Governance and Social Conflict in a Time of Pandemic

Striking for life

On Monday March 29th, General Electric factory workers staged a protest against the thousands of layoffs announced by the company’s management, demanding the reconversion of production and asking a simple question: “If GE trusts us to build, maintain, and test engines which go on a variety of aircraft where millions of lives are at stake, why wouldn’t they trust us to build ventilators?”

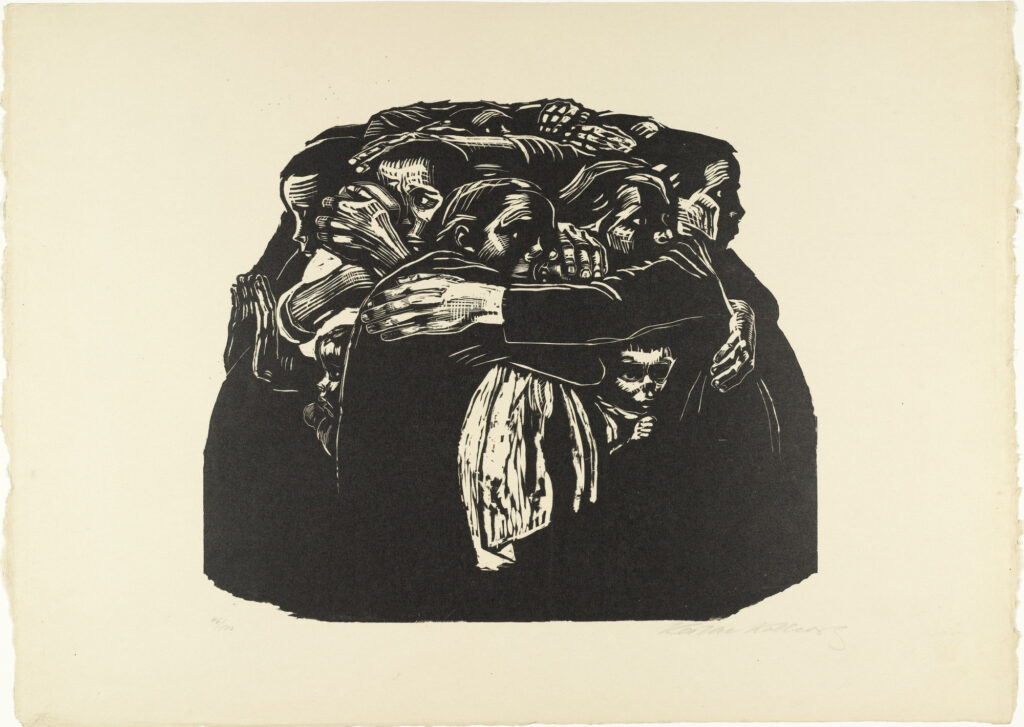

This was one among many strikes of varying shades of legality that workers across multiple sectors have staged around the globe. A wave of strikes in March forced the Italian government to stop non-essential production, though the battle is still far from being entirely won. Amazon and other logistics workers have staged protests and strikes in France, Italy, the United States and other countries to protest against unsanitary conditions and lack of personal protective equipment, while workers in non-essential production have walked off, sicked out, or simply not shown up to work, refusing to risk death in order to increase companies’ profits. As one of the organizers of the Staten Island Amazon protest who was later fired by the company in retaliation, Chris Smalls, put it in an open letter to Jeff Bezos: “because of Covid-19, we’re being told that Amazon workers are ‘the new Red Cross’. But workers don’t want to be heroes. We are regular people. I don’t have a medical degree. I wasn’t trained to be a first responder. We shouldn’t be asked to risk our lives to come into work. But we are. And someone has to be held accountable for that, and that person is you.” Workers in the healthcare, food, sanitation, retail and public transportation sectors increasingly resist being sent to slaughter and are staging various kinds of protests to remind the rest of the world that celebrations of the new working class heroes are not enough: they are no martyrs to be sanctified, they want protections and better working conditions and wages.

Workplaces are not the only theater of struggle in these times of pandemic. Tenants, many of whom have lost income and jobs and live in areas with various kinds of shelter-in-place orders, are organizing to stop rent payments and resist evictions. Inmates are rioting and protesting, from Iran to Italy to the United States, in fear that prisons will quickly turn into death camps due to the virus. Mutual aid efforts and organizations are mushrooming, intensively using social media to coordinate efforts and cater to people in dire need. While some of these struggles and strikes have been staged or coordinated through pre-existing political and social organizations, many are in excess of the previous organizational infrastructure and are rooted instead in spontaneous behaviors of refusal, resistance and solidarity, and in the emergence of self-organization from below as a response to an unprecedented crisis.

In the surreal, suspended atmosphere characterizing our current predicament, it would be easy to focus our attention only on the catastrophe unfolding in front of our eyes, on the relentless cry of sirens breaking the silence of our emptied cities, on the counting of deaths and contagion, and on the looming economic depression. But this strange, anxious time we are experiencing is also filled with struggles, acts of solidarity, and processes of class composition and self-organization.

What all these struggles have in common is the simple refusal to let oneself or others die for capitalism, a refusal that lays bare what the Marxist Feminist Collective in a statement about the pandemic has labeled the contradiction between profit-making and life-making or social reproduction at the very core of capitalism.

By refusing to put profits over lives, these struggles are opening at least two main frontlines of confrontation. The first involves the immediate management of the pandemic and its class, racial and gender dimension; the second with longer-term social transformations. At a moment when a number of countries are putting in place some version or another of neo-Keynesian measures to avoid economic collapse and social unrest, the burning question we are facing is whether these measures will mark the definitive end of the neoliberal era and austerity or not: an outcome that will largely depend on political and social struggle.

On the governance of the pandemic

The pandemic is creating a global conjuncture in response to which various forms of struggle are emerging and proliferating. At the same time, its management is far from being homogenous across national contexts: national political dynamics have their own specificities and generate significantly different contexts for processes of struggle and subjectivation, though against the background of a global conjuncture connecting us all.

From this viewpoint, one of the main limits of the “state of exception” discourse, which focuses on the dangers of authoritarian political turns connected with the suspension of freedoms entailed by lockdowns, is that it simplifies the enormous complexity of the current situation into a night in which all the cows are grey. It also misidentifies the real terrain of struggle in many countries today.

First of all, it is not the case that governments rushed to adopt harsh emergency measures and to suspend liberties. The opposite is rather true: in many cases governments have hesitated and even initially refused to suspend what passes as capitalist normality. This delay is having dire consequences in Italy, Spain, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Sweden, among other examples. When executives did finally decide to institute lockdowns, they did so because they were pressured by healthcare experts, because of fears of the risk of a collapse of the healthcare systems (largely due to the depletion of the healthcare sector caused by decades of austerity cuts and privatizations) and because of protests from below, especially from workers refusing to go to work. In fact, the notion that capitalist states would have an overriding interest in keeping people at home is rather bizarre and factually contradicted by the numerous attempts to envisage a quick return to some form of “normality” that would allow people to go back to work (and to consume).

Within this context, the pandemic has indeed been the occasion for some authoritarian-leaning governments to further concentrate powers within the executive, as is happening in countries like Israel, Hungary, or India. But even this is not a linear and automatic process that applies to all countries governed by an authoritarian far right. In Brazil, Bolsonaro is sticking to denialist positions, even as he is increasingly politically isolated as a result and spurring regional appropriation of emergency powers. In the United States, Trump refused to declare a federal shelter in place order and is insisting in granting gubernatorial autonomy and flexibility in deciding what measures to adopt. China is a case apart, as the management of the pandemic relied on the mobilization of an already existing authoritarian power apparatus.

Rather than imposing abstract formulas upon a complex reality, it is more useful to pay attention to the experimentation with diverse forms of governance, both novel and ageold, in the management of the pandemic. For example, the current undeniable concentration of powers within the executive in Italy or Germany is causing tensions with the executives of regions and Länder, and both of them are in a tense relation with European transnational institutions. In the United States, not only is there no significant transformation in the distribution of powers among federal institutions, but state administrations’ policies differ among each other and are at times in tension with the Federal administration’s incoherent approach. One notable example are the several clashes between Trump and the governor of New York State, Andrew Cuomo, who has risen to the status of Trump’s counterpart, in spite of not being the Democratic candidate to the Presidency. Several European states and the United States are adopting forms of governance that include specific stakeholders in decision making processes: sectors of the national scientific community, big corporations, financial institutions and national business councils. The pandemic has also presented the opportunity for the United States and China to pursue and redefine their geopolitical strategies. It has become an occasion for the Trump Administration to push for regime change in Venezuela and ratcheting up the already abominable sanctions in Iran. China, meanwhile, is adopting a soft power strategy that aims at expanding its international hegemony, sending much needed medical supplies and experts to dozens of countries, an initiative the United States are now eager to imitate: Trump has boasted that he would send Italy $100 million worth of medical supplies even while the United States struggles to find basic face masks for its frontline healthcare workers.

But even these experiments in governance are not going smoothly, challenged by the continuous antinomy between normality and exception: the normality of the working of a mode of social production and the exception imposed by the pandemic upon the social reproduction of life or the normality of the circulation across public spaces – which cannot be entirely eliminated – and the exception of the immobility within private spaces. These experiments in governance are continuously changing, having to face the limits of the current welfare systems, healthcare first of all, and having to navigate the articulation between local, national, and transnational powers. An example is the way in which the autonomy of U.S. state governors is amounting to them bidding against one another for ventilators. Competitions for resources are also taking place in Italy among regional governors. It is impossible to predict now how these experiments will evolve, for the variables at play are numerous, from the conflict between different state institutions to the level of intensity and reach of social conflict from below.

The staggering rise in unemployment, the disruption and delinking of global value chains, and the necessity of reorganizing social reproduction have forced the U.S. and E.U. institutions to take massive economic measures in order to avoid not only economic collapse, but also the explosion of social unrest in response to the looming depression. The features these measures have in common could be defined as a sort of provisional and very partial Keynesianism or “Keynesianism with an expiration date.” As Bue Rübner Hansen wrote: “These policies are ad-hoc and designed to be short term measures, like the doctor of Hippocratian medicine whose decision (krino) acted on the turning point (krisis) in the patient’s health. However, in all likelihood, Covid-19 isn’t a temporary exogenous shock.”

For example, in his daily briefing on Friday April 3rd, Trump declared that the Administration is planning to use money from the stimulus package to pay for the costs of the hospitalization of COVID-19 patients without insurance coverage, rather than extending coverage or reopening enrollment in Obamacare markets. Meanwhile the large majority of the Democratic establishment, including the leading primary candidate, Joe Biden, continued to dismiss Medicare for All even in the face of the epidemic. The $2 trillion of the U.S. stimulus package and the 750 billion Euro allocated by the European Union with the subsequent addition of $100 billion to supplement workers’ incomes are measures that, in spite of their astonishing magnitude, do not challenge the neoliberal framework. In addition to this, no significant provisions are being made for victims of domestic abuse for whom sheltering in place is not synonymous with safety; nor is the increased burden of domestic labor for women being addressed in any way. Moreover, these interventions are often predicated on anti-immigrant and closed border policies, and nothing is being done to free detainees in migrants detention centers and refugee camps where access to healthcare is close to zero and the virus could take thousands of lives.

The clear aim of these measures is the reconstitution of the conditions for the reproduction of capitalist social relations, and certainly not their radical transformation. An intervention in the Financial Times by the former President of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, may be taken as an illustration of the logic behind this massive cash give away in the United States and the European Union. According to Draghi, the current crisis is not cyclical but rather due to exogenous factors. Hence, his proposed recipe is to increase national debt in order to allow big private companies to weather the emergency and then get back to business as usual. And in fact, most of the funds will go to private companies, but without any serious policy in place to save jobs and avoid layoffs, for the mistaken assumption is both that companies will avoid layoffs if they get the cash and will recreate lost jobs once the emergency is over. This is also the logic of the temporary suspension of the Eurozone Stability Pact, which the German government, among others, does not want to become a precedent for a structural transformation of the economic policies of the Eurozone toward the abandonment of neoliberal austerity. Whether the aim of reconstituting the conditions of capital’s reproduction will be achieved or not will depend on a number of factors, including political dynamics and social power relations.

Subjectivation and self-organization in a time out of joint

The present conjuncture is filled with tensions and contradictions. Time is out joint, both dense with events and suspended. Contradictions and ambivalences also characterize forms of sociality, combining social isolation with a surplus of connectivity and communication through an array of social media. We cannot predict now how social life will be transformed as a consequence of the pandemic, but it is entirely possible that forms of what Foucault would label “technologies of the self,” of subjectivation, and of communication will become even more hybrid than in recent times, in the direction of a greater convergence of “real” and “virtual” encounters and languages.

These forms of sociality within the context of the macro-dynamics at play and described above could also have effects on a potential new class composition. To name just a few salient factors: rising mass unemployment; fear of contagion in the workplace and spontaneous behaviors of refusal; the increasing visibility and social recognition of low-wage, racialized and gendered service workers; social isolation; and the blurring of the lines between production and reproduction for those who work from home and have to jostle between increased domestic burden, cramped living spaces, and the times and constraints of waged work.

In this context, diverse processes of struggle and political radicalization are starting to take place. But there are no easy recipes on offer for how to exploit these potentialities opened by the new conjuncture. Lockdown measures themselves pose new challenges to organizational processes and demand the ability to reinvent ways of organizing, protesting, and being effective: how can we make social protest visible at a moment in which traditional ways of doing so – mass marches, rallies, etc. – are out of the question? How can we connect the new wave of legal and wildcat strikes to other forms of resistance and conflict, such as rent strikes and the organization of mutual aid and alternative forms of social reproduction? How can these social struggles become increasingly politicized, rising to the level of the current challenge, which means confronting the power of the state and of transnational institutions?

Inquiry into the new potential processes of subjectivation and struggle would be a first step for trying to give an answer to these burning questions and avoiding the mechanical re-proposition of old organizational models and political strategies which do not take into account historical discontinuities and variables. Inquiry here should be understood not merely as a sociological investigation, but as a process of self-knowledge, self-organization, politicization, and common creation of a new shared understanding of who we are, and why and how we are fighting back.

This is an urgent task for being able to address both frontlines of struggles mentioned above, namely immediate management of the pandemic and long-term transformation of social relations of production. As argued by Rob Wallace and others, modelings of the virus and predictions concerning the duration of suppression measures, such as the report by the Imperial College – which has become the point of reference for the United States and the United Kingdom – are predicated upon the implicit assumption that the neoliberal frame cannot be challenged. As they write: “Models such as the Imperial study explicitly limit the scope of analysis to narrowly tailored questions framed within the dominant social order. By design, they fail to capture the broader market forces driving outbreaks and the political decisions underlying interventions. Consciously or not, the resulting projections set securing health for all in second place, including the many thousands of the most vulnerable who would be killed should a country toggle between disease control and the economy.” Yet, it is precisely this frame that needs to be overcome, with two goals: limiting as much as possible the number of lives that will be taken by the virus, and opposing the strategy of “Keynesianism with an expiration date,” fighting instead to end neoliberal austerity and to transform altogether the capitalist relation between production and social reproduction, which subordinates people’s lives to the accumulation of profits.

One of the memes circulating on Italian social media during the long weeks of lockdown was: “We’re going to be fine.” While this is an understandable wish, it is precisely nothing more than that. Moreover, it implicitly takes the status quo before the pandemic as the normality to which we should aspire to return. Let us be honest: there is no certainty that it’s going to be fine, and the way we were living before the pandemic was neither fine nor “normal” at all, for the current crisis is a consequence of capitalism as a form of social organization and life.

We may yet end up being fine. But that will depend on us, on our ability to prevent a return to business as usual. If the task sounds daunting, and it is, we might remind ourselves that we are not entirely powerless. As Chris Smalls said with absolute clarity: “And to Mr Bezos, my message is simple. I don’t give a damn about your power. You think you’re powerful? We’re the ones that have the power. Without us working, what are you going to do? You’ll have no money. We have the power. We make money for you. Never forget that.”