Free online reading

contents

Introductory remarks

1. The dawn of Alchemy

1.1. The word Alchemy

1.2. Legendary origins of alchemy

1.3. The oldest written sources

1.1. The word Alchemy

1.2. Legendary origins of alchemy

1.3. The oldest written sources

2. Alchemy in the West

2.1. Egypt

1.2. The Hellenistic era

2.3. The Arabic era

2.4. The Christian Middle Ages

2.1. Egypt

1.2. The Hellenistic era

2.3. The Arabic era

2.4. The Christian Middle Ages

3. Alchemy in the Far East

3.1. China

3.2. India and Tibet

3.1. China

3.2. India and Tibet

Concluding remarks

Selected bibliography

Introductory remarks

This paper seeks to investigate the origins and the history of Alchemy. Almost no art or science has been subject to such controversial discussion over centuries than alchemy. It must be said that the alchemists themselves very much contributed to this controversy by keeping their recipes and practices secret. Because of the highly encrypted language and the excessive use of symbols and pictures in many alchemical treatises and works it really does not make wonder that alchemy became denounced as pseudo-science, deception and quite in a few cases even as folly. However, on the other hand there were a number of famous and learned men who seriously believed in alchemy and its possibilities. Also it should not be forgotten that alchemy was the mother of modern chemistry and many alchemists, though by mere chance, discovered on their quest for gold chemical processes and substances that are still in use. Mentioning gold is not to say that this was the one and only aim of all alchemists. As we shall see, alchemists throughout the world actually strove for three aims: wealth, i.e. making and multiplying of gold, silver, and precious stones; longevity, i.e. the panacea universalis, a substance that cures all illnesses; immortality, i.e. the elixir of life which restores youth at any given age.1

In this paper I will try to present the appearances of alchemy in a chronological order, however sometimes it will be necessary to abandon this way because of the parallel development of alchemy in very different regions. Also of interest will be some of the main theories and their development and finally important representatives of alchemy.

1. The dawn of Alchemy

1.1. The word Alchemy

Scholars are not yet sure where the word alchemy actually originates from. The Arabic prefix al- was put in front of an, apparently, much older word. Burckhardt2 traces chemy back to Old Egyptian k ê me/ch ê me = 'black soil' ,which is a name for Egypt, or just 'black' . An argument for that theory is that alchemy later sometimes was named Egyptian Art. According to other theories the word was coined by the Greek alchemists in Alexandria. In Greek it is P0:,^", meaning the stirring of the melted metal. It was then applied to the whole art. Yet another possible origin of the word is in the field of legends to which I will come in the following.

1.2. Legendary origins of alchemy

Basically there are three legends going around about the origin of alchemy. According to the first and perhaps most wide-spread one alchemy was brought into this world by the deity Hermes Trismegistos, who in the course of an ongoing syncretism in Hellenistic Egypt and Greece was equalled to the gods Chnum, Thoth and Ptah. On the basis of that legend alchemy is called the Hermetic Art and if something is sealed air- and watertight it is hermetically sealed.

According to an other legend alchemy, together with magic and other occult arts, came to mankind after the battle of the angels when the Lord threw the rebellious angels out of the heaven. They came down to earth, got married with ordinary women and taught them everything they knew. This knowledge was written down in a book called Chem~. 3 This legend is also apt to explain a possible origin of witches because this book is nothing less than the first Grimoire.4

Finally the third legend says that alchemy was taught to Moses and Aaron by the Lord himself because they were chosen. according to an apocryphal biblical story Moses destroyed the Golden Calf, burnt it to ashes, dissolved the ashes in water and gave the people of Israel to drink. Now, for someone who hears this story it must be quite obvious that if Moses was able to destroy gold so completely he must as well be able to make it.

1.3. The oldest written sources

Unfortunately there are only a few examples of early alchemical writings that have survived till today. Among these artefacts are some fragmentary cuneiform script tablets from old Egypt that contain recipes for making alloys and colouring metals. Burckhardt says that in Egypt alchemy was considered a holy art and therefore was handed down orally. The big fire in the library of Alexandria, too, surely destroyed a number of precious works on alchemy .

The so far oldest known and most famous sources are two papyri from the 3rd century AD. They became known as Papyrus Leidensis and Papyrus Holmiensis5. Both contain a number of recipes for the imitation of gold and silver by forming either gold-containing alloys or simply golden-looking ones like brass. Furthermore they contain recipes for 'making' precious stones and pearls. Some recipes are open deception6. It is held by some scholars that both papyri are compilations of much earlier works. For a very detailed description of the two papyri see the outstanding work of Lippmann. Another source is the tabula smaragdina, ascribed to Hermes Trismegistos. Its authenticity has been doubted at7 not only because the oldest preserved version is an Arabic translation. It contains a very dense summa of alchemy and because of this density is very difficult to understand. There is a number of other works dating back to that period and published under famous names, but most of these works are pseudepigraphs and therefore cannot be taken as a kind of 'authentic' sources.

2. Alchemy in the West

2.1. Egypt

It is very difficult to investigate early alchemy in Egypt, meaning pre-Hellenistic Egypt. Lippmann, Burckhardt et alii hold that here is the true cradle of alchemy, though in a wider sense. The oldest evidences can be traced back to the Old Kingdom (c. 3200 BC). As early as that the Egyptians were good metallurgists. However this metallurgy was in the hands of the priestly caste who claimed to have their knowledge right from the gods Ptah and/or Thoth8. The workshops were in the temples of these gods and the artisans were either priests themselves or slaves of the temple. Bearing this in mind indubitably must have been highly respected for their secret wisdom, a fact that reinforced their power.

Around 1000 BC one can find the first hints of a theory, that there are four elements, Fire, Water, Earth, Air, and everything consists of a mixture of them. If the mixture is changed it theoretically should be possible to transform one substance into an other. This theory usually is ascribed to Aristotle, but apparently similar theories, naming four and sometimes five elements, developed independently in different regions and cultures at about the same time. Also rather early emerged the concept of the seven planets and their corresponding metals, perhaps coming from Babylon.

In the course of time there developed a proper temple industry. They 'multiplied' gold by creating alloys, e.g. electron, with less valuable metals, were skilful in gilding objects for ritual purposes and even created alloys that merely looked like gold, e.g. brass. Apart from these metallurgical enterprises there also appeared the imitating of precious stones and the colouring of glass. The substances in use were mineral salts and certain ashes and slags. At quite an early stage the art of the priests became J,6<@B"D"*@J@H, i.e. was handed down from father to son in order to keep it secret. Burckhardt in particular explains the lack of written artefacts with this secretness.

However, step by step the Egyptian empire declined and foreign influences became stronger. Among those influences were all sorts of philosophical concepts and streams like platonic, pre-Socratic, and Aristotelian philosophy. A new age of alchemy was dawning.

1.2. The Hellenistic era

Several scholars and most encyclopaediae place the beginning of alchemy in this period. Indeed alchemy during this era reached a bright bloom. The centre of this new period became Alexandria with its great library. Characteristic of it was a heretofore unknown religious syncretism. As mentioned above, the Greek god Hermes Trismegistos in Hellenistic Egypt became mixed with the gods Chnum, Thoth, and Ptah and was equally worshipped. The Ouruboros, a snake that eats its own tail, is the symbol of two old Egyptian gods9 and at the same time of the Greek Agathodaimon, also a snake-shaped god. The latter later on was sometimes referred to as Egyptian philosopher, king, or god.10 The Egyptians readily accepted virtually every new philosophical idea and absorbed it into their own thinking, re-shaping and adapting it freely according to their needs. Among the important theories of the time is that of the ovum philosophicum, the egg that contains all four elements. Heraklitos and Xenophanes framed it in the formula ª< 6"Â B?< (one and all). Plato and Aristotle developed a transmutation theory on the basis of the four-element theory. A substance can be transformed into an other substance by adding or reducing certain features. For instance if you add heat to water it becomes steam, i.e. changes its state from liquid to gas. Likewise it must be possible to transmute base metals into silver or gold. The new concept here was that of the prima materia, the black original state of all matter without features. The process is described as follows: first reduce the base metal to the materia prima (black ash, coal, slag, blackness of crows), as the next step the salting ( taricheia, sepsis of Isis), Alloiosis and Metabolè under the influence of the sulphurs, salts, and 'waters' .11 In the phial there is a constant movement "<@(upward, male, active, fire, air, spirit of Mercury) and 6"J@ ( downward, female, passive, Water, Earth, spirit of Sulphur). The reaction of these two sprits creates the homunculus which is rising through the colours to gold. There were lots of imaginations about the time span required for the transmutation. Numbers vary between 9 hours, 7, 14, 21, 40, 41, 110 days and 4, 6, 9,12 months. Likewise there are to be found descriptions of 4 steps of transmutation (nigredo - black, reduction of the metal to the prima materia, albedo - white, adding of purified mercury, citrinitas - yellow, adding of purified sulphur, rubedo - red, the mixture of the ingredients results in gold); 7 steps in connection with the seven planets(calcinatio - Mercury, putrefactio - Saturn, sublimatio - Jupiter, solutio - Moon, distillatio - Venus, coagulatio - Mars, extractio - Sun); 10 steps12, and 12 steps in correspondence to the zodiacal signs ( Aries - calcinatio, Taurus - congelatio, Gemini - fixatio, Cancer - solutio, Leo - digestio, Virgo - distillatio, Libra - sublimatio, Scorpio - separatio, Sagittarius - ceratio, Capricornus - fermentatio, Aquarius - multiplicatio, Pisces - proiectio). There co-existed the concepts of the tetrasomy ( copper, lead, tin, and iron as dead bodies), which is resurrected by the pneuma theion (divine spirit), and the three principles of Mercury (soul), Sulphur (spirit) and Sal (body), the trinity of which was called Androgyn. The most influential concept, however, was the idea of a substance which accelerates or causes transmutation at all, respectively, a substance known as xerion, elixir, philosophers' stone. Natural philosophy of that time held that all metals will one day reach the perfection of gold and that the seed of gold is in every metal. By means of the stone they sought to speed up nature and produce gold or silver in a much shorter time. Another belief was that base metals are 'ill' and have to be 'cured' with 'the stone'. From the 4th century onwards there developed a theory that mercury instead of gold is original part of all metals.

With the decline of the old religion there of course was connected a decline of the status of the priests. In reaction to this the priests adopted the claim of not creating substitutes of equal value but of making gold and silver itself. Under the influence of the younger Stoa superstition and mysticism rose. Alchemy became increasingly connected with magic and mancy. Alchemical treatises began to demand outer and inner purity. The adept should be free from envy, hatred and avarice. What's more, the adept must be chaste and for the time of the work keep a strict diet. Magical formulas and invocations together with purifying rituals emerged. An oath of secretness was established that ruled to speak about the art either not at all, or tecte (encrypted). The alchemist now had to observe the stars and wait for favourable constellations and some authors claimed, that the work must be begun on special days or in a special season. The methods and substances were being more and more obscured and the practical value of the writings gradually sank. As possible causes for the failure of the work were listed envy of demons, bad influence of the planets, the wrong season, ignorance or inappropriate use of the rituals and formulas.

Let me now come to some of the representatives of that period's alchemy and, in passing, their works. The first one to mention is Bolos of Mendes (around 200 BC). He brought with him the idea of the unity of the cosmos and interpreted the works of the Egyptian in this way. He seems to have been a practically working man because he wrote a book called 'Physica et Mystica' (title of the Latin translation). It contains a number of, rather obscure; recipes for the making of gold and colouring of metals. The next one is the disputed Hermes Trismegistos. between the 1st century BC and the 3rd century AD there was been published a vast number of works under the name of Hermes. The actual Corpus Hermeticum consists of 18 works, none of which really speaks about alchemy.

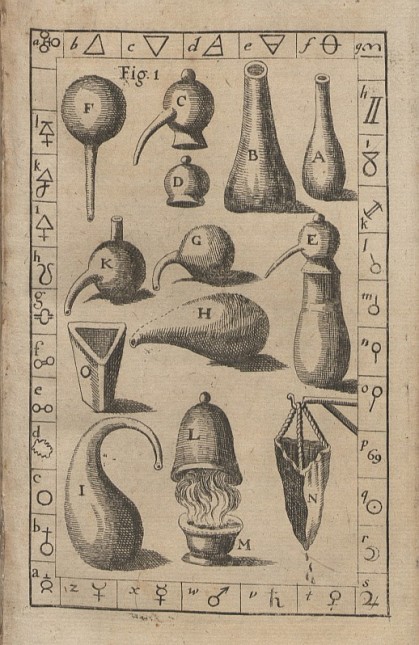

According to Haage the Corpus Hermeticum realiter is more a Gnostic than alchemical work and it merely was interpreted alchemically. The most tangible and historically authentic alchemist of the Hellenistic period, and perhaps its last great one, was Zosimos of Panopolis. He lived at the turn of the 4th to the 5th century. He was both a critical and productive author who built several apparatus himself. Zosimos was convinced of the possibility of transmuting base metals into gold by means of a certain substance. He described it as a dry, intensively red powder and called it P¬D4@< (xerion). His works are 'the divine water', 'of chemical devices and furnaces' ( to him goes back the Athanor13 ), 'of chemistry' and 'of the holy art'. In all his works he stresses that the way to the xerion leads via observation of and insight into nature. He also repeatedly pleads for keeping the art secret and encoded. Those who are really learned and chosen will be able to understand, those who aren't should leave the matter untouched.

Throughout the whole period there emerged lots of pseudepigraphs ascribed to Democritos, Isis, Maria Hebraica, Cleopatra and Hermes Trismegistos. A quite famous example for these pseudepigraphs is the chryspoiia by an author who called herself Cleopatra. It uses lots of pictures and symbols, among these the Ouruboros as symbol of the great work with the words ª< Jò B?< (one is all) inside. The writings of Synesius of Kyrene, Heliodoros, Dioskoros et alii have come down to us, however their historical existence is disputed. The preferred genres of these alchemical works were recipe, allegory, riddle poetry, visions of revelation, didactic poetry and letters, dialogue treatises, and commentaries.14

Evidently the 'making' of gold was very popular and successful in Hellas, because in 296 emperor Diocletian of Byzantium saw himself forced to order the burning of alchemical works, either because he feared that Alexandria could stand up against his kingdom, or he as a Christian deemed these writings heretical. In fact he might have been afraid of an economic chaos because of counterfeit money.

2.3. The Arabic era

While in Hellenistic Egypt and Greece alchemy was still in full bloom a new era was approaching with the expansion of the Arabic influence from Syria and Persia. The Arabs conquered huge areas from Asia via Northern Africa to Spain. Unlike other conquerors they did not destroy the culture and philosophy they encountered on their campaigns but treated them with great interest and respect. According to Lippmann no other expanding culture ever was so tolerant towards other cultures. Unavoidably they came across the blooming alchemy at the school of Alexandria and soon after (c. 7th century) the first translations of Greek works emerged, first in Syrian, later in Arabic. At their work the translators did not hesitate simply to take over Greek terms for devices and substances and prefix them with the Arabic al-15. The Arabs had a slightly more technical view on alchemy. Of course they also worked on transmuting base metals into gold but increasingly they discovered its use for medicine, If 'the stone' (al-iksir, elixir) is able to cure metals it must also be able to cure humans. The Arabic physicians dealt with the humoral pathology of Galenos, a concept on the basis of the four bodily liquids blood, black and yellow gall, and mucus. Galenos thought that if all these liquids are in equilibrium, man is healthy and even-tempered. He explains the human tempers16 with the gaining of the ascendancy of one of the four liquids. The medicine so far depended on herbal remedies. The experiments of the alchemists, however, gradually led to a pharmacopoeia of mineral remedies which step by step replaced the herbs. The same experiments with 'strong, i.e. corrosive, waters' several hundred years later led to the discovery of the mineral acids. The alleged founder of Arabic alchemy is Prince Khalid Jazid Ibn Mu'awija (635-704) of the Umaiyade dynasty. He strove in vain for the crown of the caliph and therefore he allegedly occupied himself with medical, astrological, and alchemical studies. He initiated the translation of several Greek works into Arabic. He gathered a number of scholars of his time at his court but had them incarcerated and executed because the promised transmutation always failed.

A shining authority of Arabic alchemy was Djabir Ibn Hajjan (c.720-819), in the newer research called Geber arabicus, in order to contrast him from Geber latinus who lived at the end of the 13th century. He advocated the experiment and practical work as the sources of theory. According to him mere brooding is futile. He developed a new theory of transmutation. At the beginning the matter must be reduced to the four elements. As a second step the ingredients must be brought into an equilibrium. For that purpose Djabir worked out a system of mathematical proportions that basically goes back to neo-Platonian and Pythagorean ideas. Now the matter must be reconstructed to the configuration of gold. He also worked on the concept of the lapis philosophorum. He defined it as trinity of soul, spirit and body in an equilibrium. In that state it is both volatile and constant, male and female, hot and cold, and moist and dry.

The very voluminous Corpus Gabirianum (8th-10th century) in two versions, one in 112 volumes, one in 70 volumes, is ascribed to him and a man called Al-Hasan ibn an-Nakid al-Mausili who lived in the middle/end of the 9th and the beginning of the 10th century. The long version of the Corpus Gabirianum is an extensive treatise on antique sciences in general. The 30 volumes that have come down to us contain a number of methods to create the elixir out of mineral and/or organic ingredients. The short version, apparently written by Djabir himself, consists of 70 volumes and contains an again extensive but complete and systematic description of the Djabirian alchemy. In these books Djabir repeatedly refers to the works of Greek authorities, not knowing that most of these are pseudepigraphs. Later ( in the 12th century) Gerhard of Cremona translated them into Latin and published the under the title Liber divinitatis de LXX.

Another very influential alchemist was Abu Bakr Muhammed ibn Zakarija 'ar-Razi (c.865-925) , often called Rhazes. He was a famous and successful physician and managed a hospital in Baghdad. He occupied himself with the Greek philosophy of nature and the Galenic humoral pathology and alchemy. In general he accepted Djabir's theories except his idea of the proportions of the ingredients. He again adopted a Sal-Sulphur-Mercury theory. During his practical studies he worked out a new classifying system. He distinguished between animal, vegetable, and earth-like matter and sub-divided the latter into volatile (spirits), metals (bodies), stones, vitriols, boraxes, and salts, thus making a big step towards systematic chemistry. Another theory of his was a corpuscular theory according to which all matter consists of atoms. The properties of the single matters depends from the density of the atoms - a very progressive view regarding the time when it was formulated. He perhaps did not know how close he was to truth. His main work was the Liber Secretorum 17 in which he laid down his theories and methods. Towards the end of his life he re-edited it and published an abridged version under the title Secretum Secretorum.

The latest one who deserves mentioning in the context of Arabic alchemy is Abu Ali al-Hussain Ibn Abdallah Ibn Sina (980-1037), latinized Avicenna. Like his colleague Rhazes he actually was a physician of high reputation. He studies the works of his predecessors and comes to believe that a real transmutation of metals is plainly impossible. Alchemy and the alchemists only can copy and imitate nature. He occupies himself with the elixir only for medical purposes. The search for gold has been abandoned for the sake of longevity. His main work Canon Medicinae (in the 12th century translated by Gerhard of Cremona) is one of the fundamental works of mediaeval medicine. A large number of pseudepigraphs was published under his name.

2.4. The Christian Middle Ages

During the 11th and 12th century Christian scholars became increasingly interested in science and philosophy of the Greek and Arab and thus became aware of alchemy as well. Cities like Paris, Salerno and Toledo became centres of education and science. Many philosophical and alchemical were translated into Latin, first of all in Spain and Sicily, then still occupied by the Arab. These works were regarded as the wisdom of 'the Old' and avidly studied, however some scholars, among them Adelard of Bath (1070-1146), stood up against the blind and un-reflected reception of the works. After their opinion one certainly should read these works but should not see in them the ultima ratio but rather a basis for own research. His contemporary Hortulanus wrote a compendium and a dictionary of alchemy and published a commentary of the tabula smaragdina. Alanus ab Insulis (1125- 1203) again wrote against the lack of scholarly self-consciousness he encountered among his contemporaries. He was abbot of Clairvaux and a very learned man. Because of his almost biblical age his contemporaries believed that he must have found the elixir. he wrote a book of recipes in rather obscure language. The books that by that time were read most were Djabir's Liber divinitatis de LXX, pseudo-Rhazes Liber lumen luminum and De aluminibus et salibus, a mixture of exoteric- scientific parts and esoteric - mystical allegories.

One of the greatest scholars of the middle Ages, Albertus Magnus (1193-1280), dedicated much of his life and work to alchemy. He, despite the works of Avicenna which he should have read, believed in the possibility of the transmutation and accordingly took effort in research. The essence of his theories and ideas he wrote down in his important works De Alchymia, De rebus metallicis et mineralibus, and Octo capita de philosophorum lapide. His contemporary Roger Bacon (1214-1292), like Albertus Magnus a very learned man18, had studied and taught at the important universities of his time. Bacon enjoyed a high reputation for trying out all experiments he read about. His concern for alchemy, however, caused him, he was member of the Franciscan order, several problems because about that time beginning in Spain alchemy became banned as un-Christian and pagan. In his main works Speculum Alchimiae, Opus tertium and his other writings he turned against the rising influence of occultism and magic19. He pleaded for alchemy as a serious science and a basis of philosophy of nature, and its practical side has nothing to do with mysticism and occult practices.

Notwithstanding the opposition of the clergy, alchemy became very popular during the 13th and 14th century. For the first time alchemy was included into encyclopaedias, e.g. De proprietatibus rerum by Bartholomaeus Anglicus (end of 12th century), Liber de natura rerum by Thomas Cantimpratensis(1201-1262), and Speculum maior by Vincenz of Beauvais, and lots of books with sometimes very obscure recipes were circulating. Allegedly alchemy also found its way into art and literature. According to Haage the Grail in Wolfram of Eschenbach's 'Parzival' is an allegory of the lapis philosophorum. This sounds intelligible because one of the properties both shared by the Grail and the philosophers' stone is to cure all diseases. The making and multiplying of gold and silver, like in the Hellenistic days, must have been very popular and profitable. The clergy increasingly frowned on this phenomenon until in 1317 Pope John XXII. issued the bull ' Spondent quas non exhibent ' which strictly prohibited counterfeiting.

At the end of this chapter the attention should be drawn to the work of Geber latinus (end of 13th-beginning of 14th century) . It is not completely proved yet, whether he really lived or not, however in his corpus there are some ideas that cannot have been those of Djabir Ibn Hajjan, alias Geber arabicus. His view of alchemy is that of an applied natural science and he is in favour of experiments rather than mere theory. his main works are S umma perfectionis magisterii, Liber de investigatione perfectionis, and Theorica et Practica. As sources for his Summa prfectionis magisterii the following works can be identified: Rhazes Liber Secretorum de voce Bubacaris, Geber arabicus Liber divinitatis de LXX, pseudo-Rhazes De aluminibus et salibus, pseudo-Aristotle De perfecta magisteria, Avicenna De congelatione et conglutinatione lapidum, pseudo-Avicenna De re recta, and Albertus Magnus De mineralibus. From these books and apparently after own studies Geber developed a new corpuscular theory and a new transmutation theory. To him all substances consist of corpuscles of different size which make them impure. Only if the alchemist is able to bring the substances into the state of mediocris substantia, i.e. all corpuscles are of the same size, they are fit for a transmutation. His recipe for a transmutation is as follows: 1. purify Mercury and Sulphur by sublimation, 2. fix the volatile Mercury by another sublimation, 3. sublime the Sulphur with iron and copper, and 4. bring the Mercury and the Sulphur, now both in mediocris substantia, to an reaction. As can be seen, the Sal is missing, to me a fact that clearly distinguishes him from Geber arabicus. Of his predecessors he picked up the idea that Mercury is a basic component of all metals and extended it to his theory of the lapis philosophorum being pure Mercury in mediocris substantia.

Like in all epochs before also in the Middle Ages of course there circulated pseudepigraphs in abundance. Again the names of the Greek philosophers, Hermes Trismegistos, but also of contemporary scholars like Arnaldus of Villanova and Raimundus Lullus, who somewhere in their lives occupied themselves with alchemy but never published own alchemical works, were to be found under sometimes obscure books of yet more obscure recipes.

3. Alchemy in the Far East

3.1. China

Let us now leave the West and direct our attention to the cultures of the Far East. Here in China and India also and alchemistic art developed but due to some cultural and historical peculiarities unfortunately the research so far did not quite succeed to detect the real origins of Eastern alchemy.

The roots of Chinese alchemy go far back into time, although most preserved written evidences are from the first few centuries AD. It can be held that they are compilations of much older works. An especially tragic date for the historians of China was the year 213 BC when emperor Shi-Huang-Ti ordered the burning of all books he could get, except those about farming, medicine, pharmacy, tree cultivation, and fortune-telling. Fortunately soon after him in the Han-period (205 BC-220 AD) there was much effort to replace the loss but lots of gaps evidently were carelessly filled with conjectures. Surely at these times forgery was booming.

The most striking difference to Western alchemy is that the Chinese give little or no importance to the making and multiplying of gold. The main goal of Chinese alchemy is the elixir of immortality. An argument for the old age Chinese alchemy is the belief in immortality which can be traced back to the 8th century BC, as early as in the 4th century BC it was believed that it is possible to attain immortality, and finally in the 1st century BC the corresponding drug was first mentioned in a treatise as 'drinkable gold'20. The Chinese philosophy already in ancient times developed the cosmic principle of Yin and Yang, represented by the symbol [. Either bears the seed of the other and neither could be without the other. The philosophy of nature is based on the concept of five elements (Fire, Water, Wood, Earth, Metal). In older research sometimes this is ascribed to Babylonian and/or Chaldean influences but more recent studies seem to have dropped that thought. Another philosophical root of Chinese alchemy is Taoism. This philosophical-religious movement was founded in the 6th century BC by Lao- Tse and its main work is the Tao-Te-King ('classic way of power'). From the beginning on the Taoists were outsiders and soon the movement split up into a purist and mystic fraction. The latter were said to possess super- natural powers and consequently the evolving alchemy was grafted onto them. Thanks to this and a collection called 'Yün chi ch'i ch'ien' ('seven tablets in a cloudy satchel') from 1023 AD we know some more about Chinese alchemy. The book 'Tan chin yao chüeh ('great secrets of alchemy'), ascribed to a certain Sun-Ssu -Miao (581-after 673), probably is the most famous Chinese alchemical work that has come down to us. It is a practical treatise on creating elixirs for attaining immortality, using organic and mineral ingredients (Mercury, Sulphur, salts of Mercury and arsenic are mentioned), and several recipes for the cure of diseases. Because some ingredients are highly poisonous it is no surprise that several monarchs died of elixir poisoning. Both alchemists and emperors became more cautious after a whole series of such royal deaths. In the centuries to come the Chinese presumably lost interest in alchemy because alchemical texts became more and more scarce and finally ceased completely.

3.2. India and Tibet

In India and Tibet there existed a kind of alchemy that strictly speaking was no alchemy in the true sense of the word but more or less pharmacy and, to apply the Paracelsian term, iatrochemistry. Lippmann reproaches especially Indian authors for a lack of chronological thinking. He criticises that newer findings simply were included into new editions of older works. Transmutation of metals into gold plays only a very marginal role in the older texts of that region. Immortality neither was a main objective of the Indians and Tibetans because their religions already offer a way to it. In India the Hinduistic god Shiva was thought to have invented alchemy, and Mercury, first mentioned in the Artha-sastra (4th-3rd century BC), was called the 'semen of Shiva'. In the oldest Indian texts, the Sanskrit Vedas, there are hints of alchemy close to that of China, and Lippmann thinks that there were mutual influences, at least after the rise of Buddhism. In Buddhist texts of the 2nd-5th century AD there emerges the idea of transmuting base metals into gold. According to Lippmann some alchemical knowledge was 'imported' from the West because the terms and processes are strikingly similar to Greek and Arabic ones. In Northern India up to the 8th century the existence of alchemy can be verified to a certain extent by Tibetan translations of alchemical texts, found in Buddhist stupas. These texts are about panaceae and transmutations of metals. As I said above, alchemy in India in fact was pharmacy. Accordingly the Indian 'alchemists' were mainly physicians. Unfortunately there are no names mentioned because almost every Indian alchemical work was published anonymously. They created very effective remedies using the salts of the metals, either of natural sources or chemically produced, sal ammoniac, sulphur, mercury, and other minerals. As a kind of 'spin-off' they also found methods for imitating precious stones and mixing colours for dyeing and colouring of cloth and, not to forget, make-up. With the rise of Tantrism between the 12th and 14th century alchemy, then surely influenced by the Western cultures, became associated with mysticism. Since there is no written evidence for alchemy after the mid of the 14th century it can be assumed that it died out as in neighbouring China.

Concluding remarks

In Europe alchemy did not simply fade away like in Asia. On the contrary during the renaissance and later in the 16th and 17th century it reached another climax. Generations of adepts were feverishly searching for the philosophers' stone and many of them ruined themselves completely. Nevertheless important inventions and discoveries were made, for instance the discovery of the mineral acids, the aqua vitae (alcohol), the Glauber salt, new methods for the production of steel, and so on. However, there were also very many cunning deceivers who roamed the land and pretended to be able to make gold. Many monarchs had their court alchemists because they hoped for an increase in their finance. Those court alchemists sometimes led comfortable lives but in many cases they also were hanged on the infamous gilded gallows when their patrons lost patience. A good example for recipes of the 17th century is a collection published 1992 by Heiko Skerra21. Parallel to the practical branch of alchemy there developed a mystical and occult movement. Secret societies and Hermetic orders emerged and worked out an inner alchemy. The transmutation was used by them as an allegory for the process of an inner catharsis the result of which should be an enlarged consciousness and a higher self.

Selected bibliography

Alchemie und die Alchemisten. Baden-Baden: AMORC-Bücher.1993

Brockhaus Enzyklopädie in vierundzwanzig Bänden: Neunzehnte, völlig neu bearbeitete Ausgabe. Erster Band A- APT, Mannheim: Brockhaus 1986

Burckhardt, Titus: Alchemie: Sinn und Weltbild. Neudruck Andechs: Dingfelder Verlag 1993

Haage, Bernhard Dietrich: Alchemie im Mittelalter; Ideen und Bilder - von Zosimus bis Paracelsus. Zürich/Düsseldorf: Artemis und Winckler, 1996

Lippmann, Edmund O. von: Entstehung und Ausbreitung der Alchemie. Mit einem Anhange: Zur älteren Geschichte der Metalle. Hildesheim/New York: Olms 1978

Schmieder, Karl Christoph: Geschichte der Alchemie. Halle 1832, Neudruck Langen: Roller 1987 Skerra, Heiko: Alchemie, der Stein der Weisen. Rhede(Ems):Ewert 1992

The New Enzyclopædia Britannica, Volume 25. Macropædia. Enzyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Chicago/Auckland/London/Madrid/Manila/Paris/Rome/Seoul/Sydney/Tokyo/Toronto

[...]

1 In different cultures these aims were different in their importance

2 Burckhardt, Titus: Alchemie: Sinn und Weltbild, 2. Aufl., Andechs:Dingfelder Verlag 1992

3 see also Lippmann, Edmund O. von : Entstehung und Ausbreitung der Alchemie. Mit einem Anhang: Zur älteren Geschichte der Metalle. Hildesheim/New York: Olms 1978, pp 310-312

4 secret book of magic, according to a wide-spread vernacular belief each witch possesses an own copy of it5 after the names of the libraries which keep them: Leiden and Stockholm

6 cf. Haage, Berhard Dietrich: Alchemie im Mittelalter, Ideen und Bilder - von Zosimus bis Paracelsus, Zürich /Düsseldorf: Artemis und Winckler, 1996, p. 70

7 Lippmann: Entstehung und Ausbreitung der Alchemie... p. 558 8 the god of fire and the god of wisdom

9 Apophis, the incarnation of darkness, and the Mhn snake, that protects the sun-god Re from Apophis10 it became custom to put living snakes into the foundations of a new temple

11 the hydor theion (divine water, spirit of mercury ), which resurrects the black prima materia

12 see Haage: Alchemie im Mittelalter... pp. 16-17

13 special kind of alchemical oven

14 cf. Haage: Alchemie im Mittelalter... p. 110

15 as in Al-chemy, Al-embic ( from ambix), Al-embroth ( sal divinum)

16 sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic

17 'secret' in this respect meaning 'technical knowledge, know how'

18 and therefore called doctor mirabilis

19 especially see his Epistola de secretis operibus artis et naturae et nullitate magiae

20 the term aurum potabile in the West refers to / is synonymous to panacea universalis

21 Alchemie, der Stein der Weisen. Rhede(Ems): Ewert 1992

13 of 13 pages

- Quote paper

- Torsten Bock (Author), 1997, History of Alchemy from Early to Middle Ages, Munich, GRIN Verlag, https://www.grin.com/document/94692