India’s Renewed Biofuels Push to Disrupt Agriculture, Worsen Inequality

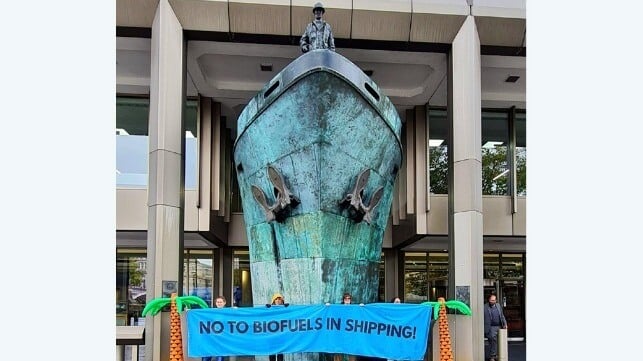

Representational Image. Image Courtesy: Flickr

One of the outcomes of the recent G20 Summit in New Delhi was the announcement of the Global Biofuels Alliance with India, Brazil, the United States and other countries taking the lead in increasing the uptake of sustainable biofuels, especially in the transport sector.

Much has been made of this initiative in India as another triumph showcasing the government’s growing global leadership and also as a step towards a big push to the country’s already sizeable and ambitious biofuels programme. The impression is that the Alliance would work towards a transition from “first generation”, or 1G biofuels, to 2G biofuels. Unfortunately, the reality is very different.

BIOFUELS

The use of biofuels, both ethanol and biodiesel, especially in transportation, is often portrayed as a major measure to move away from fossil fuel-based transport, reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and form an important intermediate step towards complete decarbonisation and renewable energy.

According to this view, biofuels have many advantages: they are derived from a renewable resource, mainly crops such as corn, sugarcane and palm oil; they use the same internal combustion engines as current automotive vehicles, which doesn’t call for major shifts in manufacturing or infrastructure; and have lower emissions than petroleum-based fuels.

Biofuels can be made in both major engine fuel variants, i.e. ethanol, as a substitute for petrol or gasoline used in internal combustion engines, and biodiesel as a substitute for diesel used in compression-ignition engines. It can also be used in various proportions of blends with their petroleum-based counterparts.

Both bioethanol and biodiesel can be used either by themselves or blended with petrol and diesel, respectively, in various proportions. Normally, ethanol-blended petrol (EBP) with up to 10% ethanol can be used in internal combustion engines without any modifications.

Whereas, EBP20 or higher, which blends with 20% or more ethanol, will require modifications or retuning of engines with higher ethanol blends requiring specially designed “flexi-fuel” engines, calling for major infrastructure investment.

Many analysts, including this writer, have questioned from the very outset both the very idea and efficacy of these biofuels, classed as “first generation”, or 1G biofuels.

Critical voices have now grown much louder, including in mainstream policy circles. Criticism has been centred chiefly on the negative impact on food security due to the use of food crops for producing automotive fuel (mostly for personal vehicles), diversion of forestland and other land-use changes away from food production, minimal, if any, cost advantage over petroleum-based fuels and only marginal or even negative reduction of GHG emissions.

Over the years, evidence of these negative aspects have mounted. Yet the push for biofuels continues, driven by continued policy support, industrial interests, especially in specific applications, and hope that technological or other developments would reverse the above trends.

NEGATIVE IMPACT OF 1G BIOFUELS

There is overwhelming evidence that 1G biofuels don’t have environmental benefits over their lifecycle.

One of the major factors is changes in land use in producing the feedstock as demand grows. Either forestland is cleared, as with palm oil in Southeast Asia, or fresh land is converted or brought under cultivation for such feedstock, such as for sugarcane in Brazil and elsewhere in South America and Africa.

These land use changes release stored carbon in the soil and pre-existing biomass, leading to a net negative in the carbon balance. Using nitrogenous fertilisers releases nitrous oxide (N2O), a GHG with 300 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide. Besides, energy is used in transporting feedstock and processing it into biofuel.

International Council for Clean Transportation estimates show that in passenger vehicles, only a 2% reduction of GHG emissions was observed with petrol blended with 5% (EBP 5) whereas biodiesel blends resulted in three times the emissions! All calculations were over the full lifecycle.

All these and other experiences from different parts of the world had resulted in a raging ‘food vs. fuel’ controversy.

It was argued that if at all crops were to be grown on cultivable land or new lands were to be brought into cultivation, food should be grown rather than crops that yielded fuel. This led to the slogan “Land for food, not for fuel”, especially for energy-guzzling personal vehicles rather than any public good.

Yet driven by market forces and a misplaced ideology that prioritised (supposedly) lower emissions over socio-economic objectives—food security, environmental sustainability and land use for the common good—the demand for 1G biofuels has grown, benefiting the land mafia and the often subsidized biofuels industry.

TOWARDS 2G BIOFUELS

Given the above negative factors, second-generation or 2G biofuels have gained considerable attention. They are differentiated from 1G biofuels by the types of materials used and the technology used to produce them.

As against 1G biofuels, based mostly on food crops, 2G biofuels are mostly made from non-food lignocellulosic materials such as agricultural wastes or residues—wheat or rice straw, sugarcane tops, corncobs, wood chips or even grasses and other such produce normally regarded as weeds or useless and could be grown on degraded or otherwise uncultivated land. Materials whose food value has already been exhausted, like municipal solid wastes or used cooking oils, are also used to make 2G biofuels.

Technologies for 2G biofuels have achieved commercial scale only within the past decade or so with mixed results. Large subsidy programmes have not taken root in the US, the European Union (EU) or other developed countries. Price fluctuations in ethanol, weak or loose mandates for biofuels, in establishing sound supply chains for feedstock such as corn cobs, etc., have all contributed to a slow uptake of 2G biofuels production.

The steady decline in diesel automobiles and the moves by numerous countries to phase out diesel-powered vehicles have left bioethanol as the main player in the game. Global trends of 2G ethanol production are fluctuating. 2G ethanol production is only around 2% of the global production of biofuels mostly in the US, EU and partially in Brazil.

Efforts have also been made over the years to lay down standards for sustainable biofuels using various criteria such as renewability, non-interference with food security, significantly lower emissions, no diversion of forest or food-crop lands, social justice and fair incomes to growers and producers, etc.

UNVIABLE 2G PLANTS

The government has given a major push to 2G bioethanol. The strategy is to initiate a 2G bioethanol programme through a special scheme for 12 new commercial-scale plants and 10 demonstration-scale plants run by public sector undertakings (PSUs) along with, if they choose, private players with competence in similar industries.

The strategy is being implemented under the new scheme with the unpronounceable and incomprehensible name of the Pradhan Mantri JI-VAN (Jaiv Indhan-Vatavaran-Anukool Fasal Awashesh Nivaran) Yojana.

Most of these plants will be located in areas with generation of large quantities of agri-waste, like rice and wheat straw, in Punjab, Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand, which will also tackle some of the severe air pollution caused in winter by stubble burning. The scheme involves substantial “viability gap funding”. or subsidy to the tune of about Rs 2,000 crore.

Clearly, the government has put the onus for such projects on PSUs—which it otherwise doesn’t support—because the plants are not profitable enough to attract private investment despite the support. In fact, even PSUs seem to be having second thoughts and, after the first few plants, have decided to go slow on starting new ones and set up 1G plants instead at about one-tenth of the cost.

An influential international study has also shown the non-viability of these plants and pointed out that in any case, 2G ethanol thus produced would only meet around 1% of the target for 2030.

Dangerously, the one plant that seems to be doing reasonably well is the PSU Numaligarh Refinery, Assam, which uses virgin bamboo as feedstock harvested from nearby land, supposedly outside the forest area. The obvious dangers of creeping diversion of forestland—once again causing more carbon debt that many years or decades of ethanol production can repay, as has happened in numerous other such projects in the Northeast, are clearly being ignored.

One way or another, land use change for production of biofuels is not environmentally sustainable.

PROBLEMATUC FALLBACK ON 1G BIOFUELS

Notwithstanding these hesitant experiments on diversification to 2G biofuels, the government has decided to double down on 1G biofuels, and has even raised the target to achieve EBP20, or 20% EBP, nationwide by 2025 instead of the earlier target of 2030.

India has come close to meeting the earlier mandated target of 10% ethanol blending albeit with great difficulty and with many changes of strategy. Use of molasses, a by-product of refined sugarcane, to make ethanol was amended to allow direct use of cane juice by citing surplus production of sugar exceeding domestic consumption.

Yet the government, mindful of sugar prices and inflation, has maintained close control on sugar exports, which have been only around 7 million tonnes (MT) against the production of around 32 MT from about 330 MT of sugarcane.

Sugarcane production is also sensitive to changes in rainfall and temperature variation, both impacted by climate change, and the quantity of surplus is always marginal. Sugarcane cultivation is also highly water-intensive and has had to be restricted in several districts. Besides, there is considerable competition from industries for potable alcohol and other chemicals, which make India a net importer of ethanol.

Despite all these difficulties, the government has further increased its bioethanol ambitions and diversified feedstock to include not just sugar but food grain such as rice and maize with loan interest subvention schemes extended to grain-based distilleries as well. The new biofuels policy goes much further than even its ambitious 2018 policy.

In the first place, we should note that the programme to achieve 5% blending of biodiesel has virtually been abandoned since production has not even reached 1% as predicted by numerous analysts right at the outset.

The new Expert Committee on Roadmap for Ethanol Blending has a new 2025 target of 13.5 billion litres of bioethanol, roughly 6.7 billion litres from sugarcane and food grains, up from 2.7 billion litres produced in 2021.

It is estimated that this will require 17 MT of food grain, compared to a mere 78,000 tonnes released in 2020-21. With the Food Corporation of India required to maintain a buffer stock of about 13 MT and the current stock being about 23 MT, which can fluctuate considerable, the margin is almost non-existent.

Can a country ranked 101 out of 116 on the World Hunger Index talk about a “surplus” that it can use for making biofuels?

Other studies have also questioned the logic of pushing for such a high biofuels target when weighed against other costs and negative impacts. The above targets will call for bringing an additional 6 million hectares (MHA) under sugarcane and around 5 MHA under maize.

According to these studies, it is senseless from an energy balance viewpoint since around 180 hectares of maize-derived ethanol would be required to annually charge an electric vehicle, which could obtain the same from a one hectare solar power plant. And all this will achieve only 5% reduction in emissions, not counting lifecycle emissions.

The renewed push for biofuels is yet another false solution to climate change and constitutes a needless diversion away from other accelerated efforts towards renewable energy, except perhaps for a very few niche areas where shifting away from petroleum will be extremely difficult, such as large aircraft and long-range diesel trucks.

For the rest, one does not need to go beyond 5% ethanol blending. If India does go down the road called for by the government, it will pay a high price in agricultural disruption, food prices and worsening inequality. Contrary to some pro-biofuel advocates, the food versus fuel debate continues to be relevant.

The writer is with the Delhi Science Forum and All India People’s Science Network. The views are personal.

LA REVUE GAUCHE - Left Comment: Search results for BIOFUEL