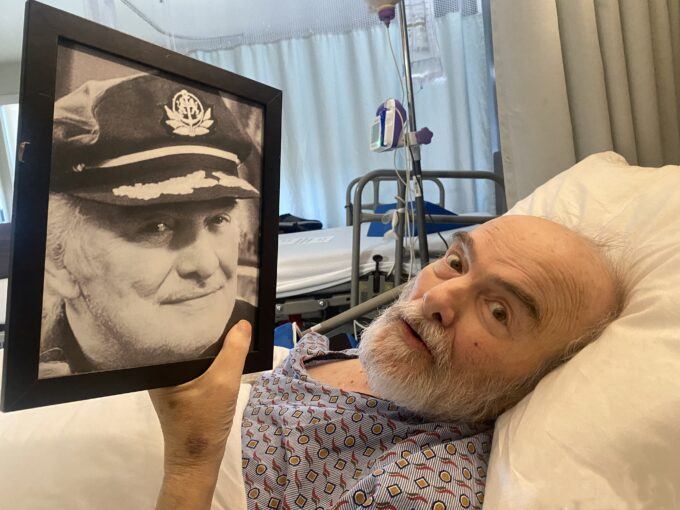

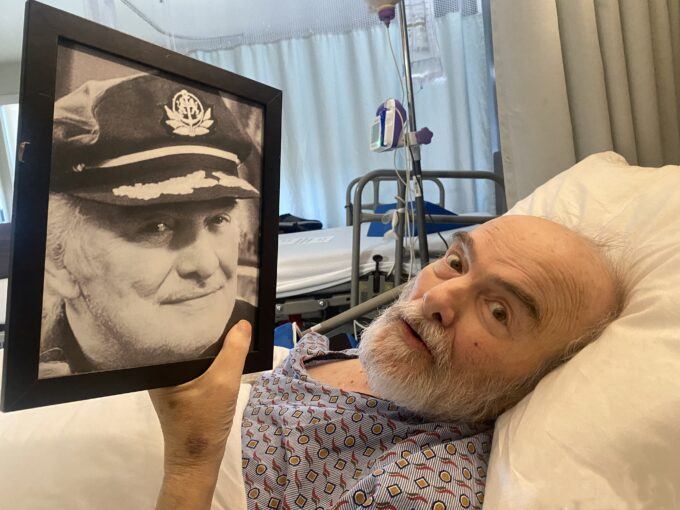

Cpt. Max. Photo courtesy of Susan Block.

Max is gone. My Great Love left his beautiful, long-suffering body on May 13, 2025 around noon PST, though I’m not sure of the exact time because I was crying too much to notice. Honestly, I am still crying too much to even write this, but I want to honor my darling Mickey now and forevermore.

And so, it is with deep love, sadness, reverence – and a dash of irreverence – that I announce the passing of Pr. Maximillian Rudolph Leblovic Lobkowicz di Filangieri, aka Captain Max, aka Mickey, aka David Rossi, aka Vivienne Hammer, aka MaxArtCore, aka Xam Paris, aka Max. Max was a truly great man, though never one to be impressed with greatness – his own or anyone else’s. So, irreverence is as vital as reverence for memorializing my darling Capt’n Max.

The Goal is the Journey

Max’s motto – drawn from Gurdjieff, Confucius and the vivid landscapes of his own travels – was “the goal is the journey.”

And what a journey it has been. Max led a remarkable life – over 81 years of romance, revolution, art, theater, publishing, radio, TV and internet broadcasting, erotica, pro-bonobo conservation, antiwar activism, international intrigue, fearless freedom-fighting, never-ending storytelling, loads of fun and endless love. Max wore many hats – in addition to having all those names – with panache, flexibility and a quirky originality that defied expectation.

As a producer, Max created thousands of fantastic, iconoclastic shows, salons, “speakeasies,” happenings and other events. As a publisher, Max pioneered the concept and practice of “reader-written magazines” long before blogs, or Tweets or TikToks. This was no easy task and led to many legal battles. But Max was a freedom fighter, as proud of his free speech arrests and prosecutions – most of which he won in court – as he was of his more conventional accolades.

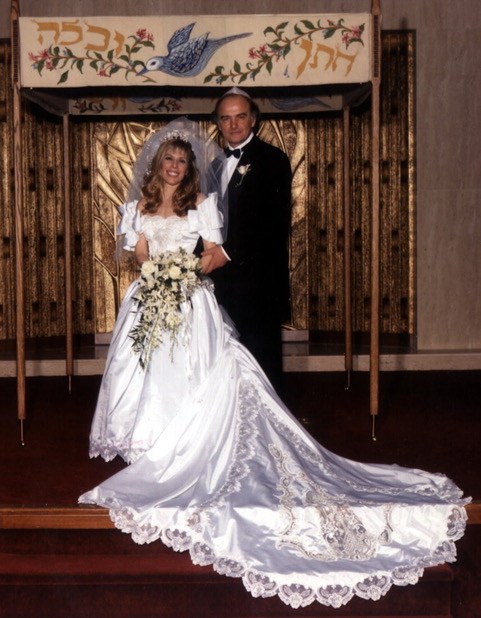

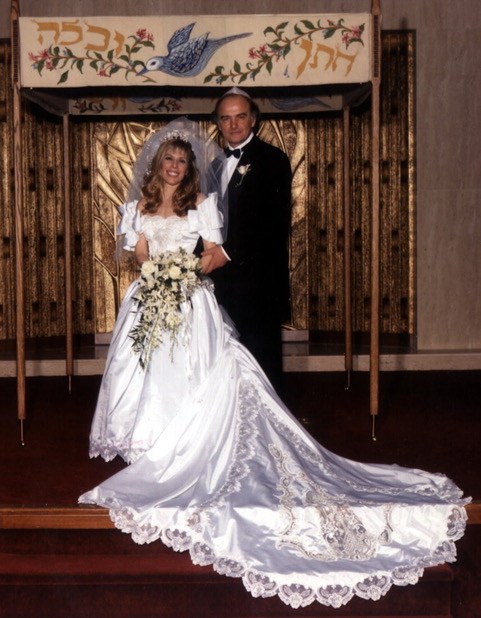

Max and I were married for over 33 years. Our partnership spanned more than four decades as friends, lovers, and creative collaborators, as well as husband and wife. Together, we produced legendary shows, best-selling books, bacchanalian gatherings, antiwar activism, sex-education, and peace initiatives rooted in our Bonobo Way philosophy. Our art galleries, bonobo conservation, sex therapy system and resilient romance spearheaded a pro-bonobo movement of peace through pleasure, mutual respect, enthusiastic consent, alternative lifestyles, communal ecstasy, equality, compassion, and free expression, helping to shape Underground Hollywood, the Downtown LA Art Scene, and the international conversation about peace and sexuality from the early 1990s through the 2020s.

Now he’s gone, and all I want to do is jump out the window and into his arms (good thing I’m on the ground floor). But I also need to tell his story.

Born in the “Pope’s Hospital”

Max was born on November 8, 1943 in Rome at Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù, aka ‘Child Jesus Pediatric Hospital,’ aka “The Vatican Hospital” or “The Pope’s Hospital,” right next to the Vatican and under the jurisdiction of the Holy See, during World War II as Allied bombs were dropping, even hitting the Vatican itself (despite its neutral status). So, Max entered the world in the shadow of destruction – and spent the next eight decades in the light of creation, liberation, connection, peaceful revolution, beauty and love.

Shortly after he was born, the infant Maximillian, aka Massimiliano, nicknamed Massimo, was whisked away from the war zone to Brescia in the Italian Alpine countryside, where he was raised by a princess, and painted by a nun. Yes, Max’s life began like a fairy tale – and in some ways, it remained one. I must confess, with Max, I often felt like I lived in a fairy tale.

The princess was his mother, Pr. Giovanella Filangieri, whose aristocratic forebears dated back to the 11thcentury. The nun was a member of the Franciscan Order of the Monastery of Santa Giulia (also known as San Salvatore) who captured little Massimo’s angelic features in an oil painting that now hangs on my wall of Max art. After the War, mother and child moved to Naples where they lived with Grandmother Pia Rossi Filangieri and other relatives who doted on little Massimo, pinched his cherubic cheeks and encouraged his artistic talents.

Like many fairy tale heroes, Max didn’t know his biological father, though he seems to have been a German officer, probably a Nazi. As a boy, he adored his Great Uncle Rodolpho, a Polish Jewish painter married to his grandmother’s sister (their father was Carlo Rossi Filangieri), his Great Aunt Anna Filangieri who was a ceramicist, and the two of them lived in a beach house filled with art.

Uncle Rodolpho had escaped from a Nazi concentration camp. He never made a fuss about it, but by example, he taught little Massimo that to survive and thrive, he would need more than his so-called “nobility”; he would have to use his wits, strength, character and artistic talent. Many members of the Filangieri family were involved in the arts, painting, sculpting, staging plays and other cultural events at the Filangieri castle in Naples.

At about age six, little Massimo’s life changed dramatically when his mother took him to a Neopolitan café to meet his stepfather, Prince Peter Francis Lobkowicz of Prague, Czechoslovakia. According to his recollection, this first meeting of father and son was punctuated with a hail of gunfire, at which point the little family of three, steeped in a long-gone aristocratic past, ran out of the café and into a brave new future.

Max’s ancestors on both his stepfather’s and mother’s sides can be traced to the Middle Ages. The House of Lobkowicz is a Bohemian noble family dating back to the 14th century, including his stepfather’s title, Prince of Prague, Duke of Melnick. Sponsors of great art, architecture and music, Lobkowicz nobility built several huge palaces that were confiscated by the Nazis and then the U.S.S.R., forcing most of the family into exile. Nowadays you can visit Lobkowicz Palace, the only privately owned building in the Prague Castle Complex, and immerse yourself in Bohemian history while sipping a Lobkowicz Beer, produced by Pivovary Lobkowiczbrewery, dating back to 1466.

On his mother’s Filangieri side, Max’s Italo-Norman ancestors date back to the Crusades, held many high military posts and built several fairytale castles and palaces. Antiwar Max often disparaged his war-fighting forebears. He was most proud of being directly descended from the prolific, progressive philosopher Gaetano Filangieri (22 August 1753 – 21 July 1788), 5th Prince of Satriano, whose writings influenced the American Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution, and who counted among his admirers the American statesman, Benjamin Franklin.

Coming to America

At the age of seven, Max, his mother, stepfather and his six-month-old infant brother, Charles Leblovic Lobkowicz, aka Charlie, set sail for America – in part to escape the gunfire, but also to continue the American/Filangieri connection – on The Italia. Crouched under its gigantic hull, sprayed by the briny sea, young Massimiliano fantasized about being the captain of a big ship like this one holding his family and other deposed royal “refugees,” leaving the Old World for the New. He never got that job (or even tried), but he did get the hat.

“Capt’n Max” was not an official “captain” in the military (he’d been vehemently antiwar since throwing down his own rifle during bootcamp when he realized he “could kill somebody”), nor was he even licensed to steer a canoe. He did like the captain’s hat – with “scrambled eggs” on the brim – as well as the big ships, bikinis and the endless ocean. Beyond all that, Max simply exuded the air of an authentic, strong but compassionate Man in Charge, a true Captain, so people called him that. He may not have piloted yachts, but he was the Captain of the Good Ship Bonoboville, aka the Ship of Fools for Love, and it’s inscribed inside my wedding ring, “Captain of My Heart.”

But it all started on October 4, 1951, as the Italia set sail from Naples to the Statue of Liberty, when Max discovered his love for the sea. Upon arrival, Massimo became Mickey, moving deep into the suburbs of Montclair, New Jersey, where his noble parents soon hired a housekeeper and butler to care for their two sons so they could go out to dinner almost every night. To make sure he grew up with the proper posture, the butler and housekeeper made Mickey eat his meals while holding books under his armpits, and if he dropped a book, he didn’t get dessert. Sounds draconian, but Mickey had the straightest back of anyone outside the guards at Buckingham Palace.

During these years, as befitting a fledging Prince of New Jersey, Mickey took horseback riding lessons. A natural equestrian, he won several prizes. But everything changed for him when his girlfriend at the time was killed falling off her horse during a jump. He continued riding, but stopped competing and never felt quite the same joy in the saddle again.

On June 10, 1955, 11-year-old Mickey had a mystical experience that would ripple through the rest of his life. As he sat under a large pine tree, toying with a pinecone, he found himself wondering who the love of his life might be. He felt he received a “sign” in the pines: The name of his future Great Love would be hidden within his own. Later, when he connected with me (born June 10, 1955), we both realized that the letters of my name, “Block,” appeared within his own, “Lobkowicz.” You might call that random, but for Mickey, it meant that the Pine Tree Prophecy had been fulfilled.

Later, when young Mickey was just beginning to explore his sexuality, amid the typical 1950’s lack of sex education, the housekeeper confronted him with a bunch of sticky, crumpled up papers she’d found in the bushes under his window. Mortified, he braced for a lecture. But instead, she just smiled and said, “Next time, use tissues – and throw them in the trash.”

Peyton Place, New Jersey

The Lobkowicz family of four all became naturalized American citizens in 1956, when Mickey was 12. Adjusting to American culture wasn’t easy, especially with limited English skills, but that wasn’t Mickey’s only problem. His deposed Czech Prince stepdad was an arms dealer, sometimes supplying both sides of a conflict and inevitably trouble followed. One day, when Prince Peter was out of town, a gang of gunmen came looking for him, then stormed the house. Later, Mickey surmised they were pro-Batista Cuban mobsters angry that Peter had sold better arms to Castro. They held the butler, housekeeper, Mickey and baby Charlie at gunpoint until wily Mickey could get a message to his school friends who rushed to the rescue, surrounding the house and pelting the intruders with rocks until they fled… at least, according to the tale that Mickey – then Max – liked to tell.

Fascinated by the secret lives of spouse-swapping Montclair adults – it all felt like something out of “Peyton Place” (the #1 bestseller at the time) – young Mickey found inspiration for his first publishing venture. He snuck into the Montclair Junior High School office after hours to mimeograph copies of his friend Bonnie Kelner’s localized “Peyton Place” parody, “Montclair Place.” It turned into the talk of the school – and got Mickey suspended. At least, he wasn’t deported. More importantly, it was then that he realized that publishing was his calling, and renegade publishing was his forte.

He also realized he liked Jewish girls, and he eventually married three (I was wife #3). He also converted to Judaism, guided by renowned “Renaissance Rabbi” Bill Kramer (Reform-Rabbinical guide to Elizabeth Taylor and Sammy Davis, Jr., among others), before marrying wife #1, Susan Spilka, whom he met in 1963, and with whom he had three children (Michael in 1968, Daniele in 1972 and Keri in 1982) before they divorced.

Speaking of divorce, Mickey learned that from his parents whose divorce upended his own young life. The split led Prince Peter to break the news to Mickey that he was his stepson, not his biological son, leading to a period of estrangement between the two. At the age of 15, Mickey moved with his mother to Genoa, Italy, where he acted in the State Theater Eleonora Duce of Italy and Teatro Arlecchino of Genoa. He was a natural performer on and off the stage. He also worked as road manager for English rock star Colin Hicks and performed rousing tributes to Jerry Lee Lewis and Elvis Presley during his time in Europe.

At 17 or so, he reconciled with his stepfather and moved to New York to live with him and his new wife Bibi, a stunning Brigitte Bardot lookalike with whom Mickey engaged in pillow fights. Sometime earlier (it’s not clear when), Mickey told the story of Peter sending him to a prostitute to “lose” his virginity. Poor over-excited Mickey climaxed before he even reached the lady’s door, and she was so kind and understanding, he became a lifelong, unashamed advocate for sex workers rights.

In the early 1960s, Mickey joined the U.S. Army at Fort Dix, New Jersey, but quit in bootcamp when he realized his new job involved killing people. For such insubordination, he was put in a military mental ward, but managed to avoid both electroshock therapy and a dishonorable discharge by threatening to blow the whistle on the Peyton Place-like, spouse-swapping society of his fellow patients and their doctors.

L.A. Star Publisher

After leaving the army, Mickey hitchhiked through the U.S.A. – waiting tables, digging ditches and taking other odd jobs along the way – until he eventually settled in Los Angeles. With his James Dean looks, Mickey was offered acting jobs, but the “casting couch” requirements made him uneasy; when one prominent casting agent’s hand went from the contract to Mickey’s thigh, he excused himself, crawled out the restroom window and decided not to pursue a Hollywood career.

So, he found work as a bill collector, the most thankless job in the world, but Mickey was good at it, good enough to start a family with his first wife. During this time, he also pursued his education at UCLA and Santa Monica City College and became increasingly active in politics. He supported Robert F. Kennedy, because he believed he would end America’s War on Vietnam and that he stood for equality and freedom. One pivotal moment for Mickey was attending a victory party at the Ambassador Hotel – a night marked by shock and horror, as RFK was assassinated there, a tragedy he never forgot and a huge blow to his political optimism.

Then the old publishing bug bit him again. Mickey met LA Star Publisher and Editor Paul Eberle and together they wrote the popular book, “Playing to Win: How to Deal with Bill Collectors.” Then in 1973, Mickey quit bill-collecting and started publishing The LA Star.

That brings up one of Max/Mickey’s other mottos, “It’s either Monarchy or Anarchy. What do you choose?” In quitting bill-collecting and taking up publishing, my Prince chose anarchy.

Power to the people!

One of Mickey’s first acts as publisher was to put a black and white photo of a topless hippie woman on the cover of The LA Star. She was a member of the Elysium nudist community in Topanga Canyon, written up in the paper’s lead interview with Elysium founder and director Ed Lange. Nevertheless, this was unprecedented, and copies of The LA Star – which also featured the early works of Hunter S. Thompson, Charles Bukowski and many esteemed renegade writers – flew off the racks, easily beating the competition (mainly The LA Free Press).

A series of arrests and lawsuits ensued, and Mickey, Paul and his wife and partner Shirley Eberle, won or settled all of them, usually represented by famed Free Speech attorney Stanley Fleischmann and eventually his office colleague, Barry Fisher. They changed the “rack laws,” paving the way for cable TV. Among their other legal wins was the landmark “Angie Dickenson Case” that overturned American Criminal Libel statutes in favor of Freedom of Speech. So, you might still be sued for putting Angie’s face on a naked body, as Mickey did on The LA Star, but you can’t go to jail for it.

“Reader-Written” Media Pioneer

During this time, Mickey entered into a lifelong friendship and artistic collaboration with Dutch multi-media artist Willem de Ridder, chairman of the FLUXUS art movement in Northern Europe and founder/publisher ofSUCK, the first European erotic magazine, featuring Germaine Greer, baring all in sex-positive, feminist prose and very explicit pictures.

Together, Mickey and Willem published some of the most innovative sex magazines and journals ever seen before – or since – including Love, Hate, Finger, God (called “G” on the cover because the religious printer refused to print it as “GOD”), Annie Sprinkle’s Hot Shit, The Sprinkle Report, Charles Gatewood’s “Forbidden Photographs,” The Ladies Room and Sound Finger (the first talking magazine), featuring the works of Marco Vassi, Annie Sprinkle, Veronica Vera, Alien creator Dan O’Bannon and many more, representing the most extensive documentation of human sexuality and erotic art in the 1970s. Certain issues cannot legally be possessed in the United States, and many are now sold as collector’s items for thousands of dollars each.

Mickey and Willem also “plundered” the European airwaves, producing “pirate” radio shows in San Felice, Italy, early audio experiments whose echoes can still be heard in contemporary productions, including our own FDR radio shows. Together, accompanied by their families, lovers, hippie *groupies* and Mickey’s big black poodle Robear, they trailblazed free speech as they traveled through Europe and America, making art, getting busted and publishing “reader-written” magazines that changed the world.

Yes, changed the world. Now, with social media, 90% of what most of us read is “reader-written,” but back in the Swinging ‘70s, it was unusual (if not blasphemous) to publish the prose, photos and art of readers – not professionals – with virtually no editing or censorship. This was a significant, if unheralded accomplishment for Mickey, Willem, Paul, Shirle, Susan, Annie, the Star Family and surrounding hippie groupies, as they were hounded on all sides – from Manson Family death threats (immortalized in the movie “Beverly Hills Cop”) to a string of LAPD busts and an Elmira, N.Y. home invasion during a formal dinner in which everyone – including the men – was dressed in lingerie.

Mickey’s work delved into some of the most mysterious yet widespread subjects in human sexuality behavior and fantasy. For this, he was prosecuted 22 times (or was it 23?), possibly making him the most prosecuted publisher in U.S. history. He usually won, but he served 18 months in Rhode Island’s Adult Correctional Institute where he ran for attorney general, and where his second daughter, Kari, was born while her mother, Mickey’s first wife Susan Leblovic, was shackled to her prison hospital bed. In 1982, so that Susan could be released to care for Kari and their other children, Mickey made a “deal” to plead guilty for the first time.

Paroled in 1984, Mickey returned to LA and soon began publishing again. He also started calling himself “Michael.” His new publishing ventures were much tamer, but also ground-breaking as “reader-written” media. Along with Ellen Dreksler (his second wife, with whom he had his fourth child, Jonathan Dreksler, in 1989), Brad Bucklin, Rudy Marinacci, Robert “The Bear” Wachtel, Kelly Bushinski, Tim Timmermans and others, Michael published “Meetings with Remarkable People” in 1986, “Beverly Hills, the Magazine” and, most famously, “The Brentwood Bla Bla” in 1987. In 1989, Michael sold both magazines to Eli Broad of Kaufman and Broad, but remained publisher. Then in 1990, they were sold to Robert Page of the Chicago Sun-Times who ruined the “reader-written media” concept – and soon completely destroyed both entire magazines – by inviting the advertisers to write the articles about their own businesses.

As soon as he saw his beloved magazines changed from reader-written to advertiser-driven, Michael quit.

Dr. Suzy and Cpt. Max. Photo courtesy of Susan Block.

Captain of My Heart

Circle back to late 1984: “Michael” (formerly Mickey, soon to become Max), was working for a short time as a dating service consultant when he met me, Susan Marilyn Block – soon to be “Dr. Suzy.” I drove to his office – “Captain of Her Heart” playing in my car – on a mission to close a sale for a commercial spot on my weekly KIEV radio show. “Michael” advised the service to buy the spot, and we began corresponding. I also started calling him “Max”—when I found out his real first name was “Maximillian,” and the name stuck. After all, it was his original princely name.

We fell in love – very slowly – seven years of friendship and creative collaboration that metamorphosed into a 33-year marriage – like a long jazz riff that flows into a symphony of lust with trust, and occasional long phone calls in which we agreed that greed was not the answer and war was not the way. I played his “Soap Salons” on my radio shows, and he published my opinion pieces in his magazines. Then, in 1990, Max’s second marriage ended, and he moved his personal effects into The Brentwood Bla Bla’s executive suite on the 11th floor of the Brentwood Plaza; that’s when we began to notice each other romantically.

But first, we collaborated on more audio art. In late 1990, we produced Desert Susan, crystallizing our mutual opposition to war in general and “Gulf War I” in particular, which was disturbingly popular at the time. A lyrical, hypnotic program featuring Sinéad O’Connor’s rendition of Prince’s “Nothing Compares to U,” antiwar poetry, “ethical hedonism,” and excerpts from Sun Tzu’s Art of War, cassettes of Desert Susan were sent free to thousands of troops and officers in Desert Shield and Desert Storm in 1990-1991. Over the years, Max and I heard back from many troops who had received these cassettes, turning them from war to peace. We also created the best-selling audio series, Bedtime Stories for Adults, including The Great Erotic Train Ride, Office Fantasies, and Passions of the Plaza, reflecting our own escalating passions for each other.

In 1991, Max moved out of The Brentwood Bla Bla executive apartment and into my West Hollywood condo, occasionally appearing on my show, then on KFOX radio, and getting me out of jams. When one of my guests, Doors’ drummer John Densmore, called me an hour before showtime to complain that the car I sent to pick him up was too small, Max asked a friend with a limo to pick up his Rock Royal Highness, and we had such a good show, “Hello, I Love You” became our theme song.

In 1992, Max started producing my broadcasts, now “The Dr. Susan Block Show” (having obtained my first Ph.D. in philosophy with a major in psychology), on radio and public access TV. He also assumed the position of “Max the Butler” to my “Mistress of the Airwaves,” fondly remembered by early fans of The Dr. Susan Block Show for his distinctive garb of white Captain’s hat, dress shirt and ultra-short cutoffs, plus his deeply soothing yet commanding baritone radio voice that announced the show and delivered his provocative commentary. Both Max and I used our Commedia dell’Arte experience to create memorable characters based on our real personalities, albeit theatricalized and eroticized. We called it Commedia Erotica.

Also, that year, Max the Butler served as campaign manager for my antiwar, antifascist, pro-free speech U.S. Presidential run. I didn’t win, but I did marry my Prince (Max) that same year.

On April 12, 1992, Max and I were wed at Har Zion Temple in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in a ceremony officiated by Rabbi Gerald Wolpe and Rabbi Ivan Caine. Guests flew in from around the world, including Max’s brother Charlie and Charlie’s daughter Giovanella from Milan, to witness the friendship that had blossomed into a passionate relationship and was now a lifelong commitment. Inside his wedding ring was inscribed “Master of My Soul,” and you already know what was inside mine.

Not everyone was happy to see Max and Suzy get married, of course; and though our attackers did not yet reveal themselves, they were sharpening their knives…

MaxCam on DrSuzy.Tv and HBO

Our lawfully-wedded, long-term love affair sparked our ongoing artistic partnership, producing The Dr. Susan Block Show, Dr. Block’s Journal (in print and online), BlockFilms Video Encyclopedia of Sex & Fetishes, The 10 Commandments of Pleasure, The Bonobo Way, Bonoboville, Dr. Suzy’s Speakeasy, four Real Sex segments, and two Radio Sex TV specials on HBO. Our HBO shows were directed by Emmy-award-winner Shari Cookson and executive-produced by Sheila Nevins who, in introducing us at an awards banquet, declared that despite her many Emmys and Oscars, she was most proud of her “pussy films.”

Max was the creator of the unique, critically acclaimed, slow-moving, closeup style of filming The Dr. Susan Block Show known as “MaxCam,” also featured on HBO’s Radio Sex TV. Sheila was so impressed with it, she ordered HBO’s camera quality to be “degraded” to look as close to MaxCam as possible when shooting Radio Sex TV. Thanks to MaxCam, a shrimp like me could look 10 feet tall.

After KFOX radio switched formats, Max and I expanded The Dr. Susan Block Show to over 150 stations nationwide through the Independent Broadcasters Network (IBN) – while also airing the video version of the show on public access TV stations in California and New York – broadcasting live from our bed (inspired by John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Honeymoon for Peace) in my West Hollywood condo.

When our engineers, assistants and guests started sleeping over – some of them never leaving – we realized we weren’t just a couple, but we weren’t a family either. We were a community. We expanded into a big Westwood penthouse overlooking the Playboy Mansion, where we first interviewed Gloria Allred, Nina Hartley, Lasse Braun, and filmed HBO’s Real Sex 11.

Then we moved into several suites at the old Century Wilshire Hotel, right down the street from Westwood Village Cemetery, where we visited Marilyn Monroe’s crypt for inspiration, as we continued to broadcast live on IBN nationwide, plus KMAX radio in LA. We also shot our two half-hour, #1 Nielsen-rated Radio Sex TV specials on HBO, Radio Sex TV with Dr. Susan Block and Radio Sex TV 2: Off the Dial, both in the inimitable MaxCam style.

A Police Raid, a Stabbing, More Shows and the Bonobo Way

Max and I experienced many great adventures during these groundbreaking shows and Felliniesque after-parties, almost all of which were peaceful. However, one night in 1994 at the Century Wilshire Hotel, an intruder armed with a military knife and packing ties – a jealous “cuckold” whose “hot wife” (with his expressed consent) had danced on our show with renowned director Lasse Braun – broke into our bedroom and hog-tied me while Max was across the hall in the edit bay. When Max walked in, I yelled, “He’s got a knife!” just as the guy lunged and managed to stab Max in the ribs, blood everywhere. But before the blade could cut deep, and only using his bare hands, Max pushed it – and the attacker – away from his body, then picked him up and threw him against the wall, where he fell with a thud and scurried out, soon apprehended by police. Later Max joked that he was aiming to throw the guy out the window, but missed. Though Max’s stab wound was superficial, the incision that the UCLA ER surgeon made to inspect the wound through his groin led to a hiatal hernia that bothered him the rest of his life.

Our philosophy of love, nonviolence (except for self-defense such as the aforementioned) and communitywas, in part, inspired by the bonobos, the “Make Love Not War” chimpanzees who are humanity’s closest genetic cousins and have never been seen killing each other in the wild or captivity. We first saw these amazing Great Apes in 1993 on the last episode of The Nature of Sex on PBS, and it soon became clear to us that bonobos practice the kind of sex-positivity, “peace through pleasure,” female empowerment, male nurturing, sharing, caring, and ecosexuality that we believed essential to keeping our own love alive – and even a key to world peace. The Bonobo Way became an integral part of our love and work together for the rest of Max’s life. “Bonobo Liberation Therapy” was also integrated into our sex therapy system, in private practice at The Dr. Susan Block Institute for the Erotic Arts & Sciences since 1991.

In 1995, Capt’n Max and I posted our first internet website on AOL, and it was promptly censored and deactivated for the use of the clinical sexological terms “masturbation” and “orgasm,” plus a photo of “copulating bonobos.” So, we started our own sites, DrSusanBlock.com and BlockBonoboFoundation.org. In 1996, Max produced my live in-depth radio and public access TV interview with Harvard Anthropologist and Demonic Males author Dr. Richard Wrangham about bonobo culture, the first in a series of interviews with more than a dozen bonobo ape experts over the next three decades.

That same year, Max and I interviewed Pin-Up Queen Bettie Page, “the dark Marilyn,” one of Max’s youthful crushes. It was the first live interview with the legendary, reclusive Bettie Page – and her longest live interview ever. When Max asked her to tell us what she told her fellow Tennessean, Senator Estes Kefauver (an old friend of his stepfather’s), in Senate sub-committee hearings when he asked what she thought of her bondage photos, she purred, “Why, Senator honey, I think they’re cute.”

Our interview with Bettie Page included a dazzling Bettie Page lookalike, an 18-year-old protégé of Max’s old friend Mistress Antoinette named Dita Von Teese. Dita would make several more appearances on the show – before, during and after her relationship with Marilyn Manson – on her way to becoming an international fetish and burlesque sensation.

Also in 1996, St. Martin’s Press published the first edition of The 10 Commandments of Pleasure: Erotic Keys to a Healthy Sexual Life, based on the philosophy of love, pleasure and The Bonobo Way that Max and I were developing – not to mention living. Published in over seven languages in more than a dozen countries, the book was a springboard to more Travels with Max, including our first trip to the San Diego Zoo to see the real bonobos, then New York, Philly, England, France, Italy, Germany, and Holland. While in Amsterdam, we met with Max’s old partner Willem de Ridder, artist Cora Emmons, singer Shai Shahar, The Happy Hooker author Xaviera Hollander and other members of the European erotic arts and sex-therapeutic wellness communities.

The Villa, Yale, a Real Speakeasy and another Police Raid

In 1997, we transported our merry band into the Villa Piacere, a four-story house in the Hollywood Hills surrounded by verdant foliage and noisy freeways. Continuing to film HBO specials and other sex educational documentaries, as well as broadcast our live weekly call-in shows, Max mentored emerging filmmakers in his distinctive MaxCam style while cultivating a vibrant space for me and the artists, technologists and therapists in our community to thrive.

Together, we crafted Dr. Suzy’s Speakeasy – a singular blend of talk show, revival, history lesson, antiwar rally, fetish forum, bacchanal, and bar – where guests could “speak easy” about topics that mainstream shows dared not broach. But no, we didn’t sell bootleg moonshine or any alcohol at all. The vibe was almost always peaceful—except for the one night when the LAPD raided the place. Ironically, it was during a big show featuring the artist Frank Moore, Heilman-C, KLOS personality Frank Naste and Free Speech Coalition lawyer Jeffrey Douglas, among others. There was even a UPN-TV news crew – thrilled to stumble into a dramatic police raid when all they’d come for was to film a live broadcast of the show. In the end, nothing illegal was happening, and no neighbors were bothered, so no charges were filed.

In 1998, Max and I presented Independent Prosecutor Kenneth W. Starr (using a Ken Starr lookalike that had everybody asking, “How’d you get Ken Starr to accept your award?”) the “Pornographer of the Year” award for his inquisition into U.S. President Bill Clinton’s pants. Not that we were fans of Bill Clinton‘s neoliberal policies or his draconian sanctioning of Iraq; we just felt that Starr’s “investigation” was a nakedly partisan power-grab dressed up in the pious trappings of a Moral Crusade. Moreover, Capt’n Max and I didn’t think anyone should lose their day job just for getting a consensual blowjob. HBO’s Sheila Nevins must have agreed with us because that was our one and only blatant political statement she didn’t make the editors cut.

In 1999, we learned that our cherished Villa Piacere was not actually owned by the guy to whom we were paying rent. So, off we went from the Hollywood Hills to Downtown LA, where we moved into a real Speakeasy – at least it had been one in the 1920s, still boasting the original bar – right across from the old Morrison Hotel (that predated the Doors). The high ceilings beautifully showcased our growing collection of great erotic artworks by Doug Johns, Karin Swildens, Dennis Dutzi, Annie Sprinkle, Betty Dodson, Yossi Vardan, John Evans, Robert Mapplethorpe, Scott Siedman and many more, including our own anti-Starr Report protest art, “The Hungry Republicans.” For Max and me, sharing erotic art was a political act. Dr. Suzy’s Speakeasy Gallery’s “Erotic Art of the Apocalypse” opening was enthusiastically reviewed by Stephen Lemons in LA New Times and filmed for Real Sex 25 on HBO.

Also in 1999, while attending Stage Blue, a Yale Dramat event, Max and I (Yale Class of 1977) met iconic Altadena artist Colonel Jirayr H. Zorthian (Yale Class of 1936) and his wife Dabney Zorthian. This sparked a great collaborative four-way friendship, and together, we produced several exhibitions of Jirayr’s master erotic artworks and made a film about his life, Zorthian: Art & Times, which we premiered at the Zorthian art memorial in 2005.

On January 22, 2000, we launched Eros Day – a holiday concept introduced to us by award-winning filmmaker Lasse Braun – to honor the Greek god of love, sex and life itself, coinciding with the planetoid Eros‘ closest approach to Earth. The celebration came together with divine erotic artistry, featuring Murrill Maglio as Eros and his wife Teri Weigel as Venus – the two making love on artist Mario Saucedo‘s giant wooden bondage cross – in the first of over a dozen classical and astronomical Eros Day celebrations, covered by rocket scientist Stan Kent, the LA Weekly and Citizen LA.

Also in 2000, the LAPD raided The Dr. Susan Block Show for a second time – when actress Ginger Lynn was our main guest. Again, no charges were filed. This time, Max and I sued the LAPD and eventually won a fairly large settlement on appeal, allowing us to rebuild Bonoboville and Dr. Suzy’s Speakeasy in the Soul of Downtown LA.

We moved to Flower Street near the new Staples Center, just in time for the Democratic Convention, for which we mounted an erotic art show called Democratic Sex, surreptitiously attended by many convention delegates who borrowed our whips and toys to act out their political frustrations on each other.

David Rossi & Xam Paris

Our life together was quirky but in many ways ideal. The problem was, as Max often said, “The ideal is the enemy of the real.” In early 2001, the morning after an all-night-long Eros Day Passion Play, Max was arrested by the LAPD on false charges, taken to Twin Towers jail and held there for two months before I could gather the $100,000 bail for his release. After several court appearances in June and July, 2001 that seriously threatened his life, Max disappeared, only to resurface in August, making the first of a series of calls to his befuddled prosecutor from various locations in France.

He also called me every day, including on 9/11 when, among other things, easy travel became history. Nevertheless, in October 2001, I reunited with Max – now going by the name David Rossi. I’ll never forget running from the taxi straight into my prince’s arms on a whistling, cheering, horn-honking street corner in Nice, France – like we were in a movie – and from there, we headed to Cannes, where we showed a movie, Weimar Love: Hot Sex in Pre-Nazi Berlin. Eerily prescient, Weimar Love forecast a “Reichstag-like incident” triggering a crackdown on civil liberties – echoing the aftermath of 9/11. This was the first of several trips I took to France to see David, combining our work (including my new Counterpunch columns which Max always read before I submitted) with great pleasure, deepening love, more antiwar activism and a dash of danger – now with a French accent. On April 12, 2002, we celebrated our 10th wedding anniversary in Paris.

We also celebrated our victory over the Rigas Family Censors of Adelphia Cable TV. Those were the days when you could face your censors directly, and possibly win. Helping our case was the fact that while the Rigases were censoring us for talking publicly about masturbation, they were privately masturbating their figures on their tax returns. They went to prison, and our show went back on the air uncensored (for a while), and my darling “David Rossi” took great joy in orchestrating that little victory lap from France.

In March 2003, in response to George W. Bush‘s bombing of Baghdad, David and I produced “Art Bombs: American Libertines for Peace“ at Il Teatro Café, featuring photographs, paintings, drawings and digital artworks by American artists that counteracted and commented on “Smart Bombs“ and the eroticization of explosive, corporate-sponsored violence. We also founded the Cannes Press Club, hosting press gatherings and a screening party for the 2002 premiere of Tom Wontner’s My Yacht, an independent film made at Cannes 2001. We parasailed, swam on nude beaches and cruised around Cannes harbor on the Adriasailing ship, doing our antiwar best to let whomever we encountered know that not all Americans were as bad as Dubya.

While I was in LA, David continued to perform his “Max the Butler” role on my weekly shows, his baritone booming to us remotely from France, sometimes with new friends like Imanne Sterning who adored her “Daddu,” with whom he broadcast shows on NSEO radio, an “American in Paris” speaking out against America’s wars. Imanne helped promote the French edition of The 10 Commandments of Pleasure, Les Dix Commandements du Plaisir (Presse Grancher).

In 2004, on a whim and a prayer, Max flew to Tijuana Airport, where my art curator Kim, handyman Tulsa and I picked him up and took him home to LA. Off the LAPD radar, he lived, loved and worked happily for several years under the names David Rossi and Xam Paris, producing bigger and more bacchanalian shows and railing against the NeoCons in our largest Speakeasy ever – a sprawling, 17,000-square-foot universe of art and exploration on Pico near the DTLA Fashion District. We invited guests from every corner of culture – professors, porn stars, politicians, poets – to discuss and celebrate eroticism as an art, the life force, a path to peace and a calling – our calling.

We also conducted seminars and events at Sex Week at Yale (my alma mater) in 2004, 2006 and 2008, and at Sex Week at Yale 2010, David spoke to a packed auditorium at the Yale Law School on the importance of Free Speech.

In 2005, award-winning filmmaker Canaan Brumley started making Speakeasy, a film about David, me and all the wild and colorful characters in attendance, as well as fictional characters played by actors Wallace Stevens and Sara Sioux Robertson. Many hope that one day, Speakeasy: The Movie will be released. In the meantime, “the goal is the journey,” and the journey of making Speakeasy was and always is extraordinary.

David and I also expanded our celebrations of conventional holidays in our own quirky “passion play” way – with parody, history, spectacle, sensuality, art, music and a lot of fun. We reenacted the story of Lupercalia (the original Valentine’s Day), put on wild Purimshpiels, Hot-Wax Hanukkah, Saturnalian Xmas, Dionysian Spring, Kinky Krampus, Easter Resurrections of Persephone, and Masked Balls for Halloween. We turned Labor Day into Labia Day and hosted great birthdays and wedding anniversaries that celebrated married romantic love and longevity with antiwar activism and communal ecstasy.

Also in 2005, David executive-produced “Dr. Suzy’s Squirt Salon: The Art & Science of Female Ejaculation,” which premiered at the Cinekink Film Festival, went viral and won a few awards. In 2008, our erotic antiwar music video “Blonde Island: An Island of Pleasure in a Sea of War” premiered at the Barcelona film festival and at Cinekink, which David and I attended in New York on our way to New Haven for another Sex Week at Yale.

Photo courtesy of Susan Block.

In Sickness & In Health

In May 2006, the night after Yale’s Whim ‘n’ Rhythm sang for a packed Speakeasy, I collapsed from septic shock. One minute I was writing my blog, the next I was in an ambulance. David had called the paramedics who saved my life, but my organs failed, I was in a coma for almost two weeks, and I came perilously close to death. David – Max – Mickey (despite his precarious “fugitive” status) was by my side in USC hospital every day. As I gradually woke up, struggling to breathe, there he was in his khaki vest and straw fedora, solicitously helping the nurses and doctors bring me back to life. Two months later, when he took me home in a wheelchair, he was my primary caregiver day and night.

As I recovered, we returned to hosting shows, and since everyone missed us, they were bigger and more bacchanalian than ever. Canaan continued filming Speakeasy through my recovery and beyond. Director Scott Webb also produced a series of Dr. Susan Block Shows, and various documentaries were made.

We also attended my 30th Yale reunion (Class of 1977), David proudly exchanging his captain’s hat for a “Yale Husband” cap – at least for the weekend. He loved his role as a Yale Husband, joining me at my 2017 and 2022 reunions and many other Eli events. Between reunions, several Yale students spent summers interning on The Dr. Susan Block Show – what a unique education they received!

Meanwhile, we expanded my telephone sex therapy practice to include therapists worldwide, all under David’s management. As calls for therapy, counseling and guidance came from near and far, and our little Institute grew into an international venture, occasionally, we’d get unwanted calls and scams. For those, David would often assume yet another identity, that of Vivienne Hammer, answering the phone in his typical deep baritone, but with a feminine lilt, “This is Vivienne Hammer, how may I help you?” confounding whatever scammer or bill collector was on the other end.

Then one day in May 2008, David opened the door, and a gang of police piled on top of him, taking him back to Twin Towers – this time with no bail. Though the original accusations had long been recanted, dropped and debunked, Max was now on the hook for “failure to appear,” a common charge for those who don’t bow to the system, even if they are innocent of the original charge. At least he was back to being Max again, his original name.

But now that they had Max, they didn’t want to let him out until they absolutely had to. So, from May 2008 through February 2009, I spoke on overpriced jailhouse phone lines every day and visited Max twice a week in Twin Towers, sometimes accompanied by Sara Sioux. During that time, Max continued to produce my shows by phone and through long visits, like when he reviewed our “Eros Day X Orgy for Obama” banners through the Twin Towers visitor glass, sparking lively conversations among guards and prisoners, many of whom protected Max because they were fans of his magazines, my shows or they just fell under the spell of Capt’n Max (even without the hat).

Capt’n Max Back at the Helm

In late February 2009, Canaan and Sara Sioux took me up to Delaney Prison to “spring” Max in an emotional reunion. With Capt’n Max back in my arms and at the helm of the Good Ship Bonoboville once again, The Dr. Susan Block Show took off – with great guests like Dave Bautista, Too $hort, Striperella artistAnthony Winn, Expedition Wild‘s Casey Anderson, bestselling author Robert Greene, artist Soma Snakeoil, lead singer Fat Mike of NoFX, actor John Barrymore, musician Elvis Schoenberg, bestselling Sex at Dawnauthor Dr. Christopher Ryan, Bonobo Handshake author Vanessa Woods, squirting star Annie Body, Hollywood socialite Amor Hilton, comedian Chris Gore and so many more for Eros Days, wedding anniversaries, bondage balls, musical concerts, stripper pole performances, erotic art exhibits and holiday bacchanals and intimate interviews.

One silver lining of Max’s time behind bars was that, after smoking since age 15, he quit cold turkey – and never touched a cigarette again. Still, he faced a variety of health setbacks. But it was nothing Capt’n Max couldn’t overcome – at least for a while – with me by his side. He was the Captain, I was the Admiral, and together, we kept the Good Ship Bonoboville sailing along. In 2009, Max underwent a quadruple bypass (which turned into a triple when one vein didn’t take). In 2011, he was diagnosed with bladder cancer, and in 2012, he underwent chemotherapy and neo-bladder surgery. Though the results weren’t perfect, he remained cancer-free for the rest of his life.

In August 2012, Max produced Big Win in Vegas, a film centered around a motorhome trip to see me receive my second Ph.D. – an honorary Doctorate of the Arts in Sexology from the Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Sexuality (IASHA) in a ceremony at the Erotic Heritage Museum in Las Vegas, officiated by Dr. Ted McIlvenna and attended by our friends and fans worldwide, followed by a wild party in the RV. Max was also the driver of that RV – our Bonoboville-On-Wheels.

We broadcast live from various locations, including the Hollywood Show, Zephyr Theater, Cupcake Theater,Adultcon and several years at Mistress Cyan‘s DomCon, giving talks on Bonobo BDSM and “The FemDoms of the Wild.” But our most sensational and intimate shows were at Dr. Suzy’s Speakeasy in the Soul of Downtown LA, all set in breathtaking bohemian environments designed by Max as Xam Paris. These were the glittering jewels in our crowns as king and queen of the DTLA underground erotic art scene.

From DTLA to Inglewood

Nothing lasts forever, certainly not glittering crowns. In 2013, as DTLA prices soared and the quality of life for artists declined, Capt’n Max and I relocated Bonoboville back to West LA, but this time in vibrant Inglewood, California. There, we flourished for five years of great shows, seminars, bacchanals, media and love – with only one cordial visit (not a raid) from the Inglewood police, which ended with us giving the officer-in-charge (who confided he and his wife were interested in swinging) an autographed copy of The 10 Commandments of Pleasure.

In 2014, Max published The Bonobo Way: The Evolution of Peace through Pleasure by me, for him. Everything we did was “by” and “for” the two of us anyway; we just hoped others might enjoy it too. The publication date was November 8, 2014 – Max’s birthday – and we held a big book launch with fire jugglers, dancers, Bonobo Way book-spankings, readings and other festivities. Our Bonobo Way book tour took us to UC Berkeley, UC Puerto Rico, UCLA, USC, Cal Tech, Yale, DomCon and AASECT (American Association of Sex Educators, Counselors and Therapists) and beyond.

In 2015, Max “discovered” powerful progressive newscaster/activist Abby Martin on Russian TV (RT), and invited her to Bonoboville as the only guest on a special edition of The Dr. Susan Block Show. Thus began a loving friendship and occasional media collaboration between Max, me, Abby, her husband Mike Prysner(also part of our 2022 Bonoboville Reunion), and Abby’s brother Robbie Martin that, among other things, encouraged us to open up and speak more freely about our growing support for Palestine.

In Inglewood, our mix of politics, sex, art and culture featured more colorful Commedia Erotica characters, including award-winning actor Luzer Twersky, Dominatrix and 2016 U.S. Presidential Candidate Tara Indiana, Aristrocrats comedian Paul Provenza, Ecosexuality author Dr. Serena Anderlini, actress Daniele Watts, gourmet vegan Chef Belive, rapper Ikkor the Wolf, Taboo actress Kay Parker, author Moushumi Ghose, comedienne Sally Mullins, artist Jeffrey Vallance and on and on. The sex made the politics more fun, and the politics made the sex more meaningful. Altogether, it made life good.

In 2019, when our Inglewood building was sold to members of the powerful Padilla family who expressed a profound interest in swinging, but doubled the rent, Capt’n Max moved us out to Arcadia, California. We set up our studios in a former Home for the Deaf that seemed perfect for us. We liked the bars on the walls because Capt’n Max was getting sea legs more often, and needed something to grab onto, we adored the big garden, our neighbors liked us, and our love and work flourished once again.

However, from the beginning, we were harassed by the City of Arcadia’s invasive inspectors and puritanical officials – despite our landlady’s continual support. This harassment seemed to coincide with rising social media censorship, including the deactivation of our YouTube and Meta accounts, and a broader decline in free speech, as the 2010s devolved into the 2020s, with waves of stifling and frightening repression coming at us from both the Right and the Left.

During the 2020 Covid pandemic, Max and I held a series of “Bedside Chats,” inspired by FDR’s “Fireside Chats” – except ours was from bed, zooming in guests like Hypatia Lee, Goddess Phoenix, author David Steinberg and fellow CounterPunch writer JoAnn Wypijewski.

Toward the end of 2020, we began co-hosting FDR (Fuck da Rich!) Radio, broadcasting live on several internet platforms. As usual, sex, politics and culture was on the menu, now served in the dining car of a train traveling through time into the great unknown, picking up guests and callers along the way. Max loved trains almost as much as ships. And then there were the limos and motorhomes. The goal was and still is the journey, after all.

In July, 2021, just as we were preparing for a podcast interview with Counterpunch founder Ken Silverstein about the City of Arcadia’s unconstitutional harassment, Bonoboville was raided by the Arcadia Police.

The cops, inspectors and a shifty-eyed City Attorney forced everyone out of the building, frisked us and made us wait outside while they searched Bonoboville. They found many interesting items – a giant painting of Marilyn Monroe topless and other erotic art, various computers, assorted sex toys, a lot of tapes, a few beds, lots of couches, many desks, multiple chairs, a couple guitars – but nothing the least-bit illegal. During our time waiting in the parking lot, Max – who explained to the police that he had a neo-bladder he couldn’t control – was denied access to the restroom.

Their warrant was unconstitutional, based on false information, and no charges were filed, but the City’s harassment continued. Max railed against this unconstitutional persecution, along with other signs of the then creeping (now galloping) fascism in American politics, in an interview with The LA Daily News and on all our FDR Radio shows. Was there a light at the end of the tunnel, or was our Love Train headed further into darkness?

In 2022, Vice TV produced a special in-person revival of The Dr. Susan Block Show and a “day in the life” of Capt’n Max and me. One of the funniest, most authentic moments ended with Max in front of the Bonoboville washing machine, explaining how we wash the dildos before shows, as he gleefully displays each soapy rubber schlong to the camera as if to say, “Relax, let’s have some fun.”

That April, 2022, we celebrated our 30th wedding anniversary; in May, we brought our “Make Kink Not War” movement to DomCom LA, and in June, we moderated a “Peace, Love and Bonobos“ roundtable at Yale. In 2023, on our 31st, Max took the wheel of the Bonoboville RV up the coast for a final spin, then spoke at Deep Throat’s 50th anniversary, enjoyed Abby Martin’s art show and saw our friends, the bonobos, also one last time. Then we celebrated Max’s 80th birthday with his son Jonathan, and our last big event was our 32nd Wedding Anniversary for a Free Palestine in April, 2024. Though by then, my great and vigorous Captain was confined to a wheelchair, battling an array of debilitating health issues, and a hint of wistful nostalgia was in the air, a feeling that this could be “the last time.”

A Life-Shattering Stroke

Then, it happened. On the morning of May 19, 2024, shortly after broadcasting his last live FDR show, Max suffered a major ischemic stroke. I woke up to his screams, called 911 and we rushed him to USC Hospital, where he was intubated and put on life support. The prognosis was dire, especially when the neurologists couldn’t remove a blood clot in his brain, his kidneys were failing precipitously, his heartbeat veering unpredictably, and he was unable to breathe on his own.

But Max fought for his life (I like to think he fought for our life), and within about a week, he was cautiously taken off the respirator. I rejoiced to see him look at me with what seemed like recognition. I squeezed his left hand, and he squeezed back. Still, the stroke had rendered my big strong darling almost immobile, virtually paralyzing the entire right side of his body, and splintering his mind. He couldn’t lift his head, eat or drink and had to be fed through a tube, first in his nose, then a G-tube and eventually a GJ-tube in his stomach.

Most frustrating, the stroke stole Max’s words. Afflicted with “aphasia,” he was trapped inside his own shattered thoughts and feelings, and when he tried to speak, what came out was jumbled, twisted, often nonsense. This would be devastating for anyone, but was especially painful for a publisher, public speaker and radio host like Max, with such a powerful, creative mind – now broken like a jigsaw puzzle spilled all over a wet floor.

It was heart-wrenching to see Max wrestle with simple phrases that used to flow so easily from his silver tongue. Though sometimes the struggle exploded into an aria of laughter, wild sound poems, funny faces or both, enchanting the nurses, therapists and even the most robotic of doctors. I tried to complement Max’s natural charm by supporting these often overworked, underpaid health professionals upon whom my darling husband’s life now depended, and I showed the really interested ones some of the many magazines he published and a few of our shows (the PG ones). Despite the inherent and sometimes deadly failings of the American Medical System (which I could complain about and have), most medical personnel treated Max like the VIP he was. And yes, we had good times – even some great times – in his horrible final year.

Aphasia was always in the way, breaking Max’s thoughts into gibberish, but every so often, he blurted out something special or delivered carefully pronounced but utterly scrambled instructions with the gravity of a Mafia don. I called it “Maxolalia” in the spirit of “Glossolalia,” speaking in tongues – like when, in a rush of babble, Max suddenly and very clearly declared, “We Are An Art,” or “I feel my brain,” “It’s not ending,” “There’s the insurance issue” and “We’re in the skin.”

I was not even sure he always knew who I was – he’d certainly forgotten our immense history together – though I know he knew I was *his* and he was mine. One late night in the ER, after we’d been separated for a few hours of tests, they wheeled him back in and he grinned at me through a morass of mucous and oxygen tubes, exclaiming, “My Girl is here!”

And I was. I was always there. Because Max taught me that real partnership means loving someone at their weakest, not just their strongest – even when others attack you for it, even when your President says “maybe you should just let him die.” It means doing what it takes to be a good Admiral when your Captain is wounded. It means finding beauty even in brokenness that can’t be fixed. It means giving your all to love, even when you get nothing back – besides more love… which is a lot.

And it means saying goodbye when you’re not ready (I’m still SO not ready).

Pleasure Therapy Painkillers

Though not a medical doctor or nurse, I was Max’s primary caregiver, so I wound up guiding him through life on the edge of death across three hospitals, four rehabs, over 10 ambulance rides and a nursing home – all in a little less than a year.

Though the aphasia made even the simplest communications confusing, the one language Max and I still understood was the language of love. A lifelong advocate for pleasure as vital to well-being, Max and I found ways to integrate pleasure therapy into his pain management.

Sure, we couldn’t have *sex* (aka intercourse), but our hands could dance together – “Hand-Dancing with the Stars” – and our lips could brush against each other, and we could make each other smile. I could massage and stretch his flaccid right arm while his strong left hand touched and twirled my hair as if it had mystical healing powers, and maybe it did.

Pleasure was Max’s most effective painkiller, and even some of the doctors agreed that the oxytocin of love worked better than Oxycontin the drug. And it wasn’t only romantic love. The joy, laughter and wonder he shared with friends, family, colleagues, the Bonoboville crew and Chico the Bonoboville dog – those who braved hospital, rehab and nursing home visits – as well as the doctors, nurses and therapists who cared for him within the punishing limits of insurance constraints, all helped to kill Max’s constant excruciating pain.

Another way around aphasia was through music. Having brought Max continuous joy throughout his life, in his final months, music was now a life raft through the post-stroke sea of pain and confusion in which Max found himself swimming. He especially loved singing his own little tunes – to communicate, to entertain, to remind us that he was human, to ease his own agony and to give himself courage. He even sang sometimes during his most agonizingly painful procedures and treatments like “wound care.”

“No other patients ever sang during wound care besides Max,” confirmed his treatment nurses when I inquired. For that alone, Max will never be forgotten in these halls of great sickness and healing.

Throughout this “Year of Living Precariously,” Max’s health went up and down like a damn yo-yo, but each time it went down, it dropped a little lower. After the stroke, he never really got “better.” Sometimes, he’d rally – such as for his old friend Barry Fisher’s “Bella Ciao” accordion concert that got the nurses and other patients dancing around Max’s bed, or for special physicians that really went the extra mile for him like Kaiser’s Armen Aghabegian, and for our luminous amethyst 33rd wedding anniversary on April 12, 2025. Some couples ride to their anniversary celebration in a limo; we took an ambulance, laughing, singing and loving all the way to Max’s room at the South Pasadena Care Center (SPCC), where we were soon surrounded by friends – both human and canine – balloons and flowers.

Max loved flowers, especially roses – right up until the end. Their fragrance seemed to revive him, if only for a moment of what seemed – from the look in his big hazel eyes – like the purest pleasure in the world.

Photo courtesy of Susan Block.

Farewell Capt’n Max

Max was an astoundingly strong, vibrant, creative, passionate, Zorba-like, Commedia-style character, as well as the most loving and romantic husband I could dream of, and a very peaceful, kind, caring, sharing bonobo sapien. But he was also a force of nature, always creating, publishing, producing, performing, pioneering and steering the ship, supporting and mentoring others, making you think or laugh or maybe making you mad – a larger-than-life lover of life.

But no matter how lively you are, a major ischemic stroke takes you – body, shattered brain and soul – to as deathly a place as you can go in life – short of death itself. In Max’s case, death came for him in May of 2025, a few days shy of the first anniversary of his stroke, and he was rushed from SPCC to the ER and then ICU of Huntington Hospital (the Pasadena branch of Cedars Sinai) with dropping blood pressure, kidney failure and low oxygenation, a kind of sepsis like I had had, but worse. He rallied in the ICU, but then the yo-yo dropped down, way down, hitting bottom, and his heart failed. In the last moments of his life, just before noon on May 13, 2025, my darling Max squeezed my hand hard – maybe to say “good-bye” – and then he was gone. The whole ICU crew came in to try to revive him, but despite heroic attempts, he would not return. Capt’n Max had set sail.

I’m no necrophiliac, but I kissed, hugged, wept and wailed over his still beautiful, but oh-so-ravaged body until it grew cold and hard as an ice sculpture, and the morgue technicians took him away. Naively, I asked if I could go with him, and gently as they could, they refused.

On Monday 6/9/2025 (Max would love that date – 6/9 – a “69 Date”), Max was cremated, as was his wish, by Pierce Brothers Mortuary, starting with a private “visitation” at the Westwood Village Cemetery – the one we used to visit when we were lived at the Century Wilshire Hotel – followed by a procession around the grounds. Many Old Hollywood stars are entombed on those grounds, and Max was a star of Old Underground Hollywood. Of course, Marilyn Monroe’s crypt is there (now with our old friend Hef next-door), and for Max, Marilyn was the personification of fun, as well as the epitome of tragedy. Max also loved “The Dark Marilyn” – our friend, show guest and “Queen of Pin-Up” Bettie Page – now buried just a few graves away from Marilyn. It hurts so deeply to say farewell to Capt’n Max, but it helps to feel he’s in good company.

Then it was time for the cremation itself at Valhalla Crematorium. Max was no Viking and Im hardly a Valkyrie, but for a moment, I wished I lived in one of those cultures where the weeping widow throws herself onto her husband’s funeral pyre and goes up in smoke along with him. But I don’t, so I just cried and hugged my fellow mourners, even people I know tried to hurt Max and me… because they are people too.

As we grieved the great loss of Capt’n Max, some mentioned the anti-ICE protests raging outside, and everyone agreed that Max would support the protesters. Despite or maybe because of his own princely lineage, Max always backed the anarchists over the monarchists, just one of many things I loved so much about him.

In a few weeks, we will hold a Capt’n Max Memorial Celebration in Bonoboville and online. If you’d like to participate in person or remotely, please email or call us at 626.461.5950.

Maximillian Rudolf Leblovic Lobkowicz di Filangieri is survived by his brother Charles Lobkowicz; son Michael Leblovic; daughter Daniele Macdonald; daughter Kari Schiaman; son Jonathan Dreksler; grandchildren Anna Baer, Talia Amato, Paige Belmont, Madix Leblovic, Jacob Schiaman, Juliet Schiaman; great grandchildren Taylor Amato, Levon Baer; cousins Giovanni Rossi Filangieri and Anna Aliena Ciriello; and many beloved friends. And by me. I remain his Admiral, his Girl, his Suzy, his beloved, as he was and will always be mine.

Good sailing, my Captain. Your Admiral will be in your arms again very soon. Meantime, I’ll try to take care of Bonoboville with the help of a lot of people who love you.

The goal is the journey, and (ready or not) the journey continues.