THE EPSTEIN CLASS

When British author David Icke wrote his seminal work, The Biggest Secret: The Book That Will Change the World, published in 1999, he was not speaking metaphorically. When he detailed the “reptilian genetic streams” of “elite” families—human-reptile hybrids allegedly engineering global events—he meant it literally. To Icke, the world is not run by mere men, but by an interdimensional species operating just outside the visible light spectrum.

While many scoff at this as the ultimate apex of human gullibility, millions have found a dark comfort in Icke’s “wisdom”. According to a landmark 2013 poll by Public Policy Polling (PPP), roughly 4 percent of American adults—between 12 and 13 million people—believed that shape-shifting lizard people control our world.

Conspiracy theories in the United States occupy a wide spectrum of beliefs. While the ‘Reptilian’ theory sits at the fringe, other theories command mainstream traction. According to that same study, 51 percent of Americans believed a larger conspiracy was behind the JFK assassination, 37 percent viewed global warming as a hoax, and 29 percent were certain that aliens exist.

Recently, these fringe ideas have drifted toward official discourse. In 2021, former President Barack Obama told NBC News James Corden that “there’s footage and records of objects in the skies, that we don’t know exactly what they are,” and later stated in 2026 that aliens are “real”. This was followed by a statement by US President Donald Trump, who declared that he will begin “the process of identifying and releasing Government files related to alien and extraterrestrial life”. This rhetorical tug-of-war has effectively moved the ‘extraterrestrial’ conversation from the realm of the tabloid to the halls of mainstream politics.

However, the most significant shift in public skepticism didn’t come from space, but from a private island. The ‘Epstein Files’—the documented evidence of a shadow network operated by Jeffrey Epstein—unveiled a web of influential statesmen, corporate titans, and intelligence assets. To those who believed in a ‘New World Order’ conspiracy back in 2013 (then 28 percent of the population), the millions of documents released through the US Department of Justice proceedings provided a grim validation. They pointed to a shadow government operating entirely outside the confines of democratic accountability.

The specific crimes of Jeffrey Epstein are now a matter of public record, thanks to the tireless efforts of survivors and investigative journalists. But for political science, the Epstein saga represents a ‘Galileo moment.’ It is the realization that our institutions are not the center of the political universe, but are often satellites orbiting private elite interests.

Historically, we have been taught to view the world through a few primary lenses: Realism, which focuses on state-on-state power and national security; Liberalism, which champions international institutions and the ‘rule of law’; and Dependency Theory, which highlights the economic exploitation of the ‘Periphery’, the developing nations, by the ‘Core’, the wealthy nations.

Under these frameworks, we analyzed the Nixon era through Realpolitik, the Clinton years through Liberal Internationalism, and the Bush years through Neoconservatism. But the Epstein network challenges all of them. This is no longer about Core vs. Periphery or ‘containment’ vs. ‘preemptive war’.

Traditional theory assumes leaders act on behalf of their citizens. The Epstein files suggest a different reality: a secretive social contract bound by mutual vulnerability and blackmail. In this system, shared secrets are a more stable currency than gold or votes. We are witnessing the rise of the Transnational Elite Theory. This framework suggests the true ‘state’ is a borderless network of high-net-worth individuals who share more in common with each other than with the citizens of their own countries.

These ‘sovereign individuals’ fly above national laws in private jets, moving assets through jurisdictional gaps that the average citizen cannot see. They don’t just influence the law; they exist in the gray zones in between. For decades, victims spoke out, but mainstream institutions marginalized them. In the chessboard of power, they were too insignificant to matter. The failure of oversight bodies wasn’t a glitch—it was evidence of a system repurposed to function as a support system for the elite.

The implications for our future understanding of power are profound. If the primary driver of high-level policy is no longer the ballot box or national interest, but rather the preservation of opaque, transnational networks, then our current democratic models are essentially obsolete. We are forced to admit that the political theater we witness daily—the debates, the elections, and the legislative battles—may merely be a superficial layer designed to distract from the deeper, darker mechanics of the global hierarchy.

Furthermore, this paradigm shift suggests that the ‘marginalized’ of the world are not just those in impoverished nations, but anyone excluded from this high-networked social contract. The divide is no longer strictly between the Core and the Periphery of nation-states, but between the networked elite and the disconnected public.

Now that the public sees the liberal world order as a system that applies rules only to the un-networked, it has lost its moral authority. While the old theories remain useful for understanding the history of politics, they cannot explain its current state. The elites are a powerful network capable of acting against their own governments’ national interests to achieve political power, private leverage and wealth.

Perhaps the literal lizard people have yet to be revealed in the sense that Icke tirelessly promotes. But as the Epstein saga proves, a predatory, cold-blooded, and non-accountable elite is no longer a theory—it is a documented reality

Epstein and the Politics of Distraction

February 27, 2026

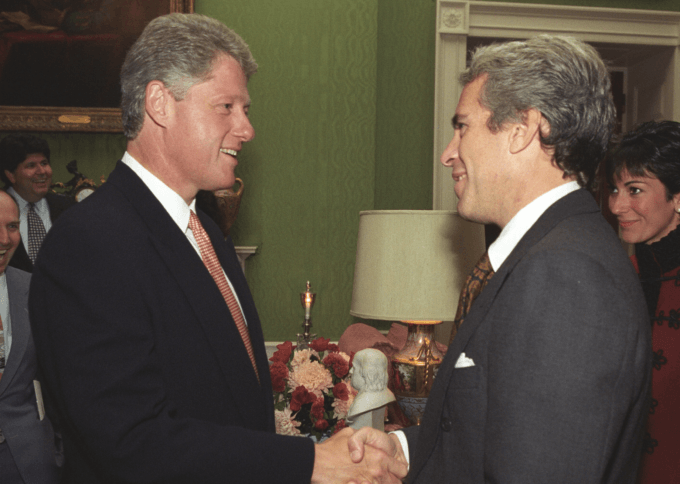

Epstein shaking hands with President Bill Clinton at the White House, September 1993 (with Ghislaine Maxwell in the background on the right).

After the beginning of Trump’s second term, the connections between capitalism, white supremacy and imperial domination became increasingly clear. These have been highlighted through ICE raids as modern-day slave patrols, global criminal operations such as the kidnapping of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores, and United States assistance to Israel’s genocide in Gaza as a bipartisan US and transnational corporate experiment.

The growing understanding that people in the Global South, along with Black, Indigenous and other People of Colour (BIPOC) within the imperial core, face a common enemy has galvanised an anti-colonial, revolutionary movement committed to radical transformation.

And then the release of the Epstein files flooded public discourse.

Epstein and the media

Jeffrey Epstein was a financier convicted of sex crimes involving minors. After renewed federal charges in 2019, he died in jail (officially ruled a suicide). The case triggered public outrage about ruling class impunity, media focus on unsavoury associations between the political and corporate class and a plethora of conspiratorial narratives about cover-ups.

The Epstein case became far more than a criminal proceeding; it reflects a symbolic exposure of ruling class impunity and concentrated power and a spectacle of corruption within an empire in deep crisis and decline.

The Epstein case exposed ruling class criminality while simultaneously displacing structural accountability.

Importantly, “spectacle” does not mean “fake”; it means the organisation of politics through symbolic drama that displaces structural political analysis. With spectacle, social contradictions (inequality, social crises and instability) are dramatised rather than structurally challenged.

The enduring media and public fixation on the Epstein files, particularly as their release proceeds with little accountability and continued narratives that discredit and isolate survivors, serves less as accountability and more as a political diversion from systemic injustices: Racism, capitalism, the growth of the police state and ongoing international impunity.

More troubling still, it marks another step in the erosion of democracy and the consolidation of expansionist, war-driven fascism.

Fascist spectacle

In work by Walter Benjamin, Hannah Arendt, Guy Debord, Umberto Eco and others, fascist spectacle involves anti-intellectual and emotionally driven mass mobilisation around simple moral binaries (pure people v the corrupt ruling class), where action is revered while thought is reviled; the replacement of institutional process with symbolic imagery and drama; and mythic narratives of national decay and rebirth. Political theorist Roger Griffin calls this rebirth “palingenic ultranationalism”, that is, destruction as a precondition for rebirth.

Conspiracy theories are the narrative engine of spectacle. They transform systemic crisis and social instability into simple, emotionally gripping stories of social taboo-breaking, centred on hidden and untouchable enemies, laying the groundwork through which authoritarian solutions are marketed as necessary and even redemptive.

When structural violence becomes visible, but accountability remains absent, public anger often seeks explanation through personalised and conspiratorial narratives rather than systemic analysis.

Theories like these, whether wholly true, partially true or false, are not new; fascist movements have historically mobilised around the idea that the nation is being secretly corrupted by a degenerate ruling class, with a radical cleansing necessary to return to a righteous path.

The criminality of Epstein and the powerful figures who orbited him and participated in his abuses have come to symbolise a degenerate ruling class with identifiable names and faces, targets who could be exposed and jailed, thereby clearing the narrative space for a heroic white knight to ride in with promises of salvation.

As Hannah Arendt warned, conspiracy thinking thrives when trust in institutions collapses. The Epstein scandal intensified the sense of a ruling class operating above the law and of a justice system which protects its own, conditions ideal for authoritarian movements to exploit by insisting the system is irredeemably rigged and that only a strong leader can tear it down.

As such, the spectacle of the Epstein scandal can absorb and manipulate public outrage, redirecting it away from necessary structural accountability in the form of decolonisation and redistribution of wealth, ultimately reinforcing the very systems it appears to challenge.

In doing so, it promotes the aesthetics of politics – the spectacle – rather than grounded critiques of capitalism and imperial power. Further, it serves to distract from failures ultimately promoting oppression and war. According to Federico Caprotti, various forms of fascist spectacle produce a “collage” which both expresses and obscures the syncretic ideology of the regime.

The grand spectacle: War

When politics becomes theatre rather than collective progress dependent on accountability, transformation or reform, crisis becomes emotional drama, drama demands release (internal resolution) or escalation and escalation inevitably finds its expression in externalised war, in which the nation performs a grand spectacle of unity and sacrifice on the largest possible stage.

War acts as a stabilising force when internal contradictions cannot be resolved through collective mobilisation. With its uniforms and marches, war channels discontent by uniting a fragmented, outraged population against an externalised enemy, transforming righteous anger at the violence, oppression and greed of a ruling class into manufactured unity, heroism and meaning through violence against “the other”.

These dynamics, outlined by Benjamin decades ago, feel alarmingly familiar in the present moment, including in the spectacle surrounding the Epstein scandal.

In this context, external conflict functions not only as policy but as emotional consolidation, redirecting internal disillusionment towards collective national purpose.

Fascist forces deploy such spectacles to distract and mobilise, and are doing so presently; accelerating the dismantling of what remains of US democracy and the post-war international order, to be replaced by a system ruled by force and naked self-interest.

Spectacle politics does not require loyalty to specific leaders but to the emotional narrative they embody, rendering individual figures ultimately expendable.

In this logic, even Trump could be discarded, sacrificed to clear the way for a “purer” white male strongman (Vance? Pence? Carlson?) who promises to cleanse the ruling class and by extension its foreign so-called “handlers” (enemies like Russia, China and Iran or even allies like Israel and Europe, the latter already being threatened by Trump), of its unsavoury elements, particularly if Trump’s baggage with Epstein proves politically irredeemable.

By contrast, liberation and reconciliation and an end to capitalist oppression, with its accompanying genocidal violence and planetary destruction, require a steadfast structural framework aligned with broader leftist, antiracist and anti-colonial principles. Such a framework prioritises systemic transformation over spectacle. Within this view, the Epstein scandal is not treated as the disease itself, but as a symptom of capitalism’s inherent corruption.

This piece first appeared on Al Jazeera.

In my book La société de provocation: essai sur l'obscénité des riches (The Society of Provocation: An Essay on the Obscenity of the Rich), I argue that this social order is anchored in a long-lasting alliance between economic and political elites, whose interests converge around the preservation of their privileges.

This alliance manifests in an economy of excess and overabundance — the so-called “wealthporn” or “pornopulence” — created for the ostentatious enjoyment of a small, protected elite. The Epstein case is only the tip of the iceberg. It reveals a global system that treats bodies, land and resources as things to exploit and discard for profit.

The Epstein revelations also compel us to examine this socially organized and institutionally protected class. Its power goes far beyond individual behaviour and rests on three inter-related social mechanisms: co-optation, insularization and neutralization.

Our mission is to share knowledge and inform decisions.About us

Co-optation: The male-only network

Co-optation describes an organized system of male networks at the top of power structures. This is a boys’ club as described by Québec professor and writer Martine Delvaux: a closed world governed by unwritten rules of loyalty, discretion and mutual protection.

The Epstein files show that this club encompasses individuals from diverse positions — political leaders, heirs, royalty, traders, tech entrepreneurs, renowned scientists and media personalities.

The list of names — among the richest and most powerful people on the planet— speaks to the reach of this network. But the club’s power derives less from wealth alone than from the convertibility of status into social capital.

Even less wealthy members are “richly connected” — they leverage their contacts, expertise and privileged access to decision-making circles. Their networks constitute highly convertible transnational social capital, to be deployed strategically: by sharing sensitive information, facilitating tax optimization or avoidance, gaining access to influential professionals (doctors, lawyers, judges), and participating in selective social spaces (private clubs, exclusive events, yachts, gated estates).

Within this system, women are treated as objects for transaction, distinction and pleasure. Co-optation therefore functions as both a political and sexual socialization of privilege.

Insularization of the wealthy

This relational system is reinforced by a process of elite insularization, in which the wealthiest gradually withdraw from the broader world so they can live by their own rules. Extreme concentration of wealth does more than deepen inequality; it allows the privileged to retreat into “zones of secession” — spaces removed from common rules and ordinary societal constraints.

The Epstein files reveal a mobile, transnational over-class, entrenched in exceptional enclaves where social, fiscal and political obligations are minimal: private islands, gated neighborhoods, offshore tax regimes, private cities and multiple residences.

Little St. James, now called “Epstein Island”, exemplifies this logic. This 75-acre private island in the U.S. Virgin Islands featured a helicopter landing pad and multiple hidden villas. According to testimony from numerous witnesses, it was also where Epstein allegedly delivered victims to some of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful men for sexual exploitation.

The pornopulent class does not only retreat into privatized spaces; it also seizes shared, historically public spaces, turning them into showcases of power, as seen in Jeff Bezos’s ostentatious wedding in Venice.

But the insularization of the rich isn’t just spatial or fiscal. It also entails a social and political withdrawal of elites from democratic life. Support from several figures linked to the Epstein files from authoritarian, libertarian and reactionary movements — such as Donald Trump, Elon Musk and Peter Thiel — fits into this pattern, as recently highlighted by Oxfam.

Read more: Donald Trump’s penchant for bullshit explains MAGA anger about the Epstein files

Neutralization of dissent

Finally, the Epstein case shows how complaints and dissent are neutralized, reinforcing class power. Despite repeated allegations and investigations, institutions meant to protect victims were circumvented, weakened or instrumentalized, while only a few people were punished. This reveals a familiar asymmetry: the more unequal a society, the more “justice” functions as protection for elites.

Neutralization relies first on unequal access to institutional resources. Specialized law firms, influence networks, PR firms and reputation industries favour confidential settlements, delay proceedings and exhaust victims.

It also relies on the close intertwining of political and media power. In the U.S., figures like Musk, Bezos, Larry Ellison and Mark Zuckerberg control media that’s increasingly aligned with Trump’s agenda in exchange for economic and regulatory benefits. By financing, acquiring or influencing media and digital platforms, the ruling elite narrows public debate and criticism.

Together, co-optation, insularization, and neutralization enable a class power that extends far beyond a single manipulative individual. They sustain a regime of predatory accumulation, in which economic and sexual violence reinforce each other for the benefit of a minority that enjoys, transgresses and flaunts with complete impunity.

Meanwhile, victims are silenced, contained by a dense network of legal, media and political protections for the elite even when some speak publicly, like the late Virginia Giuffre, without truly being heard. The Epstein case exposes a dangerous class whose power threatens not only women but the very foundations of democratic life.

Author

This article was originally published in French

The Epstein Affair, Again: “What about the Victims?”

Press outside Wood Farm, Sandringham Estate, Norfolk. Feb. 20, 2026. Photo: The author.

Sandringham

A day after the arrest of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor, formerly Prince Andrew, brother of King Charles and eighth in line of succession to the British throne, I visited Sandringham. That’s the estate in Norfolk, England, to which Andrew returned after 11 hours in custody at Aylsham police station, some 35 miles distant.

I arrived to see a scrum of about two dozen photographers and a few reporters, standing around, chatting, talking on the phone, fiddling with their gear, trying to stay dry. Three coppers stood together, about 30 feet away, beneath a broad cypress tree, in front of a flint wall surrounding the churchyard of the 14th C. Church of St. Mary Magdlelen.

“Quite the scene,” I said to the police, needlessly.

“Yes, sir,” said one, with finality. He had a Polish accent and pony-tail not quite tucked beneath his cap.

Undeterred, I continued: “I don’t suppose you generally see so many people here, far from the main gate of Sandringham Estate.”

“No, sir,” said a shorter one, with wide face and grey-blond whiskers. “But considrin’ the strange circ’stance, tis not surprisin’”.

“Are you expecting Andrew to come through the gate today?”

“Not very likely,” said the third, slender, older and grayer, “gi’en the way he was photographed yest’day.”

The officer was referring of course to the remarkable photo taken by Phil Noble of Reuters, showing Andrew slumped in the back of a police cruiser, as he was ferried back to his temporary home at Wood Farm in Sandringham. (He’s due to be moved soon to smaller, damper, Marsh Farm nearby.) The picture was on the front page of every newspaper in Britain (print and online editions) and thousands more abroad. Eddy Frankel, art critic for The Guardian had a field day:

“Those red eyes, like two little portals to hell, are not angry or vicious: they are dazed and overwhelmed. They’re the same eyes you see in the anguished howler of Edward Munch’s The Scream or Gustave Courbet’s Desperate Man.”

Frankel went on extravagantly, comparing the photograph to paintings and graphic art by Francisco Goya, Otto Dix, Francis Bacon and oddly, Juan Carreno de Miranda, a now little-known painter at the 17th court of Charles II, much inferior to his predecessor, Diego Velazquez. Had Mr. Frankel popped the photo of the sinking Andrew into an AI search engine?

Until recently, art history students were trained to memorize thousands of images precisely to perform the task of discovering resemblance. The idea – premised on the mostly correct assumption that art is derived from other art – is that once you recognize the pictorial bases of your target image, you can judge if they share a similar meaning. Like young physicians trained to recognize symptoms, art history students must exercise caution. Just as chest pains could mean a heart attack or indigestion, an image of a man with wide open eyes and folded hands could mean either terror or amazement.

Regardless of how Mr. Frankel came to his judgment of likeness, I think his interpretation is faulty. What we see in Noble’s photograph is not the “shock, pain and horror” found in associated works by Goya, Munch, Bacon, et al. What we see is simply surprise: a son caught pinching money from his father’s wallet; a student spotted cheating on an exam; or a husband discovered by his wife in the arms of another woman. Note the red-eye effect of the camera flash, calling to mind a succession of movie gumshoes (Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep or Jake Gittes in Chinatown) employed by suspicious wives, husbands or fathers to catch and photograph their cheating spouses or errant daughters.

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor was arrested (though not charged) on suspicion of selling commercial secrets to Jeffrey Epstein (“misconduct in public office). He was spotted and photographed in a police car, returning from Aylsham (a pretty and prosperous village) after being booked, fingerprinted, DNA swabbed, and interrogated. His mug-shot was taken. Andrew had been Prince, Duke of York, and the Queen’s favorite. She appointed him roving, trade ambassador — “Air-Miles Andy”, the tabloids called him. Now he’s just another punter. That’s why he looked so surprised in the photograph.

“Happy Jew Year”

The Epstein Library, as it’s innocuously titled on the U.S. Department of Justice website, is a miracle of simplicity. Just put in your search term and you’re off to the races. “Trump” has 5,240 results and “Andrew” 18,818. (Some of Trump’s have been excised.) It’s unclear if people with most hits are most implicated in Epstein’s criminality. Chomsky, distressingly, has a whopping 6,322 results, though the vast majority are duplicative or innocuous.

To test the site’s functionality, I decided to search the term “Jew”. Epstein was Jewish, and so am I. And so were many of Epstein’s friends, patrons, beneficiaries and confidants. They included intellectuals like Chomsky, Larry Summers, Steven Pinker, and the late Stephen Jay Gould. Among his Jewish friends from the financial world were Les Wexner, Leon Black, Ronald Perelman, and Ronald Lauder.

Did the emails and letters reveal some shocking, Jewish penchant for pedophilia? Was there anything Jewish at all, I wanted to know, about Epstein’s gatherings in New York, Paris, Santa Fe or the U.S. Virgin Islands? Did he and his distinguished guests come together for Shabbat dinners, to celebrate Rosh Hashanah or read the Haggadah at Passover? Did they study Yiddish language or literature, read the great Jewish sages, Maimonides and Hillel? Did they form Marx and Freud, or perhaps Saul Bellow and Philip Roth reading groups? Roth published in 1958, a comic short story called “Epstein” about the Jewish owner of the Epstein Paper Bag Company who contracts syphilis and shames his wife and family. That would have been a good subject for dinner-table discussion.

But no. There was nothing particularly Jewish in the 3,551 search results for the word “Jew.” What there was instead was innumerable news digests supporting the latest Israeli atrocity against Palestinians. There was also a lot of badinage between Epstein, his staff and a few friends (most but not all Jewish) containing every imaginable anti-Semitic cliché or canard. Cheap Jews? Check. Jewish clannishness? Check. Jews as shadowy, financial puppeteers? Check. Jewish intellectual superiority? Check. Jewish racism? Check. Here are a few examples:

Roger Schank, a pioneering AI researcher and university professor (now deceased), wrote to Epstein:

“You want genius shrvarters? I didn’t promise that, nor could I have.” [Schank means schvartzes – a derogatory Yiddish term for Black people.]

Epstein later wrote back:

“This is the way the jew [sic] make[s] money and made a fortune in the past ten years, selling short the shipping futures, let the goyim deal in the real world.” [Goyim is a mildly derogatory term for non-Jews.]

Then there is this cheery message, from name redacted to Epstein:

“Saw Madonna on the Jew Larry King show, talking about ‘Qaballah.’ Hollywitz types, especially gentiles, who take ‘Qaballah’ lessons from some Rabbi huckster are a funny joke. Larry didn’t look amused [… ] Not that he gives a damn about any spirituality including kike spirituality.”

German business consultant David Stern, friend of Epstein and partner with former Prince Andrew, wrote about his upcoming plan to come to NYC:

“Flights are quite full so the sooner you OK our Monday meeting in NYC, the cheaper for me…. Jew is jew…. Thank you !! “

Venture capitalist and (Gentile) publicist Masha Drakova wrote to Epstein in 2017, flattering his intelligence and penchant for eugenics:

“The more Jew you are the smarter. You said you’re 98% Jew. You’re very smart. My ex-boss is 78% Jew. He is super smart, less smart than you are. I have a close friend/business partner who is 99.3% Jew. He is crazily smart. We take all Jewish people… ask them to do 23&me test. Do event for everyone who is 98% Jew.”

Epstein had plans to use his Zorro Ranch near Santa Fe as a place to inseminate young women and create a colony of mini-Epstein geniuses. Was he inspired by The Boys from Brazil, the 1978 film (from the Ira Levin novel) about a plot to create clones of Hitler?

In January 2013, comedian Alan Slayton wished Epstein “Happy Jew Year.” (The Jewish New Year falls months earlier, during the two-day holiday of Rosh Hashanah.)

And there’s this sexual insider joke, sender’s name redacted:

“I’m a Jew..do you remember? :))) No sharing…hahaha”.

Peggy Siegel (entertainment publicist) writes to Epstein about a planned party, probably in New York:

“Is it going to be 100% Jew night? Even Perelman on Yum Yum has some goyum [sic].”

Perelman is the billionaire banker and investor. “Yum Yum” is code for Epstein’s Caribbean Island.

And finally, Epstein sends the following note to an unknown recipient – possibly just himself. I leave his bad typing intact and hatred unfiltered:

“1 wrinkly old hag, just because she is ri=h she thinks she can talk down to everyone. . five=towns neauveau. a real piece of shit. dumb as a ro=k. everone knows her husmbad insfunkcig young russians e=eryone except her. nasty cunt has some use service entra=ce..”

This represents pathological insecurity. An older woman, from the wealthy, mostly Jewish, “Five Towns” area on the south shore of Long Island, New York, has condescend to Epstein! Though a college drop-out, he counts among his friends the best and the brightest in the sciences, arts, politics and business. She’s a “nasty c—t,” he says, and deploys a double entendre: “Service entrance” is slang for anal sex.

There’s no Jewish conspiracy in these messages. In fact, there’s nothing Jewish at all in them. Vulgarity has no nation. Misogyny knows no religion.

The Massacre of the Innocents

On Dec. 10, 2010, Epstein’s assistant Sarah [last name redacted], wrote on her boss’s behalf to James [last name redacted] of Ocean’s Bridge Art, inquiring about the purchase of a copy of Cornelis Cornelisz Van Haarlem’s Massacre of the Innocents (1591). Epstein was evidently prompted to buy the copy after receiving a letter, two weeks before, inquiring if he could assist a “notable collector” sell paintings by Rubens and Caravaggio. The writer [name redacted] said that an earlier Rubens sale of a Massacre of the Innocents to the National Gallery of Canada in Ontario, fetched more than $40 million.

James was apparently surprised by Sarah’s request:

“Could you let me know what the painting is to be used for, and whether it is

ultimately to be framed or mounted?… If I have a clearer idea of the intended use, I may be able to make recommendations on the size of the painting and canvas.”

“Thank you for your reply!” Sarah enthused: “This painting will be framed for use in a private residence…. could you…give me a quote on both the 12 ft. size and the 9 ft. size?”

James answers: “These are 100% oil painted, in the traditional way…. 9 feet by 9 feet 5 inches – $1999. 12 feet wide by 12 feet 6 2/3 inches $3479.”

Seeking more particulars, Sarah writes: “Hi….I’m interested in getting the 9 ft x 9ft 5inch painting and am wondering if you have ever painted this particular painting before?…”

James replies:

“We haven’t done this particular painting since 2005….Please note that our clients have included museums, interior designers, galleries and over 10,000 individual art lovers. Our art work [sic] can be found in various hotels and restaurants, and even in the Venetian Hotel and Casino (Canaletto paintings of Venice, naturally enough…!)”

“Great!” Sarah answers. “Thank you. We would like to proceed with ordering the 9ft x 9 ft 5 in size of Massacre of the Innocents 1591.”

A few months later, Sarah writes to her associate Rich:

“Jeffrey is asking if you can Fedex the painting he had made of the Massacre of the Innocents to the ranch. It’s the large 9’x9′ canvas that we had rolled out for him to see in the entry way where they are killing babies. He wants to use it on the ranch and is hoping you could Fedex it to arrive by Wednesday?”

Here it is, with the original 1591 work by Cornelis shown below it:

Painted copy of Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem, Massacre of the Innocents, 1591. Ocean’s Bridge Art: Photo: Department of Justice.

Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem, Massacre of the Innocents, 1591. Mauritshuis, The Hague, on extended loan to Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem.

The copy is faithful but lacks the vividness of the original. The musculature of the nude men is lumpy rather than taut, and the terrified expression of the mothers, for example, the one in foreground right, is vitiated. Still, all things considered, Epstein had reason to think his $2,000 was well spent. (The copyists, located in China, and must be paid a pittance for their considerable skills.)

But why did Epstein choose this subject for reproduction and display? That a sex offender – he was convicted just two years earlier of soliciting sex with a minor — would commission a painting of naked and murdered babies is to say the least, surprising. It suggests Epstein was confident that neither police nor probation officers would call on him, and that guests at his ranch would forgive his mordant humor.

And why this version of the Massacre, and not better-known ones by, for example, Peter Brueghel, Peter Paul Rubens, and Nicholas Poussin? Cornelis’ Mannerist picture – there’s another version at the Rijksmuseum – is remarkable for its nudity and exaggerated foreshortening. The buttocks of the man in the left foreground, and the body of the infant below him whose throat has just been cut, are nearly perpendicular to the canvas plane, leading the viewer into pictorial space and projecting the foreshortened bodies into ours. Cornelis constructed a claustrophobic theatre of cruelty – note the way the pictorial space at the rear is narrowed by the arch – where women and children are controlled, rendered abject, and then killed.

Frans Hogenberg, The Siege of Haarlem and Spanish Executions, c. 1573-75, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

The painter himself was witness to such violence and nearly victim of it. As a child of 10 in 1572, he was abandoned by parents fleeing the siege of Haarlem. That’s when troops of Fernando Alvarez, 3rd Duke of Alva, killed all the citizens of the nearby towns of Zutphen and Naarden. The siege of Haarlem that followed lasted seven months, until the city at last surrendered. Though many residents fled, thousands more were rounded up and executed. Spanish Habsburg forces were finally defeated at Leiden and Alkmaar the next year. The Dutch gained full control of the North Brabant and in 1588 formed a republic.

Cornelis managed his trauma by reliving it in his two monumental canvasses of the Massacre of the Innocents. His maniera – a style pioneered by the Flemish Bartholomeus Spranger a few years before – precisely matched his own psychological needs, his “repetition compulsion” to cite Freud. As time passed and the Dutch Republic consolidated, Cornelis’s recourse to exaggerated expression and eroticized violence diminished. His later portraits and religious paintings are considerably more restrained than his Massacres. Epstein experienced no such maturation; he must have believed he had a kindred spirit in Cornelis.

What about the victims?

We may never learn what abuse occurred at Zorro Ranch near Santa Fe during Epstein’s more than two-decades residence there, or at his homes in Palm Beach, New York or Paris. Some accounts about Zorro emerged during the 2021 sex-trafficking trial of Ghislaine Maxwell. One witness, assigned the name “Jane Doe” to protect her privacy, testified that she was 14 when Maxwell coaxed her to Epstein’s Palm Beach home and subsequently Zorro Ranch to perform sexual favors for them both. Annie Farmer said she was 16 when both Maxwell and Epstein abused her at the ranch. (Her age in this case is immaterial since the age of consent in New Mexico is 16.) Another “Jane” alleged in an affidavit that Epstein assaulted her with a “device” during a visit (date uncertain) to Zorro Ranch when she was 17. (Again, it’s the assault not the age that’s important here, as far as the law is concerned.) Virginia Giuffre alleged that former Prince Andrew assaulted her in New York, the Virgin Islands, and in London, at Maxwell’s home in Belgravia. Her age at the time of these alleged assaults is unclear.

Discussion about these acts in the media, among politicians and the public is a holy mess. Anti-trafficking campaigners, feminist advocates, and many others are frustrated and angry that so much attention is focused on Epstein and the other abusers. “What about the victims?” they reasonably ask. It’s not clear how this question is being answered, except by lip service, of which there has been an abundance. Criminal prosecution would appear to be the best response, but this has so far proved challenging. Epstein himself served time in prison, was prosecuted a second time, and committed suicide rather than face the likelihood of another conviction. Maxwell is currently serving a long stretch in a prison (however gilded). Most of the other individuals (all men) accused of sexual assault are now dead. Of those that survive, their accuser is dead. There is vague talk about other abuse survivors in ongoing discussion with federal and state prosecutors, but so far, no charges have been filed and nothing about the cases has appeared in the press.

Adding to the prosecutorial challenge is the five-year statute of limitations for federal sex crimes, excluding those involving minors, below 18 y.o. There are as many variations in state statutes of limitation as there are states, though nearly all have no limitation when the victim is a minor. As a matter of justice, however, that may be the worst possible exception to statutes of limitations. So called “implantation studies” indicate that about 15-20% of subjects can be induced to accept a false memory of trauma, including sexual assault. Adding to that confusion, large majorities of clinical therapists believe that repression of traumatic memories can occur. This despite the fact that there is little scientific evidence for the existence of unconscious repression or successful suppression of traumatic experience. In sum, traumatic experiences aren’t easily forgotten, but they can be created.

Further muddying the waters is the mostly undiscussed question of prostitution. It is illegal almost everywhere in the U.S., though variously defined and prosecuted. In some places, buyers of sex are targeted, and in others, sellers. In some, minors are exempted from prosecution. In Maine, adult prostitutes may not be charged, though their Johns can. In Louisiana, convicted prostitutes are put on sex offender registries.

The definition of trafficking differs equally widely according to state, though inducing a person under 18 to have sex falls within that category everywhere. The federal Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000, has a similar age limitation. Federal anti-trafficking laws, therefore, don’t protect people over 18. That may be the age of many of the women, according to the DOJ files and anecdotal evidence, transported to Epstein residences. In any case, so far it’s unclear how many of the women used by Epstein and cronies were prostitutes (willingly engaging in sex for money and of legal age) and how many were trafficked.

In U.S., crimes again persons and property are treated as attacks upon the state or nation, not the individual. The plaintiff is always the “People of the State of…”, the “Commonwealth of…” or simply the “U.S.”. Though the Constitution doesn’t specifically disallow private prosecutions, Supreme Court rulings have clearly affirmed that “a private citizen lacks a judicially cognizable interest in the prosecution or non-prosecution of another.” The crimes alleged in the Epstein (et al) cases — rape, sexual assault, trafficking, and the rest — are violations of the common good. The community’s sense of security is violated when any single person is criminally harmed. However, some breaches of the common good may be better addressed in the political than in the legal arena.

The reason Jeffrey Epstein and friends were able to do what they did for so long is that they were immensely rich. Owning multiple expensive homes, airplanes, fleets of cars, and having at your disposal servants, assistants, bodyguards, lawyers, doctors and other professionals, means that you are insulated from the contingencies of life that affect other people. It also means that you have friends everywhere who – for a price or simply the reflected sheen of lucre – will do almost anything for you. Can we really expect anyone employed or supported by a billionaire to blow the whistle on him? And if not a servant, gardener, or accountant, why a policeman or politician? Do we really expect the super-rich – the top 0.1% of the population which possesses 14% of the nation’s wealth – to be subject to the same laws as the rest of us? What about the top 0.00001 of the population (just 19 households) that control 12% of the nation’s wealth? Great disparities of wealth are inimical to justice, and if we really want to end impunity and “support the victims” of sexual and other abuse, we need to tackle inequality. There’s simply no other way.

I felt out of place among the photographers and journalists at Sandringham last week, and a bit ashamed. How ludicrous the whole spectacle seemed, and how exploitative. Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor was arrested for misconduct in public office – though not yet charged. He’s been stripped of all titles, and even if he avoids prison, his life is ruined. The same is true for Peter Mandelson, former U.K. Ambassador to the U.S., former Business Secretary, former Minister without Portfolio, former member of parliament, former architect of New Labor, and so on. He’s still a life peer, but probably not for long. He may end his days in prison. I don’t have sympathy for him or Andrew, but neither do I feel good picking at their bones.

What I understood at Sandringham but couldn’t convey to my fellow journalists was the following: “You are missing the real story here. It isn’t that Andrew still lives at Sandringham, in however straightened circumstances, but that a private estate of 20,000 acres can still exist in a small country like the U.K. The crime here isn’t that Andrew passed secret, financial information to Jeffrey Epstein, but that he and his family and many others have access to such knowledge all the time and make active use of it to enrich themselves. The real crime is that the likes of Bill Gates, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Ron Perelman, Ronald Lauder, Leon Black and so many others in and out of Epstein’s orbit, make vast amounts of money without producing a single thing of social utility – that they can consume so much and contribute so little to the welfare of their fellow Americans. The reckoning for Epstein’s circle – if it comes — won’t be in the courtrooms but in the voting booths and in the streets.