In his old age he became more outspoken on the wrong direction that the Republican party was going in. Moving away from its libertarian roots to embrace the neofascist theological right wing.

This past election saw Goldwater vindicated in his concerns, and hopefully it will finally cause a reassessment on the right as to what damage aligning with the forces of bigotry can create in a political party.

Like the Republicans the Canadian Conservatives under Harper once gave lipservice to being libertarians, but have embraced the politics of the social conservative theocrats and authoritarian law and order types.

There are no Goldwaters in the Canadian Conservative Party anymore than there are Goldwaters left in the Republicans. Which is a damn shame.

To rephrase Lloyd Bensten's famous quote; Mr. Bush, Mr. Harper, Blogging Tories et. al I knew Barry Goldwater and you are no Barry Goldwater.

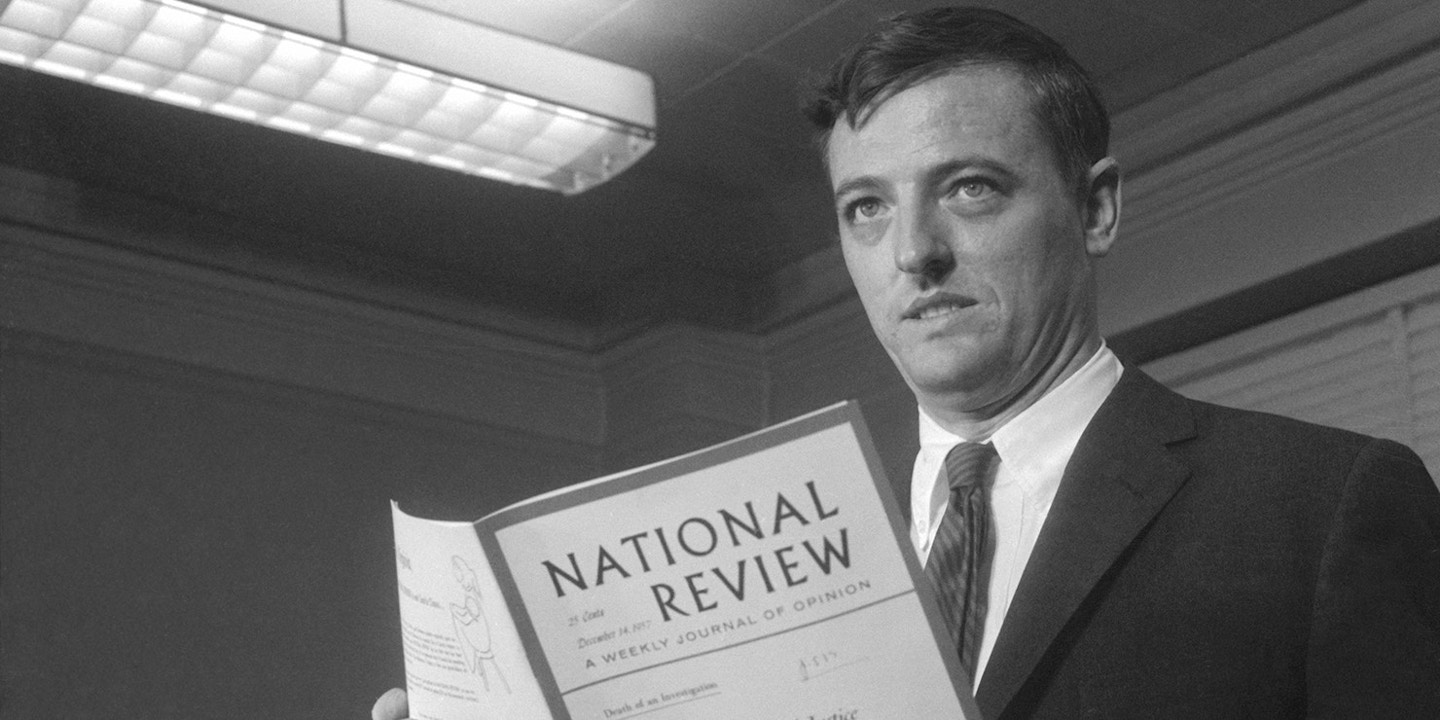

By the 1980s, with Ronald Reagan as president and the growing involvement of the religious right in conservative politics, Goldwater's libertarian views on personal issues were revealed, which he believed were an integral part of true conservativism. This put him at odds with the Reagan Administration and religious conservatives who wanted stricter government control on public and personal morality. Goldwater viewed abortion as a matter of personal choice, not intended for government intervention. In fact, his own daughter, Joanne, chose to have an abortion before her first marriage at the age of 20, and he supported her decision. He was also not against gays in the military. As a passionate defender of personal liberty, he saw the religious right's views as an encroachment on personal privacy and individual liberties. In his 1980 Senate re-election campaign, Goldwater won support from religious conservatives but in his final term voted consistently to uphold legalized abortion.Goldwater also disagreed with the Reagan administration on certain aspects of foreign policy (e.g. he opposed the decision to mine Nicaraguan harbors). Notwithstanding his prior differences with Dwight Eisenhower, Goldwater in a 1986 interview rated him the best of the seven Presidents with whom he had served.

See:

Libertarian

Death Of Laissez-Faire Politics

Fukuyama Denounces War In Iraq

A NEW AMERICAN REVOLUTION

Find blog posts, photos, events and more off-site about:

libertarian, Republican, Barry, Goldwater, President, US, Republican, elections, politics, rightwing, conservative, Mr.Conservative, Harper, Bush, Canada, abortion, Reagan, social-conservatives,

Death Of Laissez-Faire Politics

Libertarians for U.S. PresidentRon Paul Quotes Ayn Rand

Gravel and Paul on PBS