Sovereignty Is A Sham: The Hypocrisy Of State Power Playing The Rules It Pretends To Follow – OpEd

World leaders claim to uphold sovereignty and international law while bending the rules to serve their own power. This is not a flaw or an exception—it is the very logic of global politics, where norms are tools, not guarantees.

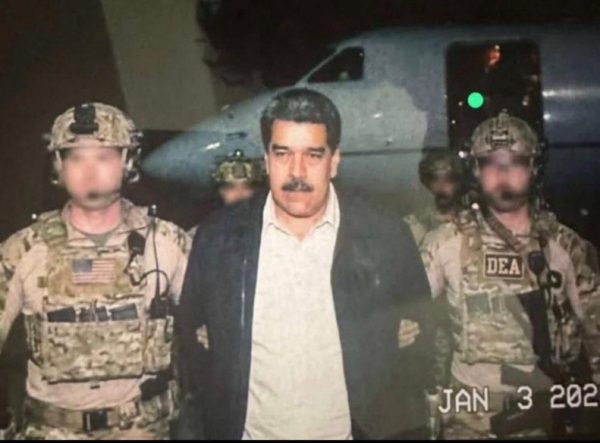

The Kremlin’s declaration that Venezuela “must be guaranteed the right to determine its own future without destructive external interference, particularly of a military nature,” issued after American forces captured President Nicolás Maduro and First Lady Cilia Flores, was already freighted with contradiction. The sentence itself is almost textbook international law—sovereignty, self-determination, nonintervention. It could have been lifted from the UN Charter or the language of decolonization movements across the 20th century. And yet, spoken by a government that invaded Ukraine, leveled cities, displaced millions, and annexed territory by force, the words did not persuade. The words hovered, accusing even as they exposed the distance between what is said and what is done.

The easy response is to call the statement hypocritical and move on. Hypocrisy is a satisfying diagnosis because it preserves the underlying moral architecture. The rule is still sound; the speaker has merely violated it. The norm remains intact even if the norm-breaker does not. But this reassurance is false. What the statement reveals is not hypocrisy as a deviation, but as a structure. It shows how international norms actually function—not as shared commitments, but as instruments deployed when useful and discarded when costly.

This is not a Russian aberration. It is the condition of modern geopolitics.

Sovereignty is one of the most potent ideas ever produced by political thought. It promised an end to endless war by locating authority within borders. It gave language to the anti-imperial struggle. It offered newly independent nations a claim to dignity, autonomy, and recognition. For much of the world, sovereignty was not an abstraction but a hard-won reprieve from domination.

And yet sovereignty has always carried a second face. The same principle that shields the weak also protects the strong. The same norm that prohibits invasion can be invoked to excuse repression. From its earliest articulations, sovereignty was less a moral achievement than a political compromise—a way of stabilizing power rather than transcending it.

After the devastation of World War II, international law attempted to discipline this compromise. The United Nations Charter outlawed aggressive war. It elevated self-determination. It gestured toward a world in which force would be constrained by rules rather than sanctified by victory. After 1945, this compromise was formalized in law. Article 2(4) of the UN Charter prohibits the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, an ambitious attempt to turn the moral intuition against conquest into a binding global rule—one that has been honored more often in rhetoric than in restraint. This legal architecture remains one of humanity’s most ambitious moral projects. Ukraine’s democracy sharpens the injustice of invasion, but it is not its source; the ban on conquest was meant to survive the imperfections of governments, not reward virtue, because once sovereignty becomes conditional, it becomes permission.

But ambition is not enforcement.

From the moment these norms were codified, they were bent. The United States defended sovereignty while orchestrating coups across Latin America and the Middle East. It invoked international law while bypassing it in Vietnam and Iraq. The Soviet Union spoke the language of socialist liberation while crushing uprisings in Hungary and Czechoslovakia. China defends noninterference while exerting relentless pressure on Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and Taiwan. Russia condemns Western meddling while redrawing borders at gunpoint.

No major power is exempt. The vocabulary changes. The justifications evolve. The structure persists.

Political theorist Stephen Krasner called this reality “organized hypocrisy,” a phrase that still unsettles because it refuses comfort. States do not fail to live up to norms accidentally; they affirm them precisely because norms confer legitimacy. Sovereignty is valuable not because it restrains power, but because it can be invoked to justify it. Norms are not abandoned when violated. They are repurposed.

This is why every intervention is framed as an exception. Every breach is temporary. Every violation is necessary. The rule is never denied—only deferred.

Liberals often resist this conclusion. Liberal internationalism depends on the belief that rules matter, that institutions restrain violence, and that progress, however fragile, is real. To admit that norms function instrumentally feels like surrendering to cynicism or realism in its crudest form. So liberal discourse clings to binaries: a rules-based order versus chaos, democracy versus authoritarianism, law versus lawlessness. Hypocrisy becomes evidence of moral failure rather than structural design.

Progressives, meanwhile, often fall into a different distortion. Deeply aware of Western imperialism, they sometimes treat sovereignty as sacred when invoked against Washington but negotiable when violated by states positioned as anti-Western. Power is condemned selectively, depending on who wields it. In early responses to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, some Western left critiques foregrounded NATO expansion as the central explanatory frame—contextualizing Moscow’s aggression primarily as a reaction to Western policy rather than as an exercise of imperial power in its own right. The result is not internationalism, but alignment.

Both responses mistake rhetoric for reality.

Carl Schmitt, a deeply compromised thinker whose insights nonetheless haunt modern politics, argued that sovereignty ultimately resides in the power to decide when rules no longer apply. As he writes in Political Theology, the sovereign is “he who decides on the exception”—highlighting how legalism and moral language can mask this truth. Liberalism, Schmitt warned, dresses up power in norms, making the suspension of rules appear as an anomaly rather than the ultimate expression of authority. History has repeatedly vindicated him. The exception is not an anomaly; it is the mechanism through which power asserts itself.

Humanitarian intervention illustrates this with brutal clarity. The language of human rights has been used to justify rescue and ruin, protection and plunder. Some interventions have saved lives. Others have destroyed states. The distinction is rarely adjudicated by law alone. It is settled by force, narrative control, and what the world chooses to remember.

Hannah Arendt understood that when states rely heavily on moral rhetoric to justify violence, it is often because legitimacy is already fraying; power, she argued, arises from collective consent and rational persuasion rather than coercion. Violence fills the void when that consent erodes. The louder the appeal to principle, the more precarious the authority behind it.

Literature has always seen this more clearly than policy.

George Orwell warned that political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable—to transform invasion into “intervention,” occupation into “security,” civilian death into “collateral damage.” This is not mere euphemism. It is a technology of rule, as he shows in Politics and the English Language.

Albert Camus, writing amid the wreckage of ideological violence, rejected both moral absolutism and moral relativism. He insisted that refusing injustice does not grant permission to commit it. His refusal to excuse revolutionary violence alienated him from the left and earned him suspicion from the right, but it preserved a form of moral seriousness that ideology corrodes, as he makes clear in The Rebel—a refusal to justify ends through violent means that undermines human dignity.

Poets like W.H. Auden captured the dissonance between abstract principle and embodied suffering—the way states speak in nouns while people bleed in verbs, as in his poem “Musée des Beaux Arts,” where the world “goes on” even as human suffering unfolds at its margins. Writers such as Chinua Achebe exposed how colonial power cloaked domination in the language of order and improvement, insisting that the greatest violence was not only material but epistemic: the theft of moral voice that denies whole peoples full humanity.

This is why hypocrisy endures. Not because leaders are uniquely immoral, but because norms function as currency. They legitimize action. They structure debate. Even when violated, they shape the argument. No one claims sovereignty is meaningless. They claim it applies here, not there.

The danger lies not in recognizing this, but in pretending otherwise.

For citizens of powerful democracies, selective outrage is not a personal failing so much as a systemic one. Media ecosystems, partisan identities, and moral branding encourage us to see principle everywhere except where it implicates us. Our violations are tragic necessities. Theirs reveal character.

For the left, the challenge is sharper still. Anti-imperialism loses coherence when it excuses authoritarian violence simply because it opposes Western power. Solidarity with oppressed peoples cannot stop at borders drawn by empires. To critique NATO expansion does not require endorsing invasion. To expose U.S. hypocrisy does not require minimizing Ukrainian suffering. Moral clarity is not achieved by changing uniforms.

If norms are tools, the task is not to discard them—but to refuse their monopolization.

A more honest internationalism would begin by abandoning the fantasy that law floats above power. It would treat norms as fragile achievements rather than guarantees. It would demand consistency not as an expectation, but as a political struggle—one that begins at home.

Such an ethic would resist both cynicism and sanctimony. It would hold violations wrong even when committed by “our side.” It would treat sovereignty not as a slogan, but as a lived condition requiring economic, political, and social autonomy, not just territorial integrity.

When the Kremlin speaks of Venezuela’s right to self-determination, the statement is not false. It is incomplete. It omits Ukraine. It omits history. It omits the speaker.

The real danger is not that powerful states lie about norms. It is that we continue to treat those lies as deviations rather than disclosures—and exempt our own institutions from the scrutiny we so readily apply to others.

To name this is not to abandon hope. It is to ground it. Only by confronting how norms are used can we begin the far harder work of making them mean something at all.

Martina Moneke

Martina Moneke writes about art, fashion, culture, and politics. In 2022, she received the Los Angeles Press Club's First Place Award for Election Editorials at the 65th Annual Southern California Journalism Awards. She is based in Los Angeles and New York.