Trump to Venezuelans: Give Me Your Oil, Obey My Commands or Die!

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

In the aftermath of President Trump’s deadly military attack on Venezuela and his abduction and rendition of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia, Trump is now giving the Venezuelan Chavista regime a simple choice: Obey my commands and give me your oil, or die from death by starvation and illness.

According to an article in the Washington Post, “Trump administration officials say the Venezuelan government only has a few weeks before it would ‘go broke’ if it doesn’t ‘play ball.’” Playing ball obviously means obeying Trump’s commands and giving him some of Venezuela’s oil.

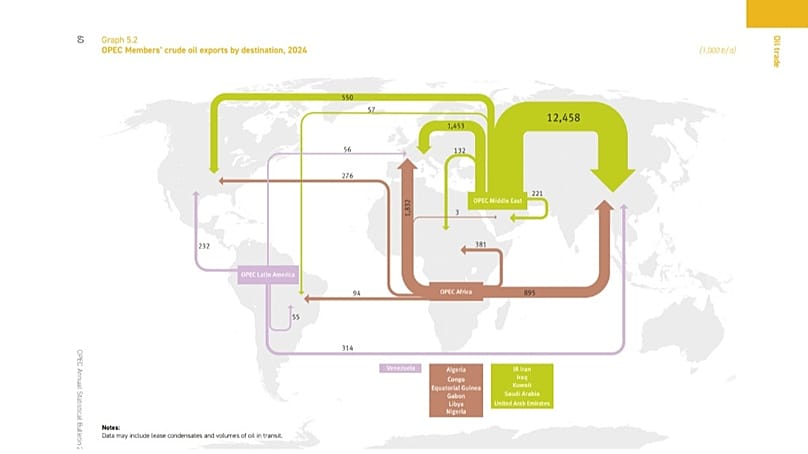

In what amounts to a siege military strategy, Trump and the U.S. national-security establishment (i.e., the Pentagon and the CIA) have essentially imposed a total blockade on oil shipments out of Venezuela, including the piratical seizure of ships containing Venezuelan oil destined to other countries, such as Cuba, Iran, and China, which are considered to be official enemies, adversaries, or rivals of the U.S. Empire.

Since Venezuela depends entirely on oil revenues, Trump’s siege strategy is obviously designed to plunge the nation into a graver economic crisis involving massive chaos, starvation, illness, and violence as people scramble to survive — unless the Venezuelan Chavista regime decides to “play ball” by obeying Trump’s commands and giving him some of the country’s oil.

Might some Venezuelans die in this chaos? ? Sure, but who cares? After all, who cares about the U.S. assassinations of those hundred defenseless people in those little boats who were accused of violating U.S. drug laws hundreds of miles away from American shores? Who cares about those 100 people who were killed as part of Trump’s abduction raid against Maduro? Who cares about the 8 million Venezuelans who have fled the country in the effort to survive the vise of Chavista socialism and brutal and deadly U.S. sanctions?

Moreover, if any Venezuelan citizen tries to save his life by entering the United States without the official permission of the U.S. government, all that U.S. ICE agents and Border Patrol agents have to do is take these tattooed gang members and invaders into custody and force them back into Venezuela to die — or maybe just send them to El Salvador for torture, indefinite incarceration, or execution — or maybe even just murder them in cold blood on the streets of some American city.

What difference does it make? No difference at all. American citizens can just keep nonchalantly going about their lives — going to work, going on vacation, going to their weekly religious services, and, of course, thanking the troops and CIA officials for their service.

I can’t help but wonder whether Trump’s, the Pentagon’s, and the CIA’s siege strategy is inspired by the same siege strategy that was regularly employed by the Roman Empire against its enemies, adversaries, and rivals. Whenever a recalcitrant opponent — that is one that refused to submit to Rome’s commands — would ensconce itself in a well-fortified castle, Roman imperial forces would simply surround the fortress and prevent any relief from being brought into the castle. The idea was to give the enemy a choice, the same choice that Trump is giving the people of Venezuela: Submit to our control or die from starvation and illness.

It proved to be a very effective strategy. Faced with food shortages, contaminated water, and epidemics, most defenders would surrender before the walls of their fortress were breached. The Romans would give them an incentive to surrender sooner rather than later by imposing penalties for waiting too long — e.g., execution of leaders, survivors sold into slavery, and a certain number of resisters killed.

And then there is the famous story of the Roman siege of Masada, an impenetrable fortress that was inhabited by around a thousand Jewish men, women, and children who refused to comply with Rome’s commands. Employing their siege strategy, the Romans completely encircled Masada and prevented any relief from entering the fortress.

The leader of the resistance gave a speech arguing that death was preferable to slavery, torture, or execution. When the Romans ultimately breached the walls of the fortress, they found most everyone dead.

Will Venezuelans decide to “play ball,” obey Trump’s commands, and give him Venezuela’s oil? Or will they follow in the footsteps of the Masada resisters? My hunch is that they will decide to “play ball,” and who can really blame them? But remember what is ultimately important about all this death, suffering, mayhem, violence, and coercion: It’s all making America great again.

This first appeared on Hornberger’s Explore Freedom blog.

Chronicle of a Foretold Coup: The Attack on Venezuela and the Narco-Terrorism Fairy Tale

Photograph Source: Official White House Photo by Molly Riley – Public Domain

Current developments in Venezuela may appear to be unfathomable—until one recalls the long history of imperialist interference in Latin America and the Caribbean. The events of the first week of January constitute an escalation of a long-standing campaign to overthrow the Bolivarian Revolution and resume control on the country with the largest known oil reserves in the world. The emerging world order and the strengthening of international organisations non-aligned with the interests of the United States (US) rush the US to increase the pressure on the Latin American region.

Latin America and the Caribbean are deeply marked by US imperialism. In the 200 years since the Monroe Doctrine (1823), the US military has carried out more than 100 interventions, invasions, and coups in Latin America and the Caribbean. In the 1970s, the CIA carried out a series of military coups throughout the region to overthrow left-wing and independent governments. In a secret program known as Operation Condor, the CIA worked closely with military dictators to suppress left-wing activists and prevent the rise of communism among the local populations.

Neoliberal policies implemented through the coup regimes and after—and under the influence of the Washington Consensus in the 1990s—deeply affected economic development in the region. As a result, 50 million people in Latin America fell into poverty from 1970 to 1995, and the external debt tripled from $67.31 billion (1975) to $208.76 (1980), 60 percent of which was public debt, further stifling the possibility of economic development and pushing the countries into debt-traps. The effects of privatization and the destruction of the industrial structure continue to this day.

The popular leaders that emerged from people’s rebellions against the neoliberal regimes and led the Progressive Wave in the Latin American region during the beginning of the 21st century were targeted by the CIA. Venezuela constitutes one of such cases.

Following President Hugo Chávez’s inauguration in 1999, the United States systematically attacked Venezuela. After repeated refusals to submit to US leadership, in April 2002, supported by a sector of the Venezuelan military, the US carried out a coup d’état and kidnapped President Chávez. The Venezuelan people took to the streets en masse and halted the attack. The events of that April forced US imperialism to change its strategy and opt for a prolonged hybrid war aimed at weakening popular support for the Bolivarian Revolution.

The hybrid war on Venezuela consists primarily of economic sanctions and embargoes, and the persecution of popular leaders, along with the funding of anti-Chavista propaganda and organisations, and the development of paramilitary groups to create an atmosphere of internal destabilization. In addition to the multiple assassination attempts, in 2019, the US did not recognise the electoral results, and backed the opposition candidate Juan Guaidó as president of Venezuela. The bombing of Caracas and the subsequent kidnapping of President Nicolás Maduro and Cilia Flores on 3 January 2026 are the most recent blow in a series of systematic and increasing attacks spanning more than 20 years.

Trump openly declared that the US attack on Venezuela is about oil. Nonetheless, US officials, including Trump, have offered two other unconvincing reasons: the migration crisis and narco-terrorism.

Migrants and Drugs

Economic sanctions and the blockade against Venezuela caused a collapse in the population’s living conditions, generating shortages, accelerated impoverishment, and large-scale forced migration. The departure of more thanseven million people over the past decade is due to the economic war.

Venezuelan migration has been used as a political instrument, presented as proof of the failure of socialism and the revolutionary project, while the sanctions responsible for the forced migration have been rendered invisible. Many Venezuelan migrants were initially classified as “political refugees” in the countries to which they migrated, reinforcing the narrative that they were fleeing a dictatorship and thereby legitimizing the imposition of further sanctions, creating a vicious dynamic. Venezuelan migration has also been used as a warning aimed at potential left-wing voters in Latin America.

Through hardline immigration enforcement policies promoted during the second Donald Trump administration, migrants have been criminalized: they are being rounded up, detained, and—some of them—forcibly transferred to the CECOT mega-prison in El Salvador.

The criminalization of the migrant as a narco-trafficker fuelled the construction of a narrative about Venezuelan cartels. This led to the accusation that Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro was a leader of gangs known as Tren de Aragua or the non-existent Cartel of the Suns. The idea of drug trafficking provided the justification to attack small boats, 36 of them sunk through 35 illegal bombings that killed 115 people. It was this idea of narco-terrorism that was used to justify the attack on Venezuela on 3 January.

Trump brought together the War on Terror (the 2001 Patriot Act) and the War on Drugs (stretching back to the 1970s) to create this idea of ‘narco-terrorism’ and build legitimacy in the US for the attack on Venezuela not as a military invasion but as a police action. Trump now wants to extend this logic to Cuba, Colombia, and Mexico.

The attack on Venezuela came at a time when the country was slowly emerging from the worst of the social impact of sanctions. Economic recovery in Venezuela amid those sanctions occurred in a context marked by the emergence of the BRICS and the tightening of commercial and political relations with China, Iran, and Russia, which made it possible to smoothen the consequences of the US sanctions. At the same time, the deep scarcity crisis, particularly harsh in a country historically structured under a rentier model dependent on food imports, drove a reorganization of national agricultural production and food supply chains oriented toward building food sovereignty. In this process, the communes, together with the emergence of new national companies dedicated to producing food and other essential goods, energized the Venezuelan economy and enabled a rapid recovery after the crisis induced by the sanctions.

An organised response to the interference

The collective response to economic coercion is in line with that of recent events. The people took to the streets: thousands of people in Caracas, in rural areas, and in other cities mobilized for the release of their president and in rejection of a US military intervention, backing the Bolivarian militias, the police, the Army, and the government. This resistance has been overlooked in international media.

Finally, the swearing-in of Vice President Delcy Rodríguez as the head of the government, together with the presence of the ambassadors of China, Iran, and Russia, as well as the installation of the National Assembly with the presence of Nicolás Maduro’s son, demonstrate that the Bolivarian Revolution is not defeated and that speculation about internal betrayals lacks concrete basis.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Venezuela: The final word

First published in Spanish at Saber y Poder. Translated by LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal.

The deafening explosions that shook Caracas, La Guaira, Higuerote and Puerto Cabello in the early hours of Saturday, January 3, were naturally followed by widespread confusion. A clear, moonlit night provided the backdrop for the infamous spectacle: for an hour, rockets streaked across our airspace and crashed, criminally and with impunity, in different parts of the capital city and the central coast, leaving a trail of death and destruction in its wake, as would soon confirm. A few hours later, the invading force was boasting about its achievements: it had proceeded to kidnap the head of state, Nicolás Maduro, along with his wife, Cilia Flores.

A week later, it is worth recording the popular reaction during those early hours of Saturday morning following the consummation of this imperial outrage. The streets were filled with calm, expectant silence, and a sense of mourning. It was a silence that was difficult to interpret, hence the imperative to try, even at the risk of misunderstanding.

It was not the complicit silence of those who were awaiting such an outcome or something similar. It was not the cautious silence of those who perhaps wanted to wait for further news before celebrating. Nor, it must be said, was it the silence of those who were eagerly awaiting a call to arms. All of the above was no doubt in the mix. But the general atmosphere resembled something more akin to mourning for a humiliated homeland. Mourning for our boys killed in the line of duty. Mourning because things should not have come to this.

It may be a mourning that befalls any people as an inalienable right, when they realise that in the worst of times their destiny is not in their hands.

A tranquility, a silence and a mourning that, far from signifying consent with what had happened, spoke of a deep-rooted discontent that finds no outlet for expression.

Today, as demands and calls for restoring our violated sovereignty multiply — as they should — we should at least take the time to understand the silence of those with whom sovereignty resides. Something similar can be said about the necessary calls for unity: this is not the first time that a few issue a call for the unity of a few, leaving the majority aside. This is not the time to reprimand those who ask questions and demand answers. It is not the time for naive and cynical calculations. At such a crucial moment in our history as a Republic, we cannot afford such actions and omissions.

Recent events demonstrate that silence does not always mean consent. Those who talk a lot can give consent, and those who are not willing to give consent sometimes remain silent. The latter remain silent because there is no one to listen to them.

[US President] Donald Trump speaks and does not stop speaking. He rants, believing himself to be the master of the world. He speaks and speaks until he strikes, not to make his country great again, but because it never will be great again. He strikes, believing us to be so small that we will celebrate his gesture. The “new human race” that we are, as Simón Bolívar would say, looks at him askance.

The numbers also speak: after the invasion, the markets reacted euphorically, oil stocks rose, and the Caracas Stock Exchange celebrated. Meanwhile, you can be certain that there are no celebrations and no more money in the pockets of the popular majority.

And yet, what prevails is tranquility, a certain “meekness,” to quote [Venezuelan revolutionary] Alfredo Maneiro, because the imperial aggression has occurred — not by chance — at a historical juncture in which tempestuous popular protagonism is absent, unlike in April 2002, when the dictatorship supported by the US government succumbed in less than 48 hours. Because one wave has passed, and another, and another, and the drops of water that will be at the crest of the next wave today lie in the trough that separates it from the preceding wave. The Venezuelan people occupy the place of still water, an apparent calm: “If anyone wants to discover in this appearance the seeds of a possible, different, and future Venezuela, they will have to push it aside and look underneath. It has always been this way, it has always been true that the darkest hour of the night is the one that precedes the dawn.”

In this dark hour when the people (including our Cuban brothers and sisters) mourn their dead, they can call it whatever they want: “staying calm,” “transition” or “being in charge of Venezuela.” The Venezuelan people will have the final word and once again ride the wave's crest.

by Ted Snider | Jan 12, 2026 | ANTIWAR.COM

The United States decapitated the Venezuelan regime and is dictating policy in Venezuela, running the country like an American colony. But the regime remains in place. Washington has been forced to exercise its dominance overtly through thuggish economic and military coercion rather than covertly by installing the pro-U.S. opposition.

There are at least four reasons for this failure. The first is past failures. Many of them. Guillaume Long, a former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ecuador and currently a senior research fellow at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, told me that “regime change (meaning getting the pro-US opposition into power) failed in Venezuela, because there have been so many US-supported failed coup attempts in Venezuela in the last few years, that there is literally no one left to organize and support a coup attempt.” That means that to pull off complete regime change would have required a military uprising or coup in Venezuela that the U.S. could support. “The Venezuelan security apparatus,” Long says, “is too tight for that right now.”

The second is that the most recent failures of U.S. supported coups in Venezuela left the Trump administration feeling that the opposition was incapable of taking over the country. The Trump administration had consistently asserted that Nicolás Maduro was an illegitimate leader who had stolen the last election from the María Corina Machado led opposition. Following the capture of Maduro, Machado declared that “Today we are prepared to assert our mandate and seize power.” But if she was, Trump wasn’t. Trump spurned Machado, saying “it would be very tough for her to be the leader if she doesn’t have the support within, or the respect within the country. She’s a very nice woman, but she doesn’t have the respect within [Venezuela].”

That reversal and rejection “blindsided Machado’s aides” and “landed like a gut punch” for Machado. The Wall Street Journal reports that Trump was leery of the Machado led opposition “after concluding it failed to deliver in his first term.” The U.S. had broken Venezuela with sanctions that had reduced oil production by 75 percent, that led to the “worst depression, without a war, in world history,” and caused tens of thousands of deaths. They had, to a large extent, diplomatically isolated Maduro, and they had done everything they could to catalyze a military uprising. But the armed forces did not rise up, the people did not rise up, and the opposition failed to take power. The Trump administration assessed “the opposition overpromised and underperformed.”

“Senior U.S. officials had grown frustrated with her assessments of Mr. Maduro’s strength, feeling that she provided inaccurate reports that he was weak and on the verge of collapse,” The New York Times reports. They had become “skeptical of her ability to seize power in Venezuela.” After repeatedly asking Machado for her plan “for putting her surrogate candidate, Edmundo González, into office,” they came to the realization that she had “no concrete ideas” on how to achieve that goal.

The third reason is that Machado is too radical to unite the opposition and the people of Venezuela. She “represents the most hardline faction” of the opposition, William Leo Grande, Professor of Government at American University and a specialist in U.S. foreign policy toward Latin America, told me. Yale University history professor Greg Grandin says, Machado has “constantly divided… and handicapped the opposition” by advancing a “more hardline” position.

When Machado won the Nobel Peace Prize, Miguel Tinker Salas, Professor of Latin American History at Pomona College and one of the world’s leading experts on Venezuelan history and politics, reminded me that Machado supported a coup against a democratically elected government, was a leading organizer of the violent La Salida insurrection that left many dead, and endorses foreign military intervention in her country. She was a signatory to the Carmona Decree, which suspended democracy, revoked the constitution, and installed a coup president.

Machado has supported the painful American sanctions on Venezuela. According to The New York Times, this strategy lost her support among the people and the elite. The business elite were threatened by sanctions and had “built a modus vivendi with Mr. Maduro to continue working.” The general population were anxious to improve living conditions, and Machado’s message alienated them. But as Trump tightened sanctions, Machado “remained largely silent.”

Her loss of support led to the loss of control of the levers required to come to power. Leo Grande told me that Machado’s hardline approach made her “the least acceptable to the armed forces.” “Trying to impose her,” he said, “would be very risky.” Tinker Salas told me that Machado is both “unacceptable to the military and the police forces” and to the ruling PSUV party structure. “Her imposition,” he said, “would have been a deal breaker.”

A classified U.S. intelligence assessment came to the same conclusion. The CIA analysis recommended working with the vice president of the current regime over working with Machado. The assessment convinced Trump “that near-term stability in Venezuela could be maintained only if Maduro’s replacement had the support of the country’s armed forces and other elites,” which Machado did not.

The CIA briefed Trump that Machado’s surrogate, Edmundo González, who ran against Maduro in the last election, “would struggle to gain legitimacy as leaders while facing resistance from pro-regime security services… and political opponents.”

So, despite framing the regime change as, amongst other things, a defense of democracy and the removal of a strong man who had held on to power illegitimately, the Trump administration side lined the opposition they said won the last election and assessed that their aims in Venezuela were best achieved by working, through economic and military coercion, with the vice president and inner circle of Maduro’s government.

Ted Snider is a regular columnist on U.S. foreign policy and history at Antiwar.com and The Libertarian Institute. He is also a frequent contributor to Responsible Statecraft and The American Conservative as well as other outlets. To support his work or for media or virtual presentation requests, contact him at tedsnider@bell.net.

Hey, POTUS, Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt Ain’t No Ghawar

The Venezuela saga gets more cockamamie by the day. It turns out that the predicates for kidnapping the president of a country that poses no threat whatsoever to America’s Homeland security are about as threadbare (and even comical) as they come. For instance, did the DOJ writers of the superseding indictment of Maduro and his misses not turn bright red with embarrassment when penning this gem:

“Possession of machine guns and destructive devices” and “conspiracy to possess machine guns and destructive devices” in furtherance of the narco-terrorism and cocaine importation conspiracies.

WTF! For better or worse, the man was the president of a sovereign nation-state, and the very essence of such institutions is that they have all the guns or at least most of the big, really lethal ones such as military-style machine guns. So this amounts to an “excuse me for existing” charge, but also something even more to the point.

The definitions in section 924(c) on which this machine gun charge was based derive from the National Firearms Act of 1934 (NFA). The latter was passed during Prohibition’s aftermath to combat armed gangsters like Al Capone, John Dillinger and Baby Face Nelson – all of whom famously used Thompson sub-machine guns (“Tommy guns”) in the conduct of their day jobs.

Of course, Prohibition was a disaster for endless reasons, but among them was surely the fact that the bonneted ladies of the temperance societies ended up causing more people to be killed by the machine guns of the booze-running gangsters than were being felled by excessive fondness for Demon Rum. Likewise, the reincarnation of Prohibition in today’s War on Drugs generates far more maimed and dead collateral victims – especially in the case of cocaine – than the contraband drugs themselves.

That is to say, on its own the annual fatality rate among the nation’s 5 million cocaine users is a tiny0.1% or identical to the 0.1% fatality rate for the nation’s 178 million (now legal) alcohol users. Yet since the utterly misbegotten War on Drugs has forced cocaine dealers into the Al Capone-style criminal black markets and subjected them to massive law enforcement attacks and interdiction losses, it has driven the price of cocaine from $400 per pound in the coca fields to $54,000 per pound for customers on the retail streets in the USA.

In turn, these massively bloated prices make pure cocaine 500X more expensive than fentanyl compounded in backyard chem labs on a per dose (“high”) basis. So, not surprisingly, coke dealers adulterate their high-cost cocaine out of the brick with practically zero cost-baking soda, which imitates its color and texture. They then add tiny pinches of high-potency (and deathly) fentanyl to their retail dime-bags in order to maintain its potency.

Needless to say, this kind of dangerous adulteration driven by government-created black market economics does sharply reduce dealers’ cost of goods sold and enhances their net profits. But it also generates upwards of 20,000 deaths per year in the US owing to fentanyl-adulterated coke. That’s actually more than four times more deaths than caused by pure cocaine overdoses alone.

As we will show in Part 3, however, if cocaine production, transit and distribution were legal, the street price would likely plunge by more than 95%, thereby removing any incentive for (legal) dealers to adulterate their product with pure poison. Indeed, in a legal market there would be no economic incentive at all to adulterate in this manner; and the deterrent of massive wrongful death suits would ensure that CVS, Walgreens etc. sold only safe (pure) product.

Yet the Donald and his band of MAGA fools domiciled on the Potomac cheered when the Navy blew-up the cocaine carrying speedboats and then virtually wet their pants with excitement when he perp-walked into Federal court the now ex-president of a country that is just a 8% bit player in the black market cocaine trade that would not even exist absent modern day Drug Prohibition.

And we do mean, not exist. Back in the day when the FBI and DEA didn’t exist, either, peaceful commerce handled the nation’s cocaine needs. And it did so with nary a machine gun fired or a Federal drug bust that resulted in over-crowding in the nation’s far smaller, more modest jails. And the price wasn’t sky high either.

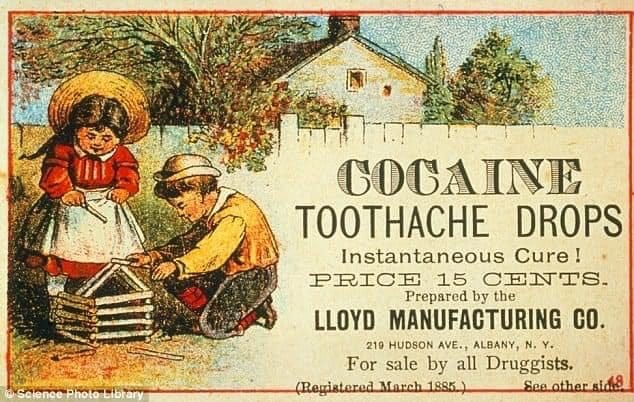

As shown in the 1885 ad depicted below, mothers needing to treat with their kids’ toothaches could get a whole bottle of the stuff for 15 cents!

That was peaceful commerce and productive capitalism. It also reflected the fact that 140 years ago Washington was still allowing the good people of Albany New York to decide for themselves what medicines, remedies and stimulants to consume in their daily lives.

1885 Ad For Cocaine Drops

So when we referred to the Donald’s cockamamie invasion of Venezuela, that’s exactly what we meant. Washington’s War on Cocaine is already unnecessarily killing 20,000 Americans per year via adulterated cocaine and thousands more in the course of moving contraband product through violent criminal syndicates from Columbia to the USA retail streets. So bringing the US Navy, Air Force and CIA to a War on Drugs which should never, ever have been declared 55 years ago is the very height of folly.

Yet, that isn’t all. We also have the alleged prize of Venezuela’s 303 billion barrels of oil reserve. But that ain’t nearly what its cracked up to be, either.

To hear the Donald and his minions tell about it, you’d think that someone discovered the equivalent of Saudi Arabia’s legendary Ghawar field in the Orinoco Belt of Venezuela. Alas, nothing cold be further from the truth.

The Saudi Ghawar field, the largest ever discovered, was indeed a black gold mine. In terms of sheer reserve volume, the original petroleum liquids in place thanks to Mother Nature was in the range of 170 billion barrels. Approximately 95 billion barrels have already been lifted since production commenced in 1951, but since the Ghawar field is so naturally prolific the ultimate recovery ratio is estimated at about 75%.

That’s because during geologic times oil migrated upward into anticlinal structures, preserving its lighter composition due to minimal biodegradation and favorable trapping mechanisms. Accordingly, the world’s largest conventional oil field in terms of recoverable reserves encompasses just 8,400 square kilometers in eastern Saudi Arabia, and consists of lighter crude oils trapped in deep carbonate reservoirs from Jurassic-era limestone formations.

That is to say, figuratively speaking the Saudi’s have merely needed to stick a straw in the ground in order to pump to the surface at low cost most of the oil deposited by Mother Nature over the course of the geologic ages. Consequently, after 75 years of oil essentially burbling to the surface owing to natural reservoir pressure – aided in recent decades by water injection – there are still 30 billion barrels of recoverable reserves left at today’s technology and prices.

Needless to say, the Orinoco Belt in Venezuela represents the opposite extreme of geology and therefore cost of production. In contrast to Ghawar, the Orinoco Belt spans about about eight times more territory at about 55,000 square kilometers in eastern Venezuela, which areas contains vast accumulations of extra-heavy crude oil trapped in shallow, unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs.

These deposits formed from ancient marine sediments that underwent biodegradation over millions of years under shallow surface waters, resulted in highly viscous, dense oils with low mobility. Representative of Orinoco oils, Zuata crude has an API gravity of around 9 degrees, classifying it as extra-heavy, with a viscosity that makes it behave more like tar than liquid oil at room temperature.

The crucial economic point is this: Zuata’s low gravity stems from the loss of lighter hydrocarbons through bacterial degradation in the reservoir, leaving behind heavier molecules rich in asphaltenes and resins. Hence, the metaphor of Mother Nature’s thievery.

Ghawar’s Arab Light crude, by comparison, boasts an API gravity of 33 degrees, making it medium-light and far more fluid. This higher gravity results from the field’s deeper burial and isolation from surface waters, preventing significant degradation and retaining volatile components that enhance flow properties.

Likewise, the sulfur content further differentiates these deposits. Zuata oils contain about 2.5% sulfur by weight, earning them the “sour” label due to hydrogen sulfide and other sulfur compounds formed during maturation. The Orinoco’s sulfur originates from organic-rich source rocks in a sulfate-rich environment, while Ghawar’s lower content reflects cleaner carbonate sources.

In terms of reservoir size and original oil-in-place (OOIP), both fields are supergiants, but as indicated their estimated ultimate recoverability rate is vastly different. While the Orinoco’s OOIP is estimated at over 1.3 trillion barrels, which gives rise to the image of massive reserves, only about 20-30% ( @ 300 billion barrels) is deemed recoverable with current technology due to the oil’s natural, stubborn immobility.

In short, Ghawar’s high recovery rate and low extraction cost is due to its excellent permeability and natural drive mechanisms. These differences underscore Orinoco’s “stranded” resource status versus Ghawar’s prolific output. Accordingly, production processes for these fields diverge markedly due to their physical properties.

Ghawar benefits from natural reservoir pressure, allowing primary recovery through simple vertical wells where oil flows freely to the surface at low cost (under $5 per barrel in many cases). Production commenced in 1951, peaking at over 5 million barrels per day (mbpd) in the 1980s, sustained by water injection since the 1960s to maintain pressure. Current output is around 3.5-3.8 mbpd, managed for longevity.

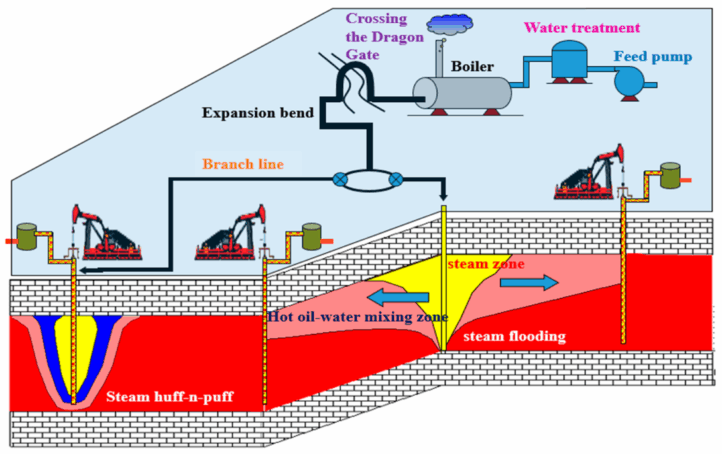

Zuata production, starting in earnest in the 1990s, required high-cost advanced enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques from the outset. Steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) or cyclic steam stimulation injects hot steam to heat the viscous oil, reducing viscosity for flow through horizontal wells. This energy-intensive process demands massive water and fuel inputs, with wells costing $10-20 million each versus Ghawar’s $1-5 million.

Due to this far more energy and capital intensive production process, the Orinoco fields demand a high level of equipment maintenance and replacement. The socialist govenrment’s failure to make these investments has caused total output to plummet to under 1 mbpd, far below its 3 mbpd potential.

Post-extraction processing highlights further contrasts. Ghawar’s light crude needs minimal treatment – basic separation of water and gas – at the wellhead before pipe-lining to refineries. Its natural pressure aids transport over long distances without dilution.

Zuata, however, must be heavily diluted with naphtha or lighter crudes (up to 30% by volume) to achieve pipeline-capable viscosity. That adds $10-15 per barrel in costs and requires dedicated upgraders to partially refine it into synthetic crude for export.

Finally, refining Ghawar’s medium-light sour crude is straightforward in standard facilities, yielding high proportions of valuable products like gasoline and diesel after desulfurization. Refining costs average $7-10 per barrel, with simple hydrocracking sufficient.

Zuata’s extra-heavy sour nature demands complex refineries with cokers and hydrotreaters to break down heavy residues, costing $12-15 per barrel or more. But that isn’t all. Crucially, the refined product yield from the Zuata heavy crude is far inferior to that of Saudi light crude for the simple reason that every first year petroleum geology student knows, but apparently no one on the Trump administration ever bothered to check out.

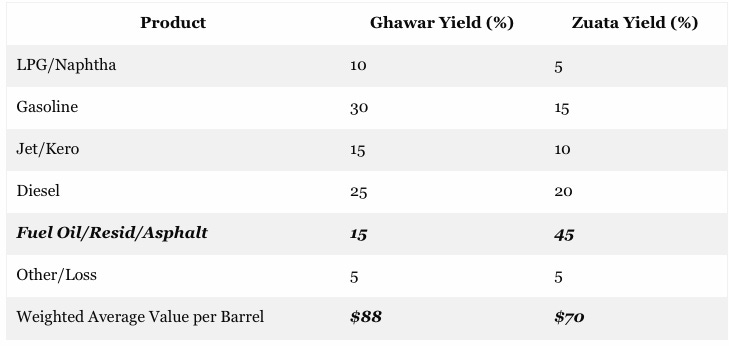

To wit, fully 45% of the refinery yield from Zuata heavy oil consists of low-value fuel oil, residual oils and asphalt, while the high-value light fraction yield (LPG/Naphtha, Gasoline, Jet/Kero) is just 30%. By contrast, the light fraction yield from the Ghawar crude is upwards of 55%, as shown in the table below.

In all, one barrel of crude at today’s wholesale market prices yields $88 of petroleum products from the Ghawar crude oil, but just $70 from the Orinoco Belt heavy crude represented by the Zuata grade.

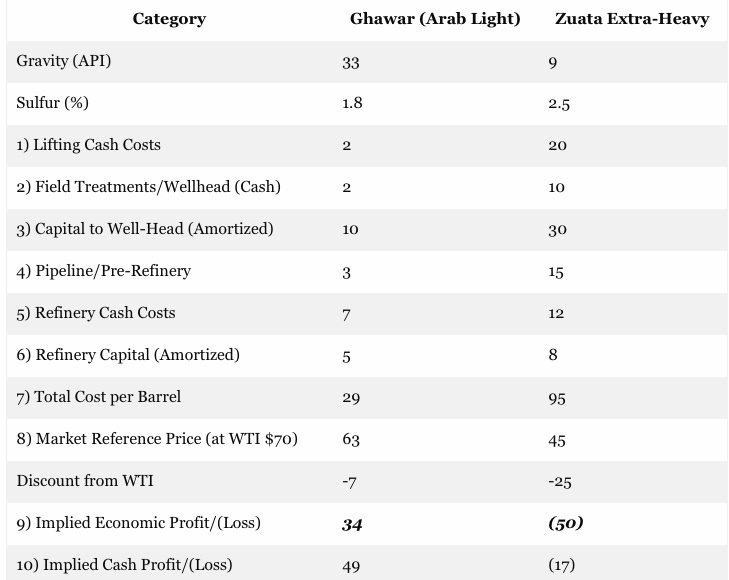

Product Yield Comparison: Ghawar (Arab Light) vs. Zuata Extra-Heavy Crude

Notes: Yields are rough estimates for typical refinery runs (simple for Ghawar, complex/upgraded for Zuata). Weighted values based on approximate January 2026 wholesale prices: LPG/Naphtha $70/bbl, Gasoline $90/bbl, Jet $85/bbl, Diesel $100/bbl, Fuel Oil/Resid/Asphalt $60/bbl (blended average; asphalt lower at ~$50/bbl). Calculations: Sum (yield % * price). Ghawar’s lighter slate yields higher-value products; Zuata’s heavies pull down the average.

Thus, at the long-term prevailing crude oil marker price of $70 per barrel for WTI, Mr. Market adds substantial cost premiums to convert Zuata heavy into saleable petroleum products. This includes the extra capital, steam, process chemicals, lifting equipment and diluents for pipeline transportation – and then another set of heavy duty cost penalties for extracting high value light petroleum products from the heavy hydrocarbon molecular chains contained in the Zuata heavy oil and various other grade extracted from the Orinoco Belt.

Even then, there is one negative aspect of the Venezuela heavy crudes that even the most advanced extraction and refining technologies imaginable down the road couldn’t overcome: To wit, Mother Nature pulled off a great robbery tens of millions of years ago, when the Orinoco Belt hydrocarbons were exposed to surface waters and other elements. The result was that a high percentage of the light fractions broke-down and evaporated into the mist, as it were. That’s why you get 45% low value bottoms when you refine a barrel of Zuata versus just 15% from Saudi Light.

So as shown below, the total vertically-integrated cost per barrel to get crude oil from its reseviors to the refinery gates is just $29 per barrel for Saudi Light versus $95 per barrel for Venezuelan Zuata grade. And then on top of that you have a extra $18 per barrel of discount from WTI owing to Mother Nature’s eons ago theft of the light fractions from the Orinoco Belt.

Needless to say, if it costs a whole lot more to produce and yields a goodly amount less revenue from refined products in the market place, the two commodities at issue here are similar only in that they are called “crude oil”. In the real world, they are actually miles apart when it comes to economics.

That is, the mighty Ghawar field is today generating vertically integrated economic profits of +$34 per barrel, while the Zuata heavy crude generates a -$50 per barrel loss; and even when you set aside capital cost recovery or amortization, which you can’t if you don’t wish to go bankrupt over the longer-term, the $49 per barrel cash profit from Ghawar turns into a $17 per barrel loss in the Orinoco.

Cost Comparison: Ghawar Light Crude (Arab Light) vs. Zuata Extra-Heavy Crude ($/bbl)

Footnotes:

- Gravity and Sulphur values use midpoint of standard range where applicable.

- 1: Lower for conventional fields like Ghawar; higher for heavy/unconventional like Zuata steam injection.

- 2: Minimal for light crudes; increases with viscosity/sourness (e.g., diluents for Zuata).

- 3: Low for mature fields (Ghawar); higher for heavy extraction (Zuata ~$40k-60k per flowing bbl).

- 4: Cheap pipelines for Ghawar; higher for remote/heavy (e.g., diluent costs $10-15/bbl for Zuata).

- 5: Light sweet minimal; sour/heavy adds $2-10/bbl for desulfurization/coking.

- 6: Simple refineries for sweets; complex units add $2-5/bbl amortized for heavies.

- 7: Full-cycle total cost (including amortized capex).

- 8: Typical realized price when WTI is $70/bbl (e.g., Arab Light small discount; heavies discounted $20-30/bbl). Notional averages; actuals fluctuate with markets/sanctions.

- Discount from WTI: Negative value indicates how much below $70/bbl each crude typically trades.

- 9: Economic profit/loss = Market Price – Total Cost (covers cash costs + amortized capex).

- 10: Cash profit/loss = Market Price – Cash Costs only (lines 1,2,4,5; excludes amortized capex in lines 3 & 6). All figures notional; vary with tech/markets.

So there will be no bonanza – even if the Trumpian cowboys succeed in stealing oil from the sovereign state of Venezuela. But even more pointedly, the argument that we need to start a war so that China doesn’t get the privilege of loosing its shirt in the Orinoco petroleum swamp is downright ludicrous.

Yet, the US ambassador to the United Nations on Monday said that enemies of his country cannot be allowed to control vast oil reserves, such as the ones in Venezuela under President Nicolas Maduro:

We’re not going to allow the Western Hemisphere to be used as a base of operation for our nation’s adversaries,” Waltz said. “You cannot continue to have the largest energy reserves in the world under the control of adversaries of the United States, under the control of illegitimate leaders, and not benefiting the people of Venezuela.

The truth is, this is the stupidest reason yet offered by the neocons for starting another Forever War. And yet the MAGA Hats stand with mouth wide open like the idiotic Walz waving the flag and praising the wanna be Macho Man who betrayed them.

David Stockman was a two-term Congressman from Michigan. He was also the Director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Ronald Reagan. After leaving the White House, Stockman had a 20-year career on Wall Street. He’s the author of three books, The Triumph of Politics: Why the Reagan Revolution Failed, The Great Deformation: The Corruption of Capitalism in America, TRUMPED! A Nation on the Brink of Ruin… And How to Bring It Back, and the recently released Great Money Bubble: Protect Yourself From The Coming Inflation Storm. He also is founder of David Stockman’s Contra Corner and David Stockman’s Bubble Finance Trader.

Regime change in Venezuela: Echoes of Iraq 2003

The forcible abduction of President Nicolas Maduro and Cilia Flores — not only Maduro’s wife but a former head of the National Assembly — along with the killing of at least 80 civilians and military personnel, including 32 Cuban guards of Maduro, clearly represents a serious violation of Venezuelan sovereignty and the United Nations Charter.

Trump’s assertive approach resembles the gunboat diplomacy of the 1850s, in which military powers seized resources from weaker nations. This confrontational approach reinforces the view that the US’s usual 21st-century foreign policy emphasises violence and dominance. The recent rise in violence and Maduro’s abduction are linked to a new National Security Strategy, issued by the White House in November 2025, that openly announces a “ Trump corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine.

The case for hemispheric dominance has roots in President James Monroe’s 1823 declaration, where he regarded Latin America as within the US sphere of influence and warned against foreign incursions, a stance known as the Monroe Doctrine. Theodore Roosevelt further expanded this concept in 1904 by introducing the “Roosevelt Corollary,” asserting that the US would act as an “international police power” to deter European interference and safeguard US interests in the Western Hemisphere.

Today, Trump's new National Security Strategy revisits the Monroe Doctrine corollary:

On December 2, 1823, the doctrine of American sovereignty was immortalized in prose when President James Monroe declared before the Nation a simple truth that has echoed throughout the ages: The United States will never waver in defense of our homeland, our interests, or the well-being of our citizens. Today, my Administration proudly reaffirms this promise under a new “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine: That the American people—not foreign nations nor globalist institutions — will always control their own destiny in our hemisphere (Trump, 2025)

The Trump administration made clear that Venezuela and its enormous oil reserves, the largest globally, are the main focus of these aggressive measures, rather than the unsupported claim that Maduro is engaged in illegal drug trade. Trump openly stated in media interviews and provocative social media posts that US military actions will only intensify “Until such time as they return to the United States of America all of the Oil, Land, and other Assets that they previously stole from us”. In support of these threats, the US intercepted oil tankers at sea in a manner resembling piracy and enforced a naval blockade — an act of war intended to deprive Venezuela of resources.

The recent assault on Venezuela is not the inaugural instance of the US undertaking actions against that nation. The pressure campaign commenced in the early 2000s when Hugo Chavez endeavoured to alter the terms of existing oil agreements. During the 1990s, nearly all prominent international oil corporations were present in Venezuela, investing in and exploiting Venezuelan oil. BP, CNPC, Conoco, Chevron, ENI, Exxon, Petrobras, Repsol, Shell, Statoil and Total, among others, had significant business interests.

In 2001, Hugo Chávez's government unilaterally enacted the Decreto con Fuerza de Ley Organica de Hidrocarburos (Hydrocarbons Law), which established state ownership over all oil and gas reserves and regulated upstream exploration and extraction via state-owned companies. It did, however, allow private firms — both domestic and foreign — to participate in downstream activities such as refining and marketing sales. This action angered US oil giants such as ExxonMobil and Chevron, which called on the George W Bush Jr administration to pressure Chávez to reverse the nationalisation of the industry.

This tension led to an April 2002 US-supported coup that temporarily removed Chávez from power and placed him in detention, before widespread protests forced his return. Between December 2002 and February 2003, the White House supported an executive lockout in the critical oil sector, backed by corrupt trade union officials aligned with Washington and the AFL-CIO. After three months, the lockout ended through an alliance of loyalist trade unionists, mass organisations, and oil-producing countries overseas.

In 2007, the Chávez government initiated another wave of nationalisations, undoing the decade-long privatisation and transfer of operations to US-based corporations. This step was taken after ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips declined to agree to new terms for continued heavy oil extraction in Venezuela’s Orinoco River basin, indicating their exit from one of the world’s largest oil regions. Four other oil companies — US-based Chevron Corp, BP PLC, France’s Total SA and Norway’s Statoil ASA — signed deals to accept minority shares in the oil projects under new terms set by Chavez’s government.

Following Chávez's death and Maduro's election in 2013, Venezuela’s economy contracted sharply amid a drop in global oil prices. As a result, the country experienced widespread migration and a sharp decline in living standards. Many factors have contributed to Venezuela’s crisis, including mismanagement of oil wealth, criminality, lawlessness and the black market. While all of these have undoubtedly played a part, the global decline in oil prices has been the primary cause of Venezuela's difficulties.

In 2014, after some hesitation and discussions in the early part of the year, Saudi Arabia launched an oil price war in tandem with the US. The US supported the policy to undermine the influence of oil-dependent Russia, something it apparently considered more important than supporting its own fracking sector. Access to cheap imported oil was also considered good news for US consumers and industry in general. Whether or not there was a clearly planned and agreed strategy, there seemed to be an unmistakable convergence of interests between the Saudi and US positions.

However, this strategy of keeping oil prices down did not necessarily destroy the Russian or Iranian economies. Instead, the hardest-hit oil-producing nations were in South America and Africa, where petro-states such as Libya, Angola and Nigeria suffered. The worst-affected country of all was Venezuela, the most disastrously oil-dependent state in the world. Oil accounts for 96% of exports and more than 40% of government revenues.

This situation was worsened by strict economic sanctions imposed during Barack Obama’s Democratic administration, which have since been further intensified. The escalation of sanctions by the US government has created further difficulties for Venezuela, with Maduro blaming the sanctions for an effort to overthrow his government.

US involvement in the country since has included coup plots, attempted assassinations and the landing of mercenaries on Venezuela’s shores. The first Trump administration sought to install its preferred president, Juan Guaidó, an unelected and largely unknown right-wing legislator, whose “interim government” failed to win popular backing and was only effective at stealing millions of dollars in US aid funding.

The latest National Security Strategy document set the stage for the recent aggression toward the Venezuelan regime:

After years of neglect, the United States will reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere, and to protect our homeland and our access to key geographies throughout the region. We will deny non-Hemispheric competitors the ability to position forces or other threatening capabilities, or to own or control strategically vital assets, in our Hemisphere. This “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine is a common-sense and potent restoration of American power and priorities, consistent with American security interests (National Security Strategy, 2025: 15).

The forcible abduction of President Nicolas Maduro and Cilia Flores — not only Maduro’s wife but a former head of the National Assembly — along with the killing of at least 80 civilians and military personnel, including 32 Cuban guards of Maduro, clearly represents a serious violation of Venezuelan sovereignty and the United Nations Charter.

Trump’s assertive approach resembles the gunboat diplomacy of the 1850s, in which military powers seized resources from weaker nations. This confrontational approach reinforces the view that the US’s usual 21st-century foreign policy emphasises violence and dominance. The recent rise in violence and Maduro’s abduction are linked to a new National Security Strategy, issued by the White House in November 2025, that openly announces a “ Trump corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine.

The case for hemispheric dominance has roots in President James Monroe’s 1823 declaration, where he regarded Latin America as within the US sphere of influence and warned against foreign incursions, a stance known as the Monroe Doctrine. Theodore Roosevelt further expanded this concept in 1904 by introducing the “Roosevelt Corollary,” asserting that the US would act as an “international police power” to deter European interference and safeguard US interests in the Western Hemisphere.

Today, Trump's new National Security Strategy revisits the Monroe Doctrine corollary:

On December 2, 1823, the doctrine of American sovereignty was immortalized in prose when President James Monroe declared before the Nation a simple truth that has echoed throughout the ages: The United States will never waver in defense of our homeland, our interests, or the well-being of our citizens. Today, my Administration proudly reaffirms this promise under a new “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine: That the American people—not foreign nations nor globalist institutions — will always control their own destiny in our hemisphere (Trump, 2025)

The Trump administration made clear that Venezuela and its enormous oil reserves, the largest globally, are the main focus of these aggressive measures, rather than the unsupported claim that Maduro is engaged in illegal drug trade. Trump openly stated in media interviews and provocative social media posts that US military actions will only intensify “Until such time as they return to the United States of America all of the Oil, Land, and other Assets that they previously stole from us”. In support of these threats, the US intercepted oil tankers at sea in a manner resembling piracy and enforced a naval blockade — an act of war intended to deprive Venezuela of resources.

The recent assault on Venezuela is not the inaugural instance of the US undertaking actions against that nation. The pressure campaign commenced in the early 2000s when Hugo Chavez endeavoured to alter the terms of existing oil agreements. During the 1990s, nearly all prominent international oil corporations were present in Venezuela, investing in and exploiting Venezuelan oil. BP, CNPC, Conoco, Chevron, ENI, Exxon, Petrobras, Repsol, Shell, Statoil and Total, among others, had significant business interests.

In 2001, Hugo Chávez's government unilaterally enacted the Decreto con Fuerza de Ley Organica de Hidrocarburos (Hydrocarbons Law), which established state ownership over all oil and gas reserves and regulated upstream exploration and extraction via state-owned companies. It did, however, allow private firms — both domestic and foreign — to participate in downstream activities such as refining and marketing sales. This action angered US oil giants such as ExxonMobil and Chevron, which called on the George W Bush Jr administration to pressure Chávez to reverse the nationalisation of the industry.

This tension led to an April 2002 US-supported coup that temporarily removed Chávez from power and placed him in detention, before widespread protests forced his return. Between December 2002 and February 2003, the White House supported an executive lockout in the critical oil sector, backed by corrupt trade union officials aligned with Washington and the AFL-CIO. After three months, the lockout ended through an alliance of loyalist trade unionists, mass organisations, and oil-producing countries overseas.

In 2007, the Chávez government initiated another wave of nationalisations, undoing the decade-long privatisation and transfer of operations to US-based corporations. This step was taken after ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips declined to agree to new terms for continued heavy oil extraction in Venezuela’s Orinoco River basin, indicating their exit from one of the world’s largest oil regions. Four other oil companies — US-based Chevron Corp, BP PLC, France’s Total SA and Norway’s Statoil ASA — signed deals to accept minority shares in the oil projects under new terms set by Chavez’s government.

Following Chávez's death and Maduro's election in 2013, Venezuela’s economy contracted sharply amid a drop in global oil prices. As a result, the country experienced widespread migration and a sharp decline in living standards. Many factors have contributed to Venezuela’s crisis, including mismanagement of oil wealth, criminality, lawlessness and the black market. While all of these have undoubtedly played a part, the global decline in oil prices has been the primary cause of Venezuela's difficulties.

In 2014, after some hesitation and discussions in the early part of the year, Saudi Arabia launched an oil price war in tandem with the US. The US supported the policy to undermine the influence of oil-dependent Russia, something it apparently considered more important than supporting its own fracking sector. Access to cheap imported oil was also considered good news for US consumers and industry in general. Whether or not there was a clearly planned and agreed strategy, there seemed to be an unmistakable convergence of interests between the Saudi and US positions.

However, this strategy of keeping oil prices down did not necessarily destroy the Russian or Iranian economies. Instead, the hardest-hit oil-producing nations were in South America and Africa, where petro-states such as Libya, Angola and Nigeria suffered. The worst-affected country of all was Venezuela, the most disastrously oil-dependent state in the world. Oil accounts for 96% of exports and more than 40% of government revenues.

This situation was worsened by strict economic sanctions imposed during Barack Obama’s Democratic administration, which have since been further intensified. The escalation of sanctions by the US government has created further difficulties for Venezuela, with Maduro blaming the sanctions for an effort to overthrow his government.

US involvement in the country since has included coup plots, attempted assassinations and the landing of mercenaries on Venezuela’s shores. The first Trump administration sought to install its preferred president, Juan Guaidó, an unelected and largely unknown right-wing legislator, whose “interim government” failed to win popular backing and was only effective at stealing millions of dollars in US aid funding.

The latest National Security Strategy document set the stage for the recent aggression toward the Venezuelan regime:

After years of neglect, the United States will reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere, and to protect our homeland and our access to key geographies throughout the region. We will deny non-Hemispheric competitors the ability to position forces or other threatening capabilities, or to own or control strategically vital assets, in our Hemisphere. This “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine is a common-sense and potent restoration of American power and priorities, consistent with American security interests (National Security Strategy, 2025: 15).

Venezuelan oil

After capturing Maduro and Flores, Trump stated at a media conference from his Mar-a-Lago estate in Palm Beach, Florida: “We are going to run the country until such time as we can do a safe, proper and judicious transition.” He added the goal of the intervention in Venezuela was to take control of the country and its oil resources. “We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars,” Trump declared. Trump warned of escalating military onslaught if there was any resistance: “We are ready to stage a second and much larger attack if we need to do so.”

Venezuela is known not only for its vast oil reserves but its wealth of other vital resources. The country holds notable gold reserves, primarily in the southeast (the Guiana Highlands). Diamond deposits occur in the Guiana region, although they are less extensive than those of gold and bauxite. Venezuela also has documented deposits of copper, nickel and manganese, along with smaller amounts of coltan and cassiterite associated with emerging mining areas. Surveys suggest that significant quantities of uranium and thorium may also be present.

Major US financial firms, including hedge funds and asset managers such as Goldman Sachs, BlackRock and T. Rowe Price, are positioning themselves to benefit from Venezuela’s abundant oil and mineral resources. They are targeting distressed assets of the state oil company PDVSA, as well as opportunities in gold, diamonds, and rare-earth minerals. The Wall Street Journal reported that top hedge funds and asset managers are planning to send a delegation of about 20 business leaders to Caracas in March. They will evaluate what one investor described as $500–$750 billion in “investment opportunities,” focusing on the energy sector and infrastructure over the next five years.

Venezuela holds approximately 300–303 billion barrels of proven reserves, making up about 17% of the world's total, and slightly surpassing Saudi Arabia. Nevertheless, a key point is that roughly 75% of this volume consists of extra-heavy crude from the Orinoco Belt in eastern Venezuela. These oils are similar to bitumen, with API gravity typically between 8–14°, making them highly viscous under reservoir conditions and rich in sulphur and metals.

The claim of “largest reserves” mainly refers to the largest booked quantities of very heavy and extra-heavy oil, which are especially difficult to extract. Although Venezuela has the largest total proven oil reserves, most of them consist of extra-heavy oil, which is thick and highly viscous, making it more costly to refine than light conventional oil.

Therefore, expecting quick gains from controlling these resources is unrealistic. It requires substantial, long-term investment, and even then, extracting heavy oil is only economical when global oil prices are very high. Extracting oil from the ground would necessitate staggering levels of investment to develop the required technology, infrastructure and expertise. Restoring Venezuela’s oil output to its late-1990s peak of 3 million barrels daily would need an additional $20 billion in capital investment beyond what the top five US oil companies spent worldwide in 2024, according to consultancy Rystad Energy.

Also, even if the Venezuelan oil sector is developed with significant investment from oil giants or with US state funds, this may not benefit the US economy. The shale oil sector is extremely significant for the US, transforming the country into the world’s leading oil producer, drastically reducing reliance on imports, boosting exports, reshaping global markets and providing major economic benefits. This “Shale Revolution”, powered by horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, has fundamentally altered US energy security and the US’s role in the global energy landscape.

Currently, the US is the world’s largest producer of shale oil, but its production is highly dependent on continuous drilling to sustain growth. For thousands of public and private shale operators, a revitalised Venezuelan oil industry would worsen the market glut. Shale drilling is costly, and companies need a barrel of West Texas Intermediate, the US benchmark, to trade above $60 to turn a profit. Its price fell below $56 a barrel soon after Trump’s operation against Venezuela.

After capturing Maduro and Flores, Trump stated at a media conference from his Mar-a-Lago estate in Palm Beach, Florida: “We are going to run the country until such time as we can do a safe, proper and judicious transition.” He added the goal of the intervention in Venezuela was to take control of the country and its oil resources. “We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies, the biggest anywhere in the world, go in, spend billions of dollars,” Trump declared. Trump warned of escalating military onslaught if there was any resistance: “We are ready to stage a second and much larger attack if we need to do so.”

Venezuela is known not only for its vast oil reserves but its wealth of other vital resources. The country holds notable gold reserves, primarily in the southeast (the Guiana Highlands). Diamond deposits occur in the Guiana region, although they are less extensive than those of gold and bauxite. Venezuela also has documented deposits of copper, nickel and manganese, along with smaller amounts of coltan and cassiterite associated with emerging mining areas. Surveys suggest that significant quantities of uranium and thorium may also be present.

Major US financial firms, including hedge funds and asset managers such as Goldman Sachs, BlackRock and T. Rowe Price, are positioning themselves to benefit from Venezuela’s abundant oil and mineral resources. They are targeting distressed assets of the state oil company PDVSA, as well as opportunities in gold, diamonds, and rare-earth minerals. The Wall Street Journal reported that top hedge funds and asset managers are planning to send a delegation of about 20 business leaders to Caracas in March. They will evaluate what one investor described as $500–$750 billion in “investment opportunities,” focusing on the energy sector and infrastructure over the next five years.

Venezuela holds approximately 300–303 billion barrels of proven reserves, making up about 17% of the world's total, and slightly surpassing Saudi Arabia. Nevertheless, a key point is that roughly 75% of this volume consists of extra-heavy crude from the Orinoco Belt in eastern Venezuela. These oils are similar to bitumen, with API gravity typically between 8–14°, making them highly viscous under reservoir conditions and rich in sulphur and metals.

The claim of “largest reserves” mainly refers to the largest booked quantities of very heavy and extra-heavy oil, which are especially difficult to extract. Although Venezuela has the largest total proven oil reserves, most of them consist of extra-heavy oil, which is thick and highly viscous, making it more costly to refine than light conventional oil.

Therefore, expecting quick gains from controlling these resources is unrealistic. It requires substantial, long-term investment, and even then, extracting heavy oil is only economical when global oil prices are very high. Extracting oil from the ground would necessitate staggering levels of investment to develop the required technology, infrastructure and expertise. Restoring Venezuela’s oil output to its late-1990s peak of 3 million barrels daily would need an additional $20 billion in capital investment beyond what the top five US oil companies spent worldwide in 2024, according to consultancy Rystad Energy.

Also, even if the Venezuelan oil sector is developed with significant investment from oil giants or with US state funds, this may not benefit the US economy. The shale oil sector is extremely significant for the US, transforming the country into the world’s leading oil producer, drastically reducing reliance on imports, boosting exports, reshaping global markets and providing major economic benefits. This “Shale Revolution”, powered by horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, has fundamentally altered US energy security and the US’s role in the global energy landscape.

Currently, the US is the world’s largest producer of shale oil, but its production is highly dependent on continuous drilling to sustain growth. For thousands of public and private shale operators, a revitalised Venezuelan oil industry would worsen the market glut. Shale drilling is costly, and companies need a barrel of West Texas Intermediate, the US benchmark, to trade above $60 to turn a profit. Its price fell below $56 a barrel soon after Trump’s operation against Venezuela.

Geopolitical motives

There is a clear geopolitical motivation behind this aggression against Venezuela, rather than a purely economic one. Gillian Tett of the Financial Times described Trump’s policies as “an ugly form of ‘retro imperialism’ based on a sphere of influence mantra – and naked plunder”. In the traditional sense of spheres of influence, Trump’s actions can be perceived as a strategic endeavour to prevent other powers from gaining access to Venezuela’s abundant resources.

In an interview on NBC, Secretary of State Marco Rubio was asked why the US needs to control Venezuela’s oil industry. He responded, “We don’t need Venezuela’s oil. We have plenty of oil in the United States. What we’re not going to allow is for the oil industry in Venezuela to be controlled by adversaries of the United States”, naming Russia, China and Iran. “This is the Western Hemisphere. This is where we live. And we’re not going to allow the Western Hemisphere to be a base of operations for adversaries, competitors, and rivals of the United States, simple as that.”

In this context, the conflict with Venezuela serves a key geopolitical goal. The invasion of Venezuela and the detention of its president are, as Trump stated, intended as a “warning” to “anyone who would threaten American interests”. Referring to his new National Security Strategy, Trump declared that “American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never be questioned again.” Referring to the notorious “blood and iron” speech by the nineteenth-century Prussian military leader Bismarck, Trump hailed the assault as a reaffirmation of the “iron laws that have always determined global power.”

The immediate targets of this policy are governments in Latin America that may act against US global interests. Speaking of Colombian President Gustavo Petro, Trump warned in the language of a street thug: “He has to watch his ass.” Secretary of War Pete Hegseth added, “America can project our will anywhere, anytime,” drawing a direct comparison between Venezuela and the US bombing of Iranian nuclear facilities last year: “Maduro had his chance,” he sneered, “just like Iran had their chance — until they didn’t”.

However, the threats extend beyond Latin America. Trump is warning both allies and enemies across the hemisphere. Besides Venezuela and Iran, the US conducted bombings in five other countries last year: Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia and Nigeria in December. Trump has threatened war with Mexico, suggested annexing Greenland and Canada, and insisted that the Panama Canal remains “non-negotiable” for US control.

The message to China is explicit and assertive. Just hours before the attack, Maduro met with a high-level Chinese delegation, led by Beijing’s Special Representative for Latin American and Caribbean Affairs Qiu Xiaoqi, to emphasise energy cooperation. The US raid, coordinated with this meeting, was a provocative move intended to disrupt the expanding relationship between China and Latin America. China has already surpassed the US as South America’s main trading partner and is projected to become the leading partner across Latin America and the Caribbean by 2035.

There is a clear geopolitical motivation behind this aggression against Venezuela, rather than a purely economic one. Gillian Tett of the Financial Times described Trump’s policies as “an ugly form of ‘retro imperialism’ based on a sphere of influence mantra – and naked plunder”. In the traditional sense of spheres of influence, Trump’s actions can be perceived as a strategic endeavour to prevent other powers from gaining access to Venezuela’s abundant resources.

In an interview on NBC, Secretary of State Marco Rubio was asked why the US needs to control Venezuela’s oil industry. He responded, “We don’t need Venezuela’s oil. We have plenty of oil in the United States. What we’re not going to allow is for the oil industry in Venezuela to be controlled by adversaries of the United States”, naming Russia, China and Iran. “This is the Western Hemisphere. This is where we live. And we’re not going to allow the Western Hemisphere to be a base of operations for adversaries, competitors, and rivals of the United States, simple as that.”

In this context, the conflict with Venezuela serves a key geopolitical goal. The invasion of Venezuela and the detention of its president are, as Trump stated, intended as a “warning” to “anyone who would threaten American interests”. Referring to his new National Security Strategy, Trump declared that “American dominance in the Western Hemisphere will never be questioned again.” Referring to the notorious “blood and iron” speech by the nineteenth-century Prussian military leader Bismarck, Trump hailed the assault as a reaffirmation of the “iron laws that have always determined global power.”

The immediate targets of this policy are governments in Latin America that may act against US global interests. Speaking of Colombian President Gustavo Petro, Trump warned in the language of a street thug: “He has to watch his ass.” Secretary of War Pete Hegseth added, “America can project our will anywhere, anytime,” drawing a direct comparison between Venezuela and the US bombing of Iranian nuclear facilities last year: “Maduro had his chance,” he sneered, “just like Iran had their chance — until they didn’t”.

However, the threats extend beyond Latin America. Trump is warning both allies and enemies across the hemisphere. Besides Venezuela and Iran, the US conducted bombings in five other countries last year: Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia and Nigeria in December. Trump has threatened war with Mexico, suggested annexing Greenland and Canada, and insisted that the Panama Canal remains “non-negotiable” for US control.

The message to China is explicit and assertive. Just hours before the attack, Maduro met with a high-level Chinese delegation, led by Beijing’s Special Representative for Latin American and Caribbean Affairs Qiu Xiaoqi, to emphasise energy cooperation. The US raid, coordinated with this meeting, was a provocative move intended to disrupt the expanding relationship between China and Latin America. China has already surpassed the US as South America’s main trading partner and is projected to become the leading partner across Latin America and the Caribbean by 2035.

Iraq 2003 and Venezuela 2026

The Trump administration’s actions are not only criminal but demonstrate a dangerous level of recklessness. Trump, a sharp critic of the US invasion of Iraq, will now have to heed the words of one of the US architects of the Iraq War, Secretary of State Colin Powell: “If you break it, you own it.”

Mary Ellen O’Connell, a professor at Notre Dame Law School, likened Trump’s actions to the 2003 Iraq invasion. That invasion caused severe economic collapse, rising unemployment, increased divisions within the country, more violent resistance, civil strife, and ultimately empowered certain ISIS factions. When Obama announced the official end of the Iraq war and began the troop withdrawal in 2011, Iraq was left deeply traumatised and with a collapsing economy.

The conflict lasted eight years, resulting in more than 200,000 Iraqi civilian deaths and the loss of 4492 American service members. More than 32,000 service members were injured. The war’s total cost reached about $6 trillion, it destabilised the region, and Iraq was left with another authoritarian and unstable regime. The 2003 invasion was a significant and costly error. Even some prominent advocates of the war have since labelled it “a major mistake,” a catastrophe, or the “ single worst decision ever made.”

Similar to what Trump and his administration have repeatedly announced — namely that they now care about Venezuela and promise freedom and growth for the country — just three weeks before the Iraq War began, then-president Bush made similar promises about Iraq. He addressed the annual dinner of the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), emphasising the need to establish a “free Iraq.” By “protect[ing] Iraq’s natural resources from sabotage” and ousting the Saddam Hussein dictatorship, Bush hoped Iraqis could “fully share in the progress of our times”.

In the period leading up to the 2003 invasion, Iraq was often characterised in various media and political discourse as a nation on the brink of collapse, grappling with profound social and economic decay. Almost the same language can be found in the mainstream media in the West about Venezuela under Maduro.

The ongoing actions against Venezuela are even more reckless than Bush’s campaign in Iraq, appearing as a disaster waiting to happen. On January 10, Trump announced plans to impose a dictatorship in Venezuela, saying the country would be run by figures such as Rubio, Hegseth and other Trump officials. This ignores the reality that Venezuela, with its 30 million inhabitants and over 350,000 square miles, cannot be governed by Washington insiders. Such an occupation would demand hundreds of thousands of US troops and a challenging urban warfare campaign to deal with widespread resistance.

Trump underscored this by stating he is not afraid of having “ boots on the ground if we have to have [them].” It should be noted that the 2003 Iraq invasion involved more than 100,000 coalition troops, with a further 125,000 from the US. Over 340,000 US personnel were deployed in the region to support the campaign in Iraq.

Iraq, which has a smaller population than Venezuela, had already suffered ten years of sanctions. Still, it proved extremely difficult and costly for the US army to establish a stable system of control in the country, and eventually had to withdraw without achieving anything significant. Even in Washington, now many describe the 2003 intervention and following occupation of Iraq as “the biggest U.S. foreign policy blunder since the war in Vietnam”.

The invasion of Iraq was planned under the concept of rapid dominance and coordinated by a High-Value Target (HVT) Cell in the Pentagon. While attempting to hit Hussein through HVT, due to the kill chain time (the time between getting the intelligence and the missile impacting) being too long, many civilians were hit instead.

It was thought that drones would shrink the kill chain to zero by waiting for the target to appear and then launching a missile, without the time to assess collateral damage. During and following the invasion, precision strikes unsuccessfully targeted purported lairs of various Iraqi Commanders, as well as Hussein. Not so lucky, according to former Defense Intelligence Agency analyst Marc Garlasco, were the “couple of hundred civilians, at least” who were killed in the strikes.

By invading Iraq, the second-largest crude oil producer in OPEC, the US was expecting to gain physical and strategic control over energy supplies in the Middle East. Yet the Iraq created after the 2003 invasion, in which over 7500 civilians were killed in six weeks, the “new, democratic Iraq,” from the start showed signs of weakness in terms of power and societal cohesion.

Already poor, Iraq after the invasion and by 2009 remained weak and vulnerable in all its contexts: the political, the social and the economic, being exploited, lacking internal support and any capacity to cope with the total breakdown of security. Its citizens suffered the daily attacks of neighbouring states, terrorist groups, insurgents, and the occupying forces.

Even after the occupation officially ended in 2011, the damage done to Iraq went beyond the personal safety of its citizens: it extended to the identity and values of its communities, their sense of belonging and of being protected, their sense of living in a “homeland.” The result is domestic unrest and threats to national and regional security, especially when the state is weak and therefore vulnerable.

The military occupation required to control Venezuela could also lead to a bloody and extended conflict in the country, throughout Latin America and potentially beyond. As in Iraq, it could be very costly for the occupying power and lead to human insecurity at high levels: personal, economic, political, food, health and energy.

The Trump administration’s actions are not only criminal but demonstrate a dangerous level of recklessness. Trump, a sharp critic of the US invasion of Iraq, will now have to heed the words of one of the US architects of the Iraq War, Secretary of State Colin Powell: “If you break it, you own it.”