It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Friday, January 24, 2020

Damaged Baggage The White Slave Trade & Narcotics Trafficking in the Americas

|

| https://books.google.ca/books?id=l5MtAQAAIAAJ&source=gbs_similarbooks |

KIRKUS REVIEW

Damaged Baggage"" is the underground code name for prostitutes coming across the border with narcotics and it's all part of the gamy expose of The White Slave Trade & Narcotics Trafficking in the Americas. And, according to the author who garnered most of his information first-hand while posing as a travel writer, the traffic is a fast and heavy one, increasing since World War II when a Frenchman called ""Le Duc"" set up a network white slave operation that extended from South America, to Europe, the Middle East and Africa where girls from every nationality were tricked by phony theatrical agents into starting a new life in Argentina and disappeared downhill all the way. Today's recruits generally come from the South American or Mexican slums and Mr. O'Callaghan visits scores of pleasure/leisure palaces from the sophisticated to the pigsty, occasionally having to fight his way out if Madam became suspicious. Unfortunately the book will probably appeal most to her clientele. The author's prose, like the life, is no bed of roses.

Pub Date: March 9th, 1970

Publisher: Roy

Skinheads, Girl Gangs and Satanists: the New English Library Was the Sleazy King of British Pulp Publishing

Punks, mods, Hells Angels and "The Bastard Trilogy" all had their place in the cult 1970s publishing stable.

By Harry Sword

16 December 2014,

The New English Library was the maniacal king of pulp publishing in 1970s Britain. Thrashing out books relentlessly, they excelled in the more brutal end of youth-oriented fiction: rampant gang violence, skinheads marauding around in bovver boots, Satanic cult worship... basically anything that was causing a moral fuss in the decade of disco.

The New English Library was the maniacal king of pulp publishing in 1970s Britain. Thrashing out books relentlessly, they excelled in the more brutal end of youth-oriented fiction: rampant gang violence, skinheads marauding around in bovver boots, Satanic cult worship... basically anything that was causing a moral fuss in the decade of disco.

Formed in 1961 as a subsidiary of the New American Library, they initially published genre fiction – Westerns, sci- fi, mysteries, that kind of thing. However, the editors quickly realised they were missing something of a trick: by gearing books toward a working class youth audience – something American pulp merchants had been doing for some time with great success – they would be all but guaranteed a higher circulation.

Hells Angels, skinheads, punks, mods, girl gangs and bent coppers all found their place in an expanding catalogue that was, by the early-70s, essentially a production line of sleaze. The basic premise was simple: find a youth cult and write about them – and, crucially, to them – including every gritty detail necessary. It proved a winning formula.

Speed was of the essence; this was adrenalised story telling stripped down to the absolute base essentials, as former editor Mark Howell – who worked at the NEL during their early-70s heyday – explained to me.

"That damn delivery schedule was the most driving force I've ever met in publishing," he said. "You just had to get it out there – it was breakneck, insane. I started a series called "Deathlands", and the first writer I gave it to had done a wonderful first story and was given the green light – and spent his entire advance on heroin, which, back in those days, was not unknown. It was crippling for some, but most of our writers were addicts of the typewriter, and one of the glories of this was that it was a conveyer belt – we thoroughly addicted our readers. It was endless repetition stemming from unresolved anomaly.

"Take a book like Forgive the Executioner by Andrew Lane. The hook there was 'Can an agent of the government really kill people with indemnity?' The reaction you want from the reader is: 'Say that again? I don't believe it!' [Adopts solemn newsreader voice] 'I said, "Can an agent of the government really kill people with total and utter indemnity?" 'Say it again?!' [Laughs]You repeat the premise.'

"And, of course, we had a market who were always hungry for more. The James Moffat 'Skinhead' books sold in their millions."

THREE COVERS FROM THE "SKINHEAD" SERIES

Indeed, of the staggering number of books published by the New English Library, it was undoubtedly Moffat's "Skinhead" series (written under one of his many pseudonyms: "Richard Allen") that remains the most iconic. Following misanthropic 16-year-old thug Joe Hawkins through windy football terraces, brutal borstals and peeling Bethnal Green boozers, the series ran to 17 books and drew considerable controversy thanks to its nonchalant approach to a near constant stream of gang violence, racist dialogue, rape and robbery. Moffat himself was often compelled to add disclaimers to the introductions of his books, insisting he was merely "reflecting violent times in the language of the streets".

However, his prose was also peppered with the kind of troubling vitriol you might have seen on a Daily Express front page, ensuring the reader knew precisely which side of the political spectrum he sat on (somewhere between Nigel Farage and Enoch Powell). Nonetheless, the books remain a fascinating and compellingly readable document of the early-70s youthsploitation landscape.

Regardless of his politics, Moffat could really write. Mean spirited and morally bankrupt, his novels spoke of cold rain, futility, bad sex, spilt blood and stale beer, all played out against a backdrop of decrepit East London hinterlands and grey estuary towns.

A prolific writer who was capable of knocking out 10,000 words a day, Moffat's background in writing pulp stories for American newsstand magazines ensured he could turn his hand to almost any subject. He also had literally dozens of pseudonyms – he once wrote a novel entitled Diary of a Female Wrestler under the pen name "Trudi Maxwell", for instance – and was a master of "recycling" his own plots, once stating that you just needed to "change the locations and method of killing".

Mark Howell remembered the impact his books had on an emergent literary counterculture.

"The underground was bursting out, and the NEL was not a mainstream operation; after the 60s we looked for more drama and more realism, and it was the skinheads and the bikers, etc, who provided that. Our writers were using imagination to get there. The British press was such that you could read the Sunday papers and pick up what the youth cults were about, and write about them – and to them – very quickly, provided you had the aptitude. We needed the youth side of it; these weren't essays in sociology, they were attempts at writing adventure novels with new characters and themes. It was very original."

And there lies the rub. Although the format was original, authors like James Moffat and Laurence James (writer of the "Mick Norman" Hells Angels books) had extraordinarily limited firsthand experience of the subjects they covered.

Moffat was a middle aged Canadian who wrote from rural Devon and had never been anywhere near Upton Park. Laurence James – himself an editor at the NEL, as well as one of their star novelists – was a peaceful hippy. Moffat based his books on imagination and rudimentary research gleaned from a few conversations with "local toughs" down the pub. That the books were so convincing is testament to both the energy of the writing and the ability of the writers to get under the hood of their characters.

The 1996 BBC documentary Skinhead Farewell

As an ageing skinhead says in the fascinating 1996 BBC documentary Skinhead Farewell: "I'll keep the books forever. It was my era; it was me and my mates. I'd never sell them. We used to wonder who 'Richard Allen' really was. We thought he had to be involved; he had to have actually been a skinhead or been involved in football violence. The way he wrote... he had to have been in the know – it was just like real life. And even if he wasn't a thug, he thought like one."

Other NEL writers were more thorough in their research methods. GF Newman, for instance, wrote the superbly named "Bastard trilogy" – Sir, You Bastard, You Flash Bastard and You Nice Bastard – which chronicled the misadventures of the corrupt DC Terry Sneed.

Climbing the greasy pole at the Met and patrolling the wilds of early-70s Battersea, Sneed is a borderline sociopath who apathetically sets up grasses, cheats colleagues and batters villains with impunity. Predating "corrupt cop" fiction like Irvine Welsh's Filth or David Peace's "Red Riding Quartet" by some decades, the "Bastard" trilogy has dated remarkably well, and – like so many NEL titles – the originals are highly sought after by collectors today.

"THE BASTARD TRILOGY" BY GF NEWMAN

"I was never heavily involved with the police per se, but I did know detectives and how they operated," explained Newman when I asked about his research. "It was intensely, rampantly corrupt in those days [laughs]. Sometimes I used to go out with them and see what they were up to. And, of course, you got accepted by other policemen as a result of that; they just went ahead and did things as they normally did things – they didn't think, 'Oh, this person is going to write about us.' Most of the things that happen in the Terry Sneed books are based on things that I actually saw and heard – the fiction is in the way that I stitched them together. Almost none of it is invented."

Unlike the "Skinhead" series, the Sneed novels didn't hinge on titillation, right wing propaganda or violence; rather, they sustain a level of taut suspense, painting a vivid picture of the Met as a seedy, closed-ranks boys' club that will do anything to stay afloat, Sneed himself a brilliantly realised anti-hero. The Met in the early 1970s – in all its fetid, unscrupulous and villainous glory – is rendered with such detail that you can practically taste the Embassy Number 1s, rancid Scotch and canteen bacon rolls.

"The detectives would go to pubs and clubs, and that was where it all happened," said Newman. "I lived in Soho at the time – it was far rougher back then. There was a lot of crime on the streets; prostitutes operating out of doorways. There were clubs. A lot of them were unlicensed, and detectives did a lot of work in them. They met informers, grasses, other policemen. They were quite familiar with criminals. It was like a game – they all knew who was doing what, professionally. And they were often taking money from them as well.

"My time at the New English library was great, though. Publishing was fun back then. There was a lot of dope going down in publishing; some of the editors were often stoned in the office, but curiously able to function, as others did on booze. On occasion, James Moffat would turn up at the NEL offices, pissed out of his skull, and run up the stairs to drop off a manuscript and cadge a couple of quid for the taxi, which would be waiting downstairs."

By the late-70s, the NEL was no longer the paperback powerhouse it once was. Moffat was in bad physical shape, suffering the effects of decades of hardcore writing and drinking. New inspiration – in the form of emergent youth cults – was not forthcoming, and one editor had to physically lock him in an office for ten days to deliver a contracted manuscript.

However, while the NEL books formed an indelible mark on the British urban landscape, very few emerge on the second hand market, a sign of how highly regarded they remain today. These books sold in the hundreds of thousands 40 years ago, but are incredibly – legendarily – rare. People held onto them at the time and still do now. For many readers in the 70s, NEL first editions remain as impossible to part with as a lovingly collected box of reggae 7-inches – and the lasting legacy is surely one of the most idiosyncratic stories in cult fiction, as Mark Howell concluded.

"It was a fun experience," he said. "Just imagine it – we were being paid to hang out with these wild boys. But we really did feel that we were contributing to youth culture, and even though it was the seedy side, it was still youth culture. Most of our writers were true believers."

First published November 10, 2016

This is all opinion. Miles: The article below was sent in by a reader. My understanding is that he is from Britain and that he used to be a skinhead of some sort. Not really sure. I think he wanted to be anonymous, but if I have that wrong he can contact me and I will put his name here. I edited it in small ways and added a few comments.

Nov 10, 2016 - Skinheads, Girl Gangs, and Satanists -. The New English Library Was the Sleazy King of British Pulp Publishing. As we find in the article:.

Skinheads

and other

fabricated fascists First published November 10, 2016

This is all opinion. Miles: The article below was sent in by a reader. My understanding is that he is from Britain and that he used to be a skinhead of some sort. Not really sure. I think he wanted to be anonymous, but if I have that wrong he can contact me and I will put his name here. I edited it in small ways and added a few comments.

The Lurid Pulp & Pop Culture Writings of John Harrison

Women Drug Traffickers: Mules, Bosses, and Organized Crime

In the flow of drugs to the United States from Latin America, women have always played key roles as bosses, business partners, money launderers, confidantes, and couriers—work rarely acknowledged. Elaine Carey’s study of women in the drug trade offers a new understanding of this intriguing subject, from women drug smugglers in the early twentieth century to the cartel queens who make news today. Using international diplomatic documents, trial transcripts, medical and public welfare studies, correspondence between drug czars, and prison and hospital records, the author’s research shows that history can be as gripping as a thriller.

Episode 122: The History of Sexual Orientation Conversion Therapy in the U.S.

Host: Christopher Rose, Postdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies

Guest: Chris Babits, Andrew W. Mellon Engaged Scholar Initiative Postdoctoral Fellow

Guest: Chris Babits, Andrew W. Mellon Engaged Scholar Initiative Postdoctoral Fellow

Sexual orientation conversion therapy, the attempt to change one’s sexual orientation through psychological or therapeutic practice, has now been banned in 17 American states and the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, three Canadian provinces, one state in Australia and several nations in Latin America, Europe, and Asia. Beyond the merits of sexual orientation conversion therapy as a medical practice, however, lies a social importance of what the practice represents for a segment of American society.

Today’s guest, Chris Babits, is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Texas at Austin, where he researches the history of the practice and why so many people still support it, even in the face of opposition from medical and psychological professionals.

Audio PlayerWhite Women and the Economy of Slavery

Harrington Fellow at The University of Texas at Austin, 2018-2019

In 1849, sixty-five “ladies of Fayette County” Tennessee wanted their State legislature to know that a central dimension of patriarchy was failing. In a collective petition, they highlighted the ways that this failure was unfolding and how it impacted the lives of Tennessee women, particularly those who were married or who were soon to be wed. At the center of their petition were “thoughtless husbands” who fell far and short of patriarchal ideals. These men, through “dissipation or improvident management,” created circumstances which compelled their new wives to endure lives plagued by “destitution,” “hardship, and suffering.”

The legal doctrine of coverture and the constraints it imposed upon married women were central to the failures of which they spoke. Coverture provided that when a woman married her assets or wages became her husband’s. If she acquired any property after she married, those assets would belong to her husband as well. In other words, the legal doctrine of coverture robbed married women of their independent legal and economic identities.

These sixty-five Fayette County women challenged the tenets of coverture and asked the legislature to consider whether the elements of this legal doctrine were “based on the principle of equity and justice.” They queried whether it was “right and justice to subject the patrimony of married Ladies to the payment of the debts of the husbands which often exist before marriage.” Their line of questioning made it clear that, in their eyes, it was not.

They called upon the legislature to “devise and enact some Law for the State” whereby “the personal estates of females [would] be placed upon a similar basis as their Real estate, and so protected and secured that it cannot be sold, and taken from them without their consent.”

There was a specific reason why they deemed this “placement” necessary: slavery and the region’s dependency upon it. Slave-owning parents typically gave their daughters more slaves than land, and as a result, slaves were profoundly important to women’s personal stability. These women asked the legislature to protect the kind of property that was worth the most to them, because in light of “peculiar Southern institutions, manners, and customs, it [wa]s in most cases a much greater privation and inconvenience to the married ladies to be deprived of their slaves than of their land.”

The petition put forth by these sixty-five “ladies” was exceptional because of its collective nature, but the arguments and circumstances they laid bare in this document echoed those which married slave-owning women voiced in their homes and communities as well as in the individual bills of complaint they filed in nineteenth-century chancery courts throughout the South. In the not-so-private conversations at home and in their petitions, married slave-owning women throughout the South repeatedly made it clear that their husbands were robbing them of their slaves, squandering their assets, and violating what these women believed to be their property rights in enslaved people.

They explained how they came to own the slaves in question—i.e. whether they were inherited, given as gifts, or purchased—as well as the kind of control they exercised over them. They provided documents such as bills of sale, wills, and deeds to support their claims. With striking candor, they informed family, friends, and judges alike that their husbands came to their marriages impoverished and slave-less. It was women, they argued, who owned the slaves in their households, not their husbands. And when it was necessary, they produced witnesses whose testimony substantiated their assertions. One by one, at home and in court, married slave-owning women throughout the South did what the sixty-five women from Fayette County, Tennessee did collectively; they called upon family, friends, and judges throughout the region to help to secure their ownership of slaves and shield their property from their husbands’ ineptitude and misuse.

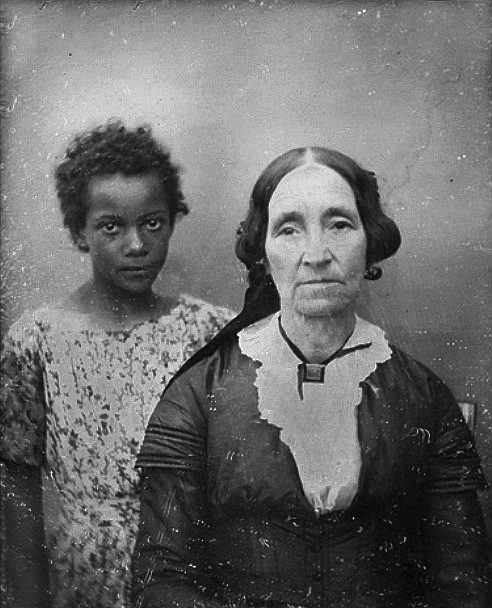

White slave-owning women were not the only ones to insist on their profound economic investments in the institution of slavery; the enslaved people they owned and white members of southern communities did too. The testimony of formerly enslaved people and other narrative sources, legal documents, and financial records dramatically reshape current understandings of white women’s economic relationships to slavery, situating those relationships firmly at the center of nineteenth-century America’s most significant and devastating system of economic exchange. These sources reveal that white parents raised their daughters with particular expectations related to owning slaves and taught them how to be effective slave masters. These lessons played a formative role in how white women conceptualized their personal relationships to human property, imagined the powers that they would possess once they became slave owners in their own right, and shaped their techniques of slave control.

These lifelong processes of indoctrination make it clear why some white women did not feel compelled to relinquish control over their slaves to their spouses once they married, why they sought to manage and “master” their slaves, why they felt completely comfortable buying and selling enslaved people, and why they sued their husbands in court over their slaves, too. The ownership of slaves was gendered: white women slave owners played roles in the trans-regional domestic slave trade and nineteenth-century slave markets. And they responded to the Civil War and adapted to its economic aftermath in the ways that were often different from their husbands, fathers, and brothers.

The Petition of Ladies of Fayette County Tennessee, November 9, 1849, is Document Number: 19-1849-1, Legislative Petitions, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville Tennessee, Accession #: 11484907 Race and Slavery Petitions Project, Series 2, County Court Petitions

The Petition of Ladies of Fayette County Tennessee, November 9, 1849, is Document Number: 19-1849-1, Legislative Petitions, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville Tennessee, Accession #: 11484907 Race and Slavery Petitions Project, Series 2, County Court Petitions

Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South

Books for Further Reading

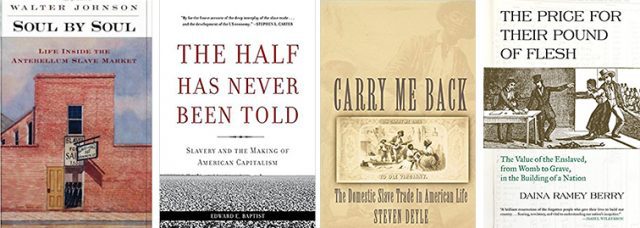

Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (1999) is the most recent and comprehensive study of southern slave markets to date. Johnson examines the interplay between white sellers, buyers, and enslaved people within the context of the slave market and the interstate slave trade.

Steven Deyle, Carry Me Back: The Domestic Slave Trade in American Life (2007) complements Johnson’s study by exploring the ways in which the slave market permeated every town, city, and rural landscape. By doing so, Deyle makes visible how the indifferent calculations of white southerners, and the trauma which these calculations brought about in the lives of enslaved people, occurred far beyond the slave market and often via private sales between members of southern communities.

Edward Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (2016) lays bare the human impact and toll of the slave trade and how the forced migration and labor of enslaved people in the West and Lower South, and the violence white southerners perpetrated against them in order to get them to do that work, proved fundamental to American capitalism.

Daina Ramey Berry, The Price for the Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation (2017) studies the actual human cost of slavery via the prices affixed and values assigned to enslaved people from conception to after death. Ramey Berry’s study also reveals that enslaved people developed their own systems of value that forthrightly challenged those imposed upon them.

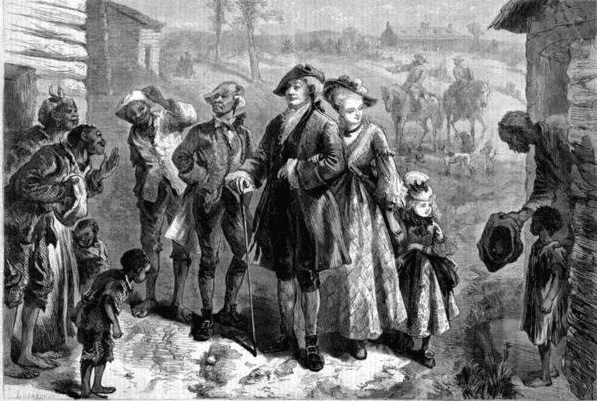

Featured Image: Eastman Johnson, Negro Life at the South (1859). New York Historical Society via Wikimedia (detail)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)