by British Antarctic Survey

Brazilian polar vessel, NPo “Almirante Maximiano” on the West Antarctic Peninsula conducting visual surveys alongside a humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the foreground. Credit: Luciano Dalla Rosa/Universidade Federal do Rio Grande

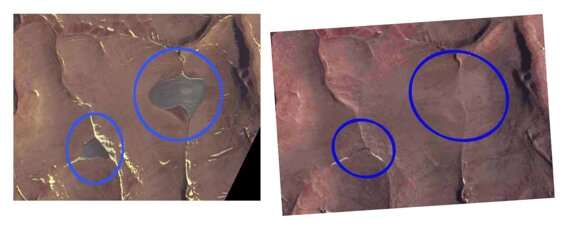

Scientists have found that studying high-resolution images of whales from space is a feasible way to estimate their populations. A team, led by British Antarctic Survey (BAS), compared satellite images to data collected from traditional ship-based surveys. Reported this week in the journal Scientific Reports, this study is a big step towards developing a cost-effective method to study whales in remote and inaccessible places, that will help scientists to monitor population changes and understand their behavior.

The results show that satellite-estimated whale densities were about a third of the densities estimated by ship. This is positive news, because it means that although satellites have poorer detection rates than ships, they still detect enough whales to make the method useful, for example for monitoring changes in whale abundance, particularly in remote regions where more expensive, traditional surveys are difficult.

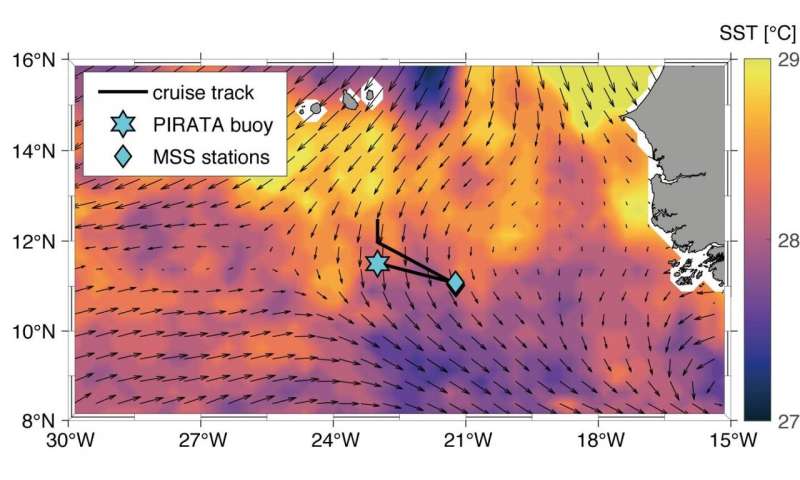

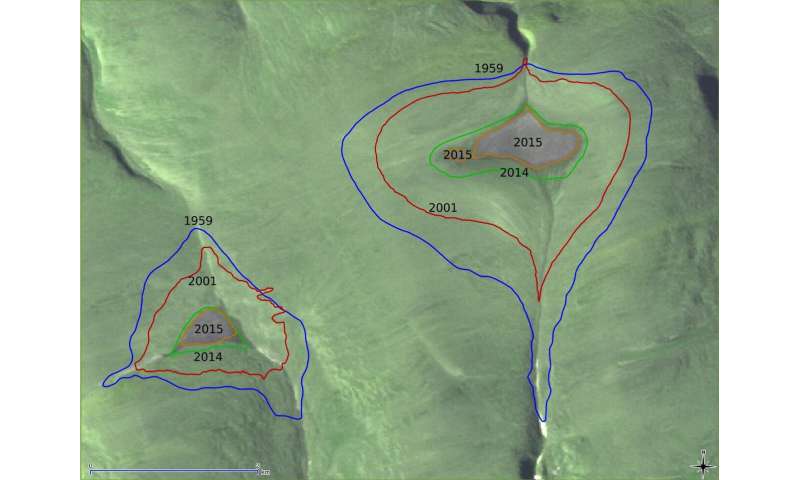

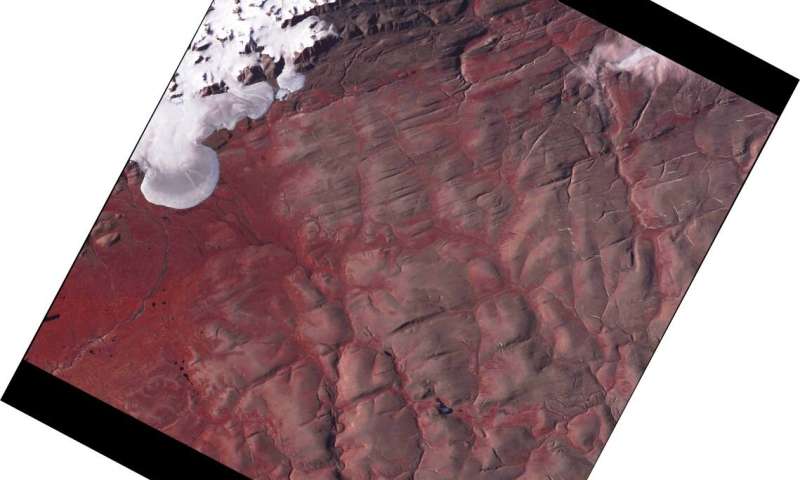

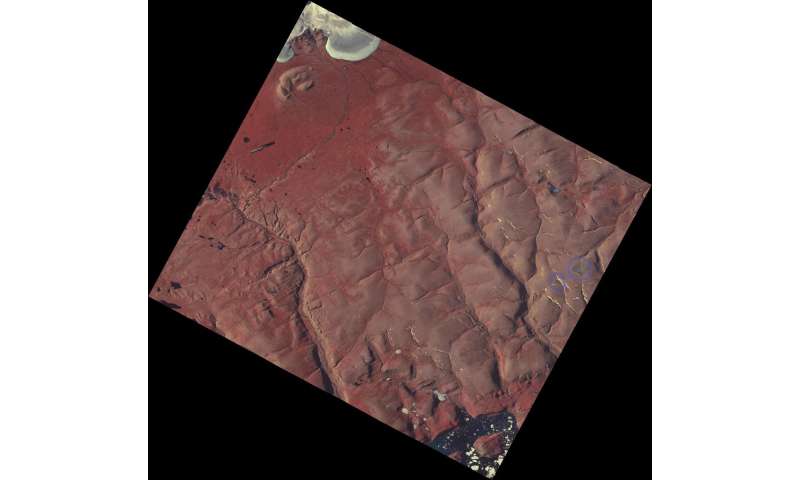

The study took place in the Antarctic Peninsula, the primary summer feeding ground for many baleen whale species. Satellite images of the Gerlache Strait region spanning ~1000 km2 were collected over two days, and compared to the Brazilian Antarctic Program's annual ship-based whale survey, taking place at a similar time.

Satellite imagery provides a viable means of gathering high volumes of whale observation data with potential for estimating whale densities at unmatched spatial and temporal scales.

Lead author, Connor Bamford, a higher-predator ecologist at BAS and University of Southampton, says:

Scientists have found that studying high-resolution images of whales from space is a feasible way to estimate their populations. A team, led by British Antarctic Survey (BAS), compared satellite images to data collected from traditional ship-based surveys. Reported this week in the journal Scientific Reports, this study is a big step towards developing a cost-effective method to study whales in remote and inaccessible places, that will help scientists to monitor population changes and understand their behavior.

The results show that satellite-estimated whale densities were about a third of the densities estimated by ship. This is positive news, because it means that although satellites have poorer detection rates than ships, they still detect enough whales to make the method useful, for example for monitoring changes in whale abundance, particularly in remote regions where more expensive, traditional surveys are difficult.

The study took place in the Antarctic Peninsula, the primary summer feeding ground for many baleen whale species. Satellite images of the Gerlache Strait region spanning ~1000 km2 were collected over two days, and compared to the Brazilian Antarctic Program's annual ship-based whale survey, taking place at a similar time.

Satellite imagery provides a viable means of gathering high volumes of whale observation data with potential for estimating whale densities at unmatched spatial and temporal scales.

Lead author, Connor Bamford, a higher-predator ecologist at BAS and University of Southampton, says:

Researchers from UC Santa Cruz deploying a motion-sensing and dive recording tag on a humpback whale off the western Antarctic Peninsula. Research conducted under NMFS Permit 23095, ACA Permit 2015-014, and IACUC Friea1706. Credit: British Antarctic Survey

"While this is a new method and we have a lot of work still to do, we hope this will pave the way for further developments that will provide a low budget means of collecting data on whales in the future. It will supplement existing efforts in remote regions, and provide information to safeguard whale populations and their remote feeding grounds."

Senior author, whale ecologist Dr. Jennifer Jackson at BAS, says:

"This new technology could be a game-changer in helping us to study whales remotely. Our study shows that satellite surveys can be a feasible method for monitoring changes in whale abundance. This approach may be especially useful in remote areas that are hard to access with ships and planes, and where densities of whales may be high, such as the Southern Ocean."

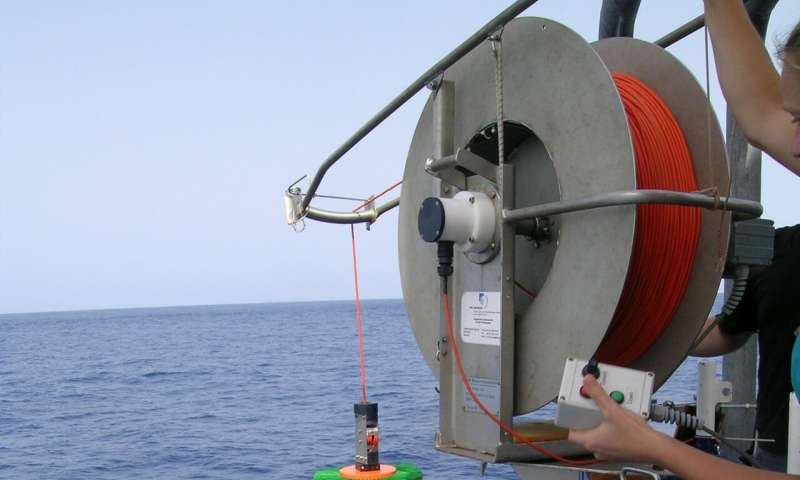

New methods offer exciting opportunities, but also need robust testing before they become operational. One issue is the ability to account for whales that are underwater. In this study researchers were able to utilize suction-cup tracking data collected by a US National Science Foundation whale tagging program that provides detailed information on dive duration and behavior of humpback whales in the waters around the Antarctic Peninsula. This accounts for those whales that were likely to be missed as a result of being underwater, beyond the depth where satellite detection is possible. Further work is now underway using machine learning tools to assist with identifying whales on satellite imagery.

"While this is a new method and we have a lot of work still to do, we hope this will pave the way for further developments that will provide a low budget means of collecting data on whales in the future. It will supplement existing efforts in remote regions, and provide information to safeguard whale populations and their remote feeding grounds."

Senior author, whale ecologist Dr. Jennifer Jackson at BAS, says:

"This new technology could be a game-changer in helping us to study whales remotely. Our study shows that satellite surveys can be a feasible method for monitoring changes in whale abundance. This approach may be especially useful in remote areas that are hard to access with ships and planes, and where densities of whales may be high, such as the Southern Ocean."

New methods offer exciting opportunities, but also need robust testing before they become operational. One issue is the ability to account for whales that are underwater. In this study researchers were able to utilize suction-cup tracking data collected by a US National Science Foundation whale tagging program that provides detailed information on dive duration and behavior of humpback whales in the waters around the Antarctic Peninsula. This accounts for those whales that were likely to be missed as a result of being underwater, beyond the depth where satellite detection is possible. Further work is now underway using machine learning tools to assist with identifying whales on satellite imagery.

More information: C. C. G. Bamford et al. A comparison of baleen whale density estimates derived from overlapping satellite imagery and a shipborne survey, Scientific Reports (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-69887-y

Journal information: Scientific Reports

Provided by British Antarctic Survey