AFP

October 26, 2023

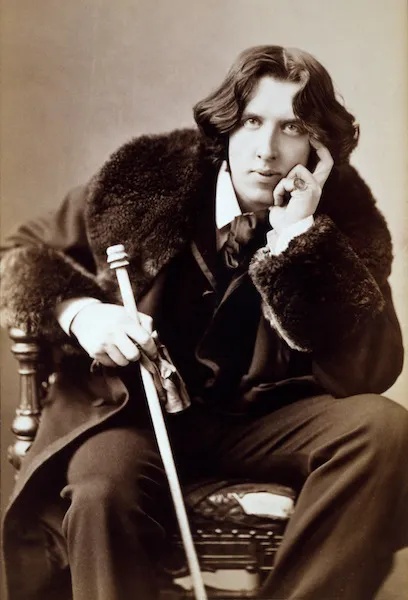

Fangs for coming: visitors admire one of the few portraits of Vlad III, aka Dracula, in Austria's Forchtenstein Castle

Blaise GAUQUELIN with Ionut IORDACHESCU in Romania

Cloaked in a black cape like the infamous count himself, 10-year-old Niklas Schuetz runs through the dark corridors of a hill-top castle in search of the truth about Dracula.

“He was a Romanian prince, not a vampire,” said the schoolboy, as he tripped by torchlight through the nocturnal gloom of Forchtenstein Castle.

The group being guided through the Austrian fortress are eager to sink their teeth into the gripping life of Vlad Tepes, the notorious “Vlad the Impaler”, whose descendants once held the schloss.

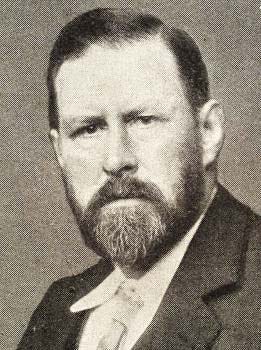

The castle is home to one of the few paintings of the cruel 15th-century prince, and this Halloween its curators are trying to bring the real historical figure out from the chilling shadow of the monster invented by the Irish writer Bram Stoker.

Rather than being a ghoulish fiend, the real Vlad Tepes had for a “long time gone down in history as a positive figure” who courageously fought the Ottoman Turks, said the director of its collections, Florian Bayer.

“More and more people are able to distinguish between the bloodsucking vampire and the historical figure,” he said.

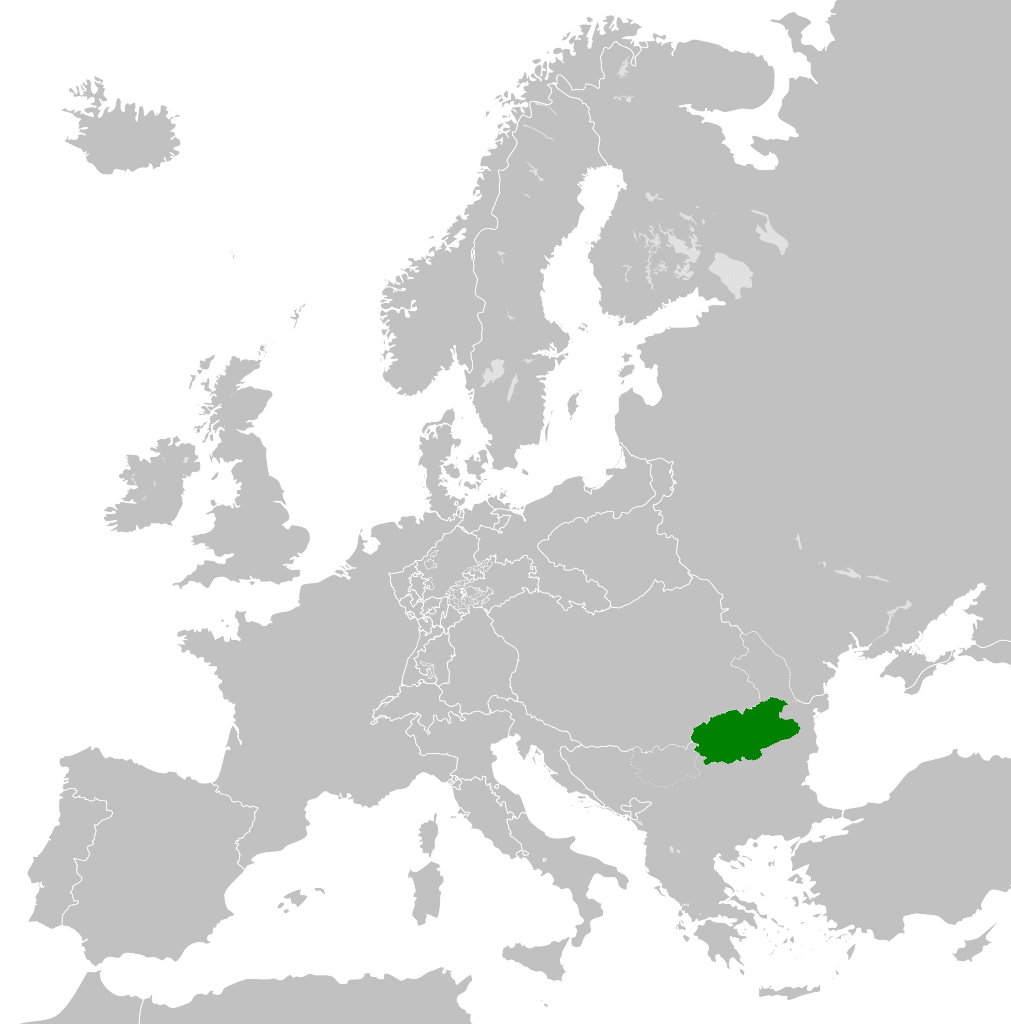

Voivode Vlad III — also known by his patronymic name Dracula derived from the Slavonic word for dragon — once ruled over Wallachia, a Romanian-speaking vassal state of the Kingdom of Hungary.

– ‘Forest’ of the impaled –

Held as a child hostage of the sultan at the Ottoman court, he later turned against his former captors.

In several hard-fought campaigns against the Turks, he struck fear into his enemies by impaling thousands of Turkish prisoners.

This gruesomely slow death was also used against his internal rivals, like “the German merchants from neighbouring Transylvanian towns,” historian Dan Ioan Muresan told AFP.

Tepes was often depicted amidst a “forest” of impaled bodies.

Yet despite his gory reputation, Vlad was a handsome devil and something of a ladykiller, according to Muresan.

He was a “very handsome man with an imposing build”, with long hair flowing over his Turkish-style kaftans adorned with diamonds.

By marrying a cousin of the Hungarian king, he “gave rise to a branch from which the British royal family descends,” the historian added.

Indeed Britain’s King Charles III has repeatedly boasted of their shared blood ties, saying that Transylvania runs through his veins.

– Communist marketing –

The gothic novel by Stoker published in 1897 helped kickstart the modern vampire genre.

Dozens of films later, the fictional Dracula had transformed into a pop culture icon.

“Until the 1960s, Romanians didn’t associate the character imagined by Stoker with Vlad Tepes,” said Bogdan Popovici, head of the national archives in the Transylvanian city of Brasov, home to some of the prince’s manuscripts.

“It was the Communists who started to commercialise it for the Western market to attract tourists,” he said.

While cashing in on selling the vampire myth to visitors, the regime of Romanian Communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu sought to resurrect Vlad as a national hero.

Paradoxically, the Communist regime was careful in differentiating the real Dracula from its fictitious counterpart as it pursued its mission to wipe out pagan traditions.

– Tears of blood –

“Romanians have never recognised themselves in the character, which was born out of a foreign imagination and planted into an exotic reality,” said Muresan.

“It is being exploited as a kind of tourist trap,” he said.

The real Vlad never set foot in Romania’s Bran Castle — widely taken as the inspiration for the lair of Dracula — but it hasn’t stopped it drawing visitors in their droves.

Murdered by his own people in 1476 in the wake of a conspiracy, experts dispute the whereabouts of his remains to this day, with some claiming that his head was sent to the sultan in Constantinople to confirm his death.

A recent Italian scientific study based on the analysis of the prince’s handwritten letters found that Vlad probably suffered from haemolacria, indicating that he could shed tears of blood.

The creepy detail is undoubtedly enough to keep the Dracula myth alive for some time yet.

Wallachia

Wallachia