After Roe Fell: Abortion Laws by State

With the overturn of Roe v. Wade by the U.S. Supreme Court in June 2022, abortion policies and reproductive rights are in the hands of each state.

Use this map to explore the breakdown of abortion laws by state in real-time–and understand abortion bans, types of abortion restrictions, what trigger bans are, and more.

Glossary

Understanding Abortion Bans

Pre-Roe bans

Most states repealed abortion bans in effect as of 1973 once Roe made them unenforceable. However, some states and territories never repealed their pre-Roe abortion bans. Now that the Supreme Court has overturned Roe, these states could try and revive these bans.

Trigger bans

Abortion bans passed since Roe was decided that are intended to ban abortion entirely if the Supreme Court limited or overturned Roe or if a federal Constitutional amendment prohibited abortion.

Pre-viability gestational bans

Laws that prohibit abortion before viability; these laws were unconstitutional under Roe. Gestational age is counted in weeks either from the last menstrual cycle (LMP) or from fertilization.

Method bans

Laws that prohibit a specific method of abortion care, most commonly dilation and extraction (D&X) procedures and dilation and evacuation (D&E) procedures.

Reason bans

Laws that prohibit abortion if sought or potentially sought for a particular reason. These bans typically name sex, race, and genetic anomaly as prohibited reasons. However, there is no evidence that pregnant people are seeking abortion care because of the sex or race of their fetus.[1].

Criminalization of self-managed abortion (SMA)

Some states criminalize people who self-manage their abortion, i.e., end their pregnancies outside of a health care setting.

SB-8 Copycats

Laws that are modeled after Texas SB 8, the vigilante law that took effect in September 2021. These laws ban abortion at an early gestational age and are enforced through private rights of action, which authorizes members of the public to sue abortion providers and people who help others access abortion care.

Types of Abortion Restrictions

Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers (TRAP)

Targeted regulation of abortion providers (TRAP) laws single-out physicians who provide abortion care and impose various legal requirements that are different from and more burdensome than those imposed on physicians who provide comparable types of care. These laws do not increase patient safety and are counter to evidence-based clinical guidelines. [2]

TRAP laws fall into several categories, including regulation of locations where abortion is provided and/or facility specifications, provider qualifications, and reporting requirements. Compliance is often costly and can require unnecessary facility modifications.

Parental involvement

Laws that require providers or clinics to notify parents or legal guardians of young peoples seeking abortion prior to an abortion (parental notification) or document parents’ or legal guardians’ consent to a young person’s abortion (parental consent).

Consent laws

Laws that require pregnant people to receive biased and often inaccurate counseling or an ultrasound prior to receiving abortion care, and, in some instances, to wait a specified amount of time between the counseling and/or ultrasound and the abortion care. These laws serve no medical purpose but, instead, seek to dissuade pregnant people from exercising bodily autonomy.

Hyde Amendment

In 1976, Rep. Henry Hyde (R-IL) successfully introduced a budget rider, known as the Hyde Amendment, that prohibits federal funding for abortion. Congress has renewed the Hyde Amendment every year since its introduction.

Abortion Protections

Statutory protections for abortion

Laws passed by states that protect the right to abortion.

State constitutional protection

A declaration from the state’s highest court affirming that the state constitution protects the right to abortion, separately and apart from the existence of any federal constitutional right.

Abortion Access

Public funding

States are required to provide public funding through the state Medicaid program for abortion care necessitated by life endangerment, rape, or incest. States can also dedicate state-only funding to cover all or most medically necessary abortion care for Medicaid recipients.

Private insurance requirements

States can require private health-insurance plans that are regulated by the state to contain specific benefits, including abortion coverage.

Clinic safety and access

Laws that prohibit, for example, the physical obstruction of clinics, threats to providers or patients, trespassing, and telephone harassment of the clinic, and/or create a protected zone around the clinic.

Abortion Provider Qualifications

Scope of practice for health-care practitioners is regulated by state legislatures and licensing boards. Generally, state legislation does not outline specific medical care that is within or beyond a practitioner’s scope of practice. However, many states have treated abortion differently by restricting the provision of abortion to physicians. Other states have taken proactive measures to expand the types of clinicians who may lawfully provide abortion care by repealing physician-only laws or expressly authorizing physician assistants, certified nurse midwives, nurse practitioners, and other qualified medical professionals to provide abortion care through legislation, regulations, or attorney general opinions.[3]

Interstate Shield

States hostile to abortion have made it clear that they want to prohibit abortion entirely, both inside and outside of their borders. Interstate shield laws protect abortion providers and helpers in states where abortion is protected and accessible from civil and criminal consequences stemming from abortion care provided to an out-of-state resident.

In effect

A law has been enacted, and the effective date in the legislation has passed.

Enjoined

The state cannot enforce a law that would otherwise be effective because of the decision by a court to temporarily or permanently enjoin its enforcement.

Project Summary

Initially, this tool provided an overview of what could happen to abortion rights in the fifty states, the District of Columbia, and the five most populous U.S. territories if the U.S. Supreme Court were to limit or overturn Roe v. Wade, the landmark Supreme Court ruling from 1973 that established abortion as a fundamental right. Now rebranded as U.S. Abortion Laws by state, this digital tool describes the abortion policy of the U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and the five most populous U.S. territories, which requires careful legal analysis of constitutions, laws, regulations, and court decisions. This online tool charts how these governments are responding to the reversal of Roe.

Methodology

To determine into which category to place each state, D.C., and the U.S. territories, we first examined whether the right to abortion is protected under state, territory, or D.C. law (“Protected”); if it is, we looked to see whether the state, territory, or District of Columbia enacted laws or policies that enhanced access to abortion care (“Enhanced Access”). If abortion is not protected by state or territory law (“Not Protected”), we then looked to see if the government enacted laws or policies to restrict or prohibit access to abortion care (“Hostile”). Finally, we examined states that have criminalized abortion and prohibited it entirely (“Illegal”). Based on our analysis, we then placed each state, territory, and the District of Columbia into one of these five categories, which exist along a spectrum from “Expanded Access” to “Protected” to “Not Protected” to “Hostile” and, finally, to “Illegal.”

The laws and policies identified as creating enhanced access to abortion include public funding and the requirement that abortion be included in private insurance coverage, unrestricted access for young people, the breadth of health-care practitioners who provide abortion care, and protections for clinic safety and access. We assessed hostility and illegality based on abortion bans (pre-Roe, trigger, gestational, reason, method, SB8 copycats, and criminalization of self-managed abortion) and abortion restrictions (TRAP, parental involvement, consent, and physician-only laws). While these bans and restrictions generally have exceptions, this tool does not list them in detail because those exceptions do not provide meaningful access and usually are difficult to utilize. Unless otherwise noted, all bans and restrictions discussed are in effect.

Findings

Today, abortion is protected by state law in 21 states and the District of Columbia and is at risk of being severely limited or prohibited in twenty-six states and three territories.

States Where Abortion Is Protected

Expanded Access

The “Expanded Access” category means that the right to abortion is protected by state statutes or state constitutions, and other laws and policies have created additional access to abortion care.

Protected

Moving across the spectrum, the “Protected” category means that the right to abortion is protected by state law but there are limitations on access to care

States Where Abortion Is Not Protected

Not Protected

The “Not Protected” category means that abortion may continue to be accessible in these states and territories, but would be unprotected by state and territory law. In some of these states, it is unclear whether the legislature would enact a ban now that Roe has been overturned, but concern is warranted.

Hostile

The “Hostile” category means that these states and territories have expressed a desire to prohibit abortion entirely. These states and territories are extremely vulnerable to the revival of old abortion bans or the enactment of new ones, and none of them has legal protections for abortion.

Illegal

Finally, after the Supreme Court overruled Roe v. Wade, states that ban abortion entirely and enforce those bans through criminal penalties are characterized as “Illegal.”

What Did Roe v. Wade Protect Besides Abortion?

Since Roe, the Supreme Court has repeatedly reaffirmed that the Constitution protects for abortion as an essential liberty, which is tied to other liberty rights to make personal decisions about family, relationships, and bodily autonomy. It’s important to understand all of the Rights the Roe v. Wade had protected before it was recently overturned.

Roe v. Wade was Overturned and Reproductive Rights are At Risk

By overturning Roe v. Wade, which for nearly 50 years protected the federal Constitutional right to abortion, the the Supreme Court gave states total leeway to restrict abortion or prohibit it all together. Almost half the states are likely to enact new laws as restrictive as possible or seek to enforce current, unconstitutional laws prohibiting abortion. We are seeing states divide into abortion deserts, where it is illegal to access care, and abortion havens, where care continues to be available. Millions of people living in abortion deserts, mainly in the South and Midwest, are forced to travel to receive legal care, which results in many people simply being unable to access abortion for a variety of financial and logistical reasons. It is critical that “Not Protected” states create a state right to abortion, and that the “Protected” states enact laws and policies that move them into “Expanded Access.”

References

| ↑1 | Bonnie Steinbock, Preventing Sex-Selective Abortions in America: A Solution in Search of a Problem, The Hasting Center (2017) |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See, e.g., ACOG, Increasing Access to Abortion (Nov. 2014, reaffirmed 2019); National Abortion Federation, Clinical Policy Guidelines for Abortion Care (2018) |

| ↑3 | See, e.g., Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 22, § 1598(1). Law was amended to allow physician assistants and advanced practice nurses to also perform abortions. See H.P. 922, 129th Leg., 1st Reg. Sess. (Me. 2019); Wash. Rev. Code § 9.02.110; Wash. Att’y Gen. Op 2004 No. 1 (2004); Wash. Att’y Gen. Op 2019 No. 1 (2019). |

Medbrief

States With Stricter Abortion Laws Saw Fewer Ob/Gyn Residency Applicants

Brittany Vargas

February 08, 2024

TOPLINE:

States with abortion bans or gestational limits are seeing a small but statistically significant decrease in the percentage of applicants to ob/gyn residencies, according to a new study published in JAMA Network Open.

METHODOLOGY:

Most residents go on to work in the same state as their program, so any decrease in the number of students a given institution could affect access to care in that region later on.

Using data from the Association of American Medical Colleges Electronic Residency Application Service, researchers examined changes in the percentage of all US applicants to ob/gyn residency programs between 2019 and 2023.

They focused on differences in application numbers among states with varying abortion laws after the 2022 Dobbs v Jackson decision.

A secondary analysis was conducted of "program signaling," in which applicants indicated their top and secondary choices in residencies; this preference program was implemented for 2022 applications, the same year as the Supreme Court decision, so only 1 year of signaling data was available.

The percentage of MD applicants coming from states without bans applying to programs in states with complete bans decreased from 79.2% in 2021 to 73.3% in 2022.

Using the 1 year of program signaling data, researchers found no significant difference in applicants' preferences for programs in states with and those without abortion laws.

IN PRACTICE:

"The findings suggest early evidence of a decline in the number of unique applicants to ob/gyn residency programs in states with strict abortion laws," the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Maya M. Hammoud, MD, research professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor. It was published online on February 7, 2024.

LIMITATIONS:

Actions by states in terms of various laws and regulations on abortion were often appealed in courts, so applicants may either have been not aware of or confused by the implications for clinical practice. People could send applications or program signals to multiple programs, which may have affected the data.

DISCLOSURES:

Hammoud reports receiving fees from the American Medical Association (AMA) for consulting with the Medical Education Business unit outside the submitted work. The study was funded by a grant from the AMA

January 2023

Reproductive rights are under attack. Will you help us fight back with facts?

Donate

Note: This resource is not updated with the most recent policy and legal developments. See our interactive map for the latest state abortion policies in effect.

As of September 1, 2023, updates include total abortion bans in Indiana and North Dakota, a six-week ban in South Carolina, and 12-week bans in North Carolina and Nebraska. Bans have been blocked in Iowa, Utah and Wyoming. Also, the Montana State Supreme Court ruled that the state constitution protects abortion rights, and an abortion ban passed by the legislature will not go into effect as long as the constitution is not amended.

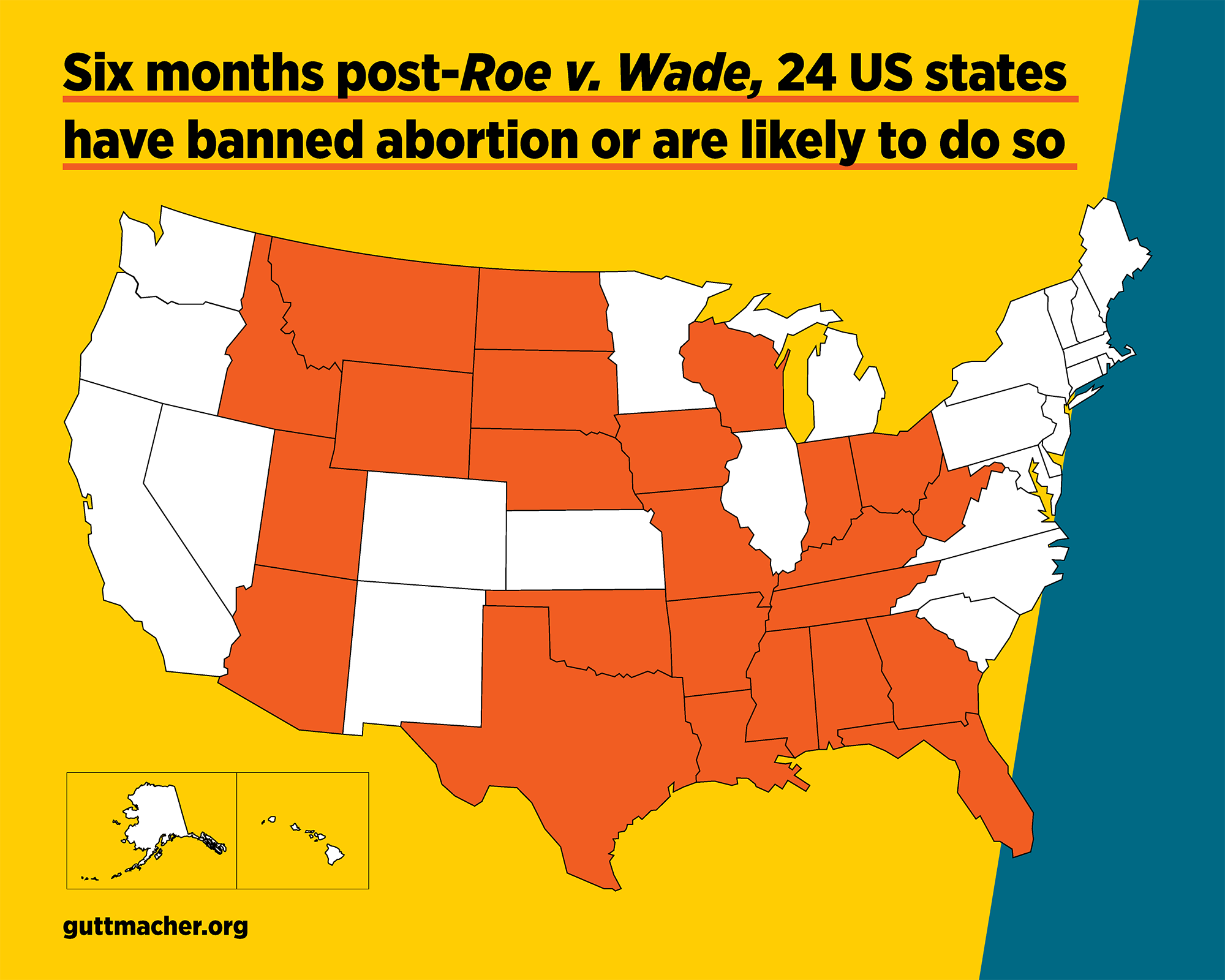

Since the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June 2022, the legal landscape on abortion has shifted dramatically.

Many states have passed near-total bans on abortion with very limited exceptions or banned the procedure early in pregnancy. Courts have blocked some of these bans from taking effect, ushering in a chaotic legal landscape that is disruptive for providers trying to offer care and patients trying to obtain it.

The developments since Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization was decided support our initial analysis from October 2021 predicting that 26 states were certain or likely to ban abortion in the absence of Roe—with two exceptions, Michigan and South Carolina.

Michigan was included as a state certain to ban abortion because it had not repealed its pre-Roe abortion ban. However, in the November 2022 elections, Michigan voters overwhelmingly approved an amendment to the state constitution protecting abortion rights, making it virtually impossible for the pre-Roe ban to go into effect.

South Carolina was considered certain to ban abortion because it had enacted a six-week abortion ban in 2021. However, the South Carolina Supreme Court struck down that ban in January 2023, holding that the right to privacy in the state’s constitution includes the right to an abortion. A majority of lawmakers in the South Carolina legislature remain opposed to abortion rights and may consider another gestational age ban in the future, but the state is unlikely to adopt a ban before six weeks of pregnancy.

These victories bring the number of states that have already banned abortion or are likely to do so down from 26 to 24—still a staggering number that means millions of people are being denied the right to bodily autonomy and access to critical health care. When people do not have access to abortion care in their state, they are forced to make the difficult decision to travel long distances for care, self-manage an abortion or carry an unwanted pregnancy to term.

Here’s where abortion bans and restrictions stand in these 24 states and what we’re expecting in the months to come, as states enter the first legislative sessions in 50 years without Roe:

States Where Abortion Is Banned

As of January 9, 2023, 12 states are enforcing a near-total ban on abortion with very limited exceptions. In five of these states, the ban is being challenged in court but remains in effect. A court has blocked enforcement of a pre-Roe ban in West Virginia while it is being challenged in court.

1. Alabama—Near-total ban

2. Arkansas—Near-total ban

3. Idaho—Near-total ban A legal challenge to this ban, which seeks to expand the exceptions allowed under the ban, is pending in federal court.

4. Kentucky—Near-total ban A legal challenge to this ban is pending in state court.

5. Louisiana—Near-total ban A legal challenge to this ban is pending in state court.

6. Mississippi—Near-total ban

7. Missouri—Near-total ban

8. Oklahoma—Near-total ban A legal challenge to this ban is pending in state court.

9. South Dakota—Near-total ban

10. Tennessee—Near-total ban

11. Texas—Near-total ban A legal challenge to this ban, which seeks to expand the exceptions, is pending in federal court.

12. West Virginia—Near-total ban A separate pre-Roe ban has been blocked from enforcement while a legal challenge is pending in state court.

States Where Abortion Is Unavailable

In two states, abortion care is unavailable even though a ban is not being enforced. Legal challenges are ongoing in both states.

13. North Dakota—Sole clinic moved to Minnesota A legal challenge to the state’s near-total ban is pending in state court, even though no abortion clinics are operating in the state.

14. Wisconsin—Clinics stopped providing abortion because the enforcement status of the state’s pre-Roe ban is unclear. A legal challenge to this ban is pending in state court.

States with Gestational Age Bans in Effect

In four states, laws prohibiting abortion after a specific point in pregnancy, which would have been unconstitutional under Roe, are in effect. These bans limit people’s ability to obtain abortion care.

15. Arizona—15-week ban A legal challenge to this ban is pending in state court.

16. Florida—15-week ban A legal challenge to this ban is pending in state court.

The legislature may take up an earlier gestational age ban in the 2023 session.

17. Georgia—Six-week ban A legal challenge to this ban is pending in state court.

18. Utah—18-week ban A near-total ban has been blocked from enforcement while a legal challenge is pending in state court.

States with Bans Currently Blocked by Courts

In three states, near-total bans or early-gestational-age bans have been blocked by state courts and are not in effect, allowing abortion services to continue for now. However, legislators in these states have demonstrated that they intend to ban abortion.

19. Indiana—A near-total ban has been blocked from enforcement while a legal challenge is pending in state court.

20. Wyoming—A near-total ban has been blocked from enforcement while a legal challenge is pending in state court.

21. Ohio—A six-week ban has been blocked from enforcement while a legal challenge is pending in state court. The legislature may take up a near-total ban in its 2023 session.

Additional States That May Ban or Restrict Abortion

In three states, anti-abortion policymakers who control the legislature and governorship have indicated that they want to ban abortion soon, but abortion care remains available for now.

22. Iowa—Earlier in 2022, the Iowa Supreme Court ruled that the state constitution no longer protects abortion rights, opening the door for a new ban.

23. Montana—After the Dobbs decision, the governor asked the Montana Supreme Court to revisit a ruling from 1999 that held the state constitution protects abortion rights. However, state courts have remained committed to protecting abortion rights over the past 23 years, even though a majority of legislators and the current governor oppose abortion rights.

24. Nebraska—In 2022, an attempt to pass a near-total ban failed in the legislature. Lawmakers may again attempt to ban abortion during the 2023 legislative session.

In two other states—Kansas and North Carolina—the legislature is hostile to abortion rights, while the governor supports access to abortion. We consider these states much less likely than the 24 other states to enact a near-total or early-gestational-age ban in the coming months.