AU

Poland has more gold than the European Central Bank and has no intention of slowing down

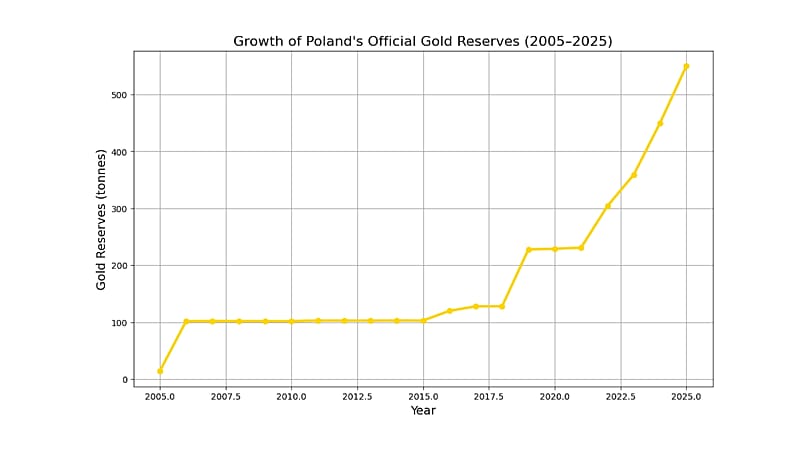

The National Bank of Poland has increased its bullion reserves to around 550 tonnes, valued at more than €63 billion.

The President of the National Bank of Poland (NBP), Adam Glapiński, has emphasised for years that gold plays a special role in the structure of reserves.

It is an asset free of credit risk, independent of the monetary policy decisions of other countries and is resistant to financial shocks.

High gold reserves also contribute to the stability of the Polish economy.

The bank's ambitions are far-reaching: the target is to have 700 tonnes of gold and the total value of bullion reserves to be around PLN 400 billion (€94 billion).\\

As recently as 2024, gold accounted for 16.86% of Poland's foreign exchange reserves. Estimates at the end of December 2025 showed a jump to 28.22%, marking one of the fastest changes in the structure of reserves among central banks worldwide.

The largest transactions were carried out in the final months of 2025, during a period of heightened market volatility and geopolitical tensions.

On the initiative of Glapiński, the NBP's management board has decided to further strategically increase the share of gold.

Glapiński announced earlier in January that he would ask the board to adopt a resolution to increase reserves to 700 tonnes of bullion.

Investing in gold

According to analyses by the World Gold Council, 2025 brought a continuation of the global trend of gold accumulation by central banks. With few exceptions, most countries increased their holdings, treating bullion as a strategic hedge against currency and financial crises.

In 2025, as many as 95% of central banks surveyed expect global gold holdings to increase over the next twelve months.

The reasons why central banks invest in gold are explained by Marta Bassani-Prusik, director of investment products and foreign exchange values at the Mint of Poland.

"One of the key motivators for central banks is the independence of the gold price from monetary policy and credit risk. Equally important is asset diversification and reducing the share of the dollar and other currencies in reserves," she explains.

Experts point out that not all central banks report the full scale of their purchases. China or Russia are often pointed to in this context. Some market observers interpret these actions as part of preparations for an alternative money model, in which gold could play a much greater role than before.

More gold than the ECB

The information that Poland now holds more gold than the European Central Bank (ECB) is not only symbolic. The ECB manages the monetary policy of the eurozone, but its own gold reserves are relatively limited and the burden of owning bullion lies mainly with the national banks of the member countries.

The ECB's gold reserves amount to around 506.5 tonnes. Against this background, the scale of the NBP's holdings - 550 tonnes - is impressive and strengthens Poland's position in the European financial architecture.

However, critics of the NBP's extensive acquisition of gold point out that the funds earmarked for the purchase could be placed in bonds, which generate interest income. Indeed, gold does not provide current income.

Record prices and forecasts for 2026

The NBP's purchases have coincided with historic records for gold prices. Although the rate of listing growth may slow down in 2026, forecasts from major financial institutions remain optimistic. ING estimates an average price of around $4,150 per ounce, Deutsche Bank says $4,450 and Goldman Sachs raises its forecast to $4,900. In a scenario of strong global demand, J.P. Morgan allows for as much as $5,300 per ounce.

"Rising demand from central banks is a response to economic tensions and dynamic geopolitical changes. Although institutional purchases do not directly translate into prices, they indirectly influence the decisions of individual investors," Bassani-Prusik emphasises.

Gold returns to the favour of investors

For the NBP, gold is an element of the country's long-term financial security strategy.

As Mint of Poland experts note, the greater the uncertainty in the markets, the greater the interest in assets perceived as a "safe haven." There is also a growing awareness among retail investors of the role of gold in long-term capital protection.

However, some economists oppose this thesis and feel that a high proportion of gold may not meet the needs of flexible reserve management in a modern economy and funds could be better allocated in other, more productive investments.

Reaching 550 tonnes is an important milestone, but announcements of further purchases suggest that Poland has not yet said its last word. In a world of rising geopolitical tensions and a changing financial order, gold is once again becoming one of the key assets and Poland wants to be at the forefront of this game.

Barrick’s North America spin-off hinges on Newmont’s approval

Canadian miner Barrick’s efforts to spin off its North American assets will hinge on the company’s joint venture partner Newmont, according to documents seen by Reuters and former Barrick executives that demonstrate a reversal of fortunes for two global mining companies.

Denver-based Newmont’s power over Barrick’s strategy is a significant change from a few years ago when the Canadian miner had hoped to buy Newmont’s minority stake in the Nevada mines. A decade earlier, Barrick tried to acquire Newmont.

Newmont has the first right of refusal if Barrick tries to sell its stake in Nevada Gold Mines (NGM), the company’s main North American asset, the documents show. Barrick owns 61.5% and Newmont 38.5% in the mine.

Last year, Barrick announced a restructuring of operations to carve out the North America business from riskier operations in the rest of the world, following former CEO Mark Bristow’s departure.

Barrick’s proposed initial public offering of North American assets includes NGM, Pueblo Viejo mine in the Dominican Republic and the underdeveloped Fourmile mine, also in Nevada.

In filings made with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, the joint venture agreement between Barrick and Newmont specifies that either party must offer its Nevada joint venture interest to the other member before it considers selling to a third party. Any transfer of shares requires the consent of the other party, the documents seen by Reuters show.

Barrick will also need Newmont to fund the capital for Fourmile, according to a person aware of the development which the miner has been touting as its future flagship asset and will also become part of the IPO. During a call with analysts in October 2025, Newmont’s incoming CEO Natasha Viljoen said the company was waiting for some information from Barrick before committing additional capital.

Barrick’s effort to restructure, potentially by splitting into two entities, is one of the most anticipated mining stories of 2026, given strong investor interest in gold bullion with prices hitting successive record highs. The company is expected to outline its plans in February during its Q4 earnings.

In an email response, Barrick said it respects the joint venture with Newmont and abides by all the terms. Newmont spokesperson said the company’s Nevada Gold Mines joint venture agreement has not changed from what is publicly available.

“Regarding Barrick’s potential IPO of its North American gold assets, Newmont does not have any information above and beyond what is in the public domain,” Newmont spokesperson said. The company did not comment on whether it will fund the Fourmile expansion.

Although Barrick shares jumped 130% in 2025, the company’s returns have been lower than its peers in the last five years, gaining 52% over the period while rival Agnico Eagle jumped 142%. Barrick is still considered undervalued.

Newmont’s say over the sale of the Nevada mines despite having only a minority stake in them is unusual, according to three executives aware of the restructuring efforts. The current contract was set up after years of back and forth between the companies, where Barrick in 2019 was keen to buy Newmont. The merger did not happen, and both companies struck a joint venture for Nevada.

“Newmont has done a really good job of being able to call the shots, it was not long ago that Barrick wanted to buy Newmont,” said a former executive of Barrick aware of the joint venture details.

Barrick had a tumultuous year in 2025. Mali’s military government seized its mine there and incarcerated its employees before the company negotiated a deal to get the mine back and its employees released. Barrick’s CEO left, and the company is looking to restore investor confidence under the leadership of chairman John Thornton.

Interim CEO Mark Hill is running the company while Barrick hunts for a new CEO, who must deal with large institutional investors such as BlackRock and activist firm Elliott. This month, Barrick appointed Helen Cai as new chief financial officer. The North America business is valued at around $42 billion and analysts expect the new company could trade better than the current combined entities.

On Friday shares of Barrick were trading up by 1.90% at the Toronto Stock Exchange and Newmont shares were trading up 1.52% at New York Stock Exchange.

(By Divya Rajagopal; Editing by Caroline Stauffer, Veronica Brown and David Gregorio)

Mali’s president tightens direct control over key mining sector

Mali’s military leader has created a new ministerial-level role to oversee the mining sector, strengthening the presidency’s direct oversight of the critical gold industry, and appointed a former Barrick Mining executive to fill it.

Legal documents governing the role show the minister will have powers to supervise mining policy implementation, monitor compliance with the mining code, and review reports submitted by title holders – responsibilities previously handled by the mines ministry.

According to a January 19 presidential decree, Hilaire Bebian Diarra, an earth-science specialist who switched from Barrick to the government last year while leading negotiations for the company over control of the Loulo-Gounkoto complex, has been appointed to the role.

The Malian national was named special adviser to the presidency during the bitter dispute over Mali’s top industrial gold mine, as Assimi Goita’s government pushed for higher taxes and greater state participation in mining projects.

The move was widely seen as a strategic blow to the Canadian miner.

Diarra was not immediately available for comment.

Stronger structures to oversee mining

Mali is one of Africa’s biggest gold producers, and several national mining forums in recent years have urged the creation of stronger structures to oversee security, compliance, and community impacts in its mining industry.

A senior government official said the presidency has assumed the lead on mining oversight, with key exploitation permits decided by the presidency and contract talks – including the Barrick dispute – also run from the presidential palace.

The finance ministry meanwhile now fronts fiscal matters, and the mining ministry focuses on regulation.

Diarra’s elevation comes as Mali tightens its grip on the mining sector, its biggest revenue generator, under a 2023 mining code that helped recover 761 billion CFA francs ($1.2 billion) in arrears, the government said in December.

The tougher code rattled miners and triggered a two-year standoff with Barrick, pushing industrial gold output down by 23% in 2025, provisional mines ministry data showed.

(By Tiemoko Diallo; Editing by Maxwell Akalaare Adombila, Jessica Donati and Jan Harvey)