Lectures du Printemps (Sélections)

POST MODERN FASCISM OF THE SO CALLED RIGHT WING TRADITIONALISTS REVIEWED BY A CATHOLIC TRADITIONALIST, BECAUSE YOU CAN'T BE A TRADITIONALIST WITHOUT BEING EITHER CATHOLIC OR ORTHODOX, OF COURSE FOR TRADITIONALISTS LIKE

EVOLA, AND HIS CONTEMPORARY THE MAD POET EZRA POUND THE REVIEWER OUTLINES THE RIGHT WINGS FETISH NOT WITH THE PAST BUT DESTROYING THE MODERN AND THE LEFT WHICH IS MODERNISM ITSELF

Julius Evola (1898 – 1974), The Bow and the Club (in Italian, 1968; English translation by Sergio Knipe, 2018): Julius Evola gained notoriety with his Revolt Against the Modern World (1934), a trenchant book as apposite to the current phase of modernity in the 2020s as it was to the inter-war phase in whose midst it appeared. Men among the Ruins (1953) and Ride the Tiger (1961) carried forward the analyses and conclusions of Revolt. Evola’s authorship looms large, encompassing works major and minor. A late entry in Evola’s bibliography, The Bow and the Club, which perhaps qualifies only as a minor one, anthologizes nineteen independent essays from the 1950s through the 1960s, rewriting them with some cross-references, so as to lend unity to their collocation. “The Psychoanalysis of Skiing” illustrates Evola’s acumen in cultural analysis: Diversion although trivial can testify to the social condition and to the pervasive attitude. Evola remarks the recentness of skiing as a popular sport even while casting doubt on its sportive status. Whereas mountaineering, also recent, requires strength, courage, and skill, skiing, in Evola’s view, simply makes use of gravity. One emphasizes the ascent – the other the descent. The skier must, of course, ascend before he descends, but “the problem has been solved by building cableways, chair lifts, and sledge lifts that meet the real interest of skiers by effortlessly taking them up.” The very mechanization of skiing ranks it, as Evola writes, “among those [activities] most devoid of any relation to the symbols of the previous world-view.” Evola detects in skiing an essential passivity. The thrill of the downhill run reflects the general “collapse and downfall” of the modern world, to which the skier gleefully submits. Evola relates skiing to “naturism,” his word for nudism. A demon of shamelessness indeed hovers over the piste. The notorious hot-tubs of the Sierra-Nevada ski lodges, although they post-date Evola’s death, affirm his intuition.

The essay on “Subliminal Influences and Intelligent Stupidity” again explores the condition of spiritual non-being. In a modern context, propaganda and advertising resemble gravity. They exert an omnipresent pull that pulls down most people. The program of ceaseless indoctrination perpetrated by the Left, and always by the Left, takes its most basic form, Evola asserts, in the fetishization of words. Some words acquire the status of totems and others of taboos. Words like democracy, socialism, work, sociality, and social justice belong in the totem category, functioning as praise; words like reaction, obscurantism, immobility, and paternalism belong in the taboo category, functioning as vilification. Evola insists on the duplicity of the epithet reaction, which the Left transforms into “a synonym for abomination – as if, when certain parties ‘act,’ others should refrain from reacting and instead turn the other cheek like good Christians.” The Left’s appropriation of the French engagé likewise irritates Evola: “The implication is that anyone who is not a leftist is not ‘engagé’ as a writer, intellectual, or man of action, but is rather frivolous, superficial, irresolute, lacking in vigour, and with no real cause to defend.” In fact, “the only truly ‘engagé’ person is he who defends those higher ideals and transcendent aims that the leftist rabble… covers with contempt and disrepute.” The Big-Sisterish gutting of language fosters “intelligent stupidity,” which ensconces itself in journalism and education. Journalists and educators assume a posture of “nonconformism,” while conforming utterly to the institutional consensus. Evola reserves his bitterest bile for criticism, a word that he isolates sanitarily in quotation marks. “Generally speaking, ‘criticism’ should be seen as one of the scourges of modern culture.” “Criticism” pretends to judge a legacy of the past that it could not, itself, create, which inspires its envy, and which it would excise. Anyone who has any contact whatsoever with the professoriate will know precisely what Evola means.

“The Youth, the Beats, and Right-Wing Anarchists” refers to an earlier item in the sequence of The Bow and the Club, “The Negrification of America.” In Evola’s estimate, the United States of America served as an early indicator for the degeneration of the West. Besotted by the notion of democracy, a term that appears nowhere in the Constitution, wholly de-spiritualized, attracted because of the absence of refinement and nobility to debasement and vulgarity, America pioneered the jejuneness of total commercialization. When the loss of high culture deprived people of a healthy orientation at the first degree, the non-nourishing character of low culture provoked confusion at the second degree. Social phenomena like the Beatniks and Hipsters represent that second degree of mental befoggedness. The subject vaguely guesses that something has gone lacking, not only in society, but in himself, but he cannot discern what. The Beatniks and Hipsters instinctively reject society, but they seek asylum in libertinism rather than in discipline. They naively buy into Leftist and non-Western tropes because these settle on their perplexity the ornamentation of intellectuality, but they nevertheless gravitate to the sensual and the orgiastic. “There are reasons to believe,” Evola writes of the Beatnik’s alienated musical predilections, “that the identification with frenzied and elementary rhythms produces forms of ‘downward self-transcendence’ [and] forms of sub-personal regression to what is merely vital and primitive.” Evola contrasts the American Beatniks and Hipsters with a portion of Italian youth, “who are rebelling against the socio-political situation in Italy while, at the same time, showing an interest in… the world of Tradition.” One knows of the college-age Italian Marxists who agitated against social norms in the 1960s, as they did in France and elsewhere in Europe. They culminated in the Red Brigades. The Young Traditionalists to whom Evola refers seem to have disappeared without a trace. They certainly have no counterpart in Twenty-First Century North America. Whereas Beatnikism went extinct with Maynard G. Krebs, Hipsterism has risen zombie-like from the grave, taking as its new milieu the foetid soil of the Great Awokening.

Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900 – 2002), The Relevance of the Beautiful and Other Essays (in German, 1967 & 1977; English translation by Nicholas Walker, 1986): Hans-Georg Gadamer while not so much as Evola, who claimed for himself the title, conforms to the pattern of a Traditionalist. He insisted on the relevance of Western Civilization’s classical foundation to its modern phase – and he recognized the distortions in that modern phase. Gadamer lived through the same events, after all, as Evola, but his rhetorical approach differs from that of the Italian, being less polemical and more dedicated to finding ways in which some portion of modernity might be assimilated to the classical episteme and thus redeemed. The essays on beauty that Relevance brings together serve Gadamer’s agenda. In the title-essay, Gadamer investigates art, the creative expression of beauty, through the concepts of play, symbol, and festival. Introducing the essay, Gadamer rehearses the history of aesthetics beginning with Plato and including Immanuel Kant, G. W. F. Hegel, the Romantics, and the Twentieth-Century justifications of non-representational painting and non-tonal music. Gadamer validates Plato for insisting on beauty’s transcendence, but he regards Plato and Kant as defining beauty in too static a way. Gadamer credits Hegel for remarking the historicity hence also the temporality of art. The appreciation of beauty has for Gadamer an inherent memoriousness, by whose invocation he rescues the Platonic anamnesis into his own theory despite his criticism of staticity. While “the beautiful fulfills itself in a kind of self-determination and enjoys its own self-representation,” it also reminds its witnesses of a truth that they once knew but tend to forget. Beauty in art is self-determining because it is play. In play, reason “sets the rules” for “non-purposive” yet meaningful activity. Beauty in art is symbolic because it is anamnetic. Gadamer restores the etymon of the term “symbol”: The tessera hospitalis or symbolon by means of which host and guest after a temporal hiatus ritually recognize one another. Beauty in art corresponds to the festive because its special time, as imbued with the sacred, lies outside profane time and because it is communal. “A festival,” Gadamer writes, “is an experience of community and represents the community in its perfect form.”

Lest elements of the foregoing appear contradictory, for Gadamer the beauty of art exists in time and yet reserves its essence outside time. The problem of modern art beguiles Gadamer because he can see that the sedition of non-representational painting and non-tonal music consists in a narcissistic rejection of the past arising from the intimidating awe of excellence in its persistence. The modern artist reacts against the communion inherent in producing the tessera hospitalis. He rejects the host-guest bond and refuses the festive occasion, in which, as in gift-giving, society obliges everyone to participate. In the classical or medieval festum, moreover, not only does the living community come together, but the spirits of dead make themselves known too. In disdaining tradition, which the ancestors gift upon the present and which festivity celebrates, a self-conscious (but is that the word?) modernity commits the sacrilege of scorning the dead. Such scorn violates the ethical unity of past and present on the basis of which, through memory, consciousness arises and endures. In the essay that follows “The Relevance of the Beautiful,” Gadamer returns to the topic of festivity. “The Festive Character of Theater” owes something to arguments that classicist Jane Harrison makes in her Ancient Art and Ritual (1913), which emphasizes not only the sacred origins of drama, but of all artistic genres. “A festive occasion,” Gadamer writes, “is always something uplifting which raises the participants out of their everyday existence and elevates them into… universal communion.” Festivals have a theurgic quality, such that “all cultic ceremony is… creation.” The typical modern drama, aiming not at communion but at alienation, displays the same willful disrelation to the past as non-representational painting and non-tonal music.

Gadamer believed it possible to overcome modernity’s self-isolation in novelty-for-its-own-sake or in ugliness as the substitute for beauty. In 1967 or 77 such a prospect might have loomed above the horizon. In the age of the Dead White Male, of pulling down statues and veiling portraits, that prospect has retreated out of sight. The “cutting edge” has everywhere revealed itself as the homicidal metaphor that it always was. But because of his bright view, Gadamer continues to beckon – all the more so – due precisely to the onset of a new Götterdämmerung. Take the essay on “Aesthetic and Religious Experience” where he concerns himself with the tenacious unity of “the eminent text” in poetry and theology. Gadamer’s “eminent text” consists in writing that functions other than as a representation of oral utterance and that claims truth and invites faith. He gives the example of Hesiod’s Theogony. Hesiod’s poem can only be apprehended through the readerly eye, with much back-scanning; not through the ear. In Hesiod’s proem, reporting the encounter with the muses that impelled his bardic career, those deities affirm that they can convey both truth and falsehood. How then to assess Hesiod’s purportedly truthful validation of Olympian order? One must measure the likelihood of the tale, judge the coherence of its details, and choose. Religion penetrated all ancient activity, poetry included. The modern arts separate themselves from religion, even radically. Gadamer writes that, “This does not mean that religious content ceases to be communicated through poetry… Nor does it mean that religious texts cannot have a poetic-literary aspect that marks them off from other religious texts.” He cites “passages in the New Testament with a densely wrought narrative quality,” a textual eminence that gives a sign to the attentive subject. Gadamer nevertheless concedes that under “the radicality of the Enlightenment… religion itself is declared to be redundant and [is] denounced as an act of betrayal or self-betrayal.”

Nicolas Slonimsky (1894 – 1995), Lexicon of Musical Invective – Critical Assaults on Composers since Beethoven’s Time (1953): Nicolas Slonimsky, St. Petersburg born, became an émigré to the U.S.A. in the aftermath of the Bolshevik insurrection in Russia. Admitted to the St. Petersburg Conservatory before adolescence, having been examined by none other than its director Alexander Glazunov, Slonimsky looked forward to a life in Russian high-musical tradition as a keyboard virtuoso and dirigent. Instead, in gigs in New York, Massachusetts, and California, he became the preeminent musicologist of his era, a conductor of avant-garde compositions by Charles Ives, Edgar Varèse, Henry Cowell, and others, a writer, raconteur, humorist, lecturer, and to all who knew him, a man of extraordinary geniality and magnanimity. For five decades he wrote and edited the successive editions of Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Composers and Musicians, a monumental task. His Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns (1947) inspired many a composer, not least the eccentric Frank Zappa, who became a close friend. In his Lexicon, Slonimsky, by dint of assiduous research in newspaper morgues, compiles an encyclopedia of cutting and acidulous words penned by critics in their responses to new compositions beginning with those of Ludwig van Beethoven in the early Nineteenth Century. Slonimsky prefaces his assemblage with a brilliant essay on “The Non-Acceptance of the Unfamiliar.” Slonimsky reveals his main criterion of selection in the opening paragraphs of his Introduction: “The music critics whose extraordinary outpourings are detailed here are not necessarily opinionated detractors,” but “many of them are men of great culture, writers of brilliant prose, who, when the spirit moves them, excel in the art of imaginative vituperation.” Indeed, Slonimsky regrets a decline in “imaginative vituperation,” the rhetorical virtuosity of which he relishes. When, after a lengthy series of taped interviews, a diffident young man proffered him a copy of the Lexicon to sign, he wrote: “For Tom Bertonneau, with best wishes for more and better invectives – Los Angeles, March 25, 1977.”

Beethoven’s first auditors, inculcated musically in the Eighteenth-Century formalities of “Papa” Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, experienced much difficulty in according themselves to an enlarged compositional scheme and, as it seemed to them, harmonic aberrations. Writing in Der Freimütige, Vienna, September 11, 1806, August von Kotzebue reported that, “Recently there was given the overture to Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, and all impartial musicians and music lovers were in perfect agreement that never was anything as incoherent, shrill, chaotic, and ear-splitting produced in music.” In the Harmonicon, London, July 1825, an anonymous reviewer described the Ninth Symphony as “a composition in which the author has indulged in a great deal of disagreeable eccentricity.” The reviewer declared of the symphony that, “we cannot yet discover any design in it.” A column in Musical World, London, March 1836, comments without specifying the work: “Beethoven mystified his passages by a new treatment of the resolution of chords, which can only be described in words by the term, ‘resolution by ellipsis,’ or the omission of the chord upon which the discordant notes should descend.” Johannes Brahms fared little better with his first audiences. According to the Boston Evening Transcript, January 4, 1878, “In Brahms’ First Symphony there appears to be a large quantity of mere surplusage, a strenuous iteration and reiteration, after the manner of one who is unable to utter his thought once and for all.” On February 25, 1904, writing in the Boston Daily Advertiser, Louis Elson wrote of Claude Debussy’s Afternoon of a Faun that, “The faun must have had a terrible afternoon, for the poor beast brayed on muted horns and whinnied on flutes, and avoided all trace of soothing melody, until the audience began to share his sorrows.”

Slonimsky points out in his Introduction that ill-disposed music-journalists like to invoke the Chinese language or the caterwauling of felines in heat to characterize music that falls chidingly on their ears. In 1910 the critic H. T. Finck condemned one of Richard Strauss’s tone poems, by charging that, “Strauss lets loose an orchestral riot that suggests a murder scene in a Chinese theater.” A musical Philadelphian with strong prejudices denounced Arnold Schoenberg’s Violin Concerto (1936) as assaulting his ears like “a lecture on the fourth dimension delivered in Chinese.” As Slonimsky writes, “the Mozart-loving Oulibicheff heard ‘odious meowing’ and ‘discords acute enough to split the ear’ in [Beethoven’s] Fifth Symphony.” Slonimsky devotes long sections to Schoenberg, Alban Berg, Anton Webern, and Igor Stravinsky. The seventy years since the first publication of the Lexicon fail to uphold the universal applicability of its author’s thesis that the ear invariably catches up with the score. While the Viennese trio still have advocates, mostly in the academy, the musical public has not done for them what it eventually did for Beethoven, Brahms, Strauss, and Mahler. Stravinsky, in whose early period the extravagances of the Russian folkloristic style effloresce, differentiates himself from his Teutonic contemporaries. His Firebird (1910), Petroushka (1911), and Rite of Spring (1913) will draw contemporary audiences although in their day they drew mostly contumely, an example of which explains Slonimsky’s delectation in Schimpf. In the Boston Herald, February 9, 1924, after a performance of the Rite, these verses appeared:

Who wrote this fiendish Rite of Spring,

What right had he to write the thing,

Against our helpless ears to fling

Its crash, clash, cling, clang, bing, bang, bing?”

After an intervening quatrain, the versifier concluded with this couplet:

He who could write the Rite of Spring,

If I be right, by right should swing!

A useful “Invecticon” follows the sample reviews, with such entries as “Broken China,” “Epileptic Convulsions,” “Tipsy Chimpanzee,” and “Volcano Hell.” Each entry sends the reader to the pertinent composer or composers.

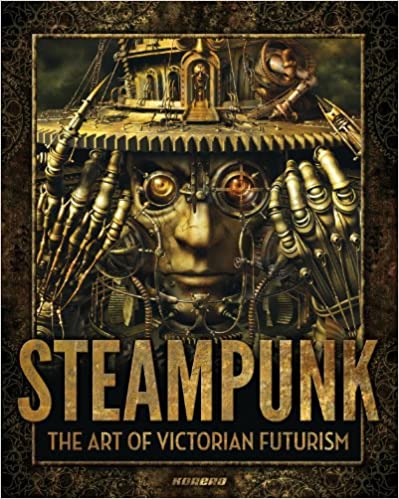

Jay Strongman (birth date nowhere listed – but a good guess, mid-1950s): Steampunk – The Art of Victorian Futurism (2011): Wikipedia having omitted to dedicate a page to “Jay Strongman,” difficulty attends the attempt to identify him – to discern, for example, when he was born or where he currently domiciles. Various websites ascribe to him a career as a “DJ,” or disc-jockey, but whether on radio or in discotheques remains unclear. “Strongman” has authored at least one book, the title under discussion here. The counter-cultural eccentricity known as Steampunk offers itself as less fugacious than the man who writes about it. It goes back proximately to a set of genre novels of the 1970s and 80s. Michael Moorcock’s The Warlord of the Air (1971), The Land Leviathan (1974), The Steel Tsar (1981) take place in a retro-world of the early Twentieth Century where the steam technology of the Victorian and Edwardian Ages have perfected themselves, thereby preempting the emergence of the proper electrical and internal-combustion technology of the Twentieth Century. In The Warlord of the Air, for example, the British Empire dominates the world not by its ocean-going Royal Navy, but domination of the airways using armed dirigible airships. William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s Difference Engine (1990) assumes a similar milieu. But to assert that these writers conjured Steampunk out of the blue is not quite accurate. They wrote on the basis of two authorships, that of Jules Verne and that of H. G. Wells, that extrapolated existing technology into its then future development and application. Verne’s 20,000 Leagues under the Sea (1869) and Wells’ War in the Air (1906), with their submarine vessel and War Zeppelins respectively, established a template for Moorcock and Gibson-Sterling to exploit. Steampunk consolidated itself under that name, however, decades after the appearance of The Warlord of the Air and The Difference Engine. Steampunk emerged as a subdivision of the “cosplay” or costume-play associated with comic book conventions in the late 1990s. The color and structure of Victorian and Edwardian attire makes a good antidote to the blandness of modern dress.

Strongman acknowledges the motivating nostalgia of Steampunk. “Like Neo-Victorianism, which preceded and then paralleled it,” Strongman writes, “Steampunk is… a form of escapism – a yearning for a simpler time, a period in which there was little doubt that the future, with technology’s help, was going to get better and brighter.” Strongman adds how “there is also a longing for an age in which machines were awe-inspiring steam-powered engines and magnificent clockwork mechanisms of gleaming brass, polished wood and shining steel – so unlike today’s bland boxes of micro-chips, grey plastic and hidden, integrated circuits.” The devices and the attire go together. They suggest a concern for formality and a fondness for ornamental detail that lifts things to a higher level. Strongman discovers another origin of Steampunk when he points out that, “The dapper Edwardian gentleman was… the inspiration for the bowler-hatted John Steed in the innovative TV detective series The Avengers, which ran from 1962 until 1969.” Haberdashery and engines came into prominent display in films such as The Wild Wild West (1999), derived from the 1960s television series; and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003), by which time the moniker Steampunk had organized itself. Strongman focuses The Art of Victorian Futurism on painting, illustration, sculpture, collages, and assemblies by contemporary craftsmen and creators. The imagery of Japanese illustrator Kazuhiko Nakamura (born 1961) both typifies and accentuates the Steampunk vision. Nakamura emphasizes the dystopian side of Steampunk that first presented itself in Gibson and Sterling’s novels. Paul Guinan (birth-date nowhere listed – but a good guess, mid-1950s) injects humor and irony into his Boilerplate franchise. Boilerplate is a steam-powered robot who undertakes adventures in the years around 1900. He joins Teddy Roosevelt, for example, during the Cuban expedition.

One might recall Evola’s implied thesis in the essays of The Bow and the Club that even the trivial can produce a sign of the times. Steampunk certainly ranks as a diversion, but its particular focus on the Victorians and Edwardians distinguishes it from purely contemporary fads. The period from 1850 to 1914 was, after all, the period of the intact family, the paterfamilias, monarchy, sensible limitations on suffrage, and a pervasive sexual modesty, at least in the middle and upper classes. The people of those eras did not suffer from the delusion that everyone should attend college, but they knew the value of training and apprenticeship. That age honored people who acquired mechanical skills, like those who designed, built, maintained, and drove the great steam locomotives and the impressive ocean liners and dreadnaughts of late-Nineteenth Century travel, commerce, and national sovereignty. The steam locomotive still exerts its fascination on many people. In cities and towns across the continental U.S.A., when a steam locomotive, restored to operation, makes an appearance at the local, mostly disused railroad station, crowds will turn out. The locomotive will be pulling a suite of passenger cars, their original appointments meticulously refurbished. Unlike the diesel-electric freight-puller, the steamer possesses dignity. The cars of its passenger train will not be covered by obnoxious, gang-related graffiti, as are the ugly boxcars and tankers of the freight assembly. Fathers will bring their school-age sons to see the steamer. The event will exhibit the characteristics of a festival. It is highly unlikely that a gaggle of feminists will be among the onlookers. Hipsters, Greens, and the other members of the phony heterogeneity have other things to do.

[I dedicate the dozen foregoing paragraphs to my friends, the parents and children of the Flanders family.]