WORD OF THE DAY

Queer Anarcho-Communism:

In this essay, I hope to put forward a queer anarchist communism for the 21st century and beyond through various lenses, particularly of Fredy Perlman, Walt Whitman, Bæden’s Journal of Queer Heresy, and the authors of the anarchist magazine Mother Earth. A queer anarchism: an event gives rise to multiplicities of duplication that emerge from the singularity of each event. Queer anarchism: like the Tom Vague’s The Boy Scout’s Guide to the Situationist International says, there is no situationism, there are only situationists (3). Queerness is something someone can take up at any time; queerness is analogous to Plato’s instant, which he speaks about in Appendix to Dialogs 1 and 2 of the Parmenides - the moment outside of time, which allows for change. The instant is called a “queer thing” in the Gill and Ryan translation (Plato 163). It is the indestructible chaos of timeless things, as Molloy describes of the moon in Samuel Beckett’s Molloy (41). Queerness is authenticity, in that queerness is the Platonic instant outside of time. This is like immemorial time for Deleuze, which is everything in sense that sense produces in consciousness, which is prior to the time experienced by consciousness phenomenologically. This is why authenticity has an unconscious basis, as it is the unconscious which returns as a geological, unconscious phenomena. It is the instant of the break with the socius. Queerness is escape from capture, and straightness is the capture into the Leviathan, the eternal undead superorganism which is, as Perlman says, a locus of death, in that it is the death which captures our potentiality and makes us stiffen in accordance with its artificial life (68). The Leviathan is contrary to what Hegel describes as the life of the “organism of the state” in the Philosophy of Right (240). Gender is capture into the Leviathan, and queerness is freedom.

Linear time in Against His-Story, Against Leviathan is in time and is Leviathanic (Perlman 241). It captures potentiality through segment breaks, which cut into the flow of temporality and order it based on the artificial time that is produced by machines. On the other hand, cyclical time is “rhythmic” (241) and outside of linear, scientific time, and is where the moment of change not produced by the state occurs. The moments which are internal come from the instant and the creativity which is not in time, while the Leviathanic capturing of our bodies into the flows of mechanical time cut into the flow of cyclical time. It is easiest to think of everything happening in this essay as just two things, broken down into many different forms; the two things actually happening here: in time, and outside of time. Consider a 1 representing a unit of time, and a 0 representing the segmented parts outside of time which do not construct a whole subject.

The instant is everywhere; it is not coterminous with anarchism necessarily. The instant is the governing principle of change, outside of time, the unconscious. It is not necessarily good or bad, while anarchism is an expression of a desire which aims towards a good or a bad at any given time; but the instant, and queerness itself which is outside of time - not in the sense of being another place, but rather being coterminous with everything and allowing it to change - is beyond good and evil. In a sense, queer anarchism asks that we be open not necessarily to changing our minds whenever someone insists, but rather a society in which the state and its boundaries do not capture people like the triangulation of Oedipus in the prohibition that arises whenever someone is going about their day and all of a sudden, they must change their direction in accordance to the state’s invisible lines. These are sorts of things we must do every day, and they are tied directly into things like working in a capitalist system. In a capitalist system we do not have autonomy because we do not organize our own workplaces. We do not have the freedom to develop our individuality unless someone is wealthy; this often comes from inheritance, and much less often comes from “moving up the ladder.” Whenever people do “move up the ladder,” they will angrily spew down hate and bile on the people eagerly trying to climb up behind them, saying that they are asking for too much. In a capitalist society, the principle of change is met with the principle of representation, the micro-fascism which organizes things into a tension dictated by its symbolic code. For instance, going to work, being nice to a boss who has no right to have any power over you, but is merely in his place of power because of the violence that colonized into being things like the teacher, the boss, the cop, etc. Not just a colonization of the past, but an ongoing colonization in which we must put on masks and armors and perform the tensions through our muscles, the labor of the pigs and their paranoiac “master” fantasy.

The offer of freedom which is not a paranoiac fantasy is something which queer communism offers. It is queer because the instant which allows for change is what is focused on. The instant is queerness. Queerness represents change, while temporality represents ossification on an abstract timeline, as all linear time is an abstract machination. The state, likewise, is like a clock or time, in that it works internally, and you are free up until the point at which you act in accordance with it. Perlman describes how monks designed the clock as a mini monastery; springs and wheels of metal, not flesh and blood (155). You pivot on the structure of linear time in the symbolic order, so to speak, in a state, whereas the instant is the moment of the unconscious, coterminous with time but also not in time, as motion and the sense which comes prior to conscious experience, that produces conscious experience in the instant: linear time of the state, which is Leviathanic, is not the instant of immemorial time which produces the conscious experience of time. Because time is always conscious, and operating in according with it requires internal tensions and armors, through which one acts as an automaton, without authenticity in an atomized, as opposed to individualized life. Oscar Wilde says that we develop our individuality the way Jesus wants us to develop our personality; not through materialism and continual acquisition, but one’s internal state:

He said to man, “you have a wonderful personality. Develop it. Be yourself. Don’t imagine that your perfection lies in accumulating or possessing external things. Your affection is inside of you. If only you could realize that, you would not want to be rich. Ordinary riches can be stolen from a man. Real riches cannot. In the treasury-house of your soul, there are infinitely precious things, that may not be taken from you. And so, try to shape your life that external things will not harm you. And try to get rid of personal property. It involves sordid preoccupation, endless industry, continual wrong. Personal property hinders individualism at every step.” (Wilde 390)

Wilde uses the examples of Shakespeare and Shelley as people who have achieved individuality (392-93). Individuality is the motion through which one is relaxed, free. Learning this way is how Francisco Ferrer’s “new school,” in the essay “L’École rénovée,” published in Mother Earth, hopes to develop in students the internal capacities they need to go beyond capitalism; we might interpret the “natural bent” as a Wildean individuality Ferrer is trying to produce in the student:

We can destroy all which in the present school answers to the organization of constraint, the artificial surroundings by which the children are separated from nature and life, the intellectual and moral discipline made use of to impose ready-made ideas upon them, beliefs which deprave and annihilate natural bent. Without fear of deceiving ourselves, we can restore the child to the environment which entices it, the environment of nature in which he will be in contact with all that he loves and in which impressions of life will replace fastidious book learning. If we did no more than that, we should already have prepared in great part the deliverance of the child. (Ferrer 263)

Capitalism, and the state which upholds it, is restrictive. It’s akin to the Leviathan sticking its incorporeal tentacles into your brain, similar to Heidegger’s ready-to-hand - how we grasp the possibilities of our world and connect to things as extensions of our bodies. The tentacles connect to us ready-to-hand, and they push against the not-I. To be yourself in capitalist society, you must continually try not to be yourself, in order to break down the fantasy which capitalism has instilled in you, of what it wants you to be. The representational image of you, given to you by society, is a fixed idea, a representation, an ossification, and a lie in that there is no person except an ever changing multiplicity, through which one connects as machinery, or authentic Dasein incorporating the past and future into the moment of the present, and choosing authentically what one wants to do without pivoting on the moment of choice on the machinery of the state. The world spirit once again hungers for freedom, it yearns to be released from the bubble under the earth, in the geology of the contradictions of the recording surface, which at every moment burst forth at the seams of capitalism. The time has come not to throw away our books and rally in the streets, but to focus on how to build a new queer communism from the rubble of the tyrannical fascist empire, once it begins to fall. One might say that there is always queerness in things which can never be contained in the mere categories of man or woman, or non-binary, or beyond. Queerness is everything which breaks free of the Leviathanic molding through the tentacles which attach, ready-to-hand, through representational impositions. As in, when someone tries to impose representation onto you, they are molding you into something and in a sense everything which we are told is in a way a mold from something that came before. Words themselves connect to a long chain, a ball and chain of world history. But if one cuts the Gordian knot of history – where one cuts into the timeless, which is in between the temporal flow of linear time’s past and future at the instant of change – one realizes that there is no gay or straight, as these are dependent on representational categories which order someone in such a way that they are queer only in the sense that there is a moment of queerness in their acting. A full queerness does not have the ressentiment, or the Nietzschean debt that one pays in The Genealogy of Morals (Nietzsche 45), through their expression of man or woman, to the gaze of the big other in the socius. One is good or bad in regard to the socius and its dominion over what is good and evil. To go beyond good and evil is to embrace the indestructible chaos of timeless things.

Full queerness would be living according to how you want without being inhibited by outside forces which order you in such a way that you cannot order yourself. A communist society would therefore be non-hierarchical, although it would not eliminate hierarchy in the sense that everyone would still have some things that they are better at, or more attracted to, or things of this nature; but the institutional forces under queer communism would be such that they do not do something similar to autistic masking, in that it does not make people obey a hierarchical structure in which they do not organize their own lives. Without democracy in the workplace – the place where we spend most of our lives – and the ability to have the resources to live comfortably and do what you want to do, people become merely at the advantage of the wealthy, who control the business. The worker who can merely be fired because they are an insignificant, atomized cog in a machine. We do not need rulers; this means that we do not need people governing our lives. Capitalism is incoherent to a queer anarchist view because it does not allow for queerness. So, being a rich queer anarchist, you are not authentic in just being gay under capitalism, you are actively participating in a system – one which may be maximizing your own individuality, but it is an individuality which is not one in which you have no masters, unless you are the mega rich in America’s two-tiered justice system, as shown with the election of Donald Trump. The Center for American Progress also did a study showing that the United States criminal system punishes the poor, and rewards the rich (Weller). The poor person has a “tyranny of want” (Wilde 384); meanwhile, the rich take the wealth of the poor and order their lives like machinery. Leaving the master’s in place means we do not order our own lives, and instead are ordered. There is no freedom, comfort, and security, when there is a tyrant who orders your life and takes your wealth. In other words, even those who are middle class in America are in a system in which they must abide by the decisions of whoever is in power. The government should not have the right to tell people to do anything; if there’s an institution that does anything other than distribute, such as administrate, then it is not the sort of non-administrative state which Wilde talks about in “The Soul of Man Under Socialism” (395) .

Having it both ways, with representation and timeless chaos, means carefully aiming one’s intentions, like a bow and arrow, towards the goals that one wants to achieve. Sometimes it is better to be full of motion; sometimes it is better to be silent. You would not want to do things that would get you arrested in front of a police officer if you have a further intention to do something that does not involve being in jail. So, having it both ways means carefully navigating yourself in a world which tells you that you should “be yourself” by going along with what teachers think, and with what the powers that be think, by getting a job, and owning a house, and living under the spectacle which is the guardian of sleep, the dead thing which leeches off of our authenticity which Perlman describes as the Leviathan (37). One is authentic by not being oneself, by continually breaking down the representational image given to one by society and exploring new avenues of interest. Money is not an endless well of happiness; according to Penn

Today, after a certain income, money does not bring more happiness; happiness rises steeply, and then plateaus after a certain level, around a $100,000/yr salary (Berger). Yet certainly, having wealth gives people the opportunity to “be themselves.” This is not a universal authenticity, in the sense that it is queerness that is the instant, as being themselves does not mean plotting their own course in life; it rather means that being in a society where many of the ways in which you are yourself conform to the options which are provided for you by society. This is a society which promotes inauthentic expressions of the capture of psyche to advertisements which entice you to buy things; they stick the tendrils of capital into you, the product to be sold on the market of corpses in the Leviathan’s cities and towns, which are the Leviathan’s entrails, which are the “surplus product” and “material contents, its entrails” (Perlman 29), while the form of capture is the bodily and spiritual condition that people live in under the Leviathan (71).To envision a better future, is to believe that we can be not ourselves, but break down our societal heritage and begin to construct ourselves.

Believing that it is possible to construct a better world is to believe that there is a way in which we could exist in which we do not need to mask against our own nature. Not in the sense of lording ourselves over others, but in having the ability to develop our inner capacities, and the external conditions which enable people to develop their internal capacities. Zoe Baker describes internal capacities in Means and Ends:

A capacity is a person’s real possibility to do and/or to be, such as playing tennis or being physically fit. It is composed of two elements: (a) a set of external conditions which enable a person to do and/or be certain things, and (b) a set of internal abilities which the person requires in order to be able to take advantage of said external conditions. (50)

External conditions as well as internal capacities give people the ability to do things such as play music, or build things, or write beautiful literature, or become knowledgeable in history; there are so many things which one could do which would be embracing the sort of individuality that Oscar Wilde spoke of in “The Soul of Man Under Socialism,” where people do not simply conform to other people’s thoughts and attitudes, but develop their own individuality (393). Developing a personality is not expressed as an individualism through a molar person which can suddenly emerge as if from a jack in a box to say hello, fully formed, only to be folded back into its own spine like an accordion to pop out again. Individuality is unique, and it comes from having the ability to develop the capacity to live an authentic life. Uniqueness is outside of time, and it is part of the a-signifying semiotics of the recording surface, which determines everything we consciously think. Creativity is not a conscious process; everything that makes an artist like Beckett interesting is certainly not that somehow his works tell us something about him. Creativity is an expression of the chaos which can be recorded miraculously into the recording surface and then duplicated out of the singularity of the event. Sometimes duplications have dead and undead consequences, such as Leviathan, and queerness. The undead consequence of when queerness produces representation can produce more queerness as a consequence, as well as dead consequences. The dead consequences would be representational capture and ready-to-hand connection through machinic tendrils of the Leviathan which order a person against their individualism.

Constructing ourselves does not mean doing whatever you want, whenever you want. It means developing an internal personality which is satisfied with oneself in the cosmic context in which one lives. Just as you would not want to do things all the time which get you in trouble, even in the context of an environment which you disagree with. It is sometimes said that coolness is going far enough that you bend the rules without breaking them. Breaking the rules is uncool, and it shatters the symbolic order. The symbolic order is a comfort which is applied to people’s worldview, which gives people a wholeness that is threatened and can produce aggressiveness; as Lacan says in the Écrits, aggressiveness occurs when the imago is fragmented (85). The imago is the imaginary wholeness which covers up the lack of the symbolic, which, if we remember Shiva, is not the productive dance of Shiva and timeless chaos; the lack of Lacan is produced by capitalism, and the desire to enjoy excessively. Capitalism is continually encouraging people to enjoy themselves excessively. Think of the Big Mac at McDonald’s; think of the constant drive to get rich, as opposed to the drive to help others. So, being yourself does not even mean being yourself in the sense that you are connected to some sort of internal dynamo or centrifuge of command. Being yourself means not being yourself, as taking on numerous connections, in a nomadic manner, is a way to appreciate the art of the world that one would otherwise not discover, like Sun Ra , or anarchism itself. One cannot simply exist in a world and be an anarchist. Like capitalism has pivot points, communism should create pivot points that grow out of the individual. A pivot point is the idea that temporally, you pivot off of the symbolic possibilities which offer themselves to you, and judging on the symbolic possibilities, one can pivot off of the temporality of the state for the purpose of achieving a further down the line goal of not having a state. It is kind of like how you wouldn't want to pick a fight with a police officer if you did not want to go to prison. Pivot points that emerge out of the internal capacity of the individual are less alienating than the atomized labor under a boss of the laborer, because under communism they set their own commands. Communism means having the ability to have time off of your work, which should be fulfilling – not a bullshit job which only exists for the purpose of making more money. There should not be a need to continually produce merely for the sake of producing; rather, if we have the technology to lessen work, then technology should provide comfort by taking away the time which people would otherwise devote to work, giving it to machines, so that people can pursue their own desires.

Life is not a job; doing things for the purpose of a job is not a life. Perlman talks about how Christians came up with the distinction between work and play because they were infuriated with the peasants for being too free (9). It was sinful to let people just run around without any sort of work ethic. There should be no distinction between work and play. In a cosmological context which made sense, we would look at how to maximize what we can give back to nature and minimize our footprint on the earth. This is in both the sense of a carbon footprint, but also in the sense of how Perlman talks about nature playing a role and giving its gifts, and people playing their role and working within the rhythms of nature (178). The earth and its communities produce the parts of the “meaningful context” and when these rhythms are broken, “meaninglessness” is produced (178). It is a symbiotic and harmonious view of the human community which Perlman gives. You cannot help the world before you help yourself, but helping the world is helping yourself. The world being a place which promotes help towards others, is a world in which help towards others, is received back to you. A common proverb says, treat others how you would want to be treated. This does not always work; some people are masochists, or narcissists, so one must adjust accordingly. But, aiming for the mean, doing the thing which each context calls for, is the way to maximize individuality. Doing whatever each situation and context calls for - that is how one aims a bow. One looks at the distance of the target; one shoots down the line. Queerness is what to aim for. It cannot be right-wing ideology, as right-wing ideology is looking toward the past, which means it is representational. Representation means something which came before, and it is arborescent, while queerness is a break in time, the instant, or moment of change, which is always occurring, but what matters in the instant is that it is the moment which is not in the past or the future. Sometimes aiming for queerness even means putting on a mask, speaking in terms of both Perlman’s masks and autistic masking.

Anything which includes machination - that underlying it and allowing it to have its motion is the queerness which gives things their motion. For Deleuze and Guattari there's a thousand tiny sexes, meaning at each moment there is a micro-trans-sexuality (213). Even if we try to conform to something like a gender, it is the indeterminacy which underlies it which gives it its determinacy, just as the death drive is the past experience of the ID repeating as superegoic jouissance, synonymous with the re-territorialization, or when the mind coheres into something coherent as a success of the desiring machines to produce a coherent conscious thought. When we think about the indeterminacy as death drive, we can see that Zarathustra was with us all along. Queerness evaporates linearity and illusions of division by measurement, which is the undivided nature which lies beneath. The geology of the unconscious, which emerges forth in various becomings, through the life which encompasses the history it incurs. We can see that once we cut the Gordian knot of history then there was the indestructible chaos of timeless things all along; it was never separate from the supposedly alien genders and their congealment.

Authenticity, and therefore queerness, is only possible if one understands history. History unfolds on the body without organs, which is the recording surface on which events are recorded - in marks, brains, and books. Each book is a body without organs; each recording device is a body without organs. But the body without organs is also a multiplicity of partial objects, analogous to dialog 2 in the Parmenides, when Parmenides talks about parts of forms where there are no forms themselves (Plato 147). History does not unfold from a Eurocentric spirit, such as

Hegel’s, but from the negative of what Hegel saw as the people with no spirit in the Philosophy of History – Africa:

What Hegel considers Africa proper has no movement or development to exhibit. It is ‘the Unhistorical, Undeveloped Spirit, still involved in the conditions of mere nature, and which had to be presented here only as on the threshold of the World’s History.’ (Adegbindin 99)

Here we can see how Hegel places Africa outside of his linear timeline, much like the instant. This is partially a paper about America, but the world spirit, if there is such a thing, would be unconscious – the indestructible chaos of timeless things. Queerness is the escape from capture, as the capture is the resonance of these historical systems which are left unhealed in their marks and consequences, the historical trauma of a people which lives on through the material consequences of times gone by, inscribed on the socius, which is the excess of history, which is always compartmentalized as the various marks, signs, and symbols, which are issuing forth from the non-signifying semiotics issuing forth from the body without organs which contains the marks of the singularities of the events that unfolded on them, and continue to unfold out of the marks like a record’s grooves. The body without organs is a fertile soil, through which communism can grow, as right now communism is an egg. It merely needs to hatch into a new world, beyond the march of world history. History is a recording surface in which events are caught in the folds of the recording surface. The body without organs is part of regular bodies and regular organs, but it is a lot like a record in the sense of grooves and marks - material patterns which are resonances from previous historical events. The body without organs is part of a geology of the unconscious, which has no memory, and which is composed of partial objects, and issuing forth in its potential at the same time that it is actual. Authenticity, which is a moment of queerness, can only exist in the context of going outside of the prevailing symbolic order in some way. There is a moment of queerness in homosexuality and in transgender identity; they fall under the categories assigned by society which are considered by the fascistic body without organs to be the way one is intended to be by the rulers.

One might say “but I’m gay, or trans, and my gender is authentic.” Under capitalism one is a ward of the state; one has a number and a sex, which the state assigns to you. You are governed because of your gender by the state, such as needing to through all sorts of institutional hoops to get hormone treatment as a trans woman, and in some states not legally being able to use the restroom you identify with, as well as being openly discriminated against in a society which has the police of the gendered system within it. This is even a vigilante police. You can see it online, where almost every comment section on a public forum regarding trans people devolves into hateful spew against trans identity. Elon Musk said, referring to his trans daughter, that his “son” is “not a girl” and figuratively “dead” (Ingram).

Musk is an example of a despot who wants to enforce a sort of mandatory maleness over his daughter. He said that he was unaware that he had signed transition surgery forms for his daughter; now his daughter, in Musk’s eyes, is dead. Perlman talks about how Aristotle sees things through an “inverted lens” (Perlman 89). In the same way, Musk sees the freedom of his daughter to adopt a queer identity as a sort of unfreedom. Under queer communism, gender affirming care should be provided as mutual aid; a society which cannot provide gender affirming care is simply a society which cannot provide a complete healthcare to its people. For trans people, being trans is their authenticity, and for homosexuals, liking the same sex is their authenticity. Under queer communism, there would be no governance determining who can and cannot like someone, or who can dress a certain way; as putting codes on dress, aside from perhaps basic clothing, which even Margaret Grant argues is not a norm in some countries; they have no clothing, and they have higher sexual modesty

H. Crawford Angus, the African Traveler, goes so far as to say this: “it has been my experience that the more naked the people and the more, to us, obscene and shameless their manner and customs, the more moral and strict they are in matters of sexual intercourse.” But who wants to pay such a price for mere morality? (101)

I made up my mind that modesty was a thing of our civilization, and quite artificial it might be, but no less necessary for that reason; so I set about discovering what conduct was modest and what was not. (101)

What queer communism is more about is not instilling mandatory gender in anyone, and allowing people, from birth, to explore their own decision as to what gender they want to be. Yet queerness is not only an unusualness of people, bent as opposed to the dominant straight order, under the patriarchal Leviathan. Nature itself is a vast queerness; there are no lines in nature. But even though there are no lines in nature, people tend to tell others that they conform to a specific way of being, otherwise they are “not straight.” This is a certain “path,” as Sarah Ahmed says in Queer Phenomenology:

The relationship between “following a line” and the condition for the emergence of lines is often ambiguous. Which one comes first? I have always been struck by the phrase “a path well trodden.” A path is made by the repetition of the event of the ground “being trodden” upon. We can see the path as a trace of past journeys. The path is made out of footprints – traces of feet that “tread” and that in “treading” create a line on the ground. When people stop treading the path may disappear. (16)

Everything we think has a history and comes from somewhere. Speech itself is historical. If we did not connect to the past when we talked, we would have no memory and no speech through which to recall the memory. Speech itself is a repetition, a repetition which is new every time; it emerges from the past, a sublation of what came before, which takes it up into its conscious form, which is only the conscious part of what is happening. The unconscious part is everything that you do not see. Every event which unfolded in real time, in real life, that we only know about through books or screens, once they are recorded. People force identification on you all the time; they say “sir,” or “that man,” assuming what gender you are, or that you even claim a gender identity. If you are not a preconceived gender? That simply never crossed the mind of those who gender you when you do not use pronouns, which is interpolation into the symbolic law and order of the societal mask and armors which arrange themselves over the representational notion of gender. In studies of autism there is a term which might make Perlman smirk called “masking.” When an autistic person feels constrained by society to express themselves how they want to express themselves, and they have to put on a regular face - this is indistinguishable from Perlman’s notion of a mask and an armor. Someone who is armored against their true nature; as Perlman’s wife Lorraine points out in his biography Having Little Being Much, this concept comes from Wilhelm Reich (3). So, if someone has a gender, and they want to express this, it dictates what comes next from what comes before. This is a representational construct.

Representation is something which tries to copy what comes before, when ontologically speaking there is really only the flux of the immemorial time. Corporeal time is merely a constriction of the muscles, a contraction through which we pivot. Unlike jazz music, which might mix corporeal time with rhythmic time – the individual expressing themselves in a semi chaotic manner – one improvises the notes in which they play, as opposed to playing only what was written and came before. Jazz music is a perfect example of rhizomatic music that emphasizes queerness. Queer anarchism does not mean a wacky wavy arm-flailing inflatable tube person. It is taking the temporal and linear, and mechanical and cyclical time, steadying to aim the bow in the mean of the two to accomplish what one wants. There is never a need to gender someone if they do not identify with gender, but there is not a need to see linear time as completely good or bad, as good or bad only become a thing in linear time through which they can be measured as events which have a positive or negative outcome. In the immemorial time there is no good or evil, but consciousness produces values such as positive and negative ones. One experiences the conscious evil of linear time phenomenologically. Stress, anxiety, fear, anger, frustration, and high blood pressure are all qualities which can arise under a capitalist environment, and it continues to rise. “In 2024, 43% of adults say they feel more anxious than they did the previous year, up from 37% in 2023 and 32% in 2022” (National Alliance on Mental Illness). No one should be policed as to what they express themselves as, but insofar as one is copying something which came before, they are adopting a representation, which can, socially speaking, become a state apparatus in which people are controlled; or the representation becomes a merely social one in which people police and dictate to each other what it “means to be a man” or “means to be a woman.” Queer anarchism is not non-binary, as that implies being on a spectrum between man or woman. Man or woman is a representational ossification of the past which is not part of the Platonic instant in immemorial time.

There are moments of queerness - the state of nature, as nature is queerness itself in that it goes every which way and cannot be confined by perfect symmetry - in society, but they can only be momentary escapes and then a re-capture into the prevailing order without queer communism. Queerness, in part, is recognizing one's historic position in the context of a colonial society - the queerness, which tried to escape forth from the dam of Oedipus, the queerness which white power tried to destroy in the founding of America. This essay hopes to critique Whitman from within Whitman, by analyzing Leaves of Grass through the lens of Bæden’s Journal of Queer Heresy, and showing not only the problem, but the path forward through what a queer communism would look like. Now that a theoretical foundation for queer anarchism has been established, it is time to turn to Whitman. This section will establish a moral foundation for queer anarchism by showing that even someone who seems as inclusive like Walt Whitman can harbor a colonial indifference.

How Whitman goes beyond Heidegger, and Perlman goes beyond Whitman

Before Heidegger, there was a transcendentalist philosopher poet named Walt Whitman. I will interpret what Whitman is saying as a new philosophy, for the purpose of combining philosophy and poetry. Part of being a philosopher is recognizing that you are the book – you are not radically different, partially separated, or even somewhat separated. You are the book; Whitman spoke great truth when he said that he was all these things that he writes about. When you read a book, the thoughts become your own in how you interpreted them. In a way, you are the architect of reality. There are certain shapes and building blocks through which these architectural thoughts conform, but Whitman has the right idea: you are what you write, you are what you read, and you should experience your thoughts through yourself rather than the eyes of the dead. Whitman spoke in a language which was at once passive, in that things passed through him but were not him:

My dinner, dress, associates, looks, business, compliments, dues,

The real or fancied indifference of some man or woman I love,

The sickness of one of my folks – or of myself ... or ill-doing…

Or loss or lack of money… or depressions or exaltations,

They come to me days and nights and go from me again,

But they are not the Me myself, (23)

But his language was also active, in that he encompassed all things. In a time during the colonization of the United States and the genocide of the native Americans, there were ongoing wars between the factions of the United States who wanted to ban slavery and those who wanted to keep it. Whitman wrote the first copy of Leaves of Grass in 1855, just several years before the Civil War over slavery. Whitman wrote what is in my edition of Leaves of Grass a 20-page introduction. In it he says America was “discovered” as though there were not already people here (Whitman 4). Twice, once when he walks past native Americans, “the tribes of red aborigines” (5), and another when he mentions slavery, he says there’s those who are trying to protect it, and those who are trying to oppose it – Whitman does not take a side (5), he does not say anything as he passes about what injustices have been done. He also talks about how he does not judge the people who he passes: “He is no arguer, he is judgement. He judges not as the judge judges but as the sun falling around a helpless thing” (Whitman 6). This sets the tone for the work, and it marks a stark contrast with Fredy Perlman.

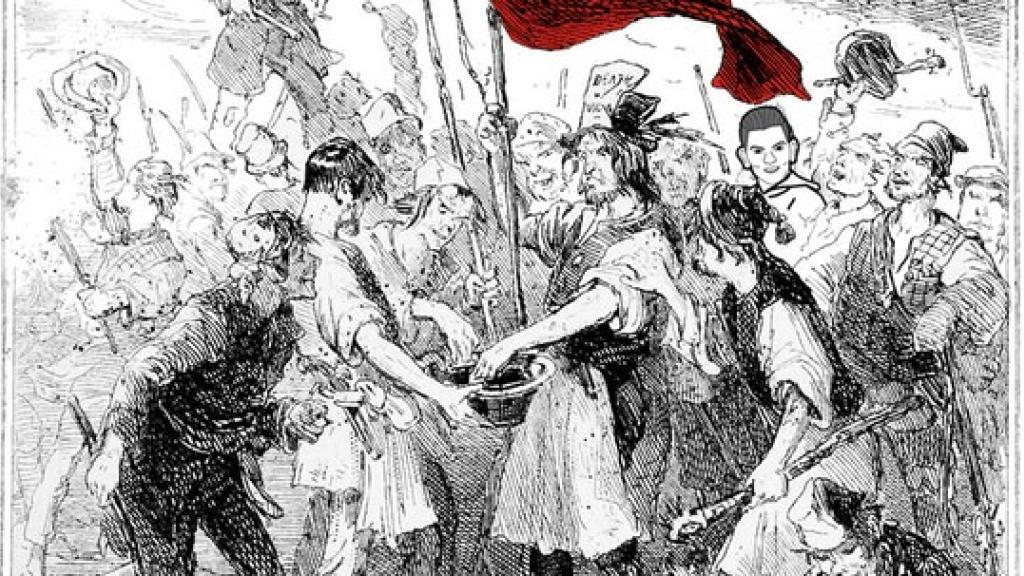

Compare Whitman’s attitude, walking through the American countryside, emptied of its native Americans, talking about how his spirit encompasses the spirit of the world. Fredy Perlman begins Against His-Story, Against Leviathan with Yeats’ rough beast, with a gaze blank and pitiless as the sun, slouching towards Bethlehem (Perlman 1-4). It is a story which is mythopoetic. It begins in the first civilization, Ur, in Mesopotamia. This is where the first Lugals, or male rulers, took over and began to write their his-stories (Perlman 24). Bæden, in the Journal of Queer Heresy, critiques Perlman from within Perlman for his use of the earth mother as the primal femininity that battles against the primal masculinity - which is phallus-shaped, like warheads and swords (Perlman 173). Bæden in the Journal of Queer Heresy says Perlman is being too essentialist (Bæden 34), while maintaining Perlman’s critique of the Leviathan. The Leviathan is undead – it is everything artificial, everything abstract. The Leviathan is excreted from rulers and people; it is the entrails of the mode of production. One can think of it as always deteriorating, in the sense that the Leviathan starts to crumble when people have not tended to it in a long enough time. The Leviathan is machinic organization, dominating the body without organs, which is the partial objects which the socius is caught up in. The most direct example of the body without organs is a book. Whitman does not show much interest in critiquing the world, but there is a sense in which Whitman is more Heideggerian than Heidegger.

Whitman goes beyond Heidegger in not detaching the authenticity of Dasein from the world; but, in Heidegger’s The Question Concerning Technology, he says that being is unconcealed in the artwork and not that the artwork is an expression of the artist (Heidegger 339). For Whitman, you become the world, you become porous; things pass through you; you are not them, but at the same time you “contain multitudes:”

“Do I contradict myself?

Very well then… I contradict myself;

I am large… I contain multitudes.” (Whitman 67)

And you are the grass, you are man and woman, all in the shape of becoming. Meanwhile, Perlman starts his book with an invocation against the beast, as explained above. This represents the difference in attitude towards colonialism between the two authors. Whitman seems to want to become one with the world. which is why Harold Bloom, someone who protected white supremacy in literature by his constant attacks on the “school of resentment” as he called them (4). Harold Bloom would probably call this healing literature. In How To Read and Why, he talks about the healing quality of literature:

Reading well is one of the great pleasures that solitude can afford you, because it is, at least in my experience, the most healing of pleasures. It returns you to otherness, whether in yourself or in friends. Imaginative literature is otherness and as such, alleviates loneliness. (Bloom 19)

He thinks that it is among the best literature on the continent of America. Whitman is enjoyable to read, but he can be frustrating. His indifference is something which we can see in the “objective” liberal scholar, who is indifferent towards the world; instead, hiding the history of white supremacy and patriarchy under a mask. This mask covers both the violence which they do to themselves, and that which people do to others through the perpetuation of internal and external violence. Bæden says taking off the masks and armors requires “almost superhuman strength” (127). Masks and armors for Perlman mean tensions which build up inside of people, and taking off the mask takes them close to the “state of nature.” He says that when you talk about the state of nature, “cadavers peer out” (7). People get defensive about their situation under capitalism; they tense up, they protect the system through perverse jouissance – the enjoyment of doing everything for the other – the big other of capitalism. There is a jouissance built into every action of capitalism, like in the cheap, momentary, and fading joy of buying something. It gives way to the sense of impending societal doom, each of us living in countries which might otherwise escape world trade and use their land and labor for the benefit of the needs of the people. It is not demanding too much for an author who boasts about freedom to espouse an anarchist ethic, like Perlman. Here we might say Whitman is doing something courageous in being openly bisexual in a time before civil rights for homosexuals had even begun. So, in a way Whitman does have a tremendous amount of authenticity, which we can learn from.

It is not that we understand Whitman’s true intent. We can never understand the intent of the author, or anyone else’s minds. The mind is silent; it is only words that speak, and words are already half dead. They contain the artificial notion of the fantasy of the other person’s mind, through which the machinations of your own impose the sorts of frameworks and phenomenological boxes that one cannot understand without having a one-to-one relation between the language, and importantly, the context in which the thought arose. Thoughts are contextual in memory, and phenomenologically speaking they are one with what we are saying and speaking. Whitman’s connection with the world around him is an expression of the multiplicity of the univocity of being, in which the hierarchy of being closer and further away from being breaks down, and everything is coterminous with being. Everything we read is inscribed onto the recording surface of our mind in traces, and in a sense, all of the world around us is just the order of the trace, the memory which composes the world. So, when Whitman says he is under your boot, and he is the pillow under a hunter in the woods, and he is man and woman:

I am the poet of the woman the same as the man,

And I say it is as great to be a woman as to be a man.

And I say there is nothing greater than the mother of men. (38)

He is saying that these things are not in books, they are not separate from you. They are you. When you realize the ready-to-hand possibilities of the world and the way in which you can relate to the world, there is no reason to take an alienated perspective: that the world is something different from you as an alienated monster, somehow separate and impersonally governing your life like a Kafka-esque nightmare. Instead of a shadowy bureaucracy, the Leviathan sticks its tentacles directly into your mind. It covers your very being in masks and armors which are coterminous with the movement of life underneath the Leviathan, which is so anxiety producing.

So, there is no way to say that something has a greater or lesser extent of distance from oneself; in that same way, there is no meta-language or meta-narrative from beyond one’s own perspective through which they can step outside of their own perspective and see Whitman’s. In that sense, Whitman has the right idea when he becomes one with the things he writes about. We can become one with Whitman, just as we can become one with a world in which the inner capacity to realize our individuality is matched by an outer world which is designed to develop individuality. Some people may feel as though, when reading a book, the book is separate from them, the knowledge somewhere else, and they can access it correctly or incorrectly. But the event, described earlier, is a singularity through which duplication occurs; it can be sometimes contradictory and oppositional. In the contradiction of the event is the authenticity of taking the mask off and operating as an individual, and the anxious, tension producing mask, of putting the armor on and operating according to ghosts. Here we might see also a Stirnerian parallel - the spook for Stirner being akin to a wheel in the head (40-43), making them essentially automatons, operating according to a fixed idea as opposed to having ownness. Ownness is likewise unique and not connected to world history, because it is outside of time, like the instant. For Stirner in The Ego and Its Own, this uniqueness is outside of world history:

To the Christian the world's history is the higher thing, because it is the history of Christ or 'man'; to the egoist only his history has value, because he wants to develop only himself not the mankind-idea, not God's plan, not the purposes of Providence, not liberty, and the like. (323)

Martin Heidegger wrote Being and Time, which does not chart the path of Dasein like Hegel’s world spirit, but rather shows a Dasein which is opposed to a they of the socius, the generalized other. The big other of Lacan is a good analogy - the generalized otherness of a society or group which is beyond your control and for Lacan composes the unconscious structure of language, which is the discourse of the other (Evans 133). Hegel’s world spirit operates on what Perlman would call linear time, which operates in accordance with a dialectic towards freedom in some interpretations of Hegel. In the Philosophy of Right, Hegel says spirit is not non-rational “blind destiny,” spirit is reason “in and for itself” which is developing out of the “concept of freedom” (316). This implies that spirit has a teleology and a correct path. States and individuals only judge imperfectly; world history falls outside of contingent judgments for Hegel (317). Whitman, like Heidegger, sees the past, present, and future as simultaneous. Heidegger has an indifference towards ethics. For Whitman, he has something which Heidegger does not have. He has authenticity through more than just Dasein. For Heidegger, only Dasein has authenticity, or being towards death. Whitman says to see through your own eyes, as opposed to the eyes of the dead:

Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems,

You shall possess the good of the earth and sun… there are millions of suns left,

You shall no longer take things second or third hand… nor look through the eyes of the dead… nor feed on the spectres in books,

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things from me,

You shall listen to all sides and filter them from yourself. (Whitman 22)

This is an authentic act: seeing not through the machinations of someone else, but through your own interpretation, your own radical subjectivity. In the film The Battle for Algiers, based on and using actors from the revolution, the guerilla factions and federations were initially unsuccessful, but it was finally the uprising of each Algerian person that threw off the French colonists. It was their radical subjectivity breaking free from the inauthentic regime. Things are not simply unconcealed to Whitman; he sees things through his own eyes and calls upon us to see through them as well. Whitman as well, as he encompasses everything, contains multitudes. Whitman was a medic in the Civil War, so he cared enough about people to try to save their lives. This is a contrast to when he walked through his fictional landscape past oppressed minorities and said he does not judge. Price and Folsom in Re-Scripting Walt Whitman explain how he was a was a nurse for both sides.

As if to underscore his own attempts to hold the Union together, to reconcile rather than punish, to help love triumph over revenge, he found himself particularly attracted to a 19- year-old Confederate soldier from Mississippi, who had had a leg amputated. Whitman visited him regularly in the battlefield hospital and then continued to visit him when the soldier was transferred to a Washington hospital. (82)

Whitman furthermore spoke about nursing a slave. Whitman would be willing to help someone fighting to protect slavery, and therefor intentionally or not, Whitman helped a racist, as well helping a slave. He was showing the universality of humanity in that he was trying to care for everyone, instead of caring for only the moral high ground. Whitman speaks about treating a runaway slave:

The runaway slave came to my house and stopped outside,

I heard his motions crackling the twigs of the woodpile,

Through the swung half-door of the kitchen I saw him limpsey and weak, And went where he sat on a log and led him in and assured him, And brought water and filled a tub for his sweated body and bruised feet, And gave him a room that entered from my own, and gave him some coarse clean clothes, And remember perfectly well his revolving eyes and his awkwardness, And remember putting plasters on the galls of his neck and ankles;

He staid with me a week before he was recuperated and passed north,

I had him sit next me at table … my fire-lock leaned in the corner. (Whitman 27)

But how effective is his affection, when he does not openly espouse that he disagrees with slavery? The Leviathan seems to have caught his tongue. He speaks of how the waves are like poems; he becomes the world itself. Embracing the world, for Whitman, means embracing a relationship with yourself and the world which is pantheistic; but that only goes so far. Later in Leaves of Grass, in the poem “Says,” Whitman will make a very short condemnation of slavery, but not an actionable theory, when he says, “I SAY where liberty draws not the blood out of, slavery, there slavery draws the blood out of liberty” (Leaves of Grass 1860 418). Whitman does not openly speak about having a political goal; but this paper has one. For all of Aristotle and Plato’s problems, they spoke of a mean in the Nichomachean Ethics and the Republic. It is like a bow and arrow that you pull and aim towards your goal. It involves a sort of teleology for both of them, a sort of view that the ends have forms, and that the forms conform to some sort of eternal pattern.

Will not the knowledge of it, then, have a great influence on life? Shall we not, like archers who have a mark to aim at, be more likely to hit upon what is right? (Aristotle 3)

Plato does not explicitly talk about the mean, but he does talk about moderation and selfcontrol as being between the extremes of passion and rationality. We can see how Plato reverses the Perlmanian theme of rationality being like a phallic force which operates in accordance with domination and the controlling of the body through machinery. Rather, it is not that either of them are dominant over the other, but rather what you’ll find is there are people who balance between the “appetitive” and “rational” soul:

Take a look at our city, and you’ll find one of these in it [the self-controlled or master of himself]. You’ll say that it is rightly called self-controlled, if indeed something in which the better rules the worse is properly called moderate and self-controlled. (Plato 106)

Does that which forbids in such cases come into play at all – as a result of rational calculation, while what drives and drags them to drink is a result of feelings and diseases. (…)

Hence it isn’t unreasonable for us to claim that they are two, and different from one another. We’ll call the part of the soul with which it calculates the rational part and the part which lusts, hungers, thirsts, and gets excited by other appetites the irrational appetitive part, companion of certain indulgences and pleasures. (115)

Plato had a hierarchy in his Republic. For him, the city is a mirror of the soul. Plato’s Republic upheld the “noble lie”: that there was gold, silver, and iron in people’s blood depending on what class they were in, like a caste system (91). Yet beyond rulers and hierarchy is anarchism, the idea that our rulers took power through brutal force and were never qualified to take power in the first place. So, we should organize society without rulers. One might liken queerness to the god Shiva the destroyer, a god that represents chaos – a productive quality which is not merely a vacuum, but a real which is productive and simultaneous with something akin to Brahma the creator. Shiva is a god of artists, – a productive force not representing any sort of male or female, but rather, as Bæden says, a single system (39), which operates simultaneously as territorializing and reterritorializing forces, as well as preserving forces, which miraculate into existence on the surface of the body without organs into coherent structures through the miraculating machine. This is also partial objects and flux, in general, and opposes the paranoiac machine, and miraculating machine, which make things appear as whole on the body without organs.

The body without organs is not God, quite the contrary. But the energy that sweeps through it is divine, when it attracts to itself the entire process of production and server as its miraculate, enchanted surface, inscribing it in each and everyone of its disjunctions. (Deleuze and Guattari 13)

We are of the opinion that what is ordinarily referred to as "primary repression" means precisely that: it is not a "countercathexis," but rather this repulsion of desiring- machines by the body without organs. This is the real meaning of the paranoiac machine: the desiring-machines attempt to break into the body without organs, and the body without organs repels them, since it experiences them as an over-all persecution apparatus. (9)

But the miraculating machine attracts the body without organs, and the paranoiac machine repels the body without organs in that the miraculating machine decodes the inscription on the body without organs, and synthesizes it into consciousness, and the paranoiac machine is based on paranoia and therefore is more conspiratorial.

Let us borrow the term "celibate machine" to designate this machine that succeeds the paranoiac machine and the miraculating machine, forming a new alliance between the desiring-machines and the body without organs so as to give birth to a new humanity or a glorious organism. (Deleuze and Guattari 17)

The subject spreads itself out along the entire circumference of the circle, the center of which has been abandoned by the ego. At the center is the desiring-machine, the celibate machine of the Eternal Return. (21)

A miraculating machine is akin to the Heideggerian present-to-hand in that an object is present and in your sight and you perceive it as a whole and made of a specific substance. In other words, beyond the language of religion, there is a productive, a destructive, and a preserving force in the world, as represented through the Hindu gods. Brahma represents a sort of universal consciousness, of which everything is a shape. But for Deleuze in Difference and Repetition, sense produces consciousness and its representations; consciousness and representations do not produce sense (145). This is the infinite multiplicity of the partial objects, a thousand tiny sexes for Deleuze and Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus (213), and, as Plato says in the Parmenides, the instant which is outside of time -

“And whenever being in motion, it comes to a rest, and whenever, being at rest, it changes to moving, it must itself presumably, be in no time at all?” – “Just so.” (163)

“So when does it change? For it does not change while it is at rest or in motion, or while it is in time.” – “Yes, you’re quite right.” (163)

- and allows for change to occur, or immemorial time, which is everything sense is, and produces, which is outside of time. This sense, outside of time is what Deleuze is describing as an “enmity” which does a violence on thought, which is what is conscious and in linear time, and thought responds in a violent way by producing identification in conscious experience:

An original violence inflicted upon thought, the claws of a strangeness or an enmity which alone would awaken thought from its natural stupor or eternal possibility: there is only involuntary thought, aroused but constrained within thought, and all the more absolutely necessary for being born, illegitimately or fortuitously into the world. (Deleuze 139)

This infinite multiplicity is more akin to the chaos and destruction of Shiva. The timeless chaos, which is everything that has already happened, happening again in the virtual, gives rise to the conscious; it is the machinic unconscious which Deleuze speaks about in Anti-Oedipus, and sense which Deleuze speaks about in Difference and Repetition is a sort of time immemorial (144); but for Deleuze nothing at all has a predecessor. Everything happening is infinitely different, and new every time. But this is not supposed to represent a sort of “progress” in a Hegelian or Perlmanian sense.

We can see how Perlman and Whitman both see a connection between the world and our own lives. This is a ready-to-hand connection in which the possibilities of the world are grasped and ordered by us, or in which we are ordered as technology and grasped as potentiality for another – you are the product being sold, in other words, when you go to the store. Your potentiality is to fuel money into the system as not only the customer, but as the transaction through which you pay for your subsistence in the system. Perlman looks at this system, and he feels repelled by it, and feels as though the correct response is to reject the system. But Whitman feels as though everything is just fine; he does not want to upset his careful peace brought to him by his belief in pantheism. Both Whitman and Perlman can offer us perspectives on how to be connected to the world and how to be authentic; for example, in sexuality in the sense of Whitman, and in living one’s life authentically outside of the machinery of the state for Perlman.

Perlman simply goes a step further than Whitman, in that Perlman takes an explicit stance against the thing that is causing the problem which Whitman does not name in his poetry. Whitman mentions the freedom of not being governed by officials, but he does not explicitly name the problem and talk about it as the point of what he is writing. Whitman might be exciting to liberal queer people, who do not care about emancipation for anyone but themselves, as well as people like Mother Earth’s writers (Internationalist 363), because he is emancipatory, but the emancipation that he offers is not actually a motivated one, or a directional one. Perlman points to the culprit and gives a detailed philosophical explanation for why you are controlled inauthentically, as machinery, by the Leviathan. Whitman can still be used as a refuge for fascism, capitalism, and colonialism; this is why Perlman goes beyond Whitman.

Perlman departs from Whitman in his critique of progress. Whitman is firmly rooted to his context in “Song of Myself;” along his walk through the landscape of frontier America, he describes lists of things which he becomes, like how he is with the man sleeping alone in the woods under his beard. “My face rubs to the hunter’s face when he lies down alone in his blanket” (1855 Edition 65). Progress for Fredy Perlman means uprooting from one’s context and moving forward towards an ever-further destination, eventually moving toward the speed of light and turning into a ball of smoke with no more mass, echoing Einstein’s relativity (Perlman 292). Whitman does not seem interested in uprooting his own context, although he says we should see through our own eyes, and not the eyes of the dead (22). Whitman cannot be seen as an anticolonialist or someone critical of technology such as Perlman. Whitman in his own time cannot speak to the time of Perlman, Heidegger, and Bæden. Perlman, unlike Whitman, has a negative view of technology. He views technology as a sort of phallic design (Perlman 173). Interestingly enough, he has a lot in common with Heidegger, who similarly felt that technology has the potential to be used to control people, and that people can be ordered as technology. There is a danger that everything is looked at as technology; but Heidegger says in “The Question Concerning Technology,” in Basic Writings, that people can never entirely become standing reserve:

The essential unfolding of technology threatens revealing, threatens it with the possibility that all revealing will be consumed in ordering and that everything will present itself only in the unconcealment of standing reserve. (339)

But enframing does not simply endanger man in his relationship to himself and to everything that is. As destining, it banishes man into the kind of revealing that is an ordering. Where this ordering holds sway, it drives out every possibility of revealing. Above all, enframing conceals that revealing which, in the sense of poeisis lets presence come forward into appearance. (333)

Yet precisely because man is challenged more originally than are the energies of nature, i.e., into the process of ordering, he is never transformed into mere standing reserve. (332)

Since people can never be completely transformed into standing reserve because they are challenged more originally than the energy of nature, Heidegger is saying, as he has been since Being and Time, that we can push back against the they and have authenticity. When one is caught up in the entanglement of oneself as Dasein with the inauthentic otherness of the they, one is closed off from the possibilities which one can project into the future. The times are not settled; facticity is the movement and turbulence in the they that mostly determines you: “Dasein’s facticity is such that as long as it is what it is, Dasein remains in the throw, and is sucked into the turbulence of the “they’s” inauthenticity” (223). Making a determination through one’s self, which is the instant of facticity and Dasein making determinations, as Dasein, and the circumspection of one’s possibilities with the past, present and future, projected onto the various possibilities that are presented to one based on their mood. Dasein projects outward ahead of itself its possibilities in Being and Time:

Being, ontologically. Being towards one’s ownmost potentiality-for-being means that in each case Dasein is already ahead of itself in its being. Dasein is already always ‘beyond itself’, not as a way of behaving towards other entities which it is not, but as Being towards the potentiality-for-Being which it is itself. This structure of Being, which belongs to the essential ‘is an issue’, we shall denote as Dasein’s “Being-ahead-of-itself.” (236)

The formally existential totality of Dasein’s ontological structural whole must therefore be grasped in the following structure: the Being of Dasein means ahead-of- itself-Being-already-in-(the-world) as Being-alongside (entities encountered in the world). This being fills in the signification of the term care, which is used in a purely ontologico-existential manner. From this signification every tendency of Being which one might have in mind ontically speaking such as worry or carefreeness, is ruled out. (237) This is the structure of care in Dasein; meaning you care about something and take an interest in grasping its possibilities. This is the structure in which being is an issue. Subjects are not welded together with objects like Hegel’s subject is substance. Dasein as primordially ahead of itself is whole - implying it is whole temporally, but not in a ready-to-hand way. One’s past and future are connected in facticity and projection.

The fact that this referential totality of the manifold relations of the “in-order-to’ has been bound up with that which is an issue for Dasein, does not signify that a ‘world’ of objects which is present-at-hand has been welded together with a subject. It is rather the phenomenal expression of the fact that the constitution of Dasein, whose totality is now brought out explicitly as ahead-of-itself-in-Being-already-in… is primordially a whole.” (Heidegger 236)

For example: you are hungry; the possibility of eating food becomes ready-to-hand as a possibility, phenomenologically. In other words, in order to be authentic, you need to make a determination which breaks with the they, as I might describe authenticity as the moment of the break with the socius; this break with the socius is outside of time in the aforementioned Platonic instant. One who is a child at play in a garden, like Shakespeare or Shelley, as Wilde describes those with individuality, lives with original thoughts, as he says most people:

Go through their lives in a sort of course comfort, like petted animals, without realizing they are probably thinking other people’s thoughts, living by other people’s standards, wearing practically what one might call secondhand clothes, and never being themselves for a single moment. (339)

Nonetheless, being authentic under the Leviathan is difficult when the flows of the machinery of the state intersect with the flows of your pivot points on the machinic and oppressive symbolic order. Heidegger’s aforementioned view of technology is as an ordering of the standing reserve (Heidegger 339). These are the bowels of the earth that are rended asunder by empire and capital, as Perlman describes.

The secret is out. Birds are free until people cage them. The Biosphere, Mother Earth herself, is free when she moistens herself, when she sprawls in the sun and lets her skin erupt with varicolored hair teeming with crawlers and fliers. She is not determined by anything beyond her own nature or being until another sphere of equal magnitude crashes into her, or until a cadaverous beast cuts into her skin and rends her bowels. (7)

As we possibly move towards our extinction, humanity has a choice. It can realize its radical subjectivity, its freedom, and it can throw off the fossil fuel industries, throw off the rapacious ruling class – the capitalist class. The billionaires, the landlords, the banks which let the rich hoard their money, the bosses. Let the workers be free, because we do not need rulers. Let the workers operate their own life. Queerness means rejecting masks and armors, rebelling openly against the colonizing forces that have afflicted our society within this patriarchal, white supremacist, fascist state, founded on colonialism and slavery. This state is known as the United States.

Whitman allows slave owners, before the Civil War began, to enjoy his poems uninhibited by a critique of whiteness, which means that his poems act in some way as a refuge of white supremacy. Whitman lets the Nazi come in and sit at the table with you, whereas the Nazi is not welcome at my table. Anarchism is not possible under a situation of anonymous Internet users, like every little private, depersonalized tyranny acting its force over you in an unregulated way; anarchism is about respecting personal autonomy and giving the maximum amount of autonomy to each person. Before talking about the United States, I will begin with the Nietzschean dilemma of how if you try to maximize autonomy, it creates a problem of a recurrence of hierarchy and violence. With going beyond anything, in the sense of a will to power overcoming the will to truth, there is always a sort of failure of the overman, the one who transcends values and goes beyond, is one is always resituated into a value schema. This is Nietzsche’s critique of the skeptic: they hold onto the will to truth just like the atheist in The Genealogy of Morals (108-9). But this is not about religion; this is about the concrete, material world, and the subsequent emancipation of queerness which is brought about by queerness. A queerness which Whitman in Leaves of Grass has when he says that he contains multitudes and contradictions (1855 Edition 67). The lighthouse in the distance is queer communism, the world spirit shining brightly.

The Nietzschean trouble with going beyond anything in terms of power dynamics.

The constructivist perspective is one which Deleuze and Heidegger differ on. As for Deleuze, he is a post-modernist, and in Difference and Repetition he views reality as a form of fiction writing (XX) - which is also real because he collapses fiction and reality - whereas Heidegger sees being as unconcealed and thinks that being produces our experiences. In Being and Time, Heidegger explains that being is not a particular being (194). The post-modernist interjection is a critical one, emerging from a Nietzschean perspective. In Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche subverts the scientific, foundation-based metaphysics and replaces it with the first post-modern ethics as such, an ethics which appears on the surface to be one of violence and war, but beneath it is one which subverts systematic thinking for one in which being is an empty fiction. The Will to Power comes at the heels of truth, as Nietzsche says about the opposition between the king and the one who wants to live in his castle, assumedly meaning that the will to power of the king contrasts with the emaciated and starving person who wishes to live on the king, as Nietzsche would put (226). Nietzsche seemed to put forward a master morality over a slave morality. So, the will to truth - slave morality in this case - would be what Nietzsche is critiquing. Nietzsche’s anti-systematic bodily underpinnings are similar to Freud's unconscious, and would be the basis of, ironically, the Zoroastrian religion as well, if we take the Zarathustra imagery as far back as Perlman does. And what does the will to power uphold if we go that far? The light of Ahura Mazda, which is the creation god in Zoroastrianism, and the even earlier primordial worship of the earth mother (Perlman 104-6). This life, which is free from mechanical capture, is the life which I see as the basis of a post-modern worldview.

The only question is to what extent are we already machines, and to what extent can we escape the machinic capture and pursue life. A machine is the cutting off of a flow; eating is machining. The social and mechanical are never separate from fantasy production. The social, historical, and mechanical collapse the possible and actual in the virtual, which is everything that has already happened happening again. This collapse of the social and mechanical in the virtual, and on the recording surface, means that the social world impacts people as the categories and roles that people adopt through a process which Deleuze and Guattari would call “reterritorialization.” The Deleuze and Guattari dictionary describes re-territorialization:

D (Special Combination): Absolute deterritorialization: Movements of destratification on the plane of consistency (or a re-territorialization on the plane), which emerge through relative deterritorializations (and result in reterritorializations on the plane through the inevitable new concepts, conceptual personae, people, or earth which populate it); an a- signifying semiotics which, due to its subjectivity, cannot be incorporated into a semiotic system. (Young, Genosko, Watson 310)

This is a word, for instance, but it is also a reflection on one’s own thoughts, and on enjoyment itself. One experiences social things at the same time as they experience capture. The capture into a social machine happens similarly to how Nietzsche describes in the Genealogy of Morals; one creates a painful memory, and this is like a debt that one pays to a creditor (45). Guilt and personal obligation have their origin in the relation between buyer and seller. In this relation, people “measured” themselves by another person. The creditor and debtor dialectic moves into the sphere of personal rights. Nietzsche describes how guilt before god becomes an instrument of torture, and the idees fixes (fixed idea) which is the painful memory god created (63).

Machinic capture is, simply put, a form of ressentiment. It is the belief, through the will to truth, in these systematic thoughts, and in being arranged by the masks and armors of tensions, by the flows of capitalism and societal expectations; it is a form of inauthenticity, the capture from the escape of immemorial time. Max Stirner goes beyond Nietzsche’s overman, which was an elitist thing, and made going beyond nihilism a matter of making something one’s property, and consuming it, producing it, or destroying it, through one’s might. Stirner, like Nietzsche, believed that there is a sort of continual war; for Stirner, might is the dominant force in the struggle in the end, as it is through one’s might that one continues to maintain their property:

Might is a fine thing, and useful for many purposes; for 'one goes further with a handful of might than with a bagful of right'. (Stirner 151)

He who has might has right; if you have not the former, neither have you the latter. Is this wisdom so hard to attain? Just look at the mighty and their doings! (172)

Only that which I cannot overpower still limits my might; and I of limited might am temporarily a limited I, not limited by the might outside me, but limited by my own still deficient might, by my own impotence. (189)

But ownness is something which everyone has who has the ability to grasp onto possibilities and express those desires as future outcomes in the world. This, the ability to consume, produce, destroy, or leave be, should not only be afforded to those who are strong, as one might interpret Nietzsche as saying. It should rather be afforded to everyone, giving to each according to their needs, taking from each according to their abilities. This individuality, this uniqueness, is something which is a direct expression of the will to power, an authentic expression of life.

In the univocity of multiplicity, desiring production produces lack, it produces consciousness, or the experience of psychoanalytic lack:

On the one hand, it [anti-production, the body without organs, which produces lack] alone is capable of realizing capitalism's supreme goal, which is to produce lack in the large aggregates, to introduce lack where there is always too much, by effecting the absorption of overabundant resources. (Deleuze and Guattari 235)

It is more of a matter of becoming captured for Deleuze: how the schizophrenic becomes tormented by Oedipus and the I which is imposed on them from society. We can see the life of Nietzsche here expressing itself in the bodily expression of Deleuze and Guattari. For them, philosophy is a bodily expression, one which is material and one in which one can become more or less captured in the triangulation of Oedipus, the family, the state, etc.

Partial objects unquestionably have a sufficient charge in and of themselves to blow up all of Oedipus and totally demolish its ridiculous claim to represent the unconscious, to triangulate the unconscious, to encompass the entire production of desire. (Deleuze and Guattari 44)

Partial objects are not representations of parental figures or of the basic patterns of family relations; they are parts of desiring-machines, having to do with a process and with relations of production that are both irreducible and prior to anything that may be made to conform to the Oedipal figure. (46)

Freedom in a Deleuzian sense is never abstract, and free from world historical events, but rather it sees all of these things as real, and a construct of desire which is produced by an infinite multiplicity: “The real is not impossible; on the contrary, within the real everything is possible, everything becomes possible” (Deleuze and Guattari 27). Perlman talks of the Leviathan speaking through people who are basically asleep, living attached to the corpse of civilization; Gnostics say that Archons encase the spirit in armor and put the people to sleep; Gnostics try to wake people from this sleep, if they can remember the primordial events that gave rise to the monster (Perlman 116). Deleuze is more subtle and doesn't give an example of what authenticity might entail. Rather, he shows us what being captured entails, and lines of flight from this capture. These ever more difficult lines of flight become trapped in a subjectum in “The Age of The World Picture,” in The Question of Technology and Other Essays: “the world becomes picture,” synonymous with representational scientific worldviews, at the same time “man’s becoming subjectum” (Heidegger 132) which, if it conforms to a world without any mythological significance, is one in which these escapes from machinic capture become only a machinic exercise in themselves. Here we can see a parallel between Heidegger and Perlman, in that both saw science and technology as something which was threatening to the authenticity of the person. But, as Heidegger points out, even those trapped in the subjectum are surrounded by the shadow of incalculability (135).