachers were Rose Mukerji and Rose Ann Lohmeyer, who both had attended summer dance workshops at Bennington College in the 1930s and early 1940s, where the then-greats of modern dance, including Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman and Hanya Holm were in residence.

Ishmael Reed: So they brought those techniques to their training in Pittsburgh.

Carla Blank: Yes, that was basically how I was trained, in the early classic modern dance techniques, rather than the way that much of my generation was being trained by the 1950s and 60s, which mixed in ballet training—something not allowed by the old school revolutionaries. Then I also saw concerts by other dancers who influenced me, like Balasaraswati who practiced the Bharatanatyam style of classical Indian dance, and Uday Shankar, who fused classical traditional Indian dance traditions with European theatrical techniques.

Ishmael Reed: Is he related to the musician Ravi Shankar?

Carla Blank: He was Ravi’s brother, and, if I am not mistaken, they would appear together, using the great raga improvisational form to structure their performances. And there was another Indian company who came to Pittsburgh a few times, who presented the traditional Kathakali style, a more martial arts based form danced by men, with elaborate masks, voluminous multicolored costumes and drums. Great flamenco dancers and their companies stopped in Pittsburgh also. I especially remember Carman Amaya and José Greco. And Pearl Primus. She came to Pittsburgh twice with, as I remember, a concert of solo pieces influenced by her anthropological studies in Africa and the Caribbean. I’d never seen anyone jump like that. Actually, there weren’t many modern dance touring companies when I was growing up in the forties and fifties—maybe six or seven companies. And because the Contemporary Dance Association sponsored many of them, sometimes dancers would stay at our home.

Ishmael Reed: Like who?

Carla Blank: Like members of the Dudley-Maslow-Bales company, which was headed by Jane Dudley, Sophie Maslow, and William Bales. Sophie Maslow and Jane Dudley had been featured dancers in Graham’s company. Bales appeared with the Humphrey-Weidman company. As I remember, a lot of this company’s work was based in folk tales and folk songs. I think that’s where I saw Donald McKayle’s now classic Games for the first time.

Ishmael Reed: So your mother rented out rooms.

Carla Blank: Not rented, just hosted modern dancers as guests because she was part of the Contemporary Dance Association, which presented most of them in concerts. Because nobody had any money. The dancers and us. And so I was able to be up close and personal with these dancers, seeing their exhaustion, their dedication. Important, unforgettable life lessons.

Ishmael Reed: What other companies? Did any members of Jose Limón’s company stay at your house?

Carla Blank: I’m not sure if any company members stayed at our home, but I remember ironing their costumes for the Moor’s Pavane. And being surprised at the weight of the fabric of those costumes.

Ishmael Reed: How old were you?

Carla Blank: Maybe ten, twelve, something like that. Limón choreographed the piece as a quartet, based upon Shakespeare’s Othello. Limón danced Othello, Louis Hoving danced Iago, Betty Jones danced Desdemona, and Pauline Koner danced Emilia. Set to Henry Purcell’s music, that great dance is considered one of the classics of modern dance. It influenced me, certainly.

Ishmael Reed: Your mother, did she pay for your lessons?

Carla Blank: Fortunately, she managed to find scholarships for me. I was a gifted child who just loved to dance. Starting when I was very young, I would dance when any music played on our record player. By the age of five, I was given scholarships to study modern dance, plus piano, and then violin, and by third grade I left public school to attend Falk Elementary School, an experimental private school attached to the University of Pittsburgh’s Education department. Falk needed girl students, so two of my sisters and I benefitted from scholarships, which made it possible for us to go there. I spent much of my time at Falk collaborating with the music teacher, Mimi Kirkell, and other students in the school, making multidisciplinary performance works. That was a big influence on how I have lived my performance life. And other tuition waivers or scholarships continued throughout my college years. By the time I graduated in 1963, the once revolutionary dance styles I had studied had become the academy, so I sought out the next revolution, which in New York City was happening at Judson Memorial Church.

Ishmael Reed: And you were part of that movement. So who were some of the people you met? Dancers who are now well known?

Carla Blank: For instance, my junior year of college I transferred to Sarah Lawrence College where two students who are well-honored artists were in classes with me: dancer/choreographer Lucinda Childs was one year ahead of me, and composer/ vocalist/choreographer/director/filmmaker Meredith Monk was one year behind me. They have Judson connections. A dancer in Paul Taylor’s company for many years, Carolyn Adams, was also one year or two years behind me, I’m not sure which. And then Beverly Emmons, who was one year behind me, became a major lighting designer for dance and theater.

Ishmael Reed: What was the first time you went to Judson? Do you remember?

Carla Blank: I thought I attended my first choreography workshop in the fall of 1963, following my graduation from college, but when I checked the dates in dance scholar Sally Banes’ Terpsichore in Sneakers and Democracy’s Body, she sets the last Judson workshop session in Fall, 1964. (Musician Robert Dunn started leading these workshop sessions in the fall of 1961.) Other than a concert by Judson participants I attended that summer of 1963, this was what I remember as the beginning of my association with Judson. The session was located in the East Broadway loft of Judith Dunn, who at the time was married to Robert Dunn. Among those I recall being there were Judith Dunn, of course, Yvonne Rainer, Robert Morris, Elaine Summers, Sally Gross, Steve Paxton, Deborah Hay, maybe Alex Hay and Tony Holder, and Lucinda Childs who did a spectacular piece, Street Dance, walking along the sidewalk across the street from the loft as we observed from a window above, while a recorded monologue of her voice described exactly what she was seeing, coordinated by a clock-timed score, down to the second. I think that’s where I met Elaine Summers and Sally Gross, with whom I performed and became friends. I can’t remember Robert Dunn’s weekly assignments, but it was very fortunate that I was able to have that workshop experience.

Ishmael Reed: Well, Marcel Duchamp was Judson. He killed modernism. I mean, his ideas influenced your directing of those elderly residents at the Home for Jewish Parents in Oakland—walking as dance, placing their daily life on stage for their families to see. That’s life as art.

Carla Blank: Right. The two performance projects I directed at the Home remain among my all-time favorites.

Ishmael Reed: How many scores did you write and perform at Judson?

Carla Blank: I think I performed at Judson around twelve times or so between 1963-1966. One big event was Concert #13, performed Nov. 19-20, 1963, whose program was titled “A COLLABORATIVE EVENT with ENVIRONMENT by Charles Ross.” Turnover was my score within that event, in which I directed the women performers to overturn a huge, very heavy, welded steel pipe sculpture by Ross. I also performed in another piece during that program, Room Service, a piece credited to Rainer and Ross, in which three teams of three people each, in the manner of the game Follow the Leader, moved around the Judson sanctuary amidst the tires, mattresses, welded sculptures, ropes, ladders, metal folding chairs and other stuff that Ross had assembled. Sally Gross and I were on the team that Yvonne led. In 1964 there was a big intermedia piece directed by Elaine Summers, Fantastic Gardens, where I performed a ballroom style couple dance with Rudy Perez, costumed in a slinky black ankle length slip dress. Another event I danced in that year that has been talked about a lot, maybe because it was such a campy outlier to the prevailing Judson aesthetic, was a story ballet choreographed by Fred Herko: Palace of the Dragon Prince, set to music by Berlioz and St. Saens. Then besides performing a couple of my own improvised pieces, mostly best forgotten, Sally and I performed two duets in 1964—Untitled Duet and Pearls Down Pat—plus I improvised in one of her own pieces, In Their Own Time, and collaborated with Elaine Summers on Film-Dance Collage. In 1965 I performed one solo improvisation, Untitled Chase, for Arthur Sainer, a playwright who was also a Village Voice theater critic at the time, and somewhere along those years I was in pieces by Aileen Passloff and Meredith Monk and happenings by Ken Dewey and Al Hansen, although Hansen’s took place at a private estate on Long Island which included a swimming pool. For me, the most important work I created and performed at Judson was Wall St. Journal, in 1966, which was my fourth collaboration with Japanese dancer Suzushi Hanayagi. It was motivated by two real life events: the death of Suzushi’s two-week-old baby girl and the then-expanding Vietnam War. It revealed to me how I needed to find my own ways of working. To tell the truth, for me, a lot of what went on at Judson was good to experience as a performer, but as audience, was better to contemplate in theory. I was never completely in love with having abstraction be the sole motivation for my work—most often there was some narrative going on in my mind too—what you might call “social realism” behind the abstraction.

Ishmael Reed: You dealt with politics which critics viewed as a no-no during that time. A lot of these critics were former radicals themselves but got scared into art for art’s sake by McCarthy. What was the first play that you directed?

Carla Blank: I think it might have been a medieval mystery play, The Second Shepherds’ Play, that was performed by high school girls, my students at Convent of the Sacred Heart in San Francisco. That school, built like a castle in 1915 by James Leary Flood, one of San Francisco’s robber barons, had a beautiful wood-lined space similar in design to early Renaissance theaters, where I taught dance and drama classes from 1974-1976, so the setting was already there for the taking.

Ishmael Reed: And so did you get the hook for directing then?

Carla Blank: Yes, it was a fresh challenge, partly inspired because my students were more interested in drama than they were in dance. That high school was probably the first place where I really worked on developing how to direct plays.

Ishmael Reed: Didn’t you know a lot about directing before then…?

Carla Blank: Of course I had been directing myself and other people in dance works. And from a very young age, I saw a lot of theater, read a lot of plays, studied mime at Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University) with Carlo Mazzone, and Dalcroze eurhythmics with Cecil Kitkat, and took courses in theater theory and design with Wilford Leach and scene study with Charles Carshon at Sarah Lawrence. Actually, the way I was trained as a dancer was similar to the way actors are trained in the Stanislavski method. When I choreographed my first big solo to Ravel’s Pavane for a Dead Princess, around the age of thirteen, Rose Mukerji coached me by having me tell her what I was thinking: what is this, why are you doing that? For every action in the dance. That approach, which must have been consistent with Graham’s, was really the polar opposite of how, for instance, people worked at Judson, where you might be variously asked to execute a task, or follow a list of rules, like rules of a game, or decipher a visual score like a musician would interpret a musical score.

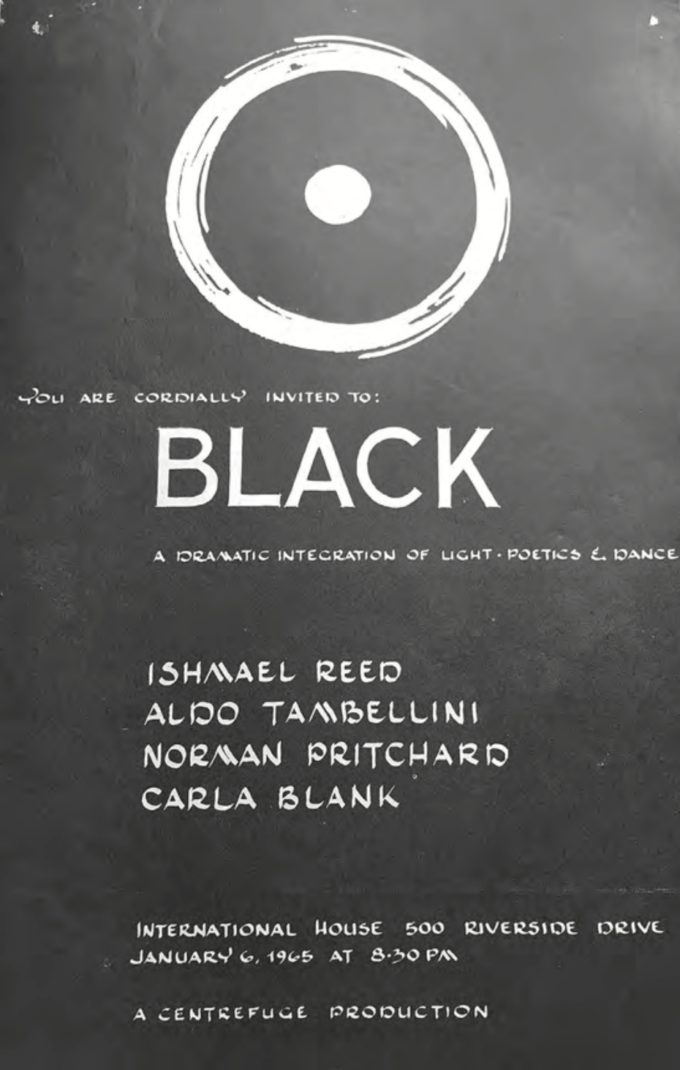

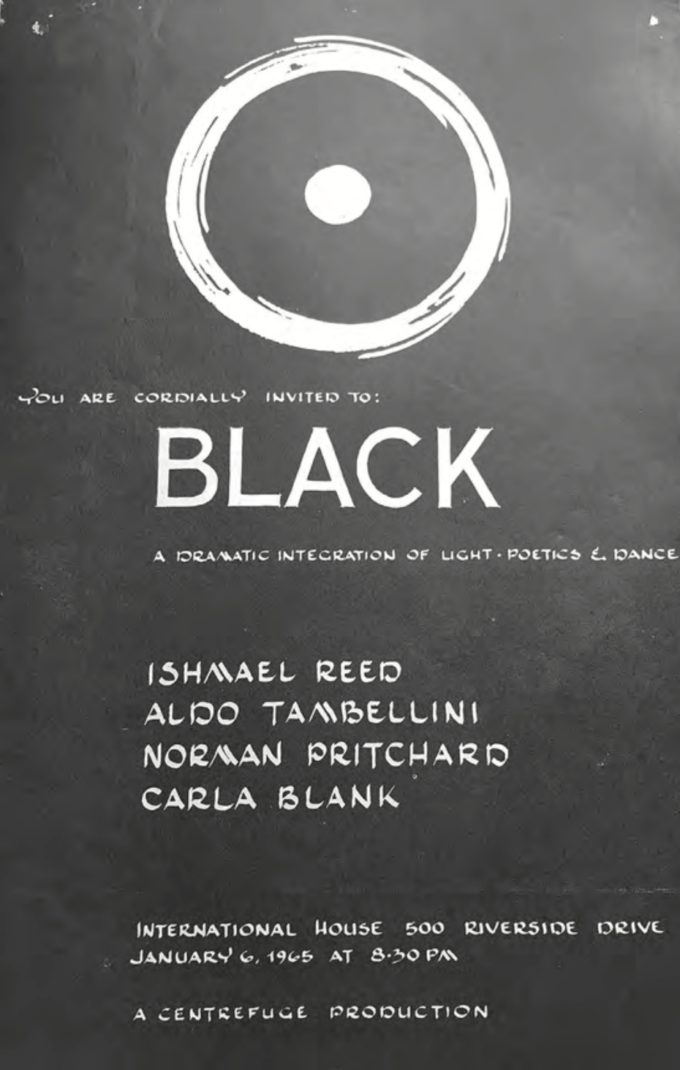

Poster by Aldo Tambellini for a multi-disciplinary performance collaboration with visual art projections by Aldo Tambellini, poetry by Norman Pritchard and Ishmael Reed, and dance by Carla Blank. Performed at Columbia University’s International House and the Bridge Theater, in 1965.

Ishmael Reed: So you’ve directed a bunch of stuff since then?

Carla Blank: Oh yes—My training to direct theater works was mainly through on the job by the seat of my pants style training— figuring it out with non-professional actors in schools or community arts programs. I read a lot of books by directors, taking clues from what I could glean from their methods that would apply to whatever I was directing. I studied Viola Spolin, especially for ways to warm up actors and develop an ensemble out of a pick-up group Constantin Stanislavski, Richard Boleslavsky, and various American Method style directors for creating back stories and motivations Antonin Artaud and Bertolt Brecht for their alienation and critical techniques and those experimenters who were being watched in the 60s and 70s like Jerzy Grotowski, Joseph Chaikin, Augusto Boal, Tadashi Suzuki. Many of the pieces were original works, written by the students, which is a way I really enjoy working. And some were existing plays like Bertolt Brecht’s He Who Says Yes, He Who Says No, Twelve Angry Jurors by Reginald Rose, Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, The Day Room by Don DeLillo, Jean Giraudoux’s The Madwoman of Chaillot, Agatha Christie’s The Mouse Trap, and David Ives’ one act plays. Plus you helped write a play for the Berkeley high school students, Poppa Bizzard’s Feast, weaving together tales that all the participants had created for themselves as an animal character. And a high school production of your play, Mother Hubbard, convinced Miguel Algarin to bring it to the Nuyorican Poets Café as a musical. Later, I again directed a non-musical Mother Hubbard, for a literary conference in Xiangtan, China, in a production performed in English by Chinese college students.

Ishmael Reed: But some of these works were viewed as though you were doing adult theater, reviewed in the newspapers. In the San Francisco Chronicle.

Carla Blank: Yes. When I was teaching at Arrowsmith, a private Berkeley high school that no longer exists, I was often able to arrange to have these works mounted in U.C. Berkeley’s well-appointed theaters, which were located a short walk from the school, besides being allowed to borrow items from the U.C. drama department’s great cache of costumes and set pieces. Those spaces and design elements helped frame the productions to their advantage. And then there were the works I co-directed with Jody Roberts for the Children’s Troupe, the performing arm of our non-profit after-school program where the performers ranged from five to eighteen years of age. We and the children created original works between 1979-1992, often in collaboration with other adult artists. The performances happened at libraries, arts festivals, parks, senior citizen centers, shopping malls, schools, theaters, and museums. We even opened an AIA national convention with a performance called “Horse Ballet” in San Francisco’s Union Square, inspired by the equestrian spectacles in sixteenth and seventeenth century European courts. (There is a little more information about horse ballets in my book review, “Apollo Could Be a Bitch: Jennifer Homans’s Coffee Table Ballet.”) These were some of the most exciting projects I ever worked on. Nothing like the magic of young performers. My directing wasn’t limited to working with children and young adults. I continued to work with adults, sometimes trained professionals and sometimes not. From 2003-2011, I worked as dramaturge and director of The Domestic Crusaders by Wajahat Ali, following a day in the life of a Pakistani-American family. From 2008-2010 I worked with director/designer Robert Wilson on KOOL-Dancing in My Mind. I write about that work in my essay, “Suzushi Hanayagi in Mulhouse.” In 2013, I lived in Ramallah, Palestine, co-directing Palestinian and Syrian actors in an Arabic translation of American Philip Barry’s play, Holiday, at the Al-Kasaba Theatre and Cinematheque, which presented this production in partnership with the American Consulate General in Jerusalem. My essay, “A Jew in Ramallah,” recalls that experience. From 2013-2017 I was dramaturge and director of an international cast of dancer/actors and musicians in Yuri Kageyama’s News From Fukushima: Meditation on an Under-Reported Catastrophe by a Poet. And most recently I directed two productions of your plays Off-Off Broadway at Theater for the New City: The Slave Who Loved Caviar,” which I also choreographed and a “Living Newspaper” styled play, The Conductor.

Carla Blank giving notes to the cast of The Conductor, a play by Ishmael Reed. Sitting on the stage set, in the process of being prepared for the premiere run at Off-Off Broadway’s Theater for the New City are, left to right: CB with open notebook, Emil Guillermo, Imran Javaid, Kenya Wilson, and Laura Robards. (Photo by Ishmael Reed)

Ishmael Reed: And then, you started writing books, beginning with Live On Stage!, which was based on your experiences with children, right?

Carla Blank: Yes, I think that was a twenty-year project as I began writing about my teaching experiences in the late 70s or early 1980s and it eventually evolved into a two-volume textbook, co-authored with Jody Roberts, to help classroom teachers integrate arts into their basic curriculum. The anthology mixes performing arts traditions from around the world, making cross disciplinary connections and generally expanding concepts of theater training to include traditional and experimental techniques. Everything was grounded in classroom and workshop experiences. Besides being used in schools around the country, it was officially adopted in four states: Tennessee, Idaho, Mississippi, and North Carolina, all places that I have barely stepped foot in, so that was amazing.

Ishmael Reed: And then you did Rediscovering America, the Making of Multicultural America, 1900-2000.

Carla Blank: That timeline book was inspired by my students at U.C. Berkeley, where I taught a course in twentieth-century art innovations on and off during the 1990s. When I realized many of the students didn’t have much background in events that surrounded developments in the art world, I put together a timeline as part of their course materials to help them better understand the governmental, technological, and social changes that were occurring along with the artistic innovations. The timeline expanded as I continued to teach the course. Students suggested innovations they felt important to include, as eventually, once I signed a contract to write the book, did members of the Before Columbus Foundation, who also wrote the introductions to each decade, and many scholars and artists who wrote sidebars and served as consultants. That was about a ten-year project. The first essay in this collection, “Postmodernism,” was written for Rediscovering America.

Ishmael Reed: Next was the architecture book, Storming the Old Boys’ Citadel: Two Pioneer Women Architects of Nineteenth Century North America.

Carla Blank: Another ten-year or so project. You provided the impetus for that book, when you returned from a trip to Buffalo with a tale about how you noticed a plaque on the outside of a downtown hotel saying that it had been designed by Louise Blanchard Bethune, the first professional woman architect in the United States, who started practicing before the turn of the twentieth century. You had never noticed the building while growing up in Buffalo, and you wondered how it had fallen into such a state of  disrepair, given this architect’s history. Since I had never heard of Bethune, I began researching her life. As a woman working in the male-dominated field of architecture, Bethune’s story appeared very similar to stories I had learned about women scientists and other twentieth-century women professionals while writing Rediscovering America. It sounded like an important story to tell. Once Robin Philpot, publisher of Baraka Books, expressed interest in publishing it, Canadian architectural historian Tania Martin agreed to join the project. She wrote about Mother Joseph of the Sacred Heart, a Québec-born nun who is credited with architectural works built in the Pacific Northwest, following her arrival in the Oregon Country in 1856. Three essays relate to how this project evolved from 2006-2014: “Neglecting A Grand Old Lady,” “How Buffalo’s Hotel Lafayette Went from Fleabag to Fabulous,” and “Storming the Old Boys’ Citadel.”

disrepair, given this architect’s history. Since I had never heard of Bethune, I began researching her life. As a woman working in the male-dominated field of architecture, Bethune’s story appeared very similar to stories I had learned about women scientists and other twentieth-century women professionals while writing Rediscovering America. It sounded like an important story to tell. Once Robin Philpot, publisher of Baraka Books, expressed interest in publishing it, Canadian architectural historian Tania Martin agreed to join the project. She wrote about Mother Joseph of the Sacred Heart, a Québec-born nun who is credited with architectural works built in the Pacific Northwest, following her arrival in the Oregon Country in 1856. Three essays relate to how this project evolved from 2006-2014: “Neglecting A Grand Old Lady,” “How Buffalo’s Hotel Lafayette Went from Fleabag to Fabulous,” and “Storming the Old Boys’ Citadel.”

Ishmael Reed: You’ve performed as a jazz musician. So now you have been heard internationally all over Europe and in Japan as a violinist.

Carla Blank: I was trained as a classical violinist, and still need to have a score to read as I don’t improvise. I have heard the early jazz violinists didn’t improvise either.

Ishmael Reed: Veteran jazz musicians at the Sardinia Jazz Festival admired your tone, and the CD The Hands of Grace on which you perform is a best seller in Japan. You also appeared on the CD For All We Know, featuring David Murray and Roger Glenn. Tell me about the essays in this book.

Carla Blank: Yes, the twenty-three essays in this book were written over the past twenty years. Like those books I wrote and edited that we’ve talked about here, many were inspired as a way to bring attention to events and individuals who have been forgotten or widely neglected in most historical and critical accounts. Or who I felt just deserved more attention. They mainly appeared in the Wall Street Journal, ALTA Journal, and online at CounterPunch and Konch magazine, and in published anthologies.

Ishmael Reed: How old were you when you got your first award nomination down there at the Los Angeles Press Club?

Carla Blank: Those happened in 2022 and again in 2023. So I was 81 and 82.

Ishmael Reed: You are competitive with some of the top journalists in the country.

Carla Blank: Funny.

Ishmael Reed: So what’s next? I mean, we’ve gone through about four careers here.

Carla Blank: Yes. I’ve been directing your newest play, The Shine Challenge, 2024. And I have a couple more book projects in mind.

Published with permission from Baraka Books.