UK Rwanda asylum plan against international law, says UN refugee agency

By Doug Faulkner & Joseph Lee

BBC News

PA MEDIA

PA MEDIAPlans to send some asylum seekers from the UK to Rwanda are a breach of international law, the UN's refugee agency has said.

The UNHCR said attempting to "shift responsibility" for claims of refugee status was "unacceptable".

Boris Johnson has said he believes the scheme complies with international law.

Meanwhile, it has emerged that Priti Patel issued a "ministerial direction" to launch the policy amid concerns from Home Office civil servants.

Civil servants could not precisely quantify the benefits of the policy and uncertainty about the costs meant the home secretary had to take personal responsibility for it by issuing the direction.

A source close to Ms Patel said that "deterring illegal entry would create significant savings" and the fact that the savings could not be quantified precisely should not prevent action from being taken.

Ministerial directions have been used 46 times since the 2010 election, with two in the Home Office since 1990, according to the Institute for Government think tank.

The only other time the formal order was used by the Home Office was in 2019 by the former home secretary Sajid Javid, to bring in the Windrush Compensation Scheme before legislation was in place.

Under the £120m scheme, people deemed to have entered the UK unlawfully since 1 January could be flown to Rwanda, where they will be allowed to apply for the right to settle in the east African country.

The government said the first flights could begin within weeks, initially focusing on single men who crossed the Channel in small boats or lorries.

More than 160 charities and campaign groups have urged the government to scrap the plan, while opposition parties and some Conservatives have also criticised the policy.

Gillian Triggs, an assistant secretary-general at the UNHCR, told BBC Radio 4's the World At One programme the agency strongly condemned "outsourcing" the responsibility of considering refugee status to another country.

A former president of the Australian Human Rights Commission, she said such policies - as used in Australia - could be effective as a deterrent but there were "much more legally effective ways of achieving the same outcome".

Australia has used offshore detention centres since 2001, with thousands of asylum seekers being transferred out of the country since then.

It has been frequently criticised by the UN and rights groups over substandard conditions at its centres and its own projections show it will spend $811.8m (£460m) on offshore processing in 2021-22.

Ms Triggs pointed out Israel had attempted to send Eritrean and Sudanese refugees to Rwanda, but they "simply left the country and started the process all over again".

"In other words, it is not actually a long-term deterrent," she said.

Shadow justice minister Ellie Reeves called the policy "unworkable" and said if Labour was in charge, it would make it illegal to advertise people smuggling on social media and work more closely with France and others to tackle trafficking gangs.

Just another risk to factor in

By Jessica Parker, at a camp in Dunkirk, northern France

No-one we initially spoke to yesterday seemed to know about the Rwanda announcement - but it wasn't long before word spread.

Soon a group of men was asking us lots of questions: "When will this happen? Why? If I come from Afghanistan will it still apply to me?"

Shafi, who told me he had fled Afghanistan, said: "[Rwanda] is a lot worse place than Afghanistan, there is no future for us in Rwanda."

But I didn't meet anyone who said the government's plans would prevent them from trying to cross the Channel, including Shafi, who said he had no choice.

Many of these men have already faced huge risks to get this far and are willing to risk their lives crossing the Channel on a small boat.

The risk of being sent to Rwanda, at this stage, seemed like just another thing to factor in down the line.

A number of lawyers have warned the plan will face legal obstacles, such as the international human rights principle of "non-refoulement" - which guarantees no one can be returned to a country where they would face irreparable harm.

Last year, the UK government raised concerns at the UN about allegations of "extrajudicial killings, deaths in custody, enforced disappearances and torture" in Rwanda, as well as restrictions to civil and political rights.

But justice and migration minister Tom Pursglove said Rwanda was a progressive country that wanted to provide sanctuary and had made "huge strides forward" in the past three decades.

And a Home Office spokesperson added: "Rwanda will process claims in accordance with the UN Refugee Convention, national and international human rights laws, and will ensure their protection from inhuman and degrading treatment or being returned to the place they originally fled. There is nothing in the UN Refugee Convention which prevents removal to a safe country."

Ms Patel said the British public had been "crying out for change for years" and it was "incredibly unfair to the British public to see organisations in their own country effectively just putting blockages after blockages in the way".

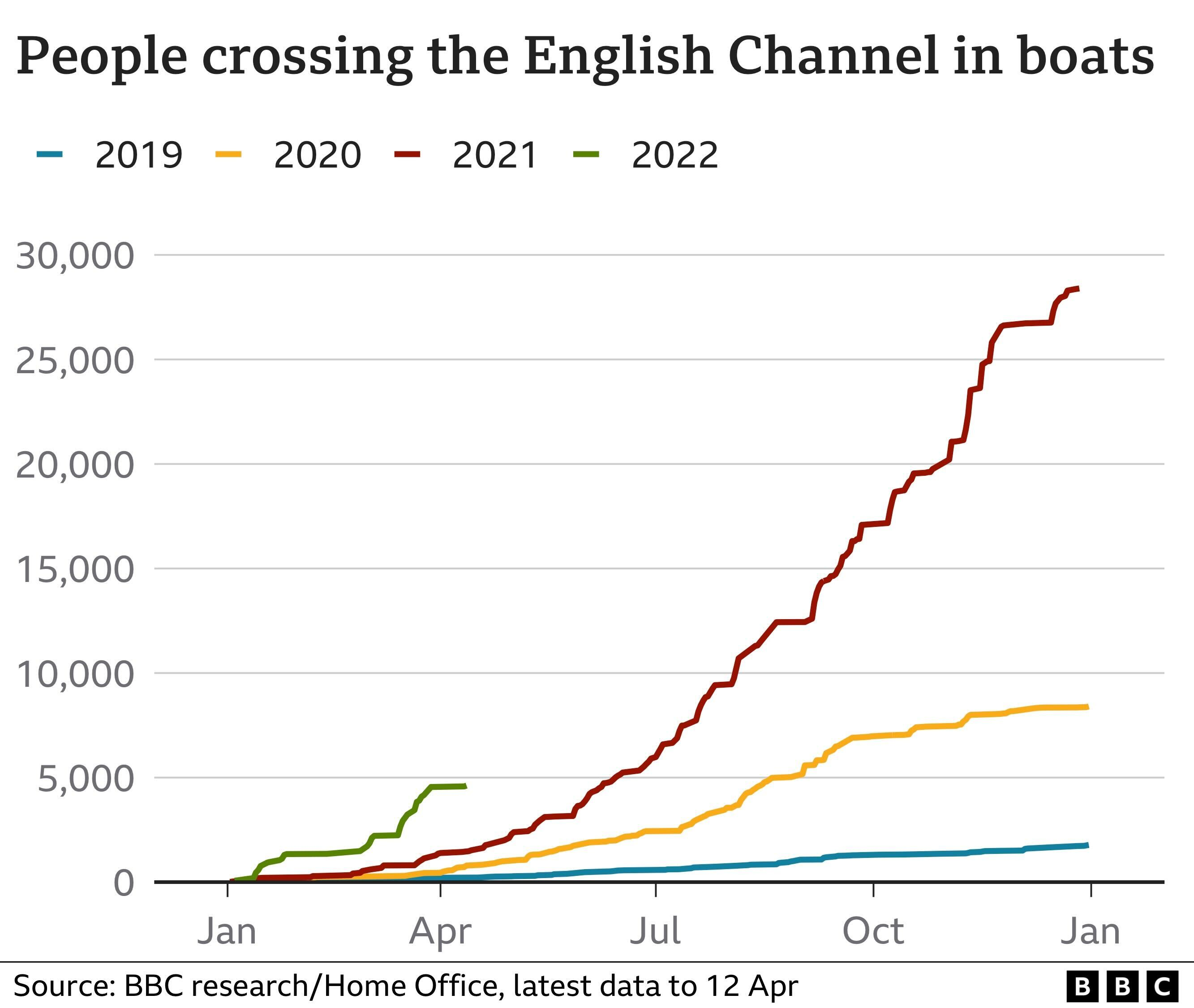

The announcement came as part of a broader strategy to reduce the number of people entering the UK by crossing the Channel in small boats.

The Royal Navy has taken operational command of the Channel from UK Border Force in an effort to detect every boat headed to the UK.

Some 562 people on 14 boats made the journey on the day the new scheme was announced, according to the Ministry of Defence. No-one making the crossing was believed to have arrived on UK soil "on their own terms", it added.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/Y3E6JON37JARHCMMMFCGROCSXU.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/T64M3K2MZRHWNPYG3XQH4SYKQI.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/4MCIYPQ3Z5FDPDVVB7FVONHRQA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/NSJIVRSNRRCNBBZJS4K4S4Q2AU.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/70713407/EW_big_tech_wwa_board2.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23369058/GettyImages_1152669075_copy.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23369083/GettyImages_1238162825_copy.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23369099/GettyImages_1347942953_copy.jpg)