Statements opposing the US military assault on Venezuela and kidnapping of President Nicolas Maduro and National Assembly MP Cilia Adela Flores de Maduro from Socialist Alliance (Australia), United Left Platform (United States), Indonesian left groups and trade unions, Partido Lakas ng Masa (The Philippines), Socialist Party of Malaysia, Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation, and Social Movement (Ukraine)

Australia: No war on Venezuela! Scrap AUKUS!

Socialist Alliance, January 4

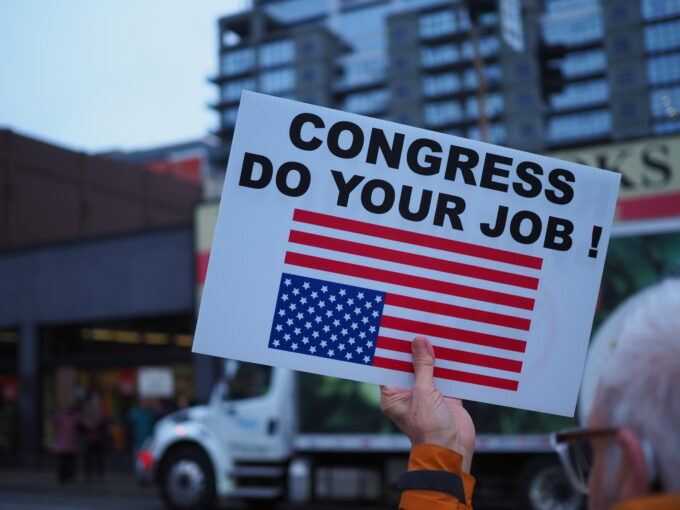

Socialist Alliance strongly condemns United States President Donald Trump’s military invasion of Venezuela and demands that the Australian Labor government rejects the US’ flouting of international law and breaks the AUKUS war alliance.

We stand with the people of Venezuela who are defending their sovereignty and support the emergency protests being organised across the country.

The US’ bombing of at least two military bases in Venezuela’s capital, Caracas, and its abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Adela Flores de Maduro is a reminder of Trump’s lawlessness and lack of commitment to democracy.

This latest act of war comes after illegal attacks over the past few months, including the US navy blowing up small boats near the Venezuelan coast and Colombia’s Pacific coast. More than 100 people have been killed this way.

The US military build-up, including warships, planes and soldiers in the Caribbean, is being posed as necessary to fight drug trafficking and narcoterrorists, despite no evidence being produced.

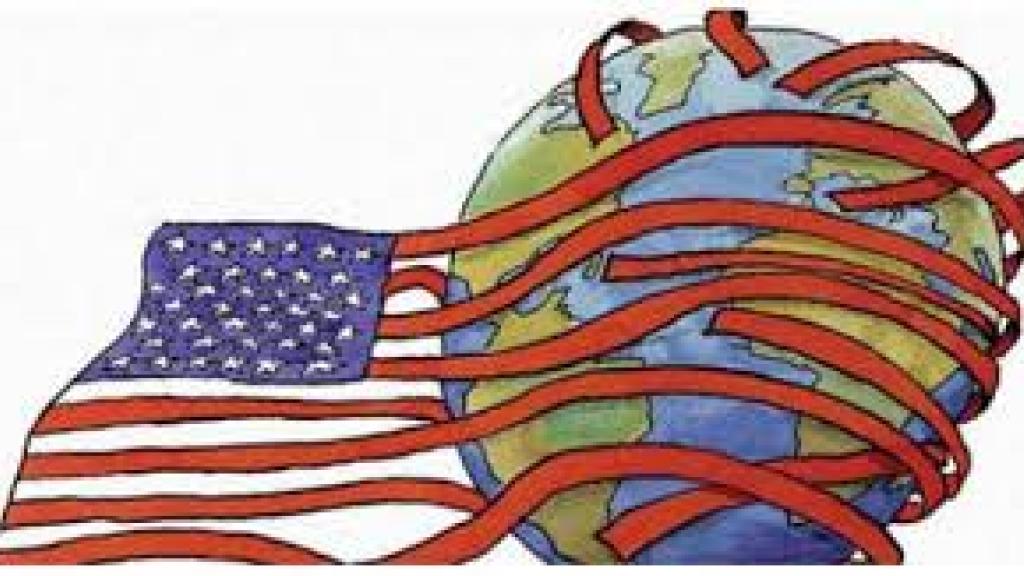

US imperialism’s plan is to impose full dominance through various means including: military (target strikes, threats of war); economic (tariffs, naval blockade); and political (support for far-right allies).

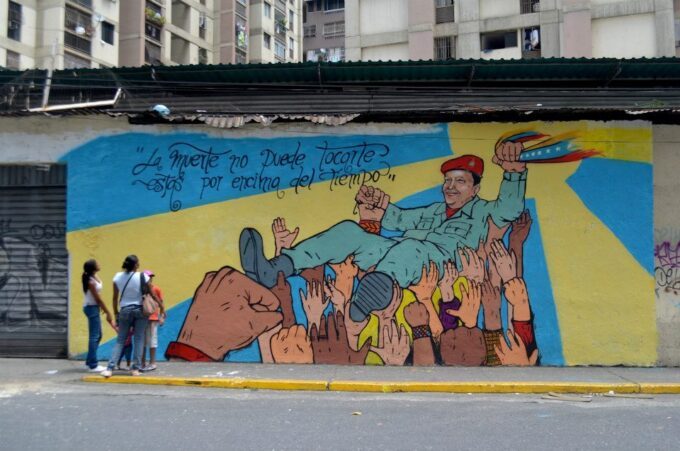

For more than 20 years, the US has been trying to overthrow the government of Venezuela, which was led by President Hugo Chavez from 1999 until his death in 2013, and which is now led by Maduro.

It has supported attempted coups and imposed an economic blockade preventing Venezuela from participating in international trade. The US sanctions have caused great suffering to the Venezuelan people.

The attack on Venezuela is US imperialism’s latest attempt to install a pro-US government there, even though the Trump administration has said it would rule Venezuela for now.

Venezuela and Colombia have criticised Trump’s policies in the Middle East, including US support for Israel’s genocide in Gaza.

The US has repeatedly declared it wants control of Venezuela’s oil deposits - one of the largest in the world. It also made this clear by seizing Venezuelan oil tankers.

Socialist Alliance is also deeply concerned by the outright flouting of international law this attack represents and the lack of criticism from the Labor government.

Labor must immediately condemn the US extrajudicial attacks and break the US war alliance – which AUKUS represents.

The US has said Colombia, Mexico and Cuba are next in line for such aggression. Australia must not agree to Trump’s new Monroe doctrine. Albanese must call out the US’s attack on a sovereign country.

All those who support democracy and the rule of law should step up solidarity with the peoples of the Americas and help build the broadest possible campaigns to defend self-determination there.

We must also pressure Labor to break its alliance with US imperialism, including cancelling the AUKUS agreement and closing US military bases.

Socialist Alliance encourages you to join your local “Hands off Venezuela” rallies.

We support a foreign policy based on peace and justice therefore we demand;

- Stop US attacks on Venezuela!

- Stop the US military operations in the Caribbean and withdraw all warships, planes and troops!

- Stop all US interference and interventions in Latin American domestic politics!

- Shut down US military bases in Australia!

- Scrap AUKUS now and break from the US military alliance!

- Immediate release of Nicholas Maduro and his wife Cilia Adela Flores de Maduro

United States: United Left Platform calls for mass resistance to US imperialist attack on Venezuela

The United Left Platform, January 6

The United Left Platform, a coalition of revolutionary socialist organizations in the U.S., completely and unequivocably condemns the Trump administration’s illegal and unwarranted military attack on Venezuela and kidnapping of President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, the former President of Venezuela’s National Assembly. This aggression poses an ominous threat to any power or person that stands in the way of Trump’s effort to secure U.S. imperial control over Latin America, its most important “sphere of influence.”

In the dead of night in the early morning of January 3, U.S. military forces attacked the Fuerte Tiuna military base in Caracas where Maduro was thought to be residing as well at the La Carlota airport and Higuerote airport to the east of Caracas. Air strikes by planes and helicopters were also reported at La Guaira and Aragua states. The elite army unit Delta Force captured Maduro and Flores and flew them in chains to a prison in New York.

In comments made hours after the assault, code-named Operation Absolute Resolve, Trump made it clear that the attack is but the beginning of his effort to take direct control of Venezuela. “We will run the country until we have a just transition—we can’t take the chance that someone other than us takes over Venezuela,” he stated, adding, “we are willing to wage a second and much larger attack—we are ready to do so right now.”

We should be under no illusions that Trump intends to allow any political power or personage to run Venezuela that is not under the control of the U.S. This is not just regime change—it is a formula for possible occupation, beginning with the U.S. taking total control of Venezuela’s oil and mineral resources.

Whether or not the Trump regime succeeds in this outrageous display of imperial arrogance depends on developing the strongest and broadest possible opposition to his efforts by those of us in the U.S., in Venezuela, and internationally. We urge everyone opposed to war and neocolonial domination to make your voices of opposition heard in the streets, workplaces, and unions.

As revolutionary socialists, we have no illusions about the nature of the Maduro regime, which was neither revolutionary nor socialist. However, the present and future of Venezuela is not for anyone to decide other than the people of Venezuela. We stand with all who seek to defend its right to self-determination.

Trump’s claim that the administration is motivated by controlling the shipment of drugs to the U.S. has no more basis in reality that his assertion that “crime has been totally eliminated” in Washington, DC and other cities by sending in the national guard. Less than 10% of drugs entering the U.S. come from Venezuela, while Trump recently pardoned one of the biggest drug kingpins in Central America, former President Juan Orlando Hernández of Honduras. His attacks on vessels off the coast Venezuela that have killed 110 people in recent months, like the January 3 assault and kidnapping that has killed untold numbers of others, is largely driven by his desire to obtain control of a country with the largest known oil reserves on earth.

However, the attack on Venezuela is not only about oil. Also in play is the effort to enact the Trump Doctrine that proclaims the U.S. now has the right to intervene anywhere it wishes at any time to secure total control of its most important spheres influence—while acknowledging Russia’s and China’s efforts to dominate their respective spheres so long as it coincides with U.S. interests. This is the multipolar imperialism that has now emerged with the collapse of the much heralded (but failed) neoliberal world order. As Trump declared in boasting of the U.S. seizure of Maduro, “America will never again allow foreign powers to drive us out of our own hemisphere.” We must combat this reactionary agenda by engaging in mass resistance to the U.S. attack on Venezuela.

Indonesia: Stop US imperialist military aggression, free Maduro!

Initiated by GEBRAK, January 8

On Saturday, January 3, 2026, at 2:00 a.m. local time, the United States (US) imperialists launched a military attack on Caracas, El Higuerote, Miranda, La Guaira, and Aragua, Venezuela. The attack was accompanied by the kidnapping of President Maduro and his wife. The attack killed at least 40 Venezuelans. US President Donald Trump also ordered a blockade of all oil distribution in and out of Venezuela. This demonstrates the true intentions of the US imperialists in attacking Venezuela. This step is the culmination of a series of criminal acts by US imperialists against the sovereign nation of Venezuela, which has never provoked and has never posed a direct military threat to the United States.

A series of recent US imperialist operations have included outright piracy on the high seas, bombing and shooting at small boats in the Caribbean, and the massacre of Venezuelan citizens on board. These victims were almost certainly innocent fishermen. These actions also included the seizure of tankers carrying Venezuelan oil – and the seizure (read: theft) by the United States. All of these operations were carried out under the pretext of eradicating Venezuelan drug gangs, culminating in Maduro being accused of being a ' narcoterrorist'. Although there has never been any hard evidence to prove this.

The US monopoly seeks to impose its interests through threats, economic warfare, illegal blockades, political pressure, and brutal military force. These plans constitute coercive measures that not only violate sovereignty and international law but also threaten the peace, stability, and right to life of the Venezuelan people and the security of the Latin American region as a whole. These actions are the most blatant manifestation of modern imperialism, which seeks to shackle a free nation.

Equally important, as members of the working class and people's movements, we affirm that imperialism, war, and blockades have deepened the oppression of women. The US stranglehold has worsened access to food and healthcare, increased the burden of unpaid care work, and increased the risk of sexual violence, reproductive health damage, and structural impoverishment.

War and militarism are the most extreme manifestations of women's oppression, a system that normalizes violence, domination, and conquest. Within the framework of imperialism, women's bodies, the bodies of the people, and nature are treated as legitimate objects to be controlled, exploited, and sacrificed for the sake of power and capital accumulation. US imperialists openly stated in front of the mass media that they were targeting Cuba, Mexico, and also Colombia. This is an alarm for world democracy and international law. US imperialists clearly violated Article 2 paragraph (4) of the UN Charter which states:

Each member state is prohibited from using or threatening the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any other state, or in any manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations.

The military attack on Venezuela and the statement sent a clear message that the US intends to dominate and subjugate the entire continent by mercilessly punishing any government that stands in its way. A method more akin to the mafia than to international peace.

Today, we must face the reality that Venezuela, a small Latin American country, is at a significant disadvantage when confronted with the overwhelming military might of US imperialism. The solidarity of the working class and people worldwide is urgently needed to delegitimize US imperialist aggression. Therefore, GEBRAK and the organizations listed in this statement declare:

- Reject military intervention against Venezuela!

- Free Maduro immediately!

- Stop the US economic embargo on Venezuela!

- Stop cooperation with US imperialists!

On behalf of the Labor Movement with the People and supported by:

KASBI CONFEDERATION, KPBI, SGBN, KSN, SYNDICATION, JARKOM SP BANKING, KPA, SEMPRO, KPR, FPBI, SMI, LMID, FIJAR, LBH JAKARTA, YLBHI, FSBMM, FSPM, FKI, SPAI, WALHI, GREENPEACE, TREND ASIA, COMRADE, ALLIANCE OF INDEPENDENT JOURNALISTS, KONTRAS, BEM STIH JENTERA, SPK, RUMAH AMARTYA, PEMBEBASAN, LIPS, MAHARDHIKA WOMEN, KSPTMKI, DFW, PKBI, SOCIALIST UNION, SOCIALIST YOUTH ORGANIZATION, PPR, FMN, GMNI JAKSEL, SPRI, SEMARAK UPNVJ, AMP.

The Philippines: Oppose the criminal US attacks on Venezuela!

Partido Lakas ng Masa, January 4

There is only one word to describe the United States’ attack on Venezuela: criminal. Invading a sovereign country, bombing its cities, and kidnapping its elected president are crimes under international law. These actions are not an aberration—they express the true character of the US empire, which rules through war, coercion, and terror.

A bipartisan war on Venezuelan sovereignty

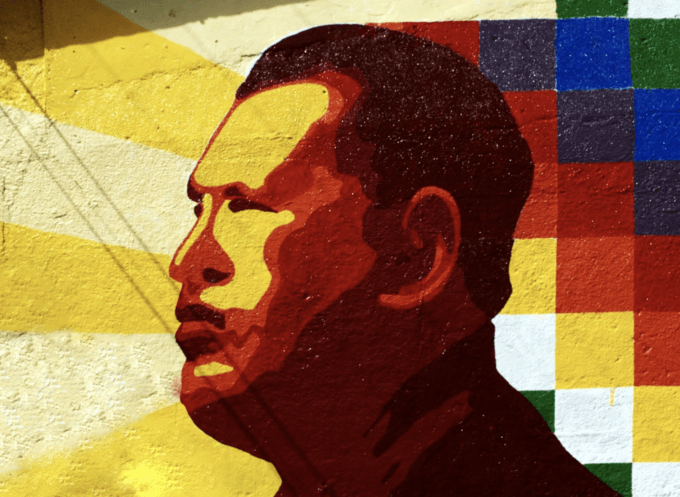

The current assault is the product of a US bipartisan politics of decades-long campaign to destroy Venezuelan sovereignty since the people elected Hugo Chávez in 1998. That democratic choice initiated a redistribution of wealth, expanded popular education, and guaranteed free healthcare to millions long denied these rights—directly challenging imperial control over Venezuela’s resources and future.

The Clinton administration applied political pressure and financed right-wing opposition forces. The George W. Bush administration backed the failed 2002 coup. After Chávez’s death, the Obama administration escalated sanctions and in 2015 branded Venezuela an “extraordinary threat.”

Trump intensified economic warfare and open threats, while the Biden administration largely preserved the sanctions regime that devastated popular living conditions. Trump pulled the trigger, but every administration before him loaded the gun.

The Monroe Doctrine reborn: NSS 2025

This aggression is now openly codified in US doctrine. The 2025 National Security Strategy explicitly revives and hardens the Monroe Doctrine:

After years of neglect, the United States will reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere… We will deny non-Hemispheric competitors the ability to own or control strategically vital assets in our Hemisphere.

The “Trump Corollary” on the Monroe Doctrine is clear: total domination of the Americas, control of strategic assets and supply chains, and the replacement of independent governments with compliant ones. Venezuela—rich in oil, minerals, and strategic position—is a primary target.

Sanctions as economic warfare

Sanctions have been a central weapon in this war. They were designed to strangle the economy, deepen hardship, and break popular resistance. Yet despite immense suffering, Venezuela has endured, reorganized, and pursued greater self-sufficiency under siege.

War for profit: US corporations move in

The motives are no longer hidden. Even as bombs fall, US corporations are already circling like vultures.

According to the Wall Street Journal, senior figures from hedge funds and asset management firms are preparing a trip to Venezuela to scope out “investment opportunities,” particularly in energy and infrastructure.

This is imperial war in practice: destruction first, privatization and plunder next.

Escalation across Latin America

The danger does not stop at Venezuela. According to the New York Times, the real problem is not Washington’s aggression, sanctions, or regime-change policy—but Cuba. In a familiar Cold War reflex, socialist Cuba is once again cast as the hidden hand behind Venezuelan resistance, blamed for undermining “democracy” and obstructing US objectives.

This serves one purpose: to deflect responsibility from US imperialism and reassert the doctrine that no independent political project in Latin America is acceptable unless approved by Washington.

Trump is now openly threatening Mexico and Colombia, laying the groundwork for further intervention. He has declared: “The cartels are running Mexico… something is gonna have to be done with Mexico.”

Trump called out Colombian President Gustavo Petro by name, accusing him without evidence of “making cocaine and sending it to the United States.” “So he does have to watch his ass,” the US president said of Petro, who condemned the Trump administration’s Saturday attack on Venezuela as “aggression against the sovereignty of Venezuela and Latin America.”

This is the language of imperialist prerogative—the assertion that Washington alone decides which governments are legitimate and which countries require US military action. It signals a widening assault on sovereignty across the hemisphere.

Kidnapping, killings, and lies

We denounce the US kidnapping of President Nicolás Maduro and First Lady Cilia Flores. Maduro is now being paraded in Trump’s media establishment in a dehumanizing way as an example to threaten other countries’ opposition to the US imperial might. Any detention, disappearance, or removal of Venezuela’s elected leadership is a grave crime and an act of war.

We condemn the killing of Venezuelan civilians and military personnel and honor those who have died defending their homeland.

We categorically reject the use of fabricated pretexts—including false drug accusations and recycled anti-Cuba hysteria—to justify imperialist violence. These lies are standard tools of intervention and plunder.

A call to oppose imperialist war

This attack must be opposed by all who claim to stand for peace.

Those on the Left who have disagreements with the Maduro government must set them aside and oppose imperialist aggression without qualification.

The assault on Venezuela is part of a wider global escalation. The United States has attacked Nigeria, threatened Iran, and continues to arm Israel as it carries out genocidal violence against Palestinians while bombing Lebanon and Syria. The world is being driven toward a broader war.

History shows where unchecked imperial aggression leads. The last time the world stood this close to catastrophe was when fascist powers invaded their neighbors with impunity. Those acts were rightly condemned as reckless and criminal. The same judgment applies today.

Our demands

We call on peoples and movements worldwide to mobilize in active solidarity with Venezuela—with Latin America, and all nations under threat—to resist this criminal assault on sovereignty, peace, and self-determination.

Now is the time for Left and progressive forces worldwide to unite against imperialist aggression.

We specifically demand that the Government of the Philippines publicly condemn this attack and uphold the principles of national sovereignty and non-intervention.

US Hands Off Venezuela!

Release Maduro Now!

Hands Off Latin America!

No More Wars for Oil!

Imperialism Will Not Prevail!

Malaysia: PSM condemns the US invasion of Venezuela

Parti Sosialis Malaysia, January 3

Parti Sosialis Malaysia (PSM) condemns in the strongest terms the United States’ blatant military invasion of Venezuela- a sovereign country. This act is a violation of international law, the UN Charter, and the fundamental right of nations to self-determination.

The United States has once again revealed its true face , a global bully driven not by human rights or democracy, but by an insatiable greed for oil and minerals. Venezuela’s only “crime” in the eyes of Washington is its vast natural wealth, which the American empire now seeks to plunder by force.

This is not an isolated incident but part of a long, brutal pattern: the U.S. destabilizes, invades, and installs puppet regimes across the world from Iraq and Libya to Latin America; leaving behind chaos, suffering, and broken nations.

We stand in solidarity with the people of Venezuela and their legitimately elected government. We reject all forms of foreign intervention, subversion, and regime-change operations orchestrated by Washington and its allies.

We call on the international community, the United Nations, and all justice-loving nations to support Venezuela’s sovereign right and Demand an unconditional U.S. withdrawal from Venezuelan territory.

If the world remains silent today, no sovereign nation will be safe tomorrow. This is not just Venezuela’s fight from American imperialism. Either we unite to resist this aggression, or we risk neocolonial subjugation once again.

The time for solidarity is now. Stop the invasion. End U.S. imperialism.

S. Arutchelvan

Deputy Chairperson

India: Condemn the US imperialist war on Venezuela! Stand with the people of Venezuela in defence of their sovereignty!

CPI(ML) Liberation, January 3

The people of Venezuela are under attack! In the early hours of January 3, U.S. under the Trump administration unleashed a criminal war of aggression against the people of Venezuela. Reports confirm brutal bombing and military invasion targeting the capital city of Caracas. A social media post by Donald Trump even claims that President Maduro and his wife have been captured and flown out of Venezuela.

This war is not just against Venezuela, but an open threat against every people in the region and across the world who strive to determine their own future free from imperialist dictates.

The same lies used to justify the invasion of Iraq, the seizure of its oil, and the devastation of its people are now recycled as so-called “narco-terrorism” to justify a regime-change operation against President Maduro and the plunder of Venezuela, a country with largest oil reserves in the world.

Trump’s war on the people of Venezuela aims to impose a U.S.-backed colonial order. It seeks to crush the Bolivarian Revolution that overthrew a U.S.-supported oligarchy and returned the nation’s oil wealth to the people. The war is to seize Venezuela’s oil once again for U.S. multinational corporations and install a puppet government to serve imperialist interests.

This war is the latest chapter in the bloody history of U.S. intervention across Latin America and the Caribbean, manipulating elections, overthrowing democratically elected governments, subjugating people’s movements, unleashing bloodshed, and imposing destruction. From Guatemala to Chile, from Grenada to Panama, the U.S. Monroe Doctrine, which treats the Latin American region as its “personal backyard” and which Trump seeks to reinforce, has always meant subjugation, exploitation, and repression, denying the peoples of the region their right to sovereignty and self-determination.

Stand in unyielding solidarity with the people of Venezuela as they defend their sovereignty and their right to determine their own political and economic course, free from imperialist interference.

We call upon all democratic and peace-loving forces worldwide to stand against this imperialist aggression and the attempts to impose a new order of colonial subjugation under the Trump regime.

Hands off Venezuela!

Down with U.S. imperialism!

Ukraine: Oppose US aggression against Venezuela

Social Movement, January 3

The morning of 3 January marks the beginning of a widespread attack on democracy and the relative peace of the peoples of Latin America – and far beyond.

The events in Venezuela, where US military operations led to the capture of President Nicolás Maduro and the declaration of a state of emergency with mobilisation, are yet another manifestation of the escalating imperialist confrontation, the consequences of which will be felt by millions of people across the continent.

The actions of Donald Trump’s administration cannot be viewed as an isolated incident or a ‘forced response’ to the crisis. As before – from the bombing of small vessels in the Caribbean and Pacific Oceans to the sanctions blockade – this is a demonstration of the United States’ power and complete readiness to use violence without trial, investigation or any regard for international law. Pretexts such as the fight against drug trafficking and cartels are used to legitimise aggression. Until recently, the majority of drug precursors were produced in China. The share of drug trafficking through Venezuela is negligible compared to other countries in the region and sea routes.

Excuses about fighting against the ‘drug cartel-linked leadership’ seem particularly cynical in light of Trump’s recent amnesty of former Honduran President Hernández from an American prison – he was sentenced to a long term for involvement in cocaine trafficking, but was released to help his allies in the last election. As in the case of the ‘fight against terrorism,’ the real goal is not protection, but control over oil and mineral resources and the establishment of a regime loyal to Washington.

At the same time, it is necessary to call a spade a spade: Nicolas Maduro’s regime is authoritarian, repressive and deeply corrupt. It has nothing to do with socialist democracy, hiding behind the legacy of Hugo Chavez and Bolivarian rhetoric. Along with the devastating US sanctions, it is the Maduro government’s policies that are responsible for the economic collapse, social catastrophe, extrajudicial killings, malnutrition and mass emigration of millions of Venezuelans. The Maduro leadership has nullified the achievements of the mass movements and social programmes of the Chávez era, instead discrediting left-wing ideas in the region. Parasitising on the population, the regime is sustained by the security forces, restrictions on freedoms and external support, primarily from Russia.

The Kremlin has become one of Caracas’ key allies in maintaining its authoritarian model of government. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has visited Venezuela on numerous occasions, including in April 2023, as part of a tour of Brazil, Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba aimed at mobilising political support for Russia’s war against Ukraine. Although not as notorious as Daniel Ortega, the traitor of the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua, President Maduro declared his ‘full support’ for Russia from the very beginning of the full-scale invasion, and state institutions and the media actively promoted the Kremlin’s interpretation of events.

However, it would be a grave mistake to equate the Maduro regime with Venezuelan society.

Despite widespread propaganda, most Venezuelans did not accept pro-Russian narratives. In the early days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, people took to the streets to protest against the aggression – in a country where demonstrations are regularly criminalised and dispersed. Venezuelans carried Ukrainian flags, chanted ‘Stop Putin’ and openly criticised their government’s alliance with the Kremlin.

This solidarity with Ukraine has deep roots. Since the days of Euromaidan, many Venezuelans have seen the Ukrainian struggle as close and understandable – a struggle against corrupt authorities, external control and authoritarianism. Sympathy for Ukraine stems not only from anti-war sentiments, but also from a rejection of foreign influence, which is crucial to the survival of Maduro’s regime, as well as that of Vladimir Putin – both of whom are under investigation by the International Criminal Court.

Despite widespread propaganda, most Venezuelans did not accept pro-Russian narratives. In the early days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, people took to the streets to protest against the aggression – in a country where demonstrations are regularly criminalised and dispersed.

Since 1999, Ukraine and Venezuela have been building friendly relations, which began under Ukrainian Foreign Minister Borys Tarasyuk, who was received by then-Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez. It is noteworthy that José David Chaparro, the Venezuelan consul in Russia during Chávez’s time, joined the International Legion of Territorial Defence of Ukraine in 2022 and was involved in rebuilding cities destroyed by Russian troops.

That is why the current US aggression cannot be justified even by criticism of Maduro. By proclaiming in its recent National Security Strategy its desire to return Latin America and the Caribbean to the role of a subordinate ‘backyard’ in the spirit of the Monroe Doctrine, American imperialism seeks to ‘clean up’ the region of any regimes that do not fit in with its economic and geopolitical interests, while at the same time strengthening the far-right forces.

That is why the current aggression of the United States cannot be justified even by criticism of Maduro. By proclaiming in its recent National Security Strategy its desire to return Latin America and the Caribbean to the role of a subordinate ‘backyard’ in the spirit of the Monroe Doctrine, American imperialism seeks to ‘clean up’ the region of any regimes that do not fit in with its economic and geopolitical interests, while strengthening ultra-right forces.

The isolation of Colombia’s progressive government and threats to a similar government in Mexico, the strengthening of an alliance with the far-right regime in Argentina at the expense of American taxpayers, support for neo-fascist revanchists in Brazil led by Jair Bolsonaro, and the use of Bukele’s notorious mega-prison in El Salvador to hold deportees from the United States are all part of a single strategy to restore Washington’s hegemony in Latin America.

It is significant that during Trump’s previous term, Venezuelan affairs were overseen by the same Elliot Abrams who was responsible for training, during the Reagan era, the ‘death squads’ of anti-communist dictatorships that carried out more than 90% of the crimes of civil wars in Central American states, such as the murder of about a thousand residents of the village of Mosote in El Salvador.

An externally imposed ‘regime change’ will only deepen the social catastrophe. Like Trump’s racist policy towards Venezuelan refugees, this war is a continuation of a policy of contempt for human life. Even if there are no immediate mass casualties (the 1989 invasion by US Marines to remove the dictator and drug trafficker Noriega, who until recently had been a CIA client in the fight against revolutionary movements in the region, resulted in at least hundreds of civilian deaths), external destabilisation will result in further internal turmoil.

In addition, the potential rise to power of the ‘Trumpist’ wing of the opposition poses a danger. Just as Maduro is a caricature of socialism, the ultra-right and ultra-capitalist course of María Corina Machado is a caricature of the democratic movement. After receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, she emphasised in every way possible that she would prefer to give it to Trump and would support his intervention against her own country. In contrast, the left-wing opposition to Madurism, which is increasingly attracting disillusioned former supporters of the Bolivarian revolution, emphasises the unacceptability of a military scenario and the fact that the fate of Venezuela should be decided by Venezuelans themselves, not by imperialist leaders.

The struggle against Maduro’s dictatorship and the struggle against American imperialism are not mutually exclusive. These are two sides of the same conflict, in which nations become hostages to geopolitical games. That is why today we must speak of solidarity with the people of Venezuela – the same solidarity that Venezuelans showed towards Ukraine in its resistance to Russian aggression.

The people of Venezuela are fighting against the imperialist yoke and are hostages of Maduro’s predatory regime.

Venezuela, we too are resisting imperialism!