It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Monday, March 07, 2022

Sun, March 6, 2022

By Yuka Obayashi, Maki Shiraki and Yoshifumi Takemoto

TOKYO, March 7 (Reuters) - Japanese firms are under deepening pressure over their ties to Russia and are scrambling to assess their operations, company and government insiders say, after Western rivals halted businesses and condemned Moscow for invading Ukraine.

While environmental, social and governance (ESG) investors have previously targeted Japan Inc for use fossil fuels, scrutiny over Russia could become intense. Executives say privately they are worried about reputational damage, a sign corporate Japan is - however reluctantly - becoming more responsive to pressure on social issues.

Japan's trading houses, commodities giants long seen as quasi-governmental arms integral to Japan's energy supply, have big ties to Russia. Last year Russia was Japan's second-biggest supplier of thermal coal and its fifth-largest of both crude oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG).

"The energy issue has implications for national and public interest, so it has to be discussed properly with the government," said one trading house insider, who like others spoke on condition of anonymity.

"But we also have to think about our corporate value and about how we explain this to our shareholders. It's a difficult position."

Mitsui & Co and Mitsubishi Corp have stakes in the giant Sakhalin-2 LNG project Shell is now exiting. Itochu Corp and Marubeni Corp have invested in the Sakhalin-1 oil project that Exxon Mobil is pulling out of.

Mitsui and Mitsubishi said they would consider the situation, together with the Japanese government and partners. Itochu and Marubeni declined to comment on their plans related to Sakhalin-1.

Japanese firms have largely said they are watching the situation. Those that have halted activity have tended to cite supply-chain disruption rather than human rights.

A senior executive at an automaker said management at his company was holding daily meetings to gauge the impact of financial sanctions and the implication for parts supply.

"We're also discussing reputational risk and how to deal with the news from the point of view of human rights and ESG - of course we're aware of that," said the executive.

"But we can't just immediately decide we're going to pull out because we can't tell how long the Ukraine crisis will continue."

Japanese firms typically do not face the same level of scrutiny from shareholders, customers, regulators and even their own employees that Western companies now confront, said Jana Jevcakova, the international head of ESG at shareholder services firm Morrow Sodali.

"Most Japanese companies still don't have a majority of international institutional investors. Those that do will very shortly, or already are, feel the pressure."

RELIANT ON RUSSIA

A manufacturing executive said his company felt a responsibility to local staff in Russia but was also concerned about the risk of saying nothing.

"Japanese companies have been slow to react. Too slow. And I can't agree with that," he said. "If we keep quiet and just continue manufacturing and selling, we will likely face a risk to our reputation."

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has unveiled steps to help cushion the blow from higher oil prices, but it is unclear what the government will do about broader dependence on Russia. Japan's imports from Russia totalled around $11 billion in 2020.

Government officials say privately Japan cannot just walk away from Russian energy, even as they acknowledge the peril.

"If Japan remains invested in Russia, that itself runs the risk of drawing criticism" should the conflict be prolonged, said an official close to Kishida.

In a moment of rare outspokenness for the leader of a state-owned lender, the head of the Japan Bank for International Cooperation said last week that "it would not be right" for companies to stick to business as usual in Russia. Toyota Motor Corp and Nissan Motor Co have stopped exports to Russia, citing logistics issues, with Toyota halting local production.

Nissan, Mazda Motor Corp and Mitsubishi Motors Corp are all likely to stop local production when parts inventories run out, they say.

Japan's most prominent companies will likely feel more heat as Western investors themselves pare back ties to Russia.

"We believe good corporate citizenship includes support of governmental sanctions, as well as closing down activities that might fall outside the current sanctions," said Anders Schelde, chief investment officer at Danish pension fund AkademikerPension, which has $21.3 billion of assets under management and $342 million exposure to Japanese equities.

"From a financial point of view this might mean companies suffer short-term losses, but given the long-term stigmatisation of Russia that is likely, the long-term cost will not change much." (Reporting by Yoshifumi Takemoto, Yuka Obayashi and Maki Shiraki; Additional reporting by Nobuhiro Kubo and David Dolan; Editing by William Mallard)

Cries of pain and anguish — why the ANC is on the wrong side of history over Ukraine

Nicholas Rutherford (23) from Johannesburg demonstrates in front of the Russian Embassy in Pretoria on 3 March 2022 with the group Picket for Peace against the war in Ukraine. The Sunflower is Ukraine's national flower.

By Ray Hartley and Greg Mills

06 Mar 2022

The ANC, having returned to its Russian lodestar, faces a second rude awakening. This time it is not the Berlin Wall falling, so much as the free world erecting a wall of isolation around Russia — a Berlin Wall in reverse, this time insulating the West against Putin’s excesses.

Thirty-five countries voted to abstain in the recent United Nations vote condemning the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Five predictably voted against: Russia, Syria, Eritrea, Belarus and North Korea. Of the remainder, 141 voted to adopt the resolution with the demand for the Russian Federation to cease all military activity in Ukraine and withdraw its forces.

South Africa was among a minority (17) of African countries that abstained, with 28 African countries voting in favour of the resolution. The Department of International Relations and Cooperation had issued a statement that seemed to reflect the country’s place in the democratic world when it called on Russia to withdraw. But this statement was rolled back and the decision to abstain was made. Why was this the case?

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin may have thought that the invasion would go quickly, the Ukrainian leadership would immediately capitulate and flee and that he would force the Europeans to accept his will

Such a scenario would have allowed him to quickly cement the narrative he was peddling that he was embarking on a “special operation” to secure the contested regions of Donbas, and the world would probably have disapproved but moved on as it did when he annexed Crimea in 2014.

But things didn’t go his way. Meeting fierce, organised resistance he became bogged down and began resorting to the Russian tactics used in Chechnya, of bombarding civilians into submission. The images of the terror unleashed on Ukrainian cities and of the hundreds of thousands who fled to neighbouring countries quickly turned the narrative against Putin.

It became apparent that the Ukrainians were going to stay and fight it out, and that Europe — led by the countries that abut Ukraine — had found its spine. Even if there was an asymmetry of military capabilities (in favour of Russia), there was an asymmetry of will (in favour of President Volodymyr Zelensky’s Ukraine). It could no longer be denied that Putin was using military force to undermine a sovereign, democratic country and the world responded with an unprecedented campaign of financial, industrial, cultural and sporting isolation.

Putin, it was clear, was on the wrong side of history.

It was clear that the free world — countries where democracy and sovereignty were cherished — stood against Putin’s aggression and the reasons for voting in favour of the UN resolution calling on him to cease prosecuting the war were many. Among them:

Putin had clearly broken international law and invaded a neighbouring state. This is a bad precedent, especially in Africa where colonialism has left a legacy of contested borders.

Unless Putin withdraws, there will be ongoing conflict in Ukraine for many years, with the potential to spill over into other parts of Europe.

Human rights have clearly been abused, with well-documented attacks on civilian homes, schools, universities and public squares using cluster munitions, missiles and artillery.

There is a need to put pressure, not reduce it, to achieve negotiations, just as was done in South Africa in the 1970s and 1980s.

Ukraine is a democracy; Russia is not.

Yet, despite all of this, South Africa, a democratic country that favours peace and believes in the sovereignty of nations, chose to abstain. The answer lies in the ANC’s historical relationship with Russia.

When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and the Soviet Union was dissolved over the next several years, the ANC and the SA Communist Party were deeply affected. For decades the Soviet Union had supported liberation movements such as the ANC with education, military training and political support.

The Soviet Union lent materiel to the liberation movement. But it did far more than that. It was a major global superpower that stood at the head of the “progressive forces” for national liberation and socialism against the “West” and capitalism, viewed as an iniquitous and exploitative system to ultimately be overthrown.

Many of the ANC’s leading exiles studied in the Soviet Union or its Eastern European satellites and believed themselves to be part of a global movement for progressive change. They no doubt saw themselves as one day presiding over a South Africa with a command economy in which a powerful state would see to it that all toed the party line or suffered the consequences. The pattern for this sort of “democratic centralism” was already in place in the exiled ANC where it was dangerous not to toe “the line”. The likes of Pallo Jordan were among those interred for failing to hold the right views.

There were, of course, many in the ANC leadership who saw through the Soviet propaganda and, having spent time living in the socialist experiments of the Eastern Bloc, realised that there was an absence of freedom in these states where re-education camps and prisons were used to deal with dissenters.

The internal supporters of the ANC — trade unionists such as Cyril Ramaphosa — had already pivoted towards democracy, insisting on transparent leadership elections and scepticism about the possible abuse of state power borne out of their experience of repression at the hands of the militarised apartheid state of PW Botha in the 1980s.

The collapse of the Soviet Union, which began with an uprising of dockworkers in Gdańsk, Poland, in 1980 and ended a decade later with the people of the former Soviet republics eagerly embracing democracy with anti-authoritarian guarantees, nonetheless came as a shock to the diehards in the Struggle. They were suddenly faced with evidence that the states they identified with were despised by the people who lived there and that the democratic state — viewed as an instrument of capitalist control — was more desirable.

This opened the way for the ANC’s pragmatists — the exiled Thabo Mbeki and Ramaphosa, for example — to shift the party on to a more liberal democratic footing.

The eventual outcome of the negotiations was a social-democratic Constitution with liberal democratic characteristics. It at once compelled the state to bring about the transformation of society while checking the state’s power to act in ways that undermined individual freedoms.

When Jacob Zuma, the head of the ANC’s notorious exiled intelligence operation, became president, the criticism of the judiciary rose to a crescendo and, in a very East German turn, efforts were made to shut down the free press in the interests of “state security” with legislation and a “media tribunal” to punish those who dared publish what the state saw as falsehoods.

This Constitution with its limits on state power was never fully embraced by Zuma and his supporters and to this day there are frequent public criticisms from others — most recently by Lindiwe Sisulu — over the independence of the judiciary.

By the time Zuma reconnected the ANC to Russia with an attempt to mortgage the state to finance a “nuclear deal”, both parties had fundamentally changed, but they saw once again that they were in alignment, this time over far less noble goals. The ANC had morphed from a liberation movement to the manager of a kleptocratic elite that was “capturing the state” and Russia had become the model of a kleptocracy ruled by oligarchs all working in the service of Vladimir Putin.

South Africans and Russians began tying up business deals and the number of meetings between Zuma and Putin soon became too many to count

There were efforts made to get gas from Gazprom and there are some who believe that Gazprom might be the intended beneficiary of the government’s new appetite to move to gas to power the electricity grid.

The State Capture project was thwarted and the Zuma faction was placed on the back foot. But they have yet to face the full might of the law as the National Prosecuting Authority dithers over prosecuting them. And the relationship between the Russians and the party elite goes deeper than we think.

Now the ANC, having returned to its Russian lodestar, faces a second rude awakening. This time it is not the Berlin Wall falling, so much as the free world erecting a wall of isolation around Russia — a Berlin Wall in reverse, this time insulating the West against Putin’s excesses.

The pivot of Ukrainians away from Putin’s Russia is a pivot towards democracy and development. As much as this must annoy Putin’s version of Cold War history, it’s there in black and white: the Warsaw Pact did not vote to stay with Russia, just as the Soviet Union broke up for good reason — it delivered much less than the Western model, no matter how imperfect the latter may be. Whatever his dreams, Putin is not going to be able to push Eastern Europe back. The expansion of Nato has effectively prevented that. Otherwise, Putin might be attacking not only Ukraine, but the Baltics, Poland, Romania and others.

The ANC reaction has been bizarre, a confused cry of anguish to a reminder of the repeated failures of their Cold War patrons and the mythologies attached, and the upset to their current plans. But it is notable that by far the most impassioned announcement on Ukraine made to date has been the cry of pain from the ANC’s spokesperson, Pule Mabe, over the cessation of broadcasts of Russian TV, a channel where fake news is company policy.

For the ANC this should pose a conundrum. What Putin appears to be doing with Chechnya, Georgia and now Ukraine is rebuilding part of the Russian empire. For a country that fought against the evils of empire, it seems strange that South Africa seems happy to endorse the remaking of an old empire. If anything, it suggests that the party is still captured.

While the consequences of this ANC line have yet to fully play out, the outside world should now be clear about what the party stands for — and the extent to which it has sold out on its core values.

The ANC, like Putin, finds itself not only on the wrong side of history, but flogging the wrong version of history too — it has decided it will stand with the opportunists and not the democracies. DM

Dr Mills and Hartley are with The Brenthurst Foundation. www.thebrenthurstfoundation.org

ByWallace Gregson

Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine Means Detterence Must Be Strengthened in Europe Now: Retired British General, and former NATO Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe Richard Shirreff, said it best in the 25 February Financial Times:

At a single stroke, Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has announced a new era for Europe. Russia’s unprovoked attack on its democratic neighbor is nothing less than the return of what Otto von Bismarck called: “the politics of iron and blood” to Europe. The world that we knew before February 24, in which the rights of sovereign states to live in peace was guaranteed by a respect for international law without armed force, has gone forever

This is the return of warfare on a scale we have not seen since the second world war, a return to state-on-state warfare, a massive premeditated, merciless (sic) and cruel assault by an aging, isolated, nuclear-armed autocrat determined to re-establish Russian power in the former Soviet empire and to bend their populations to his will.

This is a new era indeed. Putin’s 2014 deployment of “little green men” – masked soldiers in unmarked uniforms – to annex Crimea and reinforce Russian separatists in Eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region elicited little effective response. Conclusions were drawn in Moscow.

Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine, apparently assuming continued Ukraine weakness, a disunited West, an ineffective NATO, and a conflict-averse economy-oriented European Union has foundered. The resistance of Ukraine’s armed forces and more importantly the people of Ukraine proved much tougher than expected. Rather than a short, sharp, two-medal/one-promotion war for Russia’s armed forces, Putin revitalized the West’s liberal order.

If truth is the first casualty of war, our comfortable assumptions, implicit and explicit, must be the second.

Perhaps the most welcome assumption trashed is that war is solely the business of the armed forces. The rest of the nation could “go shopping” as we were told at the onset of the 911-era wars. Just be sure to say, “thank you for your service”. Perhaps we came to this assumption with reason. Desert Shield/Desert Storm gave us a sense of omnipotence as our second “unipolar moment” began after the fall of the USSR (This second moment was destined to be equally short-lived). Triumphalism reigned, with little public sacrifice required. Implicit or explicit, war as the exclusive province of the military, not the nation, was brought forward into the new century.

This assumption had an allied corollary: that NATO and EU nations were so enamored of trade and investment relations with Russia that any unified resistance was impossible because it was not profitable. The same was said about big business and the international corporations. That assumption was also rubbished.

The decision to avoid direct contact of US and NATO forces with Russian forces brought forth many other instruments of national, and international, power to answer Putin’s naked aggression. As a result, we’re getting close to making the old aphorism “all the instruments of national power”, so beloved in the Pentagon but few other places, a reality.

Germany defied expectations with a massive defense increase, a reversal of prohibitions on weapons intended for Ukraine transiting through Germany, and an ending of the Nord Stream 2 Russia to Germany gas pipeline.

Poland is considering transferring some of their Russian fighter aircraft to Ukraine to replace their losses, with the U.S. in turn providing U.S.-built aircraft to Poland. Great Britain, now out of the EU, is nevertheless sending anti-tank weapons and trainers to Ukraine.

Financial sanctions are being employed as a weapon and remain on an ever-tightening trajectory. Maersk, a Danish shipping company meeting the textbook definition of a multinational corporation, announced a suspension of non-essential bookings to and from Russia. Two other shipping giants, MSC of Switzerland and France’s CMA CGM also halted bookings to and from Russia. Europe and the United States, and perhaps others by the time this appears, closed their national airspace to Russian flights. Visa and MasterCard suspended their operations in Russia.

Russia’s reserves of gold and foreign currency are frozen. According to economics experts, roughly half of Russia’s reserves are paralyzed. The Ruble has fallen, and fear of collapse leads to runs on the ATMs and bank windows for withdrawals. Vladimir Putin no longer stands for economic stability.

Informal hacker organizations interrupted their usual activities seeking your money to focus on getting information to the Russian people despite official censorship. It’s logical to assume they are engaged in other cyber warfare. The United States is considering a ban on imports of Russian oil.

Make no mistake, this is a war, however novel the limitations are to date. NATO and EU support to Ukraine’s armed forces strengthens their resistance and adds to Russian casualty lists. Collective economic, financial, and regulatory actions across the globe are exerting a profound effect on Russia, its economy, and its people. Vladimir Putin charged that Western sanctions are akin to a declaration of war. He also made just enough comment about nuclear weapons, ordering nuclear deterrence forces to high alert, to indicate their relevance to this conflict. He has an abundance of tactical nuclear weapons.

There is no reason to believe Russia’s ambitions are limited to Ukraine. Putin has long sought to recreate the Soviet empire in Europe. Russia has Belarus. He covets others. Eastern Europe’s NATO nations understand this well. They well remember life before freedom.

There is no obvious way out. “Off Ramps”, so popular with diplomats and negotiators, are hardly obvious. This conflict will not be a brief episode; it will be a long haul. It is a profound threat not only to Europe but to every country. Other autocrats in other regions are watching closely.

The post-WW II global order that – thus far – prevented a third world war despite many hot campaigns beneath the nuclear threshold, is threatened. Effective nuclear and conventional deterrence, defined as an undoubted capability to prevail, must be established and strengthened. Recent reinforcements in Europe are welcome, but much more is needed. There will be a cost for this, of course. But better a cost in treasure than in the massive loss of life and the return of a dark autocratic era to the world.

If the lamps are to remain lit across Europe, action this day is needed.

Lieutenant General Wallace C. Gregson (RET), Jr. serves as Senior Director, China, and the Pacific at the Center for the National Interest. He retired from the Marine Corps in 2005 with the rank of Lieutenant-General. He last served as the Commander, U.S. Marine Corps Forces Pacific; Commanding General, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific; and Commander, U.S. Marine Corps Bases, Pacific, headquartered at Camp H. M. Smith, Hawaii.Gregson also served in the Obama Administration as Assistant Secretary for Asian and Pacific Security Affairs.

Sophia Ankel

Mon., March 7, 2022,

Screenshot of a video showing Russian shelling hitting fleeing civilians in Irpin, Ukraine, on March 6, 2022.Andriy Dubchak/Donbas Frontliner

Ukrainians who were trying to flee a town near Kyiv on Sunday were hit by a Russian mortar strike.

The shelling killed eight civilians, including a family who was found dead on the street, the NYT reported.

Journalists who were there captured the moment and its aftermath.

Photo and video show a Russian mortar strike that killed a young Ukrainian family trying to escape the violence on Sunday.

The attack took place in Irpin, a town northwest of the capital Kyiv.

The family was among a group of Ukrainians who were trying to flee Irpin after Russian forces advanced there, The New York Times reported.

The fleeing civilians, who were split up in groups, were running through the streets and attempting to cross a destroyed bridge to Kyiv when the shelling started, The Times reported.

Andriy Dubchak, a freelance journalist with the outlet Donbas Frontliner, filmed the moment the mortar struck the street that the civilians were on. (Warning: Readers may find the footage linked in this paragraph graphic.)

The video showed a man in the foreground speaking as a stream of civilians walked on a sidewalk in the background. Moments later, the mortar strikes the middle of the street, causing a fire, and the camera briefly goes dark before a cloud of dust appears.

As the dust settled, journalists can be heard reacting and Ukrainian troops can be seen hurrying to a group of people lying on the ground.

The Times later reported that they were a woman, her teenage son, her daughter, and their family friend. The report said the daughter appeared to be eight years old.

The Times also featured a photo of Ukrainian troops rushing to help the family on its Monday front page.

Lynsey Addario, a photojournalist who was on the scene working with The Times, said: "Soldiers rushed to help, but the woman and children were dead. A man traveling with them still had a pulse but was unconscious and severely wounded. He later died."

"Their luggage, a blue roller suitcase, and some backpacks was scattered about, along with a green carrying case for a small dog that was barking," she added.

A total of eight civilians, which included the family, died in the attack, The Guardian reported.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky condemned the attack in a Sunday night video message, saying: "They were just trying to get out of town. To escape. The whole family. How many such families have died in Ukraine? We will not forgive. We will not forget."

"We will punish everyone who committed atrocities in this war," he said.

Around 2,000 civilians evacuated from Irpin after Russian forces started pushing through the town over the weekend, police said Monday, The Guardian reported.

The towns of Irpin, Hostomel, and Bucha, which surround Kyiv, were all being targeted by Russians, The Times reported.

Monday marks the 12th day of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Russian President Vladimir Putin previously said the would not target any civilians.

However, the United Nations has recorded more than 1,000 Ukrainian civilians who have been killed between the period of 4 a.m. on February 24 to midnight on March 4, Sky News reported.

Insider's live blog of Russia's invasion is covering developments as they happen.

The Boston Globe

Amanda Kaufman -

FOTO © LYNSEY ADDARIO

A photo of a fleeing young family dead on a street outside Kyiv as a result of a Russian mortar strike has become a symbol of the plight of refugees and the toll the war has wreaked on Ukrainian civilians trying to reach safety.

Lynsey Addario, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist, captured the photo for The New York Times on Sunday as a mother, her two children, and a family friend tried to reach an evacuation route into Kyiv, the Times reported.

In order to get to the route, civilians huddled under a destroyed bridge over the Irpin River before small groups decided to make a run for it to get to Kyiv, crossing about 100 yards of exposed street. According to a video of the blast shared by the Times, civilians were walking along the sidewalk of the street when a shell hit the center of the road, sending a cloud of smoke into the air and killing the family that was nearby. The Times reported that the children included a teenage boy and a girl who appeared to be about 8 years old.

The man who was traveling with the young family had a pulse when soldiers ran over to check on him, the Times reported, but he later died. A green case found near the family contained a dog, the Times reported, and barking could be heard in the video. The photo shows the soldiers huddled around the man as the young family is lying on the ground in their winter coats with backpacks on their bodies. A blue suitcase leans tilted on a curb next to where the mother is laying.

Addario, who has covered multiple wars and humanitarian crises, said in an interview with Times Radio, a radio station from the UK’s The Times and The Sunday Times, that on Sunday she was heading toward an evacuation route for civilians, a site she “didn’t really believe” that Russian troops would target.

“For me, this was outrageous,” Addario said. “I literally watched them zero in on civilians, a passageway that was known to be used for civilians so I think the importance of journalists on the ground here is more pronounced than ever for me, because we have [Russian President Vladimir] Putin saying he is not targeting civilians and I was there, and I witnessed it. We need these accounts public, we need people to see what’s happening, we need to show that the propaganda he’s saying is just not true.”

Addario said after she arrived to the route, she was standing behind a cement wall for cover while assessing the situation. Mortar sounds started coming in about 200 meters away from where she was, Addario said, but she assumed Russians were targeting an area nearby where the Ukrainian military was stationed. A security advisor suggested that they leave, but their car was near where the soldiers were positioned, so Addario said she didn’t want to run toward that area. The shells began coming in closer and closer to the civilians, Addario said, and the blast shown in the video landed 20 meters from where she was.

“We were very, very lucky,” Addario said. “We were in a sort of cement box so we hit the ground immediately.”

A video of the blast was captured by a freelance videographer traveling with the Times team. Warning: The video below contains graphic images.

The graphic image illustrated the devastation the war has created, and the photo ricocheted across the Internet and in international newspapers, allowing people who are not experiencing the conflict directly to viscerally understand its toll. Addario’s photo of the family was featured on the top third of the Times’ front page on Monday.

Such photos from journalists capturing the hardship of people fleeing armed conflict or humanitarian crises have become worldwide symbols of those plights, such as the photo of the body of a Syrian boy that was washed ashore in Turkey after his family tried to flee the war in 2015 and “The Napalm Girl,” the photo that captured the horror of children fleeing from a Napalm bombing during the Vietnam War in 1972.

On Instagram, Addario said her photo of the Ukrainian family captures “the brutal toll of war.”

“I’ve witnessed many horrors in the past twenty years of covering war, but the intentional targeting of children and women is pure evil,” she wrote.

The deaths come amid talks between Ukraine and Russia about the implementation of limited ceasefires and the establishment of “humanitarian corridors” to allow civilians in Ukraine to flee. Russian President Vladimir Putin denied in a phone call with French President Emmanuel Macron that Russian forces are targeting civilians, according to French officials, the Times reported. The United States and Ukraine have accused Putin of deliberately targeting them.

On Monday, Russia announced a new push for safe corridors for civilians in Kyiv, Mariupol, Kharkiv, and Sumy, but some evacuation routes led to Russia and Belarus, a Russian-allied country, drawing criticism from Ukraine. Mykhailo Podolyak, an adviser to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, said after the talks that “there were some small positive shifts regarding logistics of humanitarian corridors.”

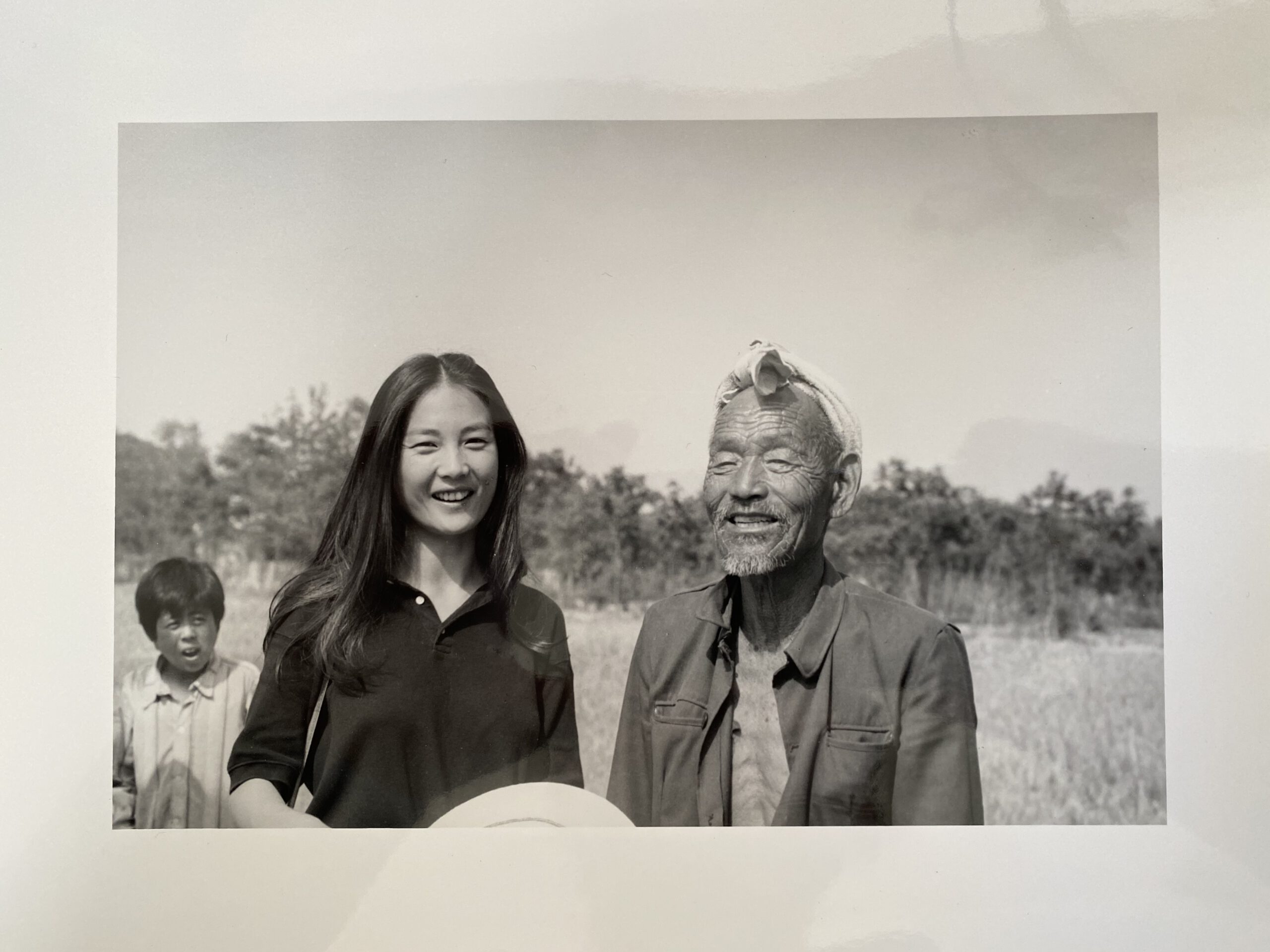

Russian President Vladimir Putin (right) greets then South African president Jacob Zuma during the welcoming ceremony at the BRICS Summit in Ufa, the capital of the Republic of Bashkortostan, Russia, on 9 July 2015.

By Greg Nicolson

Follow

07 Mar 2022 2

As debate rages over South Africa’s position on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Jacob Zuma has backed Vladimir Putin, an ally who shares common conspiracy theories.

As Russian forces continued their shelling of Ukrainian cities on Sunday, former president Jacob Zuma described Russian President Vladimir Putin as “a man of peace” whose actions were justified in response to the threats posed by the US, and Nato’s eastward expansion.

Zuma’s support for Putin was to be expected after South Africa abstained from a United Nations (UN) vote condemning Russia’s aggression, as parts of the ANC are reluctant to support the West’s response to the invasion, with other party allies blaming the conflict squarely on the US and the West.

A statement from the Jacob G Zuma Foundation, written after Zuma “felt it would be remiss of him not to exercise his constitutionally enshrined freedom of expression”, repeated Russian talking points that Putin expressed both before and after the invasion.

Like many other ANC members, Zuma reportedly received training in the then Soviet Union during the struggle against apartheid and he revived South Africa’s relationship with Russia during his 10 years as president, including joining BRICS.

Former finance minister Nhlanhla Nene told the Zondo Commission that Zuma fired him in December 2015 for refusing to approve a nuclear deal with Russia’s Rosatom, which it was estimated would cost R1-trillion.

A confidential document from 2014 that was leaked suggested the government had plans to award the deal to the Russian state energy company before other bidders had a chance to compete.

“The high-water mark for Russia-South Africa relations occurred during Jacob Zuma’s presidency (2009–2018),” said a report released by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 2019.

The report said that in exchange for becoming a member of BRICS, South Africa “appeared to set aside some of its traditional principles – specifically, noninterference in the affairs of sovereign states, the inviolability of borders and opposition to regime change”.

Under Zuma’s leadership, South Africa abstained from voting on a UN General Assembly resolution supporting Ukraine’s territorial integrity after Russia annexed Crimea in 2014.

In its statement on Sunday, Zuma’s foundation said Putin had been “very patient” with the West as he repeatedly explained that Nato’s eastern expansion was a threat to Russia. Ukraine’s Parliament has resolved to work towards joining Nato but there are no signs it will join in the near future.

Zuma’s foundation went further by dismissing Ukraine’s sovereignty: “Surely, in terms of efforts to achieving world peace, the sovereignty of Ukraine and all the democratic dictates cannot mean allowing Nato to establish a presence on its real estate, thus establishing an untenable risk to Russia.”

The foundation continued to argue that the US had invaded states it perceived as threats and that Western countries had hypocritically united against Russia while either leading hostile forces in the past or ignoring previous conflicts.

The foundation said it appeared “justifiable” that Russia was “provoked” and it was “quite fortunate” that Putin had the capacity to respond.

Ignoring the extensive negotiations in the lead-up to Russia’s invasion and Russia’s ongoing failure to adhere to a ceasefire to create humanitarian corridors, Zuma urged Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to negotiate.

“I am certain that His Excellency President Vladimir Putin will reciprocate and bring all in his power to make peace a reality, as I know him to be a man of peace who has worked hard to ensure peace and stability in the globe,” said the former president.

Zuma did not mention Russia’s shelling of residential areas, the already 1.5 million people who have become refugees, or Russia’s alleged use of the internationally banned cluster bombs.

His comments come after South Africa abstained this week from voting on a UN General Assembly resolution condemning Russian aggression and calling on Russia to immediately withdraw its troops from Ukraine. Shortly after the invasion, the Department of International Relations and Cooperation issued a statement calling for Russia’s immediate withdrawal.

The country has stepped back from that position, reportedly after President Cyril Ramaphosa’s intervention, and has recently called for peace through dialogue and mediation, a backtrack clearly aimed at appeasing Moscow and ANC leaders who are cautious of appearing pro-Western.

Some scholars have supported the position, pointing to the UN and the West’s double standards on international conflict.

“I think it is entirely appropriate to do what the government has done. Why is it taking sides if you abstain and it is not taking sides if you vote for the resolution? If you vote for the resolution, you should be supporting the other side,” Professor Steven Friedman told the Mail & Guardian.

“The point in terms of the morality of this issue is that the bombing of Ukraine is totally unacceptable but so is the 70-year occupation of Palestine, and so is the bombing of Iraq, so is, to get back to Palestine, reduction of Gaza to rubble… the Saudis are bombing Yemen.”

The SA Communist Party noted the racism reported by minorities fleeing Ukraine and called Nato the “primary aggressor” in the conflict, blaming Ukraine, Nato and the US for the violence meted out by Russian troops.

For some leftists, the Russian illusion of socialism, which has long given way to kleptocratic and authoritarian nationalism, remains a rallying point against the dominance of the US and western Europe.

For others, that the traditional centres of capitalism and imperialism (ignoring Russia’s current efforts) are against Russia is a rallying point.

Zuma’s support for Putin goes beyond ideology. His foundation’s statement said he was removed from office as state president before he finished his term “by the Western forces using their forces that they are in control of within some structures of our government, and some that they control in the ruling party”.

Zuma resigned as South African president under pressure from the ANC in 2018 after Ramaphosa won the party presidency months earlier. In 2008, former president Thabo Mbeki was pressured to resign before the end of his term by Zuma’s ANC faction in a similar fashion.

The foundation mentioned the Constitutional Court case against the former president, which resulted in his brief incarceration, after Zuma refused to appear at the Zondo Commission or participate in the Constitutional Court hearings.

“In whose interest was this done?” the foundation asked, suggesting it was the same forces trying to bring down Russia with sanctions. DM

Dissing Dissent

Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, Appendix V

迥

The GOP in the United States of America and the CCP in the People’s Republic of China have long demonstrated eerily similar traits: an obsession with distorted historical narratives coupled to delusional nostalgia; the heroic defense of patriotic education; destructive sectarian political behaviour; intolerance of dissent and enmity towards civil society; a proclivity for rule by secretive cabals of power-brokers; a crippled vision of individual rights and collective responsibilities; a worldview based on what in recent years has become known as ‘fake news’; a fixation on conspiracy theories and systemic paranoia; the promotion of hate and resentment; self-affirmation provided by a claque of toadies, ambitious politicians and unprincipled media figures; an admiration for and the cultivation of oligarchs both at home and abroad; an obsession with race and ideological rectitude shored up by glib sophistry; the targeting of minorities for political advantage; the drumbeat of militarism; an apocalyptic view of the world; and, a penchant for rhetorical warfare, among many others. These characteristics shared by both political organisations are at their core informed by a fundamental disdain for democracy, the rule of law, equality, independent critical thought and free speech.

During the presidency of Richard Nixon, the GOP’s Southern Strategy and the Powell Memorandum, commissioned in 1971, contributed significantly to the long-term drift in American politics. As we commemorate Nixon’s China trip in February 1972, we also remember the more baneful aspects of his legacy.

In 2022, the three great powers — the former Soviet Union, the United States and China’s People’s Republic — that clashed during the Cold War decades coexist in an uneasy new configuration. The Soviet Union is now the Russian Federation ruled by the autocrat Vladimir Putin; China is dominated by a willful strong man of its own, Xi Jinping; and, for its part America struggles with the virulent legacy of Donald J. Trump, the GOP’s despotic dotard. The three hegemons — two of which hold the reins of power while the third plots a second coming — hold sway over their respective ‘empires of lies’ and immense destructive potential.

***

I am grateful to Orville Schell, Arthur Ross Director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at Asia Society in New York, for his kind permission to reprint ‘Dissing Dissent’, an essay by his late wife Liu Baifang, in our series ‘1972 朝 — Coups, Nixon & China’.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

26 February 2022

***

1972 朝 — Coups, Nixon & China

- 嘩 — The Coups of 1971

- 見 — A storied Handshake, an excised Interpreter & a muted Anthem

- 撼 — A Week That Changed The World

- 蒞 — Nixon’s Press Corps

- 迓 — ‘Welcome to China, Mr. President!’

- 迥 — Dissing Dissent

- 鞭 — The President & The Chairman in Retrospect

- 書 — A 2012 Letter to the Chinese Embassy

***

Further Reading:

- Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, Appendix I 捌 — A Beijing Winter after the Summer Olympics, 4 February 2022

- Spectres & Souls — Vignettes, moments and meditations on China and America, 1861-2021

- Jason Stanley, How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them, New York: Random House, 2018

- On the Eve — Watching China Watching (XIII), China Heritage, 29 January 2018

***

Liu Baifang Worries About America

Orville Schell

My now departed Beijing-born wife, Liu Baifang, grew up in Mao’s China as his most brutal political campaigns were sweeping the land during the 1950s, 60s and 70s. As a small child she almost died of starvation after Mao’s Great Leap Forward communized Chinese agriculture causing the deaths of some thirty to forty million people.

She arrived in the United States in the late 1970s just as “reform and opening” was being embraced by Deng Xiaoping and ultimately attended the University of California, Berkeley, where she felt only relief to at last be in a country where people were not imprisoned for speaking their minds.

However, in 2003 as she began observing the worrisome early signs of the Bush Administration’s attempts to suffocate political debate and create alternative realities when the real world collided with their own ideological positions, she began feeling a growing uneasiness. The thought that the very kind of political forces that she’d experienced in China during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, that she thought she’d vacated when she left China, were now proliferating in her new country left her uneasy. She often remarked on how dispiriting it was to observe the Republican Party evincing the same kinds of Leninist tendencies of group think, censorship of free speech, the manipulation of facts, and distortions of the historical record as she’d seen living under the Chinese Communist Party.

Despite her strong views, Baifang was one of the most un-self-promotional people I’ve known. She never sought the limelight, much less sought, or even accepted, invitations to publicize her own personal political views. Besides the article below that appeared in the Los Angeles Times in 2003, the only other time she ever expressed herself publicly was following the Beijing Massacre in 1989 when after returning home from Beijing, she consented to go on NBC’s Nightly News with Tom Brokaw to express her outrage over what had just happened in her natal city.

As numerous countries around the world are now once again moving toward authoritarianism, and as even the U.S. — especially under the administration of President Donald Trump – has shown that it, too, is no less vulnerable to autocratic tendencies than any other country, her editorial from almost two decades ago is perhaps worthy of reprise. For it reminds us that no nation – no matter how strong its democratic institutions – is exempt from the forces of nationalism, extremism, and even fascism; that there are always incipient forces in readiness just waiting to spring forth from the dark side of mankind’s experience to opportunistically take the political stage, just as we’ve recently seen these last few days in the Ukraine.

I thank Geremie Barmé for asking me to write these few introductory words in memory of my dear wife just a year to the day after her untimely death. I am proud to have her column reborn here in China Heritage.

Dissing Dissent

Liu Baifang

26 October 2003

Original editorial note: Liu Baifang, who emigrated from China in 1977, lives in Berkeley.

Lately, I find myself worrying about my adopted country, the United States. I’m alarmed that dissent is increasingly less tolerated, and that those in power seem unable to resist trying to intimidate those who speak their minds. I grew up in the People’s Republic of China, so I know how it is to live in a place where voicing opinions that differ from official orthodoxy can be dangerous, and I fear that model.

Like so many others, I arrived in the U.S. enormously relieved to have left my “socialist” homeland. During Mao Tse-tung’s “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution,” intellectuals were persecuted, physically intimidated, imprisoned and, all too frequently, killed. Educated people, known as “the stinking ninth category,” were terrified into political silence after witnessing the dire consequences of voicing any suggestion of dissenting views. My parents were engineers, educated people, and so my family was separated and then “sent down” to labor among peasants in the countryside. We were punished merely for being educated.

During this time, there was a dizzying succession of “correct political lines” and an endlessly changing kaleidoscope of labels used by the Communist Party and the state to isolate anyone who disagreed with official thinking. People who criticized the government were dubbed “counterrevolutionaries,” or “capitalist roaders” or “running dogs of American imperialism.” They were “bourgeois liberals” or “wholesale Westernizers.” People tarred with such labels lost friends, jobs and reputations — even spouses. Families were destroyed. When it came to politics, no room was left for ambiguity, doubt or disagreement. We had to pretend to believe that our leaders always knew best, and to toe the political line. With all criticism stifled, China lost the ability to examine and correct even its most abjectly self-defeating policies.

As students, we had to endlessly study the works of Marx, Lenin, Engels, Stalin and Mao. One of the main tenets of this totalitarian system was what Lenin called “democratic centralism,” which prescribed “full freedom in discussion, complete unity in action.” The Party hierarchy embraced the “unity in action” portion of the message, but true free discussion was out of the question. As Mao said: “The minority is subordinate to the majority, the lower level to the higher level, the part to the whole, and the entire membership to the Central Committee … . We must combat individualism and sectarianism so as to enable our whole party to march in step and fight for one common goal.”

Those courageous or foolish enough to dissent were marked and then ruthlessly hounded into submission. The suffocation of discussion and debate — never mind the suicides and killings — crippled every realm of life, from science and literature to politics, economics and even the most basic human interactions. Noted astrophysicist Fang Lizhi told me that he had been unable to teach the big-bang theory of cosmology during the Cultural Revolution because the notion of an expanding universe was a manifestation of “bourgeois idealism” that did not fit with Engels’ idea that the universe must be infinite in space and time. There were myriad other examples everywhere around us of the ways in which the nation’s ability to find the truth were affected by this savage intolerance.

So why are these 40-year-old stories of political rigidity in a faraway land relevant in America today? I’m certainly not suggesting an equivalence between the political climate in America now and China then. But I am getting a whiff of the Leninism with which I grew up in the air of today’s America, and it makes me feel increasingly uneasy.

I could not help but think about China recently during the flap over former State Department envoy Joseph C. Wilson IV, who angered the White House with his finding that documents suggesting Iraq had tried to acquire nuclear material from Niger were in all likelihood forged. The administration went ahead anyway in citing the documents as part of its justification for invading Iraq. After Wilson wrote an article for the New York Times calling attention to the deception, someone in the administration allegedly leaked information to the press that Wilson’s wife was an undercover CIA agent. In China, it was not just one official like Wilson who was targeted for retribution but countless individuals, many of whom spoke unwelcome truths about their country, only to be rewarded with public shaming or prison sentences.

When I hear our president, in this time of soaring deficits, continue to insist that tax cuts are the key to national prosperity, even though countless economists have warned against them, I cannot help but remember how Mao used to say that China didn’t really need “experts,” only people who were Red. Mao’s inner circle attacked anyone who questioned whether “class struggle” would ultimately solve all China’s problems.

I also worry about what I see happening to our media and freedom of the press. The Bush administration has repeatedly made clear that it does not welcome skeptical, penetrating questions. White House spokesmen have made it clear that they view the Washington press corps as a corrupting “filter” on the news. Reporters and publications seen as unsympathetic to the administration’s goals find it harder to get access to officials. Recently, Bush made an end run around the entire White House press corps by going directly to regional television outlets in the hopes of being better able to spin the news at the local level.

Indeed, Bush press conferences, which I enjoy watching, seem to me to have become more and more like those held by the Chinese Communist Party: Nothing but the official line is given, and probing questions from reporters, which are crucial to advancing the public’s understanding of the government’s actions, are often evaded or ignored. Moreover, as Hearst Newspapers columnist Helen Thomas, dean of the White House correspondents, recently learned, too-persistent questioning on sensitive issues means that the next time you are ignored, even relegated to the back row of the briefing.

Open inquiry, freedom of expression and debate are essential parts of a well-functioning democracy. When leaders disdain debate, ignore expert advice, deride the news media as unpatriotic and try to suppress opposing opinions, they are likely to lead their country into dangerous waters. Even China now seems to have learned how dangerous it is to completely control the press — witness the attempted cover-up of the SARS epidemic — and to be loosening up a bit.

Thus, it makes me all the more discouraged to find the U.S. moving backward. When honest government officials and outspoken citizens are ignored or, worse, marked for intimidation, it begins to seem that the Bush administration is acting more in keeping with Lenin’s notion of democratic centralism than with the founding fathers’ notion of the necessity for a sometimes inquisitive citizenry and a free press.

I am grateful to have become an American and to now belong to a country that has had an inspiring and enduring and true commitment to letting “a hundred flowers bloom,” as Mao, hypocritically, once said. What has made the U.S. such a beacon to people like me is that it has always been principled, confident and strong enough to let its people debate and criticize government policies without suggesting that the critics are somehow less than patriotic.

When our government loses its tolerance for a full range of views on national and world affairs, it is veering toward the authoritarian world that speaks in one voice, the very political model it has so often stood against — even fought against. I hope I will never again have to live in such a world.

***

Source:

- Liu Baifang, ‘Dissing Dissent’, Los Angeles Times, 26 October 2003

***

The Pandemic of Fear & the Angel of Dread

Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, Appendix VII

懼

‘It will need the whole of Europe to keep those gentlemen within bounds.’

— Frederick the Great on the Russians

quoted in Norman Davies

Europe: A History, 1997, p.649

In response to a visit to Babyn Yar (Ru.: Babi Yar) outside Kyiv in 1961, Yevgeny Yevtushenko (1932-2017) published a poem that the composer Dimitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) made the centre piece of his Symphony No. 13. Composed in July 1962, the symphony premièred in Moscow that December. Widely acclaimed during the short-lived Soviet ‘thaw’, Symphony No. 13, also known by its subtitle ‘Babi Yar’, generated considerable controversy, in particular because it affirmed the theme of Yevtushenko’s poem which was anti-Semitism, both past and present. Nonetheless, Shostakovich’s work is credited with having pressured the Communist Party bureaucracy of Ukraine to build a memorial to commemorate the massacre of some 34,000 Jews and many others at Babyn Yar by the Nazis in 1941. Yevtushenko himself said that Shostakovich was the moral architect of that memorial.

On 3 March 2022, Alex Ross, the music critic of The New Yorker wrote:

‘Of late, I’ve been listening to the enigmatically gentle music of Valentin Silvestrov, among other Ukrainian composers. I’ve also turned to Shostakovich, the angel of dread. His Symphony No. 13 is subtitled “Babi Yar,” in honor of one of the most horrific massacres of the Holocaust. On Tuesday, a Russian missile reportedly killed five people in the area of the Babyn Yar memorial, in Kyiv. The symphony’s fourth movement is an immensely chilling setting of Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poem “Fears,” which begins with the ironic announcement that “fears are dying out in Russia” and goes on to say: “I see new fears dawning: / the fear of being untrue to one’s country, / the fear of dishonestly debasing ideas / which are self-evident truths; / the fear of boasting oneself into a stupor . . .” As war fever mounts on all sides, those words and that music might haunt the citizens of all lands.’

— Alex Ross, ‘Valery Gergiev and the Nightmare of Music Under Putin’

The New Yorker, 3 March 2022

***

Readers of China Heritage will be familiar with our argument that the Chinese Communist Party’s civil war within the borders of China Proper, and its conquest of much of the former territory of the Qing Empire (which was claimed by the Republic of China established in 1912, the successor regime to the Qing), in particular Greater Tibet and Xinjiang (but not Mongolia or vast tracts of land ceded to the Soviet Union and Kim Il-sung’s Korea by Mao Zedong) has lasted for over seventy years. Beijing’s imposition of a ‘Law on Safeguarding National Security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region’ on 1 July 2020 formally marked the third front in the Communist’s decades-long war of attrition. Taiwan is the fourth front in China’s ongoing uncivil war.

These lines from Yevtushenko’s poem ‘Fears’ страхи resonate with the theme of our consideration of the Xi Jinping decade:

I wish that men were possessed of the fear

of condemning a man without proper trial,

the fear of debasing ideas by means of untruth,

the fear of exalting oneself by means of untruth,

the fear of remaining indifferent to others,

when someone is in trouble or depressed,

the desperate fear of not being fearless

when painting on a canvas or drafting a sketch.

Here, the poet also unwittingly predicted his ongoing balletic accommodation with the Soviet establishment.

***

This is Appendix VII of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium. When China experiences its next ‘thaw’, the works of those who bore witness to the Xi interregnum honestly may enjoy the recognition that they are presently denied.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Distinguished Fellow, The Asia Society

6 March 2022

***

Related Material:

- Other People’s Thoughts, XXIX, 4 March 2022

- Orville Schell, ‘Putin and Xi’s Imperium of Grievance’, Project Syndicate, 1 March 2022

- Liu Baifang & Orville Schell, 迥 — Dissing Dissent, 26 February 2022

- Geremie R. Barmé, A.M. Rosenthal, et al, ‘Beijing, 1st July 2021 — ‘It was a sunny day and the trees were green…’, China Heritage, 1 July 2021

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘Viral Alarm — When Fury Overcomes Fear’, China Heritage, 24 February 2020

- Yevgeny Yevtushenko, страхи (‘Fears’)

- Shostakovich, ‘Babi Yar’: IV. Fears, Symphony No. 13 in B-Flat Minor, Op. 113, YouTube

***