Past tropical forest changes drove megafauna and hominin extinctions

by Max Planck Society

Artist's reconstruction of a savannah in Middle Pleistocene Southeast Asia. In the foreground Homo erectus, stegodon, hyenas, and Asian rhinos are depicted. Water buffalo can be seen at the edge of a riparian forest in the background Credit: Peter Schouten

In a paper published today in the journal Nature, scientists from the Department of Archaeology at MPI-SHH in Germany and Griffith University's Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution have found that the loss of southeast Asian grasslands was instrumental in the extinction of many of the region's megafauna, and probably of ancient humans too.

"Southeast Asia is often overlooked in global discussions of megafauna extinctions," says Associate Professor Julien Louys, who led the study, "But in fact, it once had a much richer mammal community full of giants that are now all extinct."

By looking at stable isotope records in modern and fossil mammal teeth, the researchers were able to reconstruct whether past animals predominately ate tropical grasses or leaves, as well as the climatic conditions at the time they were alive. "These types of analyses provide us with unique and unparalleled snapshots into the diets of these species and the environments in which they roamed," says Dr. Patrick Roberts of the MPI-SHH, the other corresponding author of this study.

The researchers compiled these isotope data for fossil sites spanning the Pleistocene, the last 2.6 million years, as well as adding over 250 new measurements of modern Southeast Asian mammals representing species that had never before been studied in this way.

They showed that rainforests dominated the area from present-day Myanmar to Indonesia during the early part of the Pleistocene but began to give way to more grassland environments. These peaked around 1 million years ago, supporting rich communities of grazing megafauna such as the elephant-like stegodon that, in turn, allowed our closest hominin relatives to thrive. But while this drastic change in ecosystems was a boon to some species, it also lead to the extinction of other animals, such as the largest ape ever to roam the planet: gigantopithecus.

In a paper published today in the journal Nature, scientists from the Department of Archaeology at MPI-SHH in Germany and Griffith University's Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution have found that the loss of southeast Asian grasslands was instrumental in the extinction of many of the region's megafauna, and probably of ancient humans too.

"Southeast Asia is often overlooked in global discussions of megafauna extinctions," says Associate Professor Julien Louys, who led the study, "But in fact, it once had a much richer mammal community full of giants that are now all extinct."

By looking at stable isotope records in modern and fossil mammal teeth, the researchers were able to reconstruct whether past animals predominately ate tropical grasses or leaves, as well as the climatic conditions at the time they were alive. "These types of analyses provide us with unique and unparalleled snapshots into the diets of these species and the environments in which they roamed," says Dr. Patrick Roberts of the MPI-SHH, the other corresponding author of this study.

The researchers compiled these isotope data for fossil sites spanning the Pleistocene, the last 2.6 million years, as well as adding over 250 new measurements of modern Southeast Asian mammals representing species that had never before been studied in this way.

They showed that rainforests dominated the area from present-day Myanmar to Indonesia during the early part of the Pleistocene but began to give way to more grassland environments. These peaked around 1 million years ago, supporting rich communities of grazing megafauna such as the elephant-like stegodon that, in turn, allowed our closest hominin relatives to thrive. But while this drastic change in ecosystems was a boon to some species, it also lead to the extinction of other animals, such as the largest ape ever to roam the planet: gigantopithecus.

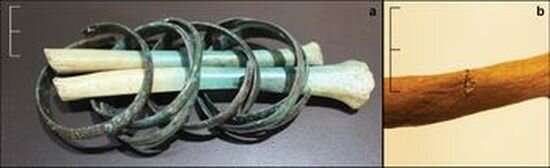

A collection of mammal skulls of species endemic to Southeast Asia. Credit: Julien Louys

However, as we know today, this change was not permanent. The tropical canopies began to return around 100,000 years ago, alongside the classic rainforest fauna that are the ecological stars of the region today.

The loss of many ancient southeast Asian megafauna was found to be correlated with the loss of these savannah environments. Likewise, ancient human species that were once found in the region, such as Homo erectus, were unable to adapt to the re-expansion of forests.

"It is only our species, Homo sapiens, that appears to have had the required skills to successfully exploit and thrive in rainforest environments," says Roberts. "All other hominin species were apparently unable to adapt to these dynamic, extreme environments."

However, as we know today, this change was not permanent. The tropical canopies began to return around 100,000 years ago, alongside the classic rainforest fauna that are the ecological stars of the region today.

The loss of many ancient southeast Asian megafauna was found to be correlated with the loss of these savannah environments. Likewise, ancient human species that were once found in the region, such as Homo erectus, were unable to adapt to the re-expansion of forests.

"It is only our species, Homo sapiens, that appears to have had the required skills to successfully exploit and thrive in rainforest environments," says Roberts. "All other hominin species were apparently unable to adapt to these dynamic, extreme environments."

Modern day rainforest in Southeast Asia. Credit: Julien Louys

Ironically, it is now rainforest megafauna that are most at risk of extinction, with many of the last remaining species critically endangered throughout the region as a result of the activities of the one surviving hominin in this tropical part of the world.

"Rather than benefitting from the expansion of rainforests over the last few thousand years, Southeast Asian mammals are under unprecedented threat from the actions of humans," says Louys. "By taking over vast tracts of rainforest through urban expansion, deforestation and overhunting, we're at risk of losing some of the last megafauna still walking the Earth."

Explore further Seeking ancient rainforests through modern mammal diets

Ironically, it is now rainforest megafauna that are most at risk of extinction, with many of the last remaining species critically endangered throughout the region as a result of the activities of the one surviving hominin in this tropical part of the world.

"Rather than benefitting from the expansion of rainforests over the last few thousand years, Southeast Asian mammals are under unprecedented threat from the actions of humans," says Louys. "By taking over vast tracts of rainforest through urban expansion, deforestation and overhunting, we're at risk of losing some of the last megafauna still walking the Earth."

Explore further Seeking ancient rainforests through modern mammal diets

More information: Environmental drivers of megafauna and hominin extinction in Southeast Asia, Nature (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2810-y ,

Journal information: Nature

Provided by Max Planck Society