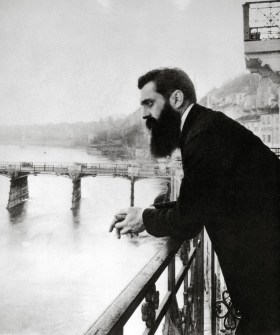

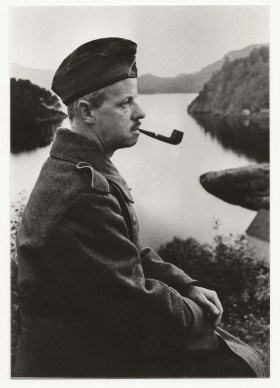

The Führer’s forgotten poet

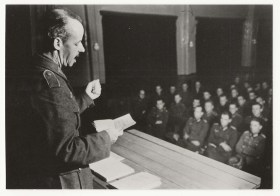

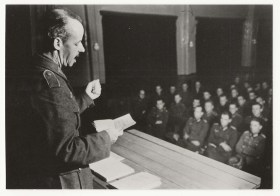

Anacker (centre) in SA uniform during a Nazi Party meeting;

the photo is probably from 1939.

Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach

History has not looked kindly on the legacy of Swiss poet Heinrich Anacker, whose books became best-sellers in Nazi Germany. A look at a controversial man of letters who the Nazi Party called “a singer of our times”.

This content was published on September 7, 2022

Alexander Thoele

The life of Heinrich Anacker, Switzerland’s most-read poet of the 20th century, came to a tragic end on January 14, 1971, when he tripped on an icy road while out for a walk in Wasserburg on Lake Constance. He hit his head on the asphalt and suffered a stroke.

Upon his death, not a single obituary appeared in the newspapers. The world seemed almost relieved at his passing. His name sank into oblivion, as did his poems, many of which he wrote in honour of Adolf Hitler.

Anacker had certainly worked hard for his fame. He was known as the “Poet of the Movement”, “Lyricist of the Brown Front” or even “Poet of the Storm Troopers”. He was a productive writer. By the end of the Second World War, he had published 22 poetry volumes in Germany and sold 180,000 copies of them.

Several of his poems were used in military marches, such as From Finland to the Black Sea, which glorified Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany in 1941.

Anacker was born on January 29, 1901, in the village of Buchs in canton Aargau. His parents owned a printing business and a packaging factory. His father, Georg Anacker, was originally from the German town of Leipzig but took on Swiss citizenship in 1917, which he transferred to his son.

In 1921, one year before graduating from high school, Anacker published his first poem, Klinge, kleines Frühlingslied, through a small local publishing house. That year, he met the local baker’s daughter Emmy, who later became his wife.

Anacker and his wife in their newly-built house in Wannsee, near Berlin, 1937-1938. Arquivo pessoal de Charles Linsmayer

First contact with Nazis

In an interview with the Swiss literature critic and journalist Charles Linsmayer in 1984, Emmy said that she had fallen in love with a young poet who was passionate about nature and beautiful feelings and came from “a decent family”.

After he graduated from high school, Anacker enrolled at the University of Zurich to study literature and philosophy. But in 1923 he interrupted his studies to move to Vienna, where he continued his education and joined a conservative student fraternity. That’s when Anacker first came into contact with the Nazis.

Two years later, he returned to Zurich and reunited with his wife, but the National Socialists did not cease to fascinate him. He was so enthralled with them that in 1927 he travelled to Germany to attend the Nuremberg Rallies, the national event of the Nazi Party.

“When he heard Hitler speak for the first time, he was very impressed,” Emmy told Linsmayer. “He said to me: ‘This is the man who will save Germany’.” Emmy had studied drama and found a job in Döbeln in the German state of Saxony, where she relocated in 1928. Anacker then abandoned his studies and followed his wife to Germany.

Later that year, he joined the Nazi Party’s local group with the assigned membership number 105,290, and soon afterwards enlisted with the Storm Troopers. His poems were not yet tainted by National Socialism and were not unsuccessful.

In 1932, Anacker’s first volume of political poetry, The Drum, was published by the Storm Troopers’ own publishing house. In this collection, Anacker switched gears, writing about the changes the country was going through.

“The fascist revolution had found its way to Germany assisted by the rhythm of Anacker’s songs and lyrics, which were a skillfull mix of political indoctrination, aggression and praise for nature,” said Linsmayer. “They brainwashed the minds of the Germans.”

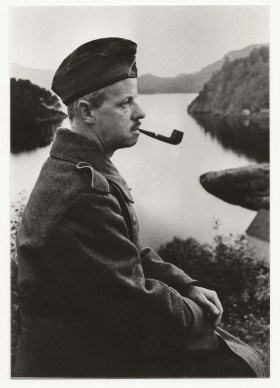

During his years in the German army, Anacker visited various parts of the front and recited poetry to the soldiers, such as here in Norway, 1942.

Acervo privado de Charles Linsmayer

‘A singer of our times’

In Germany, Anacker rubbed shoulders with Nazi writers and intellectuals, among them high-ranking officials such as Julius Streicher, the regional leader of the Nazi Party and founder and publisher of the antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer. He became reasonably well-known through these contacts, and when he met Hitler in a railway carriage in 1933, the Führer allegedly said to him: “Ah, you are Anacker.”

It did not take long for the Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, to arrange meetings with Anacker so they could discuss literature and ways his lyrics could be used in military marches.

During the Nuremberg Rallies in 1936, Anacker received the National Prize for Art and Science, handed to him by Hitler’s chief ideologue, Alfred Rosenberg. “For many years, Storm Trooper Anacker’s poetry has accompanied our movement,” the Nazi Party stated in awarding him the prize. “As a singer of our times, he lifted our spirits and wrote powerful but sad songs that described our yearnings.”

At the start of the Second World War, Anacker decided to give up his Swiss citizenship. “I was born German but lost my German nationality through my father’s naturalisation in Switzerland,” he wrote to the German authorities after the war. “This was against my will. I have always been German at heart.”

The war did not blight Anacker’s passion for poetry. From 1938 to 1945, he published a spate of poetry volumes, such as Ein Volk - ein Reich - ein Führer (One People, One Realm, One Leader, 1938), Wir wachsen in das Reich hinein (We Grow into the Realm, 1938) and Marsch durch den Osten (March Through the East, 1943). All of these works were printed by the Nazi Party's central publishing house whose biggest success was the publication of Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

Anacker, in German military attire, pictured in occupied Norway in September 1944. Arquivo pessoal de Charles Linsmayer

A poet in uniform

In 1941, Anacker was conscripted into the Wehrmacht, Nazi Germany’s unified forces. But despite the lack of soldiers due to difficulties on the various fronts, the armed forces allowed Anacker to continue his paid duty as the party’s poet. In his corporal uniform, he recited his poetry before the troops, visiting them in France, Russia and occupied Norway in 1944. He then wrote about these experiences. When it became clear that the war would soon be lost, Anacker was transferred to a military hospital, where he looked after the wounded.

On April 23, 1945, the American army arrested Anacker in Bavaria and imprisoned him there until the end of that year. When he was released, he could not return to his house in Berlin as it was occupied by the Russians. He moved in with relatives in Salach, a village in southern Germany.

Denazification did not affect Anacker. In 1948 the district court in the German town of Göppingen sentenced him to six months in prison for his role as a collaborator. However, one year later, the higher regional court of the state of Baden-Württemberg cut his sentence and classified him as a passive follower or, to use the German term, a Mitläufer.

During the hearings, Anacker testified that he had had no clue about the horrors committed by the Nazis.

In 1955, Heinrich and Emmy Anacker moved to Wasserburg on the shores of Lake Constance where they had a view of Switzerland. Since he had given up Swiss citizenship, Anacker no longer had any connections with his old homeland, and not even with the Nazi movement in Switzerland.

Persona non grata

This disconnection was not voluntary. Official documents show that Anacker applied for several entry visas, stating that he had to visit his sick parents or parents-in-law or to deal with inheritance matters. Most of his applications were rejected.

In 1951, Anacker printed a few copies of his final book, Goldener Herbst (Golden Autumn). He did not publish it to make money as he had become financially independent thanks to an inheritance from his parents. He could even afford a secretary, who typed and archived his work. He continued to write until his death. Thousands of poems were carefully kept in wooden boxes that are now stored in the German Literature Archive in Marbach, following a long legal battle with a right-wing extremist association. Most of his works were never read or published.

Translated from German by Billi Bierling/gw