Hands Off Venezuela! Solidarity Spreads in Australia, SE Asia

The response to US attacks shows support for the Bolivarian Revolution remains among progressive movements in the region.

Progressive organizations led by Bagong Alyansang Makabayan along with the Philippines-Bolivarian Venezuela Friendship Association marched to the US embassy, denouncing the United States’ aggressive military attacks on Venezuela. Photo: Bulatlat

Following the Trump administration’s illegal attack on Venezuela, people’s movements and political figures throughout the world immediately mobilized in solidarity to reject the unilateral US military aggression. The mood of solidarity reached Southeast Asia and Australia, with public opposition and demonstrations in Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and elsewhere.

Progressive organizations led by Bagong Alyansang Makabayan along with the Philippines-Bolivarian Venezuela Friendship Association marched to the US embassy, denouncing the United States’ aggressive military attacks on Venezuela. Photo: Bulatlat

Following the Trump administration’s illegal attack on Venezuela, people’s movements and political figures throughout the world immediately mobilized in solidarity to reject the unilateral US military aggression. The mood of solidarity reached Southeast Asia and Australia, with public opposition and demonstrations in Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and elsewhere.

Nationwide emergency actions

Snap rallies in Australia were held on Sunday, January 4, in Melbourne and Sydney, with actions outside the US embassy in Canberra as well as in Brisbane and Hobart. The mobilizations were nationally coordinated by the new coalition Hands Off Venezuela, formed in October 2025 to organize emergency responses against the US military threats and airstrikes in the Caribbean.

Despite intimidation by the New South Wales (NSW) Police and an attempt to ban all public gatherings, up to 300 gathered at Sydney’s Town Hall in solidarity with the people of Venezuela. In Sydney, political economist Tim Anderson drew attention to the popular support for President Maduro and the Bolivarian Revolution.

Speaking about the people’s militia organized to defend their homeland from imperialist attack Anderson said, “there are many millions of poor people there, and they have guns, and they are not going to let the country be taken over so easily.”

Member of the branch executive of the Inner City Teachers Association (ICTA) of the NSW Teachers Federation, Dave Clarke, expressed solidarity with “the people of Venezuela during this horrific time of US invasion” and highlighted the long history of Australian teacher-union activism.

“Teachers are agents in the battle against material and moral erosion, against the scorching of human flesh and the searing of the human spirit,” Clarke told the rally. “We have work to do; building working-class power, becoming the masters of our own world, and ensuring our students grow up in a world free from war and imperial aggression”.

Several hundred protesters gathered on the steps of Flinders Street station in Melbourne on the same day with a lively march to Victorian parliament with chants of “the people united will never be defeated”, “hands off Venezuela” and placards demanding Albanese condemn the actions of the US and for the immediate release of the democratically-elected president of Venezuela.

Hands off Venezuela organizer Ria Evelyn emphasized to Peoples Dispatch, “the socialist government remains in power; the Bolivarian Revolution remains in process and millions of Venezuelan people are alert and united in the preparedness to defend their homeland and sovereignty.”

Red Spark‘s Max Lane addressed the Melbourne rally and urged attendees to get organized to build a sustained campaign against the Australian state and its imperialist policies and highlighted Trump’s claim that the US will take control of the Venezuelan government. “We hear this same refrain when Trump came up with his so-called ceasefire peace plan for Gaza: ‘we will run Gaza; we will run Venezuela’ … Behind it all is ‘we will run the world’, we should be clear about that,” Lane said.

“This is a period where the US wants to re-assert and maximize its control across the world. It actually needs to, because our civilization is decaying. Its economy is full of contradictions and more and more fragile. Without directly, in a colonial way, taking oil and other resources its economy will become more and more fragile. The US ruling class will become more and more desperate.”

In Perth, Western Australia (WA), the protest event was convened on the following day by Red Spark, in conjunction with the Communist Party of Australia and Socialist Alliance. Red Spark member Barry Healy told Peoples Dispatch that up to 200 occupied the forecourt of the building housing the US Consulate in the CBD.

There was a significant mainstream media presence. While being interviewed Healy said the demonstrators wanted “President Maduro of Venezuela to be returned to Venezuela immediately, and we want the Australian Government to take a strong stand about what’s going on.” “It’s absolutely outrageous that Australia should make milksop statements about what’s happening in Venezuela,” he continued.

WA Greens parliamentarian, Sophie McNeill also addressed the Perth rally. She argued that Australians “do not want to be complicit in the next illegal US aggression or genocidal campaign” and linked the struggle against US actions in Venezuela to stopping the AUKUS submarine deal here.

Snap rallies in Australia were held on Sunday, January 4, in Melbourne and Sydney, with actions outside the US embassy in Canberra as well as in Brisbane and Hobart. The mobilizations were nationally coordinated by the new coalition Hands Off Venezuela, formed in October 2025 to organize emergency responses against the US military threats and airstrikes in the Caribbean.

Despite intimidation by the New South Wales (NSW) Police and an attempt to ban all public gatherings, up to 300 gathered at Sydney’s Town Hall in solidarity with the people of Venezuela. In Sydney, political economist Tim Anderson drew attention to the popular support for President Maduro and the Bolivarian Revolution.

Speaking about the people’s militia organized to defend their homeland from imperialist attack Anderson said, “there are many millions of poor people there, and they have guns, and they are not going to let the country be taken over so easily.”

Member of the branch executive of the Inner City Teachers Association (ICTA) of the NSW Teachers Federation, Dave Clarke, expressed solidarity with “the people of Venezuela during this horrific time of US invasion” and highlighted the long history of Australian teacher-union activism.

“Teachers are agents in the battle against material and moral erosion, against the scorching of human flesh and the searing of the human spirit,” Clarke told the rally. “We have work to do; building working-class power, becoming the masters of our own world, and ensuring our students grow up in a world free from war and imperial aggression”.

Several hundred protesters gathered on the steps of Flinders Street station in Melbourne on the same day with a lively march to Victorian parliament with chants of “the people united will never be defeated”, “hands off Venezuela” and placards demanding Albanese condemn the actions of the US and for the immediate release of the democratically-elected president of Venezuela.

Hands off Venezuela organizer Ria Evelyn emphasized to Peoples Dispatch, “the socialist government remains in power; the Bolivarian Revolution remains in process and millions of Venezuelan people are alert and united in the preparedness to defend their homeland and sovereignty.”

Red Spark‘s Max Lane addressed the Melbourne rally and urged attendees to get organized to build a sustained campaign against the Australian state and its imperialist policies and highlighted Trump’s claim that the US will take control of the Venezuelan government. “We hear this same refrain when Trump came up with his so-called ceasefire peace plan for Gaza: ‘we will run Gaza; we will run Venezuela’ … Behind it all is ‘we will run the world’, we should be clear about that,” Lane said.

“This is a period where the US wants to re-assert and maximize its control across the world. It actually needs to, because our civilization is decaying. Its economy is full of contradictions and more and more fragile. Without directly, in a colonial way, taking oil and other resources its economy will become more and more fragile. The US ruling class will become more and more desperate.”

In Perth, Western Australia (WA), the protest event was convened on the following day by Red Spark, in conjunction with the Communist Party of Australia and Socialist Alliance. Red Spark member Barry Healy told Peoples Dispatch that up to 200 occupied the forecourt of the building housing the US Consulate in the CBD.

There was a significant mainstream media presence. While being interviewed Healy said the demonstrators wanted “President Maduro of Venezuela to be returned to Venezuela immediately, and we want the Australian Government to take a strong stand about what’s going on.” “It’s absolutely outrageous that Australia should make milksop statements about what’s happening in Venezuela,” he continued.

WA Greens parliamentarian, Sophie McNeill also addressed the Perth rally. She argued that Australians “do not want to be complicit in the next illegal US aggression or genocidal campaign” and linked the struggle against US actions in Venezuela to stopping the AUKUS submarine deal here.

Lawan agresi militer imperialist US! Palayain si Maduro!

The Indonesian left and progressive movement also condemned the Trump regime’s actions with hundreds joining a Hands Off Venezuela action on January 6 outside the US Embassy in Jakarta. Organized by the Labour Movement with the People (Gerakan Buruh Bersama Rakyat, GEBRAK) – a coalition of trade unions, student groups, NGOs and other progressive organizations – the Jakarta demonstration called for solidarity with the people of Venezuela.

In a press release, GEBRAK called for “solidarity of the working class and people worldwide” to “delegitimize this US imperialist aggression.” GEBRAK also highlighted the connections of imperialist militarism and women’s oppression. “Equally important, as part of the working class and people’s movement, we assert that imperialism, war, and blockades have deepened the oppression of women.”

“The US stranglehold has long exacerbated issues regarding access to food and healthcare, increased the burden of unpaid care work, and heightened risks of sexual violence, reproductive health damage, and structural impoverishment”.

Prior to the demonstration, various groups in Indonesia called out the US attack and expressed solidarity with the Bolivarian Revolution. The Militant Trade Union Federation in Indonesia (Federasi Serikat Buruh Militan, FSEBUMI) called on the international trade union movement to stand with Venezuela against imperialist aggression.

In a January 4 statement, the People’s Liberation Party (Partai Pembebasan Rakyat, PPR) said that Trump’s actions proved “that the US is the number one imperialist and number one terrorist.”

Reflecting on the history of US imperialist intervention in Indonesia, PPR’s statement noted “pretexts or fabricated reasons have always been used by imperialists to overthrow governments … we will never forget the pretext of ‘the assassination of a general’ as a narrative for the mass slaughter of communists and the ‘creeping coup’ against Sukarno in 1965”.

Immediately after the criminal attacks on Venezuela, left organizations in the Philippines also publicly opposed the Trump regime’s actions, with police dispersing a demonstration organized on January 5 by the Philippines-Bolivarian Venezuela Friendship Association, the New Patriotic Alliance (Bagong Alyansang Makabayan, BAYAN), and other groups outside the US embassy in Manila.

In a statement, the Labor Party in the Philippines (Partido Manggagawa, PM) condemned the US military attacks and kidnapping of President Maduro as “the larger plot of the United States to invade Venezuela to effect regime change, run the country, and retake control of Venezuelan oil”.

“History has shown – again and again – that imperialist-led regime-change operations elsewhere do not bring democracy or prosperity. They bring war, displacement, austerity, union repression, and the plunder of public wealth,” the statement read.

The Socialist Party (Partido Sosyalista, PS) called out the shameless reference to supposed narcotics trafficking, recalling the use of “fabricated narcotic conspiracies” by former President Rodrigo Duterte to attack political opponents and “justify mass murder and detention”.

Other Philippines left organizations including KILUSAN para sa Pambansang Demokrasya (KDP) and Alab Katipunan (AK) also released statements while in Malaysia a night of solidarity with Venezuela and against imperialist violence was organized by a coalition of civil society organizations and political parties to condemn the US military aggression against Venezuela.

“Remaining silent when facing tyranny is like blessing criminals. We call on all Malaysians from various walks of life who advocate peace and justice to join this protest action,” the coalition’s statement read.

Socialist Party of Malaysia (Parti Sosialis Malaysia, PSM) Deputy Chairperson S. Arutchelvan declared, “if the world remains silent today, no sovereign nation will be safe tomorrow … Either we unite to oppose this attack, or we will once again face neo-colonial domination.” It is likely that further actions will be organized in Australia and other parts of Southeast Asia, such as Timor Leste and Thailand.

The Indonesian left and progressive movement also condemned the Trump regime’s actions with hundreds joining a Hands Off Venezuela action on January 6 outside the US Embassy in Jakarta. Organized by the Labour Movement with the People (Gerakan Buruh Bersama Rakyat, GEBRAK) – a coalition of trade unions, student groups, NGOs and other progressive organizations – the Jakarta demonstration called for solidarity with the people of Venezuela.

In a press release, GEBRAK called for “solidarity of the working class and people worldwide” to “delegitimize this US imperialist aggression.” GEBRAK also highlighted the connections of imperialist militarism and women’s oppression. “Equally important, as part of the working class and people’s movement, we assert that imperialism, war, and blockades have deepened the oppression of women.”

“The US stranglehold has long exacerbated issues regarding access to food and healthcare, increased the burden of unpaid care work, and heightened risks of sexual violence, reproductive health damage, and structural impoverishment”.

Prior to the demonstration, various groups in Indonesia called out the US attack and expressed solidarity with the Bolivarian Revolution. The Militant Trade Union Federation in Indonesia (Federasi Serikat Buruh Militan, FSEBUMI) called on the international trade union movement to stand with Venezuela against imperialist aggression.

In a January 4 statement, the People’s Liberation Party (Partai Pembebasan Rakyat, PPR) said that Trump’s actions proved “that the US is the number one imperialist and number one terrorist.”

Reflecting on the history of US imperialist intervention in Indonesia, PPR’s statement noted “pretexts or fabricated reasons have always been used by imperialists to overthrow governments … we will never forget the pretext of ‘the assassination of a general’ as a narrative for the mass slaughter of communists and the ‘creeping coup’ against Sukarno in 1965”.

Immediately after the criminal attacks on Venezuela, left organizations in the Philippines also publicly opposed the Trump regime’s actions, with police dispersing a demonstration organized on January 5 by the Philippines-Bolivarian Venezuela Friendship Association, the New Patriotic Alliance (Bagong Alyansang Makabayan, BAYAN), and other groups outside the US embassy in Manila.

In a statement, the Labor Party in the Philippines (Partido Manggagawa, PM) condemned the US military attacks and kidnapping of President Maduro as “the larger plot of the United States to invade Venezuela to effect regime change, run the country, and retake control of Venezuelan oil”.

“History has shown – again and again – that imperialist-led regime-change operations elsewhere do not bring democracy or prosperity. They bring war, displacement, austerity, union repression, and the plunder of public wealth,” the statement read.

The Socialist Party (Partido Sosyalista, PS) called out the shameless reference to supposed narcotics trafficking, recalling the use of “fabricated narcotic conspiracies” by former President Rodrigo Duterte to attack political opponents and “justify mass murder and detention”.

Other Philippines left organizations including KILUSAN para sa Pambansang Demokrasya (KDP) and Alab Katipunan (AK) also released statements while in Malaysia a night of solidarity with Venezuela and against imperialist violence was organized by a coalition of civil society organizations and political parties to condemn the US military aggression against Venezuela.

“Remaining silent when facing tyranny is like blessing criminals. We call on all Malaysians from various walks of life who advocate peace and justice to join this protest action,” the coalition’s statement read.

Socialist Party of Malaysia (Parti Sosialis Malaysia, PSM) Deputy Chairperson S. Arutchelvan declared, “if the world remains silent today, no sovereign nation will be safe tomorrow … Either we unite to oppose this attack, or we will once again face neo-colonial domination.” It is likely that further actions will be organized in Australia and other parts of Southeast Asia, such as Timor Leste and Thailand.

Mainstream responses and challenges for the left

A handful of mainstream political parties and individuals in the region also publicly opposed the American regime’s actions. In the Philippines, Mamamayang Liberal (ML) Party-list lawmaker Leila de Lima criticized the attacks as violations of international law and the Australian Greens similarly highlighted the military aggression as a violation of international law (before baselessly describing it as providing “cover for a potential Chinese attack on Taiwan”).

People’s Justice and Prosperity Party (Partai Rakyat Adil Makmur, PRIMA) – part of the ruling coalition in Indonesia – issued a strong condemnation of the US attack and illegal kidnapping of President Maduro while perhaps the strongest statement from the political mainstream was by Prime Minister of Malaysia Anwar Ibrahim.

One of the only leaders to call for President Maduro’s release, Ibrahim wrote on Twitter that, “it is for the people of Venezuela to determine their own political future. As history has shown, abrupt changes in leadership brought about through external force will bring more harm than good.”

For the left, the task is to sustain and deepen networks for anti-imperialist action in the region, building international pressure against counter-revolution in Venezuela. This will include countering the mass disinformation campaign launched for decades against the government of Venezuela.

The response to US attacks shows support for the Bolivarian Revolution remains among progressive movements in the region, despite world imperialism’s offensive. The existing opposition among broader sections of the population against US military aggression can shift the balance of forces as the organized left grows stronger.

Nick Dobrijevich is an Asia Pacific solidarity activist, translator and researcher based in Sydney, Australia.

Courtesy: Peoples Dispatch

A handful of mainstream political parties and individuals in the region also publicly opposed the American regime’s actions. In the Philippines, Mamamayang Liberal (ML) Party-list lawmaker Leila de Lima criticized the attacks as violations of international law and the Australian Greens similarly highlighted the military aggression as a violation of international law (before baselessly describing it as providing “cover for a potential Chinese attack on Taiwan”).

People’s Justice and Prosperity Party (Partai Rakyat Adil Makmur, PRIMA) – part of the ruling coalition in Indonesia – issued a strong condemnation of the US attack and illegal kidnapping of President Maduro while perhaps the strongest statement from the political mainstream was by Prime Minister of Malaysia Anwar Ibrahim.

One of the only leaders to call for President Maduro’s release, Ibrahim wrote on Twitter that, “it is for the people of Venezuela to determine their own political future. As history has shown, abrupt changes in leadership brought about through external force will bring more harm than good.”

For the left, the task is to sustain and deepen networks for anti-imperialist action in the region, building international pressure against counter-revolution in Venezuela. This will include countering the mass disinformation campaign launched for decades against the government of Venezuela.

The response to US attacks shows support for the Bolivarian Revolution remains among progressive movements in the region, despite world imperialism’s offensive. The existing opposition among broader sections of the population against US military aggression can shift the balance of forces as the organized left grows stronger.

Nick Dobrijevich is an Asia Pacific solidarity activist, translator and researcher based in Sydney, Australia.

Courtesy: Peoples Dispatch

ExxonMobil CEO Tells Trump Venezuela Is “Uninvestable” Without Major Reforms

ExxonMobil has made clear that any return to Venezuela’s oil industry would require sweeping structural changes, despite renewed political interest in reviving the country’s vast but crippled petroleum sector.

Speaking at the White House alongside other oil and gas executives, ExxonMobil Chairman and CEO Darren Woods said Venezuela is currently “uninvestable” due to weak legal protections, restrictive hydrocarbon laws, and a history of asset seizures. Woods’ remarks were delivered during a meeting hosted by President Donald Trump focused on the future of Venezuela’s oil and gas industry and its implications for U.S. energy security.

Woods emphasized that ExxonMobil operates on a multi-decade investment horizon and cannot commit capital without durable legal and commercial frameworks. He noted that while Venezuela holds some of the world’s largest hydrocarbon resources, the challenge is not resource discovery but the ability to develop them under stable and predictable conditions.

Woods described the oil industry as a "depletion business for a product that is in great demand and will be in demand for many, many, many decades to come", underscoring why international oil companies remain interested in Venezuela despite its long-running political and economic crisis.

Despite that, ExxonMobil’s history in the country weighs heavily on its current stance. The company first entered Venezuela in the 1940s and has seen its assets expropriated twice, most recently during the nationalizations of the mid-2000s under former President Hugo Chávez. Woods said any third re-entry would require “significant changes” to avoid a repeat of past losses.

Those changes would need to include reforms to Venezuela’s hydrocarbon laws, credible investment protections, and a functioning legal system capable of enforcing contracts. Without them, Woods said, large-scale international investment is unlikely to return.

While ExxonMobil has not engaged directly with the Venezuelan government, Woods expressed confidence that the Trump administration could work with Caracas to help establish conditions more conducive to investment. He also stressed that the company does not yet have a view on whether it would be welcomed by the Venezuelan public or authorities.

In the near term, Woods said ExxonMobil would be willing to deploy a technical assessment team to Venezuela - if invited by the government and provided with adequate security - to evaluate the condition of oil fields, infrastructure, and production capacity after nearly two decades of underinvestment and operational decline.

He added that ExxonMobil’s integrated capabilities across production, refining, and trading could help bring Venezuelan crude back to international markets and secure market-based pricing, potentially easing the country’s severe financial strain.

Venezuela’s oil output has collapsed from more than 3 million barrels per day in the late 1990s to a fraction of that level today, reflecting mismanagement, sanctions, and the departure of international partners. The Trump administration has previously used sanctions as leverage to pressure Caracas while signaling conditional openness to oil sector engagement tied to political and economic reforms.

Woods concluded by thanking President Trump and senior administration officials for their focus on regional energy security, framing Venezuela’s potential recovery as both a commercial opportunity and a strategic issue.

For ExxonMobil, however, the message was unambiguous: without deep, durable reform, Venezuela’s oil riches will remain off-limits to one of the world’s largest energy producers.

By Charles Kennedy for Oilprice.com

ExxonMobil has made clear that any return to Venezuela’s oil industry would require sweeping structural changes, despite renewed political interest in reviving the country’s vast but crippled petroleum sector.

Speaking at the White House alongside other oil and gas executives, ExxonMobil Chairman and CEO Darren Woods said Venezuela is currently “uninvestable” due to weak legal protections, restrictive hydrocarbon laws, and a history of asset seizures. Woods’ remarks were delivered during a meeting hosted by President Donald Trump focused on the future of Venezuela’s oil and gas industry and its implications for U.S. energy security.

Woods emphasized that ExxonMobil operates on a multi-decade investment horizon and cannot commit capital without durable legal and commercial frameworks. He noted that while Venezuela holds some of the world’s largest hydrocarbon resources, the challenge is not resource discovery but the ability to develop them under stable and predictable conditions.

Woods described the oil industry as a "depletion business for a product that is in great demand and will be in demand for many, many, many decades to come", underscoring why international oil companies remain interested in Venezuela despite its long-running political and economic crisis.

Despite that, ExxonMobil’s history in the country weighs heavily on its current stance. The company first entered Venezuela in the 1940s and has seen its assets expropriated twice, most recently during the nationalizations of the mid-2000s under former President Hugo Chávez. Woods said any third re-entry would require “significant changes” to avoid a repeat of past losses.

Those changes would need to include reforms to Venezuela’s hydrocarbon laws, credible investment protections, and a functioning legal system capable of enforcing contracts. Without them, Woods said, large-scale international investment is unlikely to return.

While ExxonMobil has not engaged directly with the Venezuelan government, Woods expressed confidence that the Trump administration could work with Caracas to help establish conditions more conducive to investment. He also stressed that the company does not yet have a view on whether it would be welcomed by the Venezuelan public or authorities.

In the near term, Woods said ExxonMobil would be willing to deploy a technical assessment team to Venezuela - if invited by the government and provided with adequate security - to evaluate the condition of oil fields, infrastructure, and production capacity after nearly two decades of underinvestment and operational decline.

He added that ExxonMobil’s integrated capabilities across production, refining, and trading could help bring Venezuelan crude back to international markets and secure market-based pricing, potentially easing the country’s severe financial strain.

Venezuela’s oil output has collapsed from more than 3 million barrels per day in the late 1990s to a fraction of that level today, reflecting mismanagement, sanctions, and the departure of international partners. The Trump administration has previously used sanctions as leverage to pressure Caracas while signaling conditional openness to oil sector engagement tied to political and economic reforms.

Woods concluded by thanking President Trump and senior administration officials for their focus on regional energy security, framing Venezuela’s potential recovery as both a commercial opportunity and a strategic issue.

For ExxonMobil, however, the message was unambiguous: without deep, durable reform, Venezuela’s oil riches will remain off-limits to one of the world’s largest energy producers.

By Charles Kennedy for Oilprice.com

US Oil Majors Want Changes in Venezuelan Energy Laws Before Jumping In

Through a negotiated agreement between the White House and the newly-reformed government of Venezuela, the country's oil resources are now available to American companies for development and exploitation. But to get to actual investments in production, oil companies are going to need to see real changes on the ground before they start putting down money and shipping more barrels, according to supermajor ExxonMobil and many others.

Exxon has been producing oil in Venezuela since the 1940s, and it has gone through two rounds of asset appropriation - first in the 1970s, and again under former Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez in the 2000s. Caracas owes the company billions of dollars for nationalized infrastructure investments, Exxon believes, and repayment is nowhere in sight.

In this context, the company is reluctant to put in more money without better guarantees of a stable business climate. The firm tries to expand in countries where it is welcomed by society and can build a long-term relationship with its neighbors, over the decadal time horizons needed for profitable oil and gas extraction. These factors are not assured in Venezuela.

"If we look at the legal and commercial constructs—frameworks—in place today in Venezuela, today it’s uninvestable. And so significant changes have to be made to those commercial frameworks, the legal system, there has to be durable investment protections, and there has to be a change to the hydrocarbon laws in the country," said ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods in comments at the White House on Friday. "We haven’t talked to the Venezuelan government, and obviously we have yet to assess the people’s perspective with respect to ExxonMobil entering the country."

Among other hurdles, current Venezuelan law requires state oil company PDVSA to take a majority stake in any private development. This would preclude control over a project for international investors. In addition, PDVSA is not in a financial position to take a majority stake in multi-billion-dollar projects.

Beyond legal questions, analysts warn that Venezuela's political and security future is far from certain. There are multiple power centers inside the regime and the rest of the country - smuggling gangs in rural areas and borderlands, members of the military hierarchy, and armed militia groups - which could begin to pull the country apart in the event of a leadership breakdown or financial collapse.

"The entrenched challenges of migration, drug and other illicit trafficking, intensified substate violence, and perhaps de facto Balkanization of the country by various strongmen (and their domestic or foreign backers) remain palpable risks," wrote David L. Goldwyn and Andrea Clabough in a commentary for the Atlantic Council. "The Trump administration, focused on resource management in Venezuela, has so far shown little interest in resolving these issues. But they will not go away, and they could derail the administration’s vision for a more stable energy industry and country."

To provide an extra inducement to American oil companies to spend in Venezuela, the Trump administration may also look at making direct federal investments in Venezuelan oil production ventures. Asked whether the White House would support taking federal stakes in oil companies to stimulate business activity in Venezuela, U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright said that "that's certainly a very real possibility," speaking to Face the Nation. The acknowledgement is a departure from past policy: the administration has not previously proposed investing federal dollars directly in oil and gas production, within America or abroad.

The administration has already made arrangements for marketing Venezuela's existing oil production. It has contracted with trading houses Vitol and Trafigura to handle crude sales, and Vitol has already begun shipping U.S.-sourced cargoes of naphtha to Venezuela to aid production. The light distillate fraction is required to dilute Venezuela's extra-heavy crude for transport, and was previously supplied to PDVSA by Russia and Iran.

Top image: Hugo Londono / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Gold Reserve settles bank fees linked to PDV Holdings loan

Gold Reserve said on Friday it has agreed to pay about $5 million in commitment fees to banks tied to the loan facility it used to bid for shares of PDV Holdings, as part of its efforts to recover assets in Venezuela.

Separately, the company said it is reviewing and updating its security plans to support potential negotiations for a safe return to operations in Venezuela, following the ouster of President Nicolas Maduro.

Venezuela shock lifts gold, but mining revival remains elusive

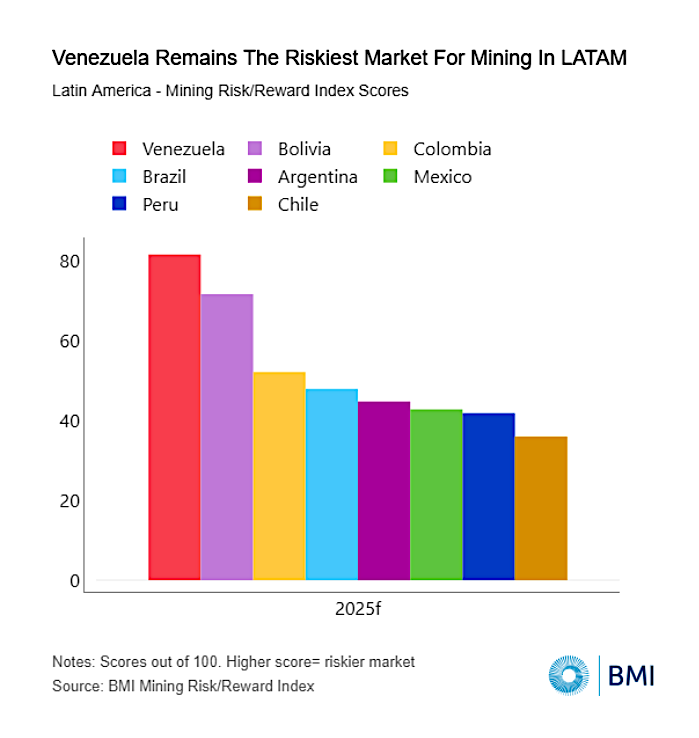

The Trump administration’s military intervention in Venezuela has jolted global markets, fuelling safe-haven demand for gold while doing little to improve the long-term outlook for the country’s battered mining sector, according to new analysis from BMI, a unit of Fitch Solutions.

Gold prices jumped 2.2% to $4,430/oz on January 5, following the US military raid over the January 3–4 weekend that led to the capture of President Nicolás Maduro. The move extended a powerful rally seen throughout 2025, when gold repeatedly hit record highs, peaking at $4,547/oz on December 26.

Prices averaged $3,450/oz last year, up 44% year-on-year, driven by heightened geopolitical risks, a more dovish Federal Reserve outlook and a weaker US dollar.

BMI says the removal of Maduro is likely to prolong geopolitical uncertainty, reinforcing the bullish case for gold into 2026.

The consultancy has already revised its 2026 gold price forecast to an annual average of $3,700/oz and highlights upside risks that could warrant further upgrades if global tensions persist.

Unlikely improvement

While markets have reacted swiftly, BMI sees little reason to expect a meaningful turnaround in Venezuela’s metals and mining sector, even under a post-Maduro government.

Over its 2026–2035 forecast period, BMI expects the industry to remain among the smallest and least attractive in Latin America.

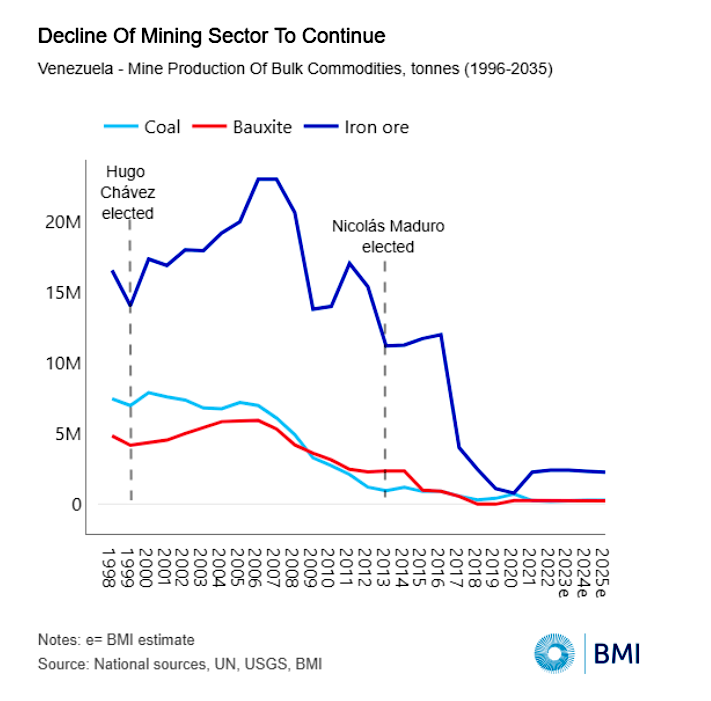

“Like its much larger oil and gas sector, Venezuela’s mining industry has suffered a steep decline over recent decades,” BMI said, pointing to widespread nationalization and chronic underinvestment.

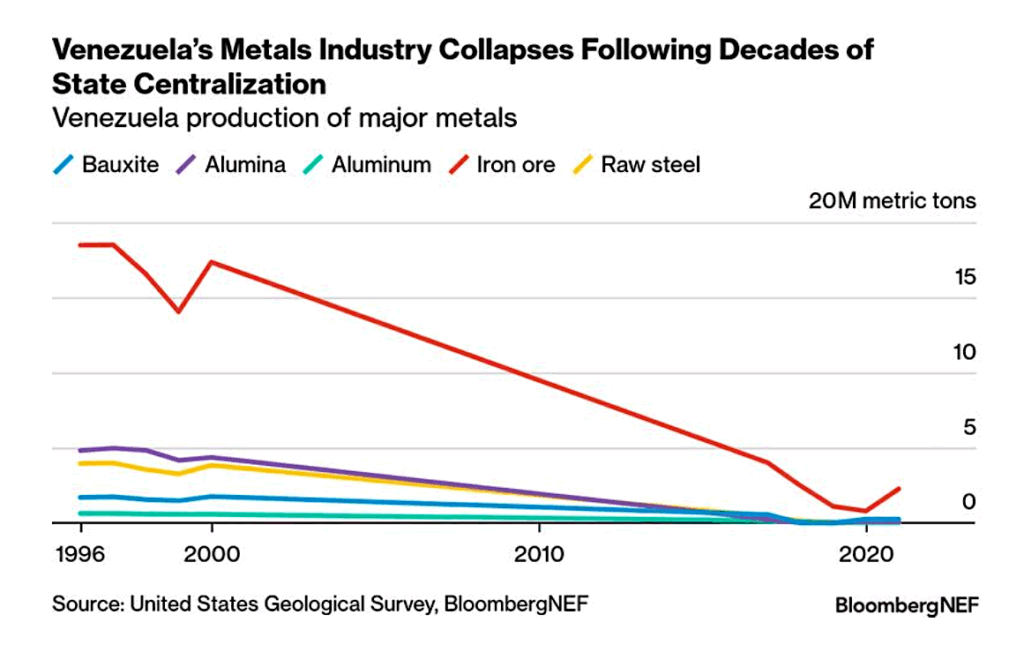

Twenty years ago, the country ranked as the world’s 12th-largest iron ore producer and eighth-largest producer of bauxite. Since then, output has collapsed.

Between 2004 and 2024, BMI estimates iron ore production fell from 20 million tonnes to 2 million tonnes, bauxite from 5 million tonnes to 0.3 million tonnes, and coal from about 6 million tonnes to less than 0.5 million tonnes. The consultancy does not expect these trends to reverse, citing degraded infrastructure and years of missed capital spending.

Gold mining is also severely underdeveloped, with operations in Bolívar and Amazonas often controlled by guerrilla groups and criminal gangs, deterring legitimate investment.

Long odds

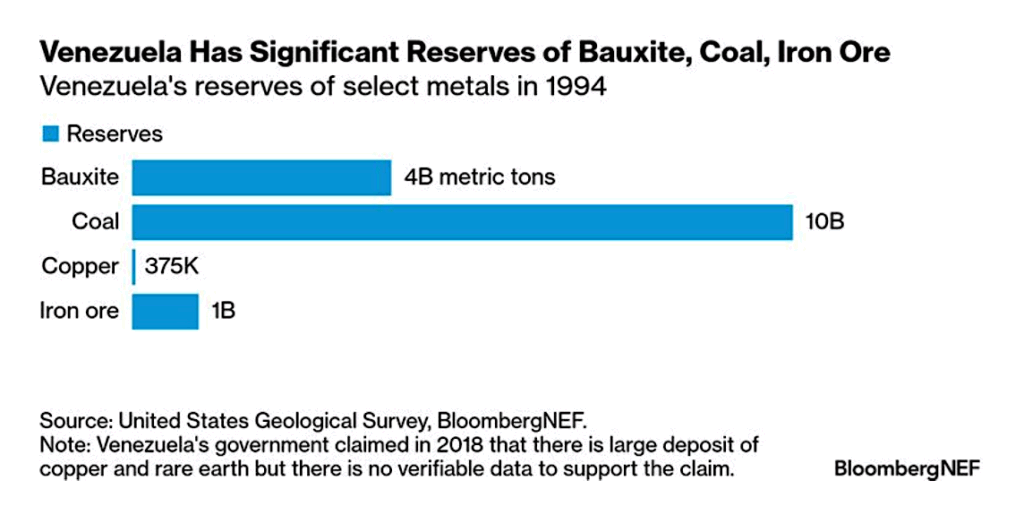

BMI argues that strategic and critical minerals represent the only plausible long-term opportunity for Venezuela’s mining sector. Government data suggests the Arco Minero del Orinoco hosts copper, nickel, coltan, titanium and tungsten — all minerals deemed critical to US national security.

A Washington-friendly government could pursue a Ukraine-style minerals agreement with the US, but BMI cautions that reliable geological data are virtually non-existent. Extensive exploration would be required before miners could commit capital, and Venezuela’s high-risk profile means only exceptional deposits would attract investment.

“Given the opaque nature of Venezuela’s official and black-market economy, we cannot say for sure what the real prospects are for critical mineral development,” Michael Cembalest, chairman of market and investment strategy for J.P. Morgan Asset & Wealth Management, said in a note this week. “But it’s notable that China, which controls the vast majority of critical mineral mining and processing activities around the world, is active in Venezuela.”

BloombergNEF echoes this scepticism, noting that metal production has declined by more than 90% over the past two decades. According to BNEF, reviving the sector would require a new transparent mining code, improved security and rule of law, major investment in infrastructure and at least a decade of sustained reform.

“The US government’s intervention has put Venezuela’s resources in the spotlight,” said Sung Choi, BNEF’s specialist in metals and mining. “But the country is crippled by poor geological data, low-skilled labour, organized crime, lack of investment and a volatile policy environment.”

Constraints for Venezuela’s mining sector “today are not geological,” Natixis analysts led by Benito Berber, said in a separate research note this week. “They are political risk, sanctions exposure, insecurity in mining regions, weak rule of law, and the absence of enforceable contracts. Until those fundamentals change, serious Western capital will likely remain on the sidelines.”

Ironically, Venezuela’s vast oil reserves may be the biggest barrier to mining investment. Oil projects are faster and cheaper to develop than mines, making them a higher priority for both companies and governments. As a result, experts say Venezuela is unlikely to become a meaningful player in global critical minerals markets anytime soon.

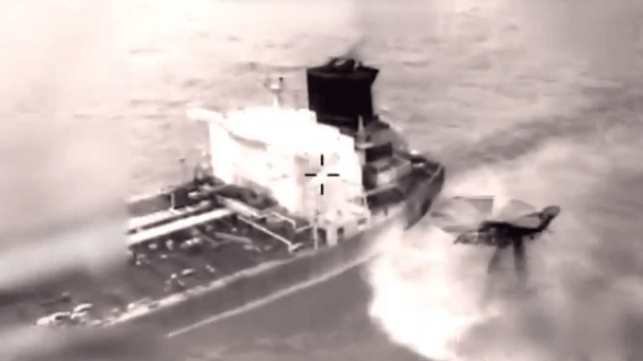

Venezuela Tanker Seizures Have Set a New Precedent, and More May Follow

The U.S. government has seized five shadow fleet tankers to date in its campaign to control Venezuela's energy exports, and it plans to market the seized oil on board. With the new government in Caracas agreeing to cooperate with U.S. authorities on the marketing and sale of the crude, there will likely be fewer need for at-sea seizures after the current roundup of a dozen-odd fugitive vessels has been completed. Four "escapee" vessels voluntarily returned to port in Venezuela over the weekend, reportedly after intervention by the new government in Caracas.

There may still be a use for the tanker-seizing tactic going forward: a quarantine would be a possible way to apply pressure to the government of Cuba, which has been communist-run since 1959 and is a prime target for the Trump administration. The White House has forbidden Venezuela (or other nations) to ship crude to Cuba; the decision is part of an attempt to force an economic slowdown on the island. Cuba does not have oil of its own, and needs to import about 35,000 barrels per day for vehicle fuel and power generation.

"There will be no more oil or money going to Cuba - zero!" President Donald Trump said on Sunday. "I strongly suggest they make a deal, before it is too late."

The prospect of more seizures raises practical questions of what to do with the tankers, some of which are reportedly in rough shape. The U.S. Coast Guard is getting ready to deal with an influx of battered shadow-fleet tonnage, according to the Washington Post. These VLCCs are not IACS classed or IUMI-insured, and many do not have a flag state at all. More inspectors have been called up to assess heavily dilapidated hulls. Some are "beyond substandard" in their condition, a Coast Guard memo seen by the Washington Post suggested. After temporary repairs and offloading, the ships could be auctioned.

To replace these aging tankers, America's maritime unions have called on the administration to make use of U.S.-crewed, U.S.-flagged tonnage to move Venezuelan oil. "To foster growth in the U.S.-flag fleet and boost the competitiveness of the American maritime industry, it is crucial that U.S.-flag carriers and their American crews have access to reliable, long-term cargo opportunities in the global trade landscape," wrote the AMO, MM&P and SIU in a joint letter. "Requiring U.S.-flag vessels, manned by American mariners, to transport Venezuelan crude oil legally and safely would uphold long-standing maritime principles and ensure that essential global energy supply chains function effectively."

In seizing stateless tankers on the high seas, the U.S. may also have set an example that others may follow. The government of the UK is considering comparable boarding actions for stateless vessels - but in this case, vessels that serve the Russian oil trade. Britain's Sanctions and Money Laundering Act of 2018 could provide the legal underpinnings of high-seas boardings, government sources told the BBC, though it would come with risk. With hybrid warfare in Europe at top of mind, UK-led tanker seizures could be a significant escalation in the ongoing grey-zone confrontation with Moscow.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

Op-Ed: U.S. Tanker Boardings Appear Consistent With International Law

Recent US boardings of oil tankers linked to Venezuela have prompted claims of piracy and illegality under international law. In reality, many of these boardings rest on a sound legal basis. Boarding vessels at sea is a routine naval activity permitted in limited circumstances under international law. This explainer outlines the international law governing maritime boardings and how it applies to the Venezuela cases.

Boarding operations on the high seas, beyond the 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone, are governed by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). While the US has not ratified UNCLOS because of domestic concerns over its deep seabed provisions, it recognizes the Convention as reflecting customary international law and complies with it.

Recent commentary has described US boardings as piracy, a term often used loosely. In law, piracy has a narrow definition under UNCLOS; it is limited to violent acts carried out for private ends by private vessels on the high seas. Whatever view one takes of the broader US campaign, these boardings do not meet the legal definition of piracy.

Under UNCLOS, primary legal authority over a vessel rests with its flag state, the country where the ship is registered, which is responsible for what occurs on board. There are, however, limited exceptions. Article 110 sets out five circumstances in which a warship from any state may board a foreign vessel on the high seas: where there are reasonable grounds to suspect the vessel is engaged in piracy, the slave trade, unauthorized broadcasting, is stateless, or is falsely claiming a nationality. These exceptions exist because piracy and slavery are treated as offenses of universal concern, allowing any state to intervene regardless of the vessel’s flag.

The question of statelessness is central to the recent US boardings. Under UNCLOS, any warship may board a vessel on the high seas if it is stateless, meaning it is not lawfully registered with any country or is falsely claiming a nationality. This is particularly relevant to shadow fleet vessels used to move sanctioned oil. They often operate outside normal maritime regulatory frameworks, including safety, insurance, and reporting requirements.

This appears to have been the case with several recent boardings linked to Venezuela. In one instance, a vessel falsely claimed it was Guyana-flagged. Where a vessel cannot demonstrate a genuine flag state, it may be treated as stateless and boarded under international law.

Another common feature of shadow fleet operations is the use of flags of convenience. In such cases, the flag state retains jurisdiction but in my experience will commonly authorize a boarding by another state’s warship, because they have no real connection with the vessel. This appears to have occurred in the boarding of the tanker Centuries on 20 December 2025, when the US intercepted the vessel with the authorization of Panama, its flag state.

A more complicated case study is the 7 January 2026 boarding of the vessel formerly known as Bella 1, now operating as Marinera in the Atlantic near Iceland, which was initially treated as stateless. When approached for boarding, the vessel refused consent and began crossing the Atlantic. During the transit, it painted a Russian flag on its hull and claimed to be registered as a Russian vessel.

This is precisely the scenario anticipated by the drafters of UNCLOS. Article 92 makes clear that a ship may not change its flag during a voyage except in cases of a genuine transfer of ownership or formal change of registry. Simply repainting a flag or asserting a new nationality mid-voyage has no legal effect. However, as technology has allowed for the registration of vessels online at sea, there is an open question about whether it was formally registered to Russia at the time of boarding. This is in many ways a new consideration for UNCLOS and may set a precedent. On the available information, when the vessel was boarded by the US on 7 January, that boarding was likely lawful under the international law of the sea, because it was not lawfully registered.

Other aspects of the US pressure campaign on Venezuela raise serious and legitimate questions under international law.

The tanker boardings, however, rest on a different international legal footing. Their lawfulness does not derive from unilateral US sanctions or from the existence of a blockade. The US has not established a lawful naval blockade, and what is occurring is better understood in legal terms as a form of quarantine, a distinction that warrants separate and more detailed discussion.

Instead, the boardings are grounded in the law of the sea itself. UNCLOS permits the boarding of stateless vessels and allows boardings with the consent of a vessel’s flag state where jurisdiction exists. Where applicable, US sanctions and arrest warrants may follow these actions as a matter of domestic law, but they do not themselves provide the international legal basis for the boardings.

The tanker boardings appear consistent with international law, although the Bella 1 episode and its attempted reflagging at sea will likely be debated by maritime lawyers for years to come.

Jennifer Parker is the principal and founder of Barrier Strategic Advisory. Having served over two decades in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) as a warfare officer, she holds a number of university and think tank affiliations, including as an Expert Associate at the National Security College, Australian National University and an Adjunct Fellow in naval studies at the University of New South Wales Canberra. Jennifer is also an International Fellow at the London based Council on Geostrategy.

This article appears courtesy of The Lowy Interpreter and may be found in its original form here.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

Guyana oil and mining sectors gain as Venezuela risk eases

Guyana’s mining and oil industries are drawing renewed investor interest as recent US military action in Venezuela reshapes regional risk perceptions and reduces uncertainty around offshore operations.

For years, Guyana’s economic rise has been overshadowed by a territorial dispute with Venezuela over the Essequibo region, a resource-rich area of nearly 160,000 square kilometres that Caracas claimed as its own and that includes offshore oil reserves.

Tensions escalated last year after Guyana backed a US military deployment in the Caribbean, following reports of gunfire from the Venezuelan coast near a vessel linked to Guyana’s general elections.

Venezuela’s defence minister accused Georgetown of encouraging a “war front,” while President Irfaan Ali said Guyana would support any action that removed threats to its sovereignty.

That backdrop has shifted since recent US military operations on Venezuelan territory led to the capture of Nicolás Maduro this past weekend.

Ali said stability, respect for the rule of law and a democratic transition were essential for Venezuela and the wider region, and confirmed talks this week with US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, citing Washington’s support for Guyana’s sovereignty and cooperation against transnational crime.

“The geopolitical risk associated with the regional environment could be reduced after the political change in Venezuela,” Angélica Méndez, a Guyana analyst at Control Risks, told Bloomberg Línea on Thursday, adding that a recurring source of uncertainty around offshore security, including Venezuelan military activity in Guyanese waters, had been removed.

Beyond oil

Oil has transformed Guyana since ExxonMobil (XOM) discovered major offshore reserves in 2015, but mining long predates the petroleum boom and remains central to the economy.

Gold, diamonds and bauxite, a raw material for producing aluminum, were being extracted commercially by the late 19th century, and bauxite production surged from the 1910s as foreign companies supplied aluminum markets during World War II and beyond.

After independence in 1966, bauxite assets were nationalized, then later reopened to foreign investment following privatization in the 1980s.

Today, gold is Guyana’s most important mineral export after oil and is produced largely by artisanal and small-scale miners, a sector formalized under the 1989 Mining Act and now a major source of employment.

Large-scale operators are also active. Zijin Mining runs Aurora mine, the only large-scale gold operation in the country. Other companies including Aris Mining (TSX. ARIS), G Mining Ventures (TSX: GMIN), Omai Gold Mines (TSXV: OMG) and G2 Goldfields (TSX: GTWO) are advancing projects across the interior.

Bauxite production continues under firms including BOSAI, the Bauxite Company of Guyana and First Bauxite Corporation.

Consultancy Control Risks said Guyana, despite lacking a formal sovereign credit rating, is viewed as a low- to medium-risk investment destination. Its main vulnerabilities lie in governance and institutional capacity rather than political or fiscal instability, a profile typical of small emerging economies.

The consultancy expects the outlook for oil and mining investment to remain positive, supported by President Ali’s pro-investment agenda, a planned auction of new offshore oil blocks this year and continued development of gas and energy transition projects.

Economic lift

Analyst Roberto Pérez told Bloomberg Línea that while global oil markets remain well supplied with moderate demand growth, broader geopolitical volatility poses a greater risk than price levels alone. Even with stable fuel prices, uncertainty around trade, diplomacy and energy policy could weigh on the global economy.

Guyana’s macroeconomic fundamentals, however, have strengthened sharply. World Bank data cited by Pérez show the loan risk premium averaged between 7.2% and 7.3% from 2020 to 2024, more than 350 basis points lower than in the previous five-year period. The IMF’s 2025 Article IV consultation noted that the country’s economic transformation continues to advance strongly.

Rapid growth in oil output, resilient mining activity and heavy public investment have pushed Guyana to the highest real GDP growth rate in the world. Growth in 2026 is projected at 22.4% by the World Bank and 24% by ECLAC. Non-oil GDP expanded by more than 13% in the first half of 2025, inflation hovered near 3% late in the year, and gross international reserves exceeded $1 billion in October 2025. The Natural Resource Fund held nearly $3.6 billion by September, equal to more than 12.5% of GDP.

“These factors explain the reduction in geopolitical risk and suggest Guyana’s fundamentals are strong enough to withstand current tensions between Venezuela and the US,” Pérez said.

(With files from Bloomberg)