'MANY OF THESE JEWS IN NEW YORK KNEW TROTSKY, HE WAS VERY POPULAR'

Trotsky’s day out: How a visit to NYC influenced the Bolshevik revolution

Author Kenneth Ackerman explores the life of the Jewish radical in the weeks leading up to the overthrow of the Russian Provisional Government

By JP O’ MALLEY 19 September 2016

Leon Trotsky in Mexico with some American friends, shortly before his 1940 assassination. (Public domain)

LONDON — Between 1881 and 1917, New York was ballooning into the fastest growing and most ethnically diverse metropolis the world had ever seen.

Jews made up over a fifth of the city’s expanding population of 5.5 million. Most came from the Pale of Settlement — a western region of imperial Russia — fleeing pogroms and violent persecution.

The largest Jewish presence in New York was on the Lower East Side, where Yiddish was the language of the streets, cafes, theaters, cinemas, and the Jewish printing press — which was predominately socialist, left wing, and internationalist in outlook.

In January 1917, a strikingly handsome radical-revolutionary, Lev Davidovich Bronstein — otherwise known as Leon Trotsky — arrived into this vast cosmopolitan-cultural-melting-pot.

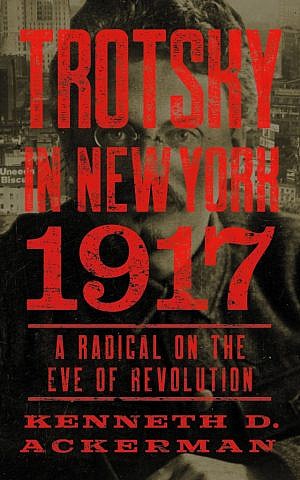

Kenneth D. Ackerman, a lawyer and historian based in Washington D.C., has recently published “Trotsky in New York 1917: A Radical on the Eve of Revolution.”

The book recalls Trotsky’s controversial 10 weeks spent in New York before he headed back to Russia to lead the Military-Revolutionary Committee which carried out the overthrow of the Provisional Government in the October Revolution.

Cover, ‘Trotsky in New York 1917.’ (Courtesy)

In several instances throughout the book, Ackerman documents how the Jewish community played a significant role in Trotsky’s life during his brief stay in the city.

“Many of these Jews in New York knew Trotsky as someone who had outspokenly denounced the Tsar for his anti-Semitism,” says Ackerman. “So he was very popular.”

On the first day Trotsky arrived in New York, he gave an interview to Forverts (The Forward), a Yiddish socialist paper that then had a daily readership of 200,000 — a circulation rivaling that of The New York Times.

The interview turned out to be embarrassing for Trotsky when he couldn’t speak Yiddish with the Jewish reporter. The Bronsteins — for reasons of practicality and commerce — spoke mostly Ukrainian and Russian at the family home growing up.

“Trotsky certainly knew some Yiddish words and phrases from just being around other Jewish people,” says Ackerman. “But he never spoke or wrote in Yiddish in any consistent way.”

“For many years after the Russian Revolution, Trotsky was vilified because of his Jewishness,” Ackerman says. “But he didn’t see it as a major factor.”

Trotsky was born Lev Davidovich Bronstein in October 1879 to a farming family at Yanovka in Kherson province. Then called New Russia, the province now lies in southern Ukraine.

‘Trotsky was vilified because of his Jewishness, but he didn’t see it as a major factor’

Trotsky’s father, David Bronstein, was a dynamic farmer who dragged himself up the social ladder from peasant to wealthy land owner in just a few years. The Bronsteins’ wealth was made possible from a new government scheme during the mid-19th century that saw the emergence of Jewish agricultural colonies in Kherson.

Trotsky always viewed himself first and foremost as a Marxist-cosmopolitan-internationalist, and while he certainly didn’t disown his Jewish background, he made very few references to it throughout his life — most likely because he associated his father’s bourgeois status with his Jewish roots.

Trotsky came to New York via Barcelona on board the Montserrat, with his wife, Natalya and their two sons, Leon and Sergei.

He was expelled from Europe for his radical views, which called for a global Marxist revolution and the overthrow of the existing capitalist world order. Trotsky had also served time in prison in Russia — and escaped — for his revolutionary activities.

While Trotsky was well respected in the small clique of sophisticated Marxist intellectuals around the globe, who knew him from his razor sharp journalistic prose, he was largely unknown by the general public or mainstream press when he arrived in New York in January 1917.

Kenneth Ackerman, author of ‘Trotsky in New York 1917.’ (J. Larry Golfer)

But that anonymity soon faded. By October that year, as one of the leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution, Trotsky became a figure with a global impact.

He founded the Red Army, commanding it with vicious blood-thirsty gusto.

And he was a principal figure in the early years of the Communist International — the October Revolution would transform the course of 20th century history, and Trotsky, along with Lenin, played a prominent role in that transformation.

Those epic events, however, were still a few months away. In New York, between January and March of 1917, Trotsky was still building his reputation as a radical intellectual who posed a threat to the capitalist-global-world-hegemony.

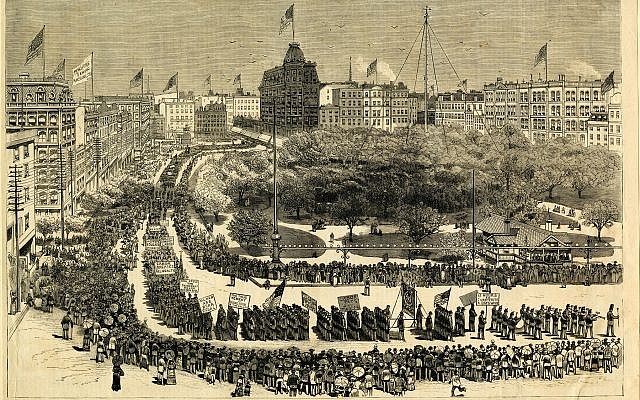

And as Ackerman’s book recalls, until April 1917, the United States had still not entered into World War I. Many Jews and Russian emigres in New York — the most anti-war city in the US at the time — publicly voiced their opposition to America’s involvement. These Jews viewed it as helping the Tsar, who had promoted the anti-Semitism that drove them out of Russia in the first place.

Trotsky was among those figures leading the anti-war protests both in public speeches and in newspaper articles that were printed in the New York Yiddish press. This helped create a period of intense paranoia among the political class, especially against Jews and Eastern Europeans across New York, Ackerman explains.

‘Many of the more radical labor leaders were from Eastern Europe’

“In New York in 1917, there was a huge suspicion of socialists, labor leaders, and outsiders,” he says. “Much of this was fed by the labor movement in America, starting in the 1880s. Many of the more radical labor leaders were from Eastern Europe. Emma Goldman — who was Jewish — was also one of the most prominent anarchists at that time. And she was vilified for her political views.”

The city was famous for its exploitative labor — immigrants made up most of the workers, sweat shops were the norm, and people often worked up to 10 hours straight, hoping to earn maybe a dollar for their efforts.

Consequently, a labor movement began to emerge.

“Jews were very active in radical movements and unions,” says Ackerman. “And as Jewish leaders became more visible, Trotsky became exhibit number one.”

Trotsky’s name thus became associated with two major conspiracy theories.

The first was known as the German Libel — the charge that the Bolshevik Revolution was a mere creature of the German military effort to defeat Russia in WWI.

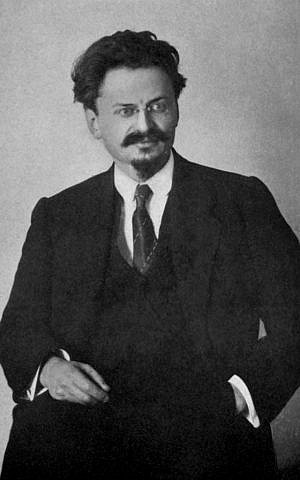

Leon Trotsky (Century Co, NY, 1921 / Wikipedia)

This also stated that Trotsky had received $10,000 from an unidentified German source in the city. Others claimed that if the money had not come from German and socialist immigrants, it potentially could have come from a powerful lobby of Jewish bankers in New York City.

“The second conspiracy theory became known as the Jewish Plot,” Ackerman explains. “The idea was that Jewish bankers paid Trotsky to overthrow the government and create Bolshevism.”

The notion that bankers would finance a radical socialist, whose end goal was to destroy the financial system that gave them extreme wealth in the first place, seems rather preposterous.

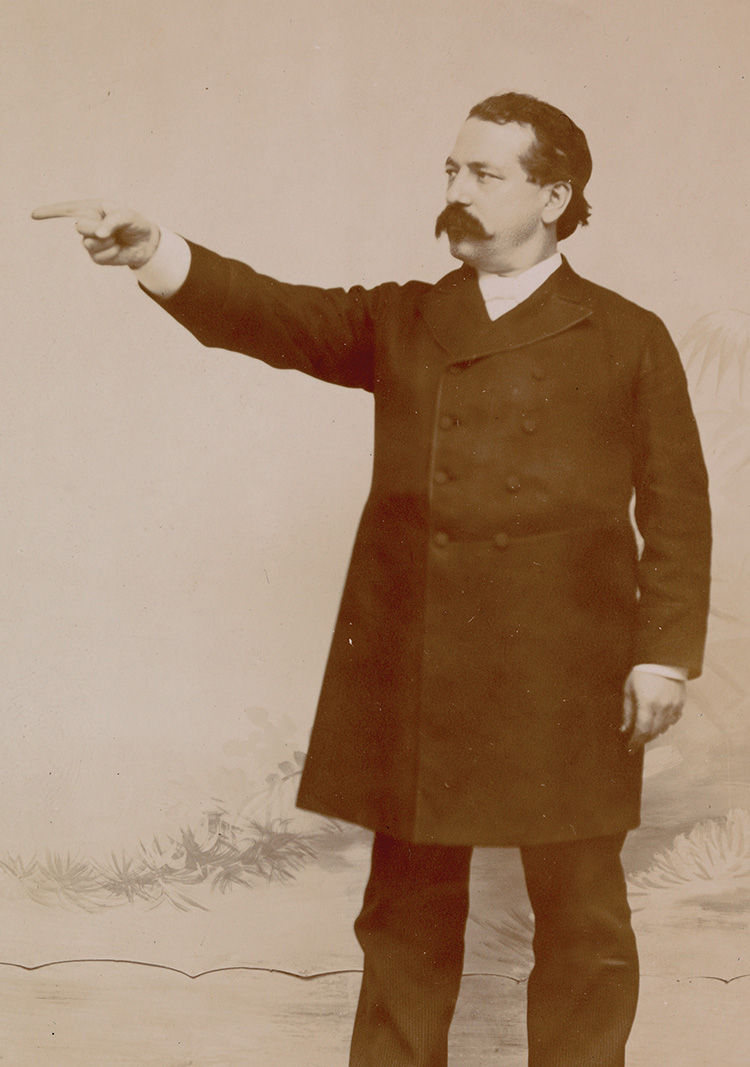

However, as Ackerman’s book explains in some detail, the Trotsky-Jewish conspiracy — in 1917 especially — took a very specific form. It centered on the most conspicuous Jewish financier in New York at the time, Jacob Schiff.

Schiff had openly used his wealth to pressure Russia into changing its anti-Semitic polices. Moreover, Schiff had refused to allow his bank to participate in American war loans to Britain or France as long as they allied themselves with Russia. The suggestion of a link between Schiff and Trotsky came directly from the United States government — specifically, its Military Intelligence Division (MID).

Ackerman’s book cites how MID files from this period are rife with slurs against high-profile New York city Jews like Schiff and others, connecting them to Bolshevik leaders.

Ackerman claims these allegations were coming from individuals who clearly had anti-Semitic agendas.

‘The idea was that Jewish bankers paid Trotsky to overthrow the government and create Bolshevism’

“Trotsky was being tracked by British Intelligence at this time,” says Ackerman, “and several of the people the British had on their payroll were people from Russia with clear track records of anti-Semitism. Including, Boris Brasol, who at the time was circulating copies of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion to American and British Military Intelligence, making the case that Jews were running Bolshevism and posing a threat.”

“Schiff had, of course, contributed to groups advocating the overthrow of the Tsar,” says Ackerman. “But once the Tsar was overthrown, Schiff was aligned with the Kerensky government. So he was not aligned at all with Trotsky or the Bolsheviks.”

But this charge of Jewish bankers backing Trotsky and the Bolsheviks didn’t vanish overnight. According to Ackerman, it became part of the lexicon of anti-Semitism throughout the 1920s and 30s.

“That memo from military intelligence leaked,” says Ackerman, “and it was repeated in many places. It became part of Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda and grew over the years.”

Joseph Stalin in July 1941, the year after he ordered the assassination of Leon Trotsky. (Public domain)

As a result of these various allegations and conspiracies, returning to Russia wasn’t easy for Trotsky. After hearing that Nicholas II had abdicated on March 15, 1917, Trotsky sought to immediately travel back to Russia to stir the fires of revolution.

But he was arrested on his return boat journey by harbor police in Canada. They got a tip off from British Intelligence officers by telegram, just before he boarded a ship in New York, heading back towards Europe. Trotsky would be held as a prisoner of war for a month in Nova Scotia.

Eventually he was released.

It wasn’t long before Trotsky was back in Russia, playing a leading role in the October Revolution.

Today, Trotsky’s name is never far from controversy or debate. Both sides of the political spectrum claim their lineage to him. The far-left see his uncompromising ways as a necessary method for implementing drastic political change with speed and commitment. But so too do neoconservatives on the right.

Looking back at his career, which mythology of Trotsky should we believe?

Was he the psychopathic-blood-thirsty-totalitarian, who believed mass violence and red terror was the ultimate price worth paying for a Marxist utopia? Or was he a humane sophisticated intellectual who —despite his flaws— did believe in ideas like social justice, egalitarianism, and brotherhood of fellow man?

“In the early days of the Russian Revolution, Trotsky put all of the elements in place for the Stalinist dictatorship,” says Ackerman. “He was a strong supporter of war communism, the centralization of power in the Bolshevik Communist Party, and he helped create the secret police, the Cheka. All of these things helped to create a dictatorial-communist-state.”

But in later years, Trotsky began to recognize the evil he helped to construct, Ackerman believes.

Consequently, Stalin had Trotsky murdered in 1940, and tried to erase him from Russian history.

“Love him or loath him, though,” says Ackerman, “Trotsky really was one of the truly consequential figures of the 20th century. By setting in motion the Bolshevik Revolution, he changed the world both for good and for bad.”