No Kings, Fascism, and Democracy

The disease gets worse and worse every year, and the only remedy that will have permanent effect is to abolish private ownership of industry and production for profit, and substitute public ownership with production for use.

— Upton Sinclair, “Production For Use” in New Deal Thought, 1933, edited by Howard Zinn

Donald Trump, after talking with the San Francisco mayor and wealthy business leaders in the Bay Area, has at least temporarily backed off from unleashing a Chicago-style ICE spectacle there.

Donald Trump, after talking with the San Francisco mayor and wealthy business leaders in the Bay Area, has at least temporarily backed off from unleashing a Chicago-style ICE spectacle there.

This is but the latest un-fascist display by the Orange “Hitler,” who couldn’t even bring down Jimmy Kimmel, much less conquer and subdue a string of countries on multiple continents.

In reality, the fascist thesis as applied to Trump doesn’t really hold together well, especially if it is seen as a repetition of Nazism. Unlike Hitler, who was probably the most popular political leader in German history before WWII, Trump struggles to maintain approval in the low-forties and has yet to find a single issue that can forge a robust national unity behind the Dear Leader.

More importantly, he does not seek to establish a new system of representation beyond parliaments and traditional parties to replace the liberal model, as the Nazis did, but to enhance his own fame and fortune by picking the carcass of a collapsing U.S. empire while promising an impossible return to its “glorious” past. He’s a con-man, not a conqueror.

Do we really think that blowing up fishing boats and trying to finish wars in a single weekend to avoid stock market losses (Trump’s strategy in bombing Iran last June) represent the martial glory fascists live for?

Even if Trump wanted to be a Nazi cult leader, he wouldn’t be able to, as mass culture doesn’t exist today like it did in the 1930s. Cultural space these days is highly fragmented due to neo-liberal stratification and anti-social media, which make mass mobilization much more difficult than it was for the Nazis. So while Trump can give us more January 6s, he can’t deliver anything like Hitler’s Nuremberg rallies, and his capacity to transform U.S. culture as a whole is nil.

His talent is for division, not unity, and his erratic policies look more like a staccato sequence of lunatic reality TV episodes than they do the unfolding of a fascist ideological program. Programmatic change requires order, after all, whereas Trump is an agent of chaos, which by definition can’t be normalized.

As a response to Trump’s admittedly harrowing second term, repeatedly declaring, “This is fascism!” in a rising tone of righteous indignation really does not constitute opposition, nor does it achieve anything more than a demonstration of the highly agitated state of the outraged person, which only delights the MAGA base, as such reactions are proof of their “owning the libs.”

Government of the triggered, by the triggered, and for the triggered will not win the day.

Realistically, we are in for an extended period of trench warfare, not a violent subjugation by “fascists.” The contending parties are Trump, who aspires to personal dictatorship based on his victories at the polls, and the dictatorship of money, which has never been elected by anyone. In the middle are we-the-people, who must quickly find a way to create real democracy or else be crushed by polarized elites who agree on nothing more than that the people must shut up and obey.

The beginning of this process may be the fact that Trump has stirred up a broad, uneasy “resistance” movement in the nine months since he returned to the White House. Although still too superficial in its approach, it’s definitely a plus that some seven million people in more than 2700 demonstrations throughout the fifty states of the fragmenting American union recently came together to reject the anti-democratic regression propelled by his administration. Under the slogan “No Kings,” political activists, celebrities, and concerned citizens from all parts of the country denounced the magnate’s ploys to dismantle institutional checks on executive power in an effort to amass boundless personal power unto himself, warning that he has set himself on a path that may soon convert the American republic into a monarchy or worse.

Unfortunately, the “King” thesis appears to be poorly thought through. If Trump is King, then Netanyahu must be the King of Kings, able to reduce the U.S. monarch to his personal lackey at the snap of his fingers. This has to be a major concern for any authentic resistance movement, but at the “No Kings” march in New York City, there was (1) an approved list of chants (!) and (2) “Free Palestine!” wasn’t on it (!)

Hopefully, the movement’s paternalism will disappear and its priorities improve.

In any event, the “King” problem is hardly restricted to the Republican side of the aisle. We got Trump in the first place because Democrats rigged the 2016 elections against the most popular politician in the country — Bernie Sanders — then pumped up Trump as the opponent they could most easily beat, but then couldn’t do so. They barely defeated him in 2020 only thanks to Covid, but then refused to hold primaries in 2024 and put up the vegetable Biden, replacing him late in the campaign with Kamala Harris, who never won a single delegate when she ran for president in 2020. Meanwhile, “King” Trump has taken on and defeated a wide field of candidates running against him over the course of the decade he has dominated American politics.

If Trump is a King, then what are James Clyburn and Nancy Pelosi? They are as entrenched in their positions as any King could be, tolerating no primaries or debates, ruling apparently until death with no possible successful challenge from within the Democratic Party.

If we are serious about transforming U.S. politics we must not only remove Donald Trump from office, but also what the late economist Edward Herman called the un-elected dictatorship of money, the massive centers of private wealth that dominate the state and fund both political parties, precisely in order to prevent any possibility of citizen-led democracy. It is these conglomerations of capital and their fatuous dream of limitless profit (at public expense) that are at the root of our most pressing political problems today.

We have an “immigration problem” because Big Capital holds down living standards abroad then welcomes fleeing workers as “cheap labor” when they reach the U.S., flouting the law and passing on the social costs to others.

We have a “homeless problem” because there is more private profit in dislodging the poor from their homes and “gentrifying” them, than in guaranteeing housing to all as a matter of right.

We have a “healthcare crisis” because capitalism defines medical care as a commodity and rations it according to ability to pay, not medical need. The poorest and sickest people get the worst care and die the youngest; the wealthiest and healthiest people get the best care and live the longest. Got a problem with that? Fuck you.

There is no solution to these and many other problems without challenging the right of capital to transform societies into collections of profitable commodities to be bought and sold by the highest bidder.

American society must be de-commodified by a popular democratic movement aiming to reconstitute the state in order to establish the dignity of labor and broad social equality. This admittedly ambitious goal will necessarily take us far beyond the Democrat-Republican ideological fight into the realm of establishing a culture of social justice, which is what Dr. King gave his life for.

A state dedicated to social justice cannot content itself with being a neutral arbitrator between rival criminal organizations (the DNC and the GOP), but must strive to meet the demands of justice for all. It must cease looking for guidance from financial markets and begin to look to the needs and talents of the people it is supposed to serve. It must dismantle the vast networks of private wealth fastened like barnacles to the state and build democratic legitimacy through policies in the interest of and articulated by an organized majority. Those policies must reverse neo-liberal austerity and return to national development, this time under the aegis of public profit. Private profit can and should continue to exist, but released from subordination to monopoly interests, which will help small business and the entire culture to flourish.

Wages must be substantially raised, employment and medical care guaranteed to all (the latter free at the point of service), and a sovereign financial system capable of channeling savings to innovation and the productive sector established. A public banking system must be created to free the economy from the shackles of usury and convert production into an engine of national development rather than an intermediary of parasitic capital. Without democratic control over credit there can be no real political economy; without political economy there is no real sovereignty.

As things stand right now, we are a nation of dependent paycheck nomads, not independent citizens. We might reasonably call ourselves the United Corporations of America, but not the United States of America, and certainly not a democracy. There can be no democracy under plutocracy.

This is not a call to hand over the economic steering wheel to pointy-headed government bureaucrats, but to subordinate capital to the national interest. Massive concentrations of private wealth can be of no general benefit unless brought under democratic citizen control. Capital should propel a broad network of small and medium-sized productive units to fulfill the economic needs of the American people, not shower the Elon Musks of the world with public money so they can create a trillionaire class. Who needs a trillionaire class?

A citizen-directed state can and should direct, regulate, and guard against private interests re-capturing public decisions and distorting national priorities. Private capital can be an ally of democracy, but never its boss, for it ceases to be democracy at that point. We must create a strong government grounded in democratic legitimacy and technical capacity, capable of disciplining private economic power and putting it at the service of the common good. Only in that way can the state and productive sector be instruments of national sovereignty, rather than a doorway through which an un-elected dictatorship of profiteers enters to restore private domination of public policy.

Our economic goal should not be to administer stagnation and decline, as the neo-liberals have done, nor to surrender to delusions of restoring the robber baron era of U.S. capitalism, which is neither desirable nor achievable. We should dedicate ourselves to crafting a national economic policy that articulates the needs and goals of science, energy, and business, to be carried out by an efficient state planning body capable of coordinating public and private investment in fulfillment of a chosen democratic purpose. Without state direction, the best-laid plans will fizzle out; without broad democratic legitimacy, the economy will fragment and popular sovereignty melt away.

Economic transformation will require educational transformation. We should not have to rely on brain-draining talent from other countries. Our own schools should produce the talent we need. This means an education system oriented towards national production, innovation, and work. Treating workers as mindless atoms of production and lazy maximizers of consumption is an abysmal failure. There is no justification for divorcing production from learning and consumption from creativity – except to perpetuate a professional servant class and highly undemocratic elite governing a failing society. We have had enough of that already.

Of course such an agenda will be dismissed as “Bolshevism” and worse, but we should not let disingenuous calls for “consensus” and “pragmatism” lead to capital subordinating public interest to private gain all over again. Public functions should be plainly in public hands, animated by a program of public profit, democratically determined.

Real transformation does not come from conciliation and deference to private power. It comes from confrontation, breaking with dependence, bureaucratic mediocrity, and parasitic elites. This is a historic necessity, not a misguided indulgence of the non-existent “radical left.” Every real gain, from the abolition of slavery to legal labor unions to universal suffrage of the adult population, was a battle against fear, complacency, and bureaucratic inertia.

Let’s abandon the rearguard struggle to hold on to the remnants of past gains without challenging the legitimacy of private interests dominating the state and leading us to ever greater disaster. We shouldn’t want to perpetuate power, but transform it.

Fascism Is Imperialism Turned Homeward

Admiral Alvin Halsey resigned his post as the Pentagon’s Southern Commander after a fraught meeting with Pete Hegseth involving the US military’s unconstitutional attacks on Venezuelan fishing boats. Since then, the Trump administration has shown ever increasing signs of wanting to wage war on Venezuela.

Picture and think this through: Seagoing US vessels, leaving US ports, carrying cargo far more deadly than cocaine e.g., weapons bound for genocide-crazed Israel.

Imagine: If a foreign power began attacking said vessels claiming they were engaged in transporting deadly substances. The rage for blood vengeance would deafen the ears and numb the collective soul of the nation.

To wit, the US, via the MAGA-Reich, is perpetuating a murderous rampage on innocuous fishing boats in the Caribbean waters off the shores of Venezuela. The soul-dead Big Liars of the Trump, “the Peace President” regime insist they are entitled, by the guiding Almighty hand (caucasoid, of course) of the Sky Daddy to kill, sans consequence, to wage war, without congressional consultation and consent, and simply violate any law, domestic or international, at their Third Reich-adjacent caprice.

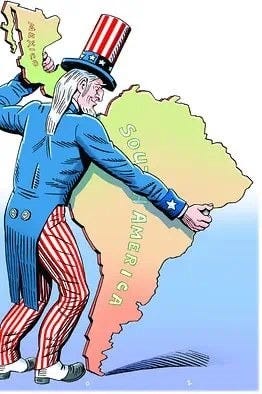

The beneficiaries and operatives of US imperialism believe it is their birthright to impose their blood-drenching will (in the service of their kleptocratic value system) upon the nations of the Southern hemisphere of the Americas (as well as on a global basis).

The only difference here is: the open display of bloodlust evinced by Trumpian psychopathy.

In the Nixon tapes, Richard Nixon and his three piece suit clad goon squad can be heard positing the so-called War On Drugs, in their bigotry rancid minds, was, in reality, a war they were waging on hippies, leftist radicals, Black people and other US citizens of color.

To wit, fascism is imperialism turned homeward. At present, military patrols lumber through domestic cities as the dogs of war are unloosed on weaker nations abroad, all as the worst among us pretend that not only things are normal but the hand of God — reigning over the US’ fifty-first state i.e., White supremacist Heaven — is guiding Trump’s et. al. acts of fascist/imperialist aggression.

Steve Bannon, in an interview with The Economist,

“Well he’s gonna get a third term. Trump is gonna be president in ‘28 and people ought to just get accommodated with that. At the appropriate time we’ll lay out what the plan is, but there’s a plan and President Trump will be the president in ‘28. […] “…He’s an instrument. He’s very imperfect. He’s not churchy, not particularly religious, but he’s an instrument of divine will, and you can tell this of how we’ve, how he’s pulled this off. We need him for at least one more term, right, and he’ll get that in 28.”

“[H]e’s an instrument of divine will.”

You heard it: Bannon, White’s Supremacist Heaven’s prophet on this sin-sullied earth, has foretold the future. Watching from his eternal throne room, MAGA red hat-crowned God has ordained the Third Coming of Jesus J. Trump.

The Celestial Autopen’s writing is on the wall of left-tard Babylon.

What divine punishment will befall those who do not heed the Word the Lord Of MAGA Eternity? Will the Potomac run red with blood as it did in Pharaoh’s kingdom? Will a plague of boils disfigure the pampered epidermises of Woke Hollywood? Will a rain of righteous frogs fall from Heaven to dispatch to Hell the demoniac legions of Antifa frogs of Portland?

History has revealed, whenever a nation’s rulers and assorted minions proclaim they are acting as vessels of God’s will they, in fact, are possessed by the mode of mind and modus operandi of a death cult.

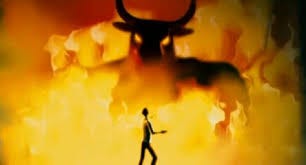

We are, at present, not being confronted by the moral and spiritual equivalence evinced by followers of the First Century mystic/renegade rabbi/challenger of prevailing orthodoxy Jesus of Nazareth; we are subject to the blood-lusting rule of devotees of Moloch.

“Moloch the incomprehensible prison! Moloch the crossbone soulless jailhouse and Congress of sorrows! Moloch whose buildings are judgement! Moloch the vast stone of war! Moloch the stunned governments!”

“They broke their backs lifting Moloch to Heaven! Pavements, trees, radios, tons! lifting the city to Heaven which exists and is everywhere about us!”

— excerpts, Howl, Allen Ginsberg

They will, in the end, break their backs attempting to lift their ruling God Moloch to heaven — but not before they break the (already cracking up) US republic.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro: “There is no superior race. There is no ‘chosen people of God’. neither the United States nor Israel. The ‘chosen people of God is all of humanity.”

Chilean Poet Pablo Neruda limned in lines of verse the avarice-possessed worshipers of Moloch when the Yankee kleptocratic financial elite focused upon and set into motion their greedhead agendas towards the southern hemisphere of the Americas:

With the bloodthirsty flies

came the Fruit Company [i.e., any and all US corporate class fascists and their US government operatives],

amassed coffee and fruit [and oil]

in ships which put to sea like

overloaded trays with the treasures

from our sunken lands.

Meanwhile the Indians fall

into the sugared depths of the

harbors and are buried in the

morning mists;

a corpse rolls, a thing without

name, a discarded number,

a bunch of rotten fruit

thrown on the garbage heap.

— excerpt, “United Fruit Co.” by Pablo Neruda

The US imperialist installed authoritarian leadership was, in time, deposed in Chile, due to a widespread popular uprising that included nationwide general strikes.

Is a similar popular uprising possible in the US?

It would be a hard sell, due to the US citizenry-become-consumers internalization of the (false) value system concomitant to corporatism.

Reality revealed, as the MAGA-Reich’s boot of state is being lowered on the necks of marginalized outsider groups i.e., people bereft of representation, insofar as for the majority of the citizenry, the illusion of everyday normalcy continues unabated.

On a personal basis, my life story makes the inclination to normalize the abhorrent psychologically undoable. In the late 1930s, in Berlin Germany, the Gestapo entered the family home of my maternal grandparents and arrested my grandfather. He, the Jewish owner of a scrap metal business, was accused of crimes against the state.

Henrik Meyer was the treasure of an anti-Nazi resistance group. For the crime of dissent against fascism he was imprisoned in Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Later, my grandmother placed her two daughters, my mother and my aunt, on a Kindertransport bound for the UK. Thus whether it is Israel’s genocidal rampage through Gaza with the agenda of a Zionist version of Lebensraum1 or Christian-nationalist deification of the rightwing propagandist Charlie Kirk or ICE fascistic thuggery perpetrated on those human beings labeled alien others — I feel outrage rising from ancestral memories stored in my very DNA.

Yet under authoritarian rule, life goes on as official cruelty is passed off as the rule of law Trump snarls, US urban areas are crime plagued hellscapes in which lawlessness threatens all that is good and decent. Therefore the only lawless permitted…is the caprice of his fascist shock-troops. Lawlessness should be an exclusive privilege of the state.

An ICE thug in Addison, Illinois, donning an American flag mask, smashes a woman’s car window with her terrorized children inside the vehicle.

All coming to pass as Steve Bannon and his fellow Christian-nationalist asylum inmates of the MAGA dayroom would have us believe the hand of The Lord is guiding the handcuffing of children and the rendering of detainees — innocent of any having committed any crime — to undisclosed “black sites” across the globe wherein they are confined to what are, in essence, no-exit death camps.

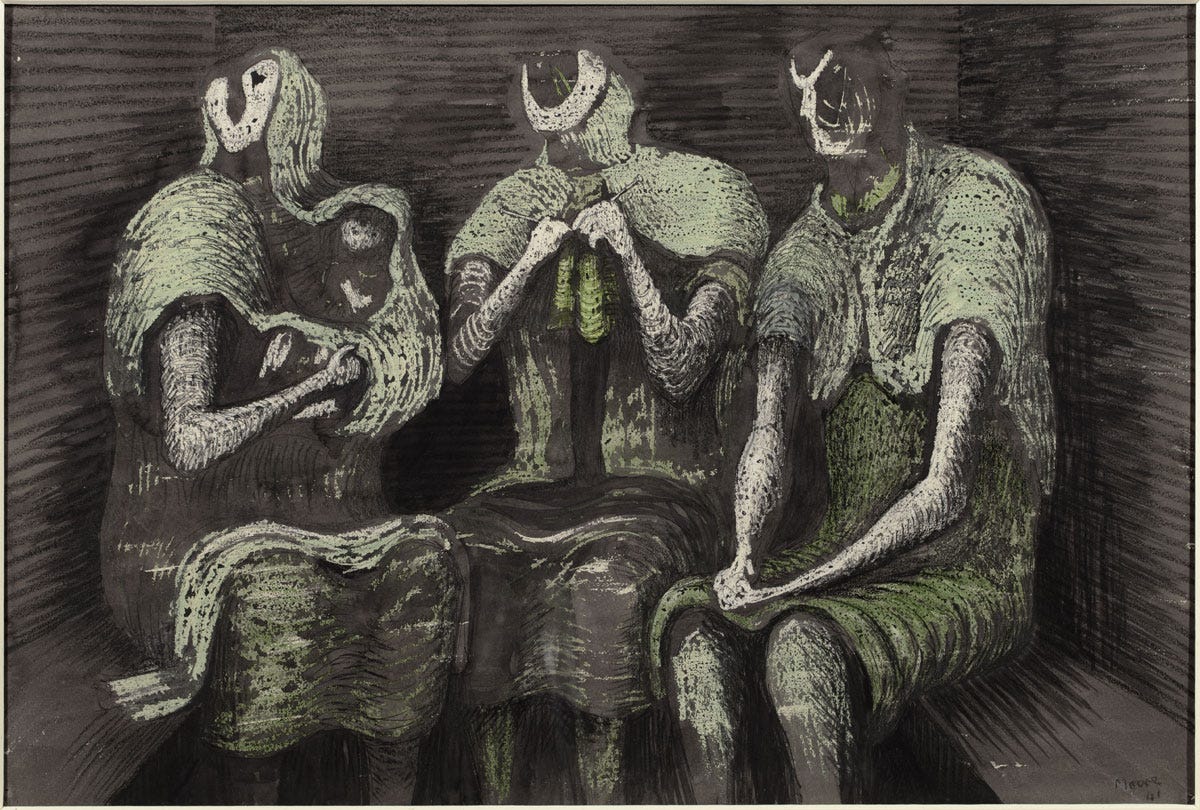

Spanish Prisoner, 1939, by Henry Moore.

Are you angry yet? Do you feel a sense of animus rising from your gut? Anger is libido. For the moment, do not attempt to push it away.

While rightist demagogues retail in displaced anger, on-target, sacred vehemence changes the world for the better.

In closing, I proffer this request: to consider, what is the fate of empire? And, finally, to ask yourself, what will be my part in the unfolding scene?

“Destiny is what you are supposed to do in life. Fate is what kicks you in the ass to make you do it.”

— apocryphal, but often attributed to novelist Henry Miller

Henry Moore, Three Fates

ENDNOTE:

RFE RL

RFE RL