Millenarian Insurrectionary Hail Marianism

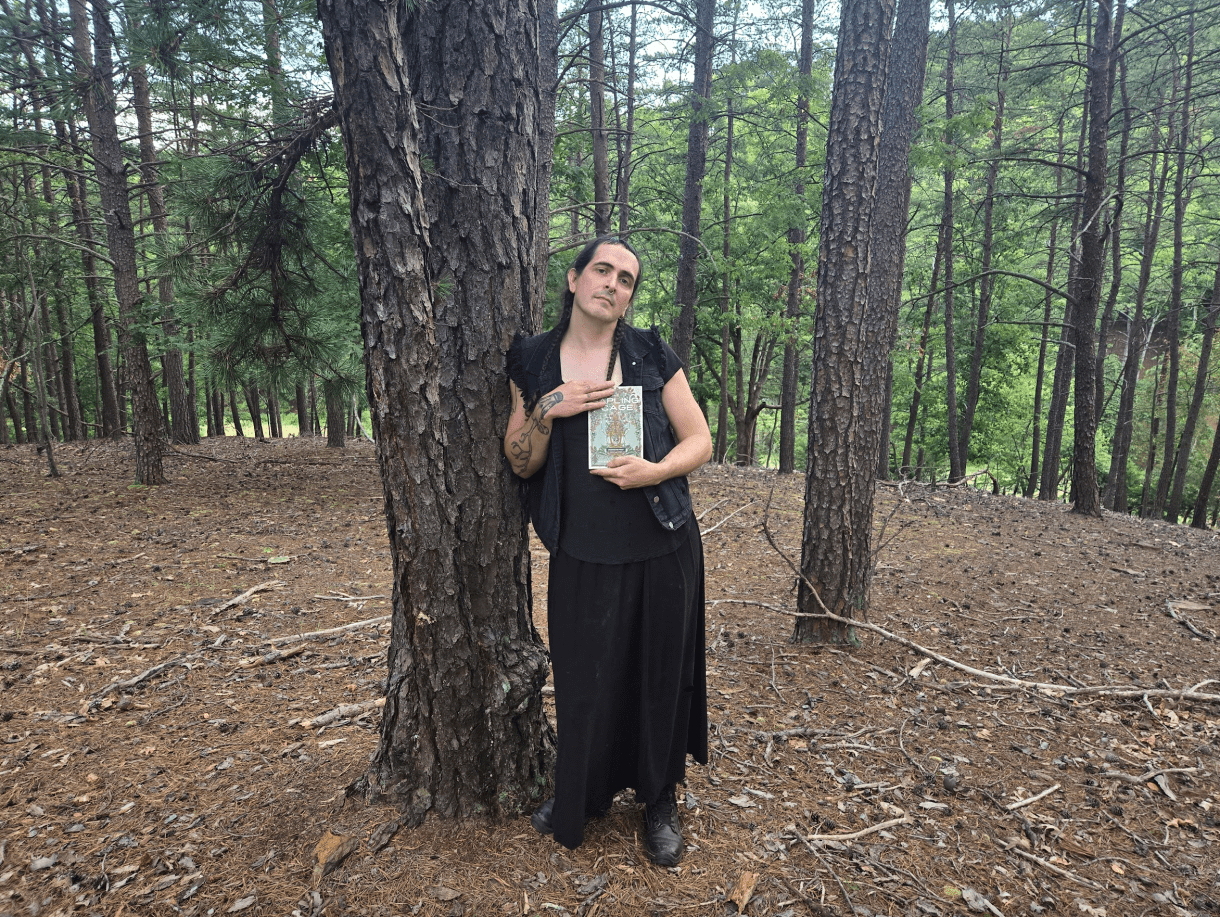

Invecchiare Selvatico Reflects On

Warlike, Howling, Pure

by Areïon

(published by Contagion Press)

"The early anarchist movement was galvanized by its many martyrs…

the anarchist martyrs bore witness to the beautiful idea…

anarchic life is born from anarchic death.”

- Areïon, Warlike, Howling, Pure

“Another word for divine violence is anarchy.”

- Areïon, Warlike, Howling, Pure

“This is the Way.”

- Areïon, Warlike, Howling, Pure

The clock is winding down and there seems to be no path to “victory”, no chance of “winning” (concepts only relevant for those stuck playing Their games). But no, wait… Could it be? Religiosity, self-sacrificial martyrdom, and agenda-infused opportunistic historical re-readings (what the author would likely dismiss as historical revisionism)… that’ll get us to freedom, to anarchy! Awe, well, um, ok? Warlike, Howling, Pure feels like an act of desperation, a last-ditch effort at some sort of ending-times anarchist final triumph or last stand, one that hopefully will not pull other lost souls into its hallowed and insurrecto-thiestic void.

But, before we get ahead of ourselves, let’s take a step back and quickly trace the general path to this anarcho-rapture. First, many action-addicted and street-performing anarchists reconstituted their over-inflated revolutionary goals as insurrectionary (mostly a bad take on an earlier and more interesting Italian version), but most still believed in the inherently authoritarian project of Revolution and of transforming society to their particular idea of a “better world”. Then, some of the more sophisticated of the lot seemed to pay lip-service to criticisms by merely naming them and rebranding to “combative anarchy” and duped a new generation of wide-eyed pseudo-rebels and glorified activists to take to the streets for the “good fight” (a more edgy and militant front of the typical array of symptomatic left-oriented causes). And now, as a bleak darkness envelops, millennial-driven millenarian anarchism and the embracing of a religious warrior epic battle for anti-racist and anti-fascist glory is the latest vision in the desert of insurrectionary anarchism. Little has changed, except for the depth of depression, degree of delusion, grandeur in scope, level of exaggeration and bloated rhetoric. Like a divine message from the gods, Warlike, Howling, Pure opens up this new millenarian “cyclical phase”, which I would argue is actually sick-lical, monotonously repetitive, and spiraling downward.

Add to this bound text a disjointed, convoluted, and religiously-infused Forward by communist-flavored “insurrectionary” author Idris Robinson, someone who has written in previous work that they are apparently always in “pain” except when they are engaged in attack and who has continually pushed the idea of martyrdom. Now Idris’s “pain” is extended to everyone and everywhere with statements like “[Areïon]… demonstrates, incontrovertibly, that our everyday reality, is in fact, hell, in the most literal and concrete sense” and “what you are about to read is nothing short of a life or death struggle, over what is to live and what is to die”. Robinson goes on to further describe the righteous battle of heaven and hell (good and evil without being directly explicit), by offering what thirteenth-century mystic, Aziz O-Din Nasafi, supposedly “teaches us”, which when read through contemporary eyes follows a very similar march that Marx offers in which “all people must first enter hell to reach heaven”. Surprise! Surprise! Surprise!

In a moralistic millenarian-Marxism infused with hyper-religiosity and foaming-at-the-mouth fervor, Idris proclaims from the mount: “The directive is then as clear as ever: either burrow further into the deep recesses of yourself or the moment has arrived for the proletarians to finally storm heaven” and “as religious insight has repeatedly confirmed, hell is nothing other than individual torment without collective deliverance” and “whenever and wherever the exploited and the oppressed transform themselves into insurgents, rebels, and combatants, the gates are crashed, the oath is consummated, and all this is marked by the anointing of the messiah as the collective subject” and “the messianic is therefore a volatile tension constantly traversing the souls of the chosen”.

Then consider, for instance, Robinson’s glowing appreciation for and reprinting of Father George Willie Hurley’s adaption of the Ten Commandments with a list of “Thou shalls and shall nots…” which includes “Thou shall believe that the Ethiopians and all nations will rule the world in righteousness…”, and it is clear that Idris has a disturbing religious, communist, and insurrecto-messianic agenda. Combining Robinson’s forward with Areïon’s four essays which make up this short book, what you have is a recipe for something, in my mind, that is uninteresting, not very anarchist, and a little troubling. To be fair, Idris is far more troubled and troubling than Areïon, but still, Warlike, Howling, Pure appears to be a new depth of desperation and delusion from this particular camp, and comes regrettably from the otherwise provocative Contagion Press.

Obviously, there is an almost absolute and pervasive spiritual emptiness all around. Of course, this has been a deepening general crisis for over a century now (to some extent for multiple millennia), only magnified by science, rationality, politics, and most exponentially by technology, especially the virtual realm. But filling this hole with a millenarian religiosity of perpetual apostolic attack and endless rationales for martyrdom is just plain absurd. If this were a random wing-nut, or even a cute little cult, I could find some amusement in it all. I will admit that I appreciated early ITS and even found later “off-the-deep-end” and whacky incarnations (whether they actually existed or not) interesting on some perverse level. Hell, Charlie Manson gave me some chuckles from time to time and I must confess to a little crush on the bad-ass Sheela of Rajneeshpuram. The author of this book, however, is not some detached actor, but a long-term anarchist who is part of a developing sphere of theory and practice, which, for me, feels significantly different.

A Holy War, as detailed in the book or of any variety, is about as far from my reality as I can imagine. I am against civilization, not the projection and persecution of ideologically un-pure and politicized infidels within it. My spirituality feels unique and grounded in direct organic relations, not myopic thrusts of mythological chest-pumping warrior jiz. My shared spirituality feels intimate and penetrating, not rhetorical and opportunistic. My spirituality is the daily living of getting dirty. It is not removed, epically-driven, and merely metaphorically earthen. In my life, balancing and playing with belief, cynicism, uncertainty, and enchantment is essential in the way I relate to spirituality and is fundamentally at odds with any sort of Holy War.

Whether intended this way or not, Warlike, Howling, Pure reads like the beginnings of an anarchist holy scripture, despite any caveats or disclaimers. But anarchy is neither pious nor evangelical. It is heretical and dispersed. To try to convince others is already an annoying and conceited endeavor, but to suck people’s lives into a personal (or group) vision that is nothing more than another ideological and religious meat-grinding cause is atrocious. Why would we waste the precious little time we have being alive on the delusions of someone’s (or some group’s) desperate cause rather than figuring out, exploring, or remembering how to live freely?

Instead, I choose to carve out as much autonomy as I can outside, on the edges, and even amongst this messed up reality, on my own terms, with the people I love, anarchically not religiously. I’ll defend myself and our people and place on this earth to my last drop of blood, but I will never be a part of any righteous epic battle over what appears to me as another interpretation of good and evil, however its rationalized. Being willing to fight for our lives is much different than feeling an obligation to some larger struggle of cleansing the unrepentant in fire and blood.

It must be said, Areïon brings many important and interesting micro-histories to the table, and in a different context I would appreciate their sharing, but these stories tend to be used as historical fodder in the ultimate agenda of supporting their particular vision of insurrectionary anarchism. From various rebellious sects in ancient China to Spartacus in the Roman Empire to the Iron Column of The Spanish Civil War to a very opportunistic and thin painting of the Diocesan spirit (and animism for that matter), Areïon appears to have a clear goal in using these stories. This, of course, is always the case to some degree, we all do it, but I find their telling particularly manipulative, exaggerated, and predictable, as is the case with most would-be revolutionaries. For instance, just one of many over-stated claims is that the White Lotus Society “attempted to abolish distinctions between genders, and practiced mutual aid”, yet the only evidence of this in the book is the fact that, according to the sourced Elizabeth J. Perry’s “Worshipers and Warriors” in some factions “women were active fighters and group leaders” and “there is some evidence of cooperative economic activities… to aid the poorest participants in the struggles,” So, if that’s all it takes, I guess we are there?

Even when Areïon attempts to move on from the heavily-handed propagandizing of their reading of certain more distant histories and comes closer to the American experience and present times, they fall into an all-too-politicized and sadly too-familiar over-simplistic axis of diametrics: “Whiteness” and “anti-blackness” vs freedom and liberation. As if that is the only choice, the only way to view things, the only way to be situated, the only tensions, the only histories, the only way to respond, or the dominant description of our time. And often when they do this, they intensely project a solidified rationale and reasoning on the players of both sides of this forced and fabricated equation.

If only it were all so simple. If only there were a good and bad, right and wrong, victim and oppressor, then Areïon’s grossly simplistic “Antiracist Holy War” and anarchist millenarian jihad might warrant a second look. But we all know, whether we admit to it or allow it to muddy lame politics or derail thesis projects, that this type of opportunistic over-simplicity only feeds the beast and becomes the negative of what we are against, not to mention the argumentation of “anti-Whiteness” is parallel (with basically the same critique, metrics, and language, just maybe slightly-skewed to account for criticisms) to most leftists these days on the subject of race. It all begins to sound too much like NPR with the volume turned up real loud. Too limited a perspective for anarchists, too trapped, too controlled.

It really starts getting creepy, however, when the author begins writing about taking “loyalty oaths” and “declaring allegiance to all of those excluded” and marginalized by their declared (and offered by academia and activists) enemy in society: “Whiteness”. Deep bonds of trust between our kin (of all sorts and combinations) is essential, but their’s is an overlaid and projected loyalty that rises up to ideology, politics, religion, warfare, and even society in strange ways, not the creative decentralized lives entwined together in the mud and seed that I sink deeper into. Ours is familiar and tribal and anarchistic, not some vague movement of the oppressed holding people accountable for previous sins carried down from generation to generation. Sound familiar? Areïon’s rhetoric and reasonings reflect the vanguardist populism draped in religiosity, as well as the religious fundamentalism that has stained history with the blood of the unbelievers. Areïon has provided a volatile and blood-thirsty religious component for the knuckle-headed, bruit, obtuse, and unsophisticated ideas and actions of Antifa and other uncritical players and activists to use. Luckily, many of them probably don’t read.

Then enters the fire and brimstone, divine vengeance, martyrdom and personal sacrificial duties, and literal sacrifices to gods. And, just like God said to Noah, “Won’t be water, be fire next time!” Areïon assures us without missing a beat of their war-drum that “The fire is here and there is no escaping it” and that “hopefully” the new resurgence in “Spiritualism… will finally spill the blood that the vengeful dead demand. If not, the Furies will hound this guilty land with madness until its crimes are purged.” Not what I am looking for when I engage in a spiritual realm. I look to connect, not project.

Again, if this were some rando on the street corner with snot in their beard holding an upside-down and (perhaps) misspelled placard reading: “God’s Cumming Again!”, I might buy them a cup of coffee and chat a bit for shits and giggles, maybe. Or, I would attempt to avoid the hell out of them. In this case, however, I would say Areïon appears (in the book) to be playing on the fads, trends, depressions, misconceptions, distorted emotions, and the bad takes of so many pseudo-anarchists who are playing games of performance and desperation, in their evangelical attempt to brand their “Antiracist Holy War” and “divine violence” as “anarchy”. It is not. Their explorations in anarchism, adventures in the streets, and excursions in the occult seem to have led them to a very strange and empty place of exaggerated conclusion and dramatic explanation. Violence is not the problem. I have no qualms here. My issues are how and why it is justified and proposed (and most likely will never actually be acted upon in this particular bloody-battled way, luckily I guess).

Even the list of quoted authors has become all-too-predictable. Walter Benjamin, James Baldwin, W.E.B. Du Bois, Ursula K. Le Guin, Diane di Prima, John Brown, Franz Kafka, Deleuze and Guattari, Fredric Nietzsche, etc. (I wonder where Georges Bataille is?) have all made interesting and important contributions (some more than others). But when they are combined in this way, in this type of proposal, it all begins to feel like one continual project of propaganda for a specific flavor of revolutionary struggle, oh, I mean, insurrectionary anarchism, um, sorry, combative anarchy, I mean millenarian anarchism, whatever.

Yes, this world is ending, but to propose that people throw their bodies, hearts, minds, and spirits into its gears is absurd. To ask people to spend their lives preparing for an insurrectionary and apocalyptic bloody wave which will almost definitely never come (especially based on the current crop of hyper-domesticated cyber-humans) is infuriating. But, to attempt to convince people of the heroic value and necessity of martyrdom is inexcusable. Your Black Flame is another con job, another surrogate cause, another guilt-release valve, another act of posturing that will waste precious time, energy, and lives for nothing. Fiction is great, but that’s not how this is presented or intended. Odd, irrational, and even disturbing beliefs can be important, even much needed at times, but this comes off as all-too predictable chest-beating bombastic nonsense mixed with performative spirituality (the kind that religions are built on).

Then we get to the final chapter of Warlike, Howling, Pure, the one that ties it all together, what this was all leading up to, feeding into, Their Way Forward: The Black Flame. We are told that “Anarchy is a spiritual practice, whether its practitioners understand it as such or not. We may distinguish three interwoven currents within it: the devotional, the ancestral, and the initiatory.” First, thanks for defining anarchy for us; funny how it is explained exactly the way you sell it in your book. Oh wait, that’s how propaganda works, it binds things too tightly and grafts ideas, events, and situations to agendas for utilization. And again, spiritual emptiness is a no brainer, especially in this appallingly alienated techno-post-modern nothingness age. Atheism has always been an unfulfilling half-step, rejecting the ideological, moralistic, and authoritarian mindset of religion (a system that enslaves our spirit) but never filling that void with a uniquely individual or tribally-shared spiritual relationship of people and place. So yes, spiritual emptiness is a colossal problem, but stuffing it with this religious garbage seems highly opportunistic.

As with much of the book, there are nuggets, statements, and thoughts that resonate with me in isolation, that I even agree with, but they almost always direct us towards a place I abhor, and this final section is certainly no exception. For instance, I would agree with Areïon, that anarchy is “a force within the world—a spirit.” I often describe it this way, yet to call it “devotional” both traps it and forces us to submit to it, rather than it moving in us. It is not something to serve. It is not something to kill and die for (specifically). It is not a practice or a religion. It is an agent of chaos and freedom that cannot be reified. It is life itself: undefinable, unmolested, unrestricted, uncontrollable.

Even to talk of anarchy in historical terms, as is often the case with certain insurrectionary types like Areïon, seems opportunistic, for we know not, nor live in, those contexts. How it flowed within those anarchic moments and people is purely speculation and often later agenda-derived for propagandistic purposes, not for anarchy. And while I gain personal strength from the written histories and statements of rebellious anarchists like Giuseppe Fanelli, Louis Lingg, or Emile Henry (all mentioned in the text), they are of certain situations and mostly not very transferable or fully understandable to us, especially in regard to martyrdom (of which Emile Henry was absolutely opposed to). This making of propagandist lore is littered throughout the book.

As far as Areïon’s claim that “to name oneself an anarchist is to situate oneself within an ancestral lineage, of all those who have named themselves anarchists before.” Well, yes and no. Intergenerational honoring and exchange is sorely missing in most people’s lives, but this relationship is most potent closer to home, outside of identity, politics, or ideas than most anarchists are willing to reach and is more meaningful in more selective and situational ways than most anarchists move in regard to other self-declared anarchists. If we lined up most people who have called themselves anarchists throughout history, I would have very little to do with most of them, and the closer one comes to our current pathetic subcultural manifestation, the less so. I don’t relate to people who primarily identify with what has become (and in many ways unfortunately always has been for most) a political identity or ideology. My grandmother—riddled with many problems from my perspective—had more to teach me and was more deserving of my love and remembrance than most anarchists.

True rebels, outlaws, drop-outs, deviants, and creative spirits warrant more respect from me and more to pass on than puffed-up play-warriors in some imagined struggle for liberation, and definitely much more than the millenarian insurrectionary religious zealots of this type. The parts of anarchist history that most anarchists fail to remember are the endless repeated mistakes both in theory and practice or the marginally-known exceptions to this norm (see the publishing project Enemy Combatant for some insights here). In the digital age, when every previous anarchist’s thought and action is supposedly at one’s fingertips, why do most continue to skip over the vital parts, have lame generalized and superficial takes, sink deeper into collectivism and leftism, play political games, promote reform, or even worse, martyrdom?

This idea that in “understanding anarchy as an ancestral lineage… anarchic life is born from anarchic death,” follows and promotes this lame logic of intrinsic lineage and martyrdom. Perhaps Areïon is most direct here: “The willingness of the anarchists of old to kill and die — to be martyred — for the beautiful idea enters the realm of the religious, or more properly the devotional, from Latin devotio, to “vow downwards,” originally a battlefield vow to gods and spirits of the underworld of one’s own life in exchange for victory.” So the one thing that is truly our own, our life, we sacrifice for a victory we cannot share in—except in the spilling of our own blood which is promised to the gods? (What about the 72 virgins?) No. The spirit of anarchy does not ask such a sacrifice (or offer empty rewards). It is not a god. If it were, I could only have a heretical and adversarial relationship with it.

To risk our lives for freedom or defense of autonomy or even as some night-time anonymous attack against specific parts of the machine’s apparatus (including individual actors), for sure, but that is very different than the religious martyrdom of some sort of notion of eternal glory and righteousness, I leave that for the multitude of fundamentalists and their endless wars. This all reminds me of a horrible take on the war in Palestine called “Gods Of Gaza”. It had very similar language and ideas as Warlike, Howling, Pure. It glorified Hamas and considered them part of a righteous “Axis of Resistance” (of which the authors situated themselves and anarchists within) which will eventually prove victorious across the globe, and soon! There was so much to criticize in the piece that it overwhelmed me. I burned it during a spontaneous pyre while the eclipse was occurring this past Spring, not as a sacrifice or offering, but as a heretical show of disgust for this type of thinking. My black sun and theirs seem to mean very different things, but that is another story.

The book continues on with Areïon’s faithful cult-like ideas on so-called “anarchist initiation”, filled with “secret rites and symbols, whose mystical significance can only be truly understood by the initiated.” I would agree, anarchy is not for most domesticated humans, but not because they are not anointed in some holy fluids or not in possession of the sacred and ordained black mask that is suggested. Despite its relative simplicity, anarchy is sadly over most people’s slavish heads (situationally not inherently). We are not proselytizers, we live anarchy, but we also are not a cult of those who hold the true wisdom either, mystifying the profane for only the high priests and prophetesses to comprehend and disseminate, making it sacred and removed from the dynamic elements of life. We are not the divine keepers of the holy Black Flame, nor carriers of the corny black and red banners, we are anarchists. We live anarchy, here and now.

As the book concludes with “Eternal Fire”, even when they describe interestingly immoral and more deviant historical (or possibly mythical) situations, martyrdom, self-sacrifice, and dutiful offerings of our blood for what Areïon has turned into a crusade of purity and righteousness is once again the main point, including very loaded and laughable statements like “May Day, the greatest of anarchist holy days”. May Day has never been that important of a day for me, no matter how hard I tried or it got pounded into me. The workerist and martyr angles never got me off. I suppose I can appreciate Beltane a little more, but still, it is not my holy day. I am left to pick through the detached and discarded refuse and make my own micro-cultural points of meaning with people I love.

I want to be absolutely clear: violence, revolt, belief, and spirituality, are not my problem here at all. In fact, they all are important elements to my very being and my relationship to anarchy. Even elements of myth-making, cult-like affinity, and ceremony can be interesting at times in certain ways. It is the “why” and “how” that I take issue with Areïon’s offering of Warlike, Howling, Pure. In times of deep desperation, millenarian, apocalyptic, and martyr-fueled ideas and actions are not uncommon, but as anarchists, they offer absolutely nothing but cautionary lessons. They are only relevant to religious zealots, political opportunists, or hyperbolic rhetorical posturing. “Warlike” is for people fighting for power, “Howling” can be authentically wild, but for most domesticated humans is usually just a bunch of self-aggrandizing hot-air, and “Pure”, well, this is the no-brainer concept anarchists should run from or attack.

So, the clock is ticking, all odds are stacked against us (especially if your lame goal is to transform society into your self-righteous vision of it, rather than fight for your autonomy and freedom from society and for those you care about), Areïon goes back to throw a last-ditched attempt at a millenarian insurrectionary hail Mary pass made of morality, religion and ideology, proposed with fiery rhetoric and opportunistic readings of history and myth, and filled with martyrdom, convoluted ceremony, and your anarchist blood…. Hmmm. Can you say blitz!

(Sorry for the sports reference,cI actually loath most forms of professional competition, but it seemed fitting.)

---------

* Invecchiare Selvatico was a primary editor and writer for Green Anarchy magazine and is the author of Black Blossoms At The End Of The World available from: www.underworldamusements.com or from the author: nazelpickens@gmail.com or PO Box 316 Williams, OR 97544