Op-Ed: Anti-apartheid divestment built a movement of people. That’s what the climate crisis needs

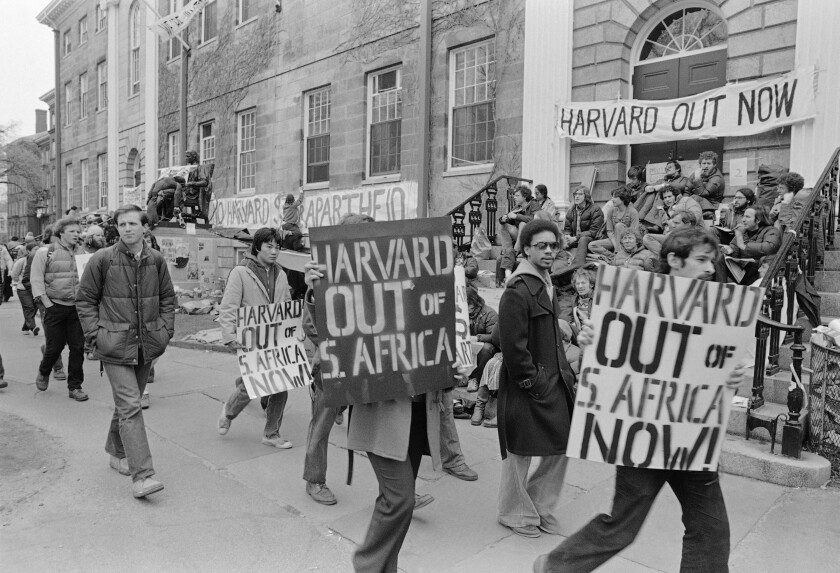

Demonstrators march at Harvard in 1978 against the Harvard Corp.'s refusal to divest from stocks in companies operating in South Africa.

(MSG)

BY ZEB LARSONFEB. 13, 2022 3 AM PT

The environmental activist and writer Bill McKibben estimates that the movement to pressure institutions to stop investing in and profiting from carbon-emitting industries has resulted in institutions pledging to pull $15 trillion in investments from polluting companies.

That’s an incredible achievement in just one decade. However, climate divestment’s increasing visibility has also cultivated an audience of detractors. Some opponents claim that divestment cannot meaningfully change the demand for fossil fuels — and in fact, lowering share prices can make those companies attractive to less ethical investors. Going a step further, such critics claim that divestment’s economic harm to companies has always been minimal — even in apartheid-era South Africa, where divestment as a tactic was born.

But measuring divestment’s success solely on its financial impacts is a mistake. Divestment’s true power is the ability to change minds and mobilize action, with effects that reach far beyond targeted investors and companies.

What happened in South Africa shows why. From 1960 through the 1980s, anti-apartheid activists were unable to persuade governments to push back against South Africa’s oppressive racial laws. American presidents, for example, were loath to act because South Africa was an important ally and regional policeman during the Cold War. And so activists in the United States and elsewhere turned to divestment to undermine apartheid, refusing to invest in companies that did business in South Africa.

But divestment was not seen as a way to hurt the South African economy, or even to punish U.S. companies. In 1966, minister and activist George M. Houser, who helped found the American Committee on Africa (ACOA), a group dedicated to opposing colonialism in Africa, wrote a strategy paper advocating what he called “disengagement”— both withdrawing existing investments and prohibiting new ones.

Anti-apartheid protesters block building entrances at UC Berkeley in 1986.

(Catharine Krueger / Associated Press)

At the time, ACOA was working with other groups to boycott Chase Bank (then known as Chase Manhattan Bank) because of its policy of lending to South Africa. “This campaign is not based upon the thesis that even if all of the economic power of the United States was brought to bear … the architects of apartheid would feel they had to accept new policies,” wrote Houser. Rather, he argued that disengagement “would materially affect the outlook of many other powerful countries.” Houser’s model was the strategy that became divestment and, in many ways, continues to guide the movement today.

Initially, the tactic targeted specific companies and financial institutions engaging in high-profile projects in South Africa. Polaroid was targeted in 1970 for selling photographic equipment used to produce the hated passbooks that helped control the movement of people in South Africa. Then, in the mid-1970s, activists began to pressure city and state governments to remove investments from companies working in South Africa.

Divestment gained steam with small victories at Hampshire College in 1977 and the University of Wisconsin in 1978. Within a decade, as companies found themselves constantly under criticism for their presence in South Africa, divestments multiplied and some companies withdrew.

But beyond these material effects, divestment had one huge effect that even Houser might not have fully foreseen: It helped build a truly national anti-apartheid movement in the United States. Up until divestment, the anti-apartheid movement in the U.S. saw limited success. Although ACOA was technically a national committee, it was primarily a New York institution. Consumer boycotts of imported South African goods, such as platinum, could often be difficult to sustain. And as long as South Africa dodged the news cycle, it took the wind out of organizing sails. But divestment broke through. Where Houser was hoping to sway other countries into supporting sanctions, the strategy worked on American hearts and minds.

What made divestment different, and ultimately so popular? Some of it was moral appeal. It’s no coincidence that the movement gained strength quickly in churches and on college campuses: Whether or not you could stop apartheid, profiting from it was immoral. Part of it, too, was political. Activists had great success reminding Americans that even as U.S. companies were shedding manufacturing jobs, they were hypocritically taking advantage of cheap labor in South Africa.

A rally in support of fossil-fuel divestment outside San Francisco City Hall in 2013.

(Jeff Chiu / Associated Press)

But even more successful was the way that divestment created opportunities for action: In the words of activist Cherri Waters, “movements need something for people to do.” Divestment created tangible targets for people to organize around and against that were also specific to where they lived: university pension boards, church investment boards and local governments. Lobbying these organizations was effective and helped the movement to spread across the country.

This widespread activation led many Republicans to endorse sanctions against South Africa against the wishes of President Reagan. Richard G. Lugar, a prominent Republican senator from Indiana, began supporting sanctions after complaining that he couldn’t go to his kids’ baseball games without constituents asking him what he was going to do about apartheid. The pressure to do something became overwhelming enough that Congress authorized sanctions against South Africa in 1986.

The critics are right, in a way: Apartheid-era divestment’s economic impact on companies was small. Lowered U.S. share prices on their own were not economically damaging to South Africa. Even the withdrawal of businesses was largely a blow to South African morale only.

But that doesn’t undercut its importance as a strategy. By increasing awareness of apartheid and the U.S. role in sustaining it, divestment activated a core of people who would support other actions against apartheid. Stigmatizing companies and lowering investor confidence are important, but the tactic’s primary advantage is that it organizes people, gives them an action to accomplish and leaves them open to pushing for even more substantive change.

Against climate change — a nonhuman target that lacks the same sheer evil that undergirded apartheid — this approach is all the more critical. Whether it affects the bottom line or not, building a movement of people is what matters.

Zeb Larson is a writer and historian whose research has focused on the anti-apartheid movement. This article was produced in partnership with Zócalo Public Square.