Claiming their rights, reclaiming identities, occupying spaces, and taking charge of their own leadership, Outlook speaks with three Dalit scholars studying abroad, who shared how caste operates in the western educational spaces and talk about their journey in a casteist society.

UPDATED: 04 MAR 2023

In September 2022, the US embassy in Delhi stated that it issued more than 82,000 student visas to Indians, a record-breaking number even surpassing that of China. However, Dalit, Adivasi, and OBC students comprise a minuscule percentage of these Indian students studying abroad.

As Seattle became the first city in the United States to ban all forms of caste-based discrimination on February 21, 2023, a global Ambedkarite movement caused ripples across India and overseas. A new generation of Dalit academicians and scholars have broken the glass ceilings and entered the western academia space, making the 'abroad return' tag no longer exclusive to the Indian upper caste and brahmins.

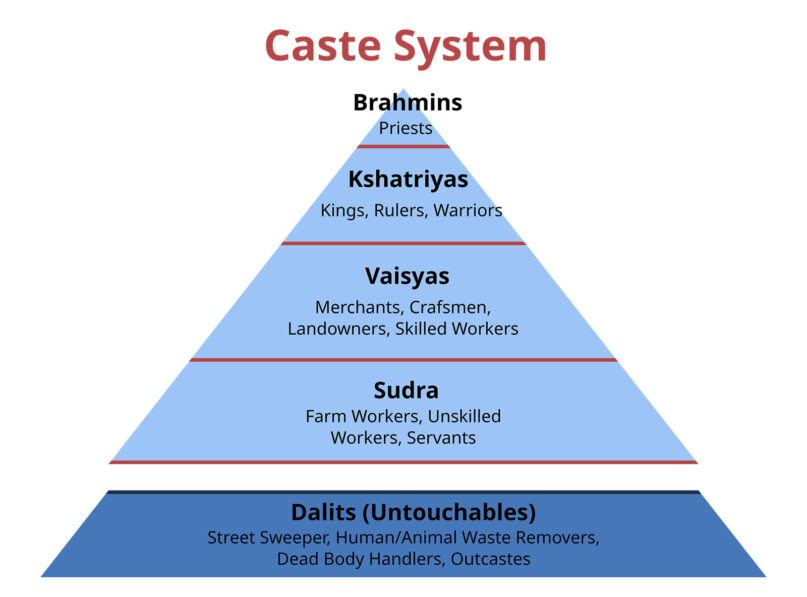

Caste and class have operated in alliance and shaped the dynamics of socio-economic-political dynamics in India. An ancient birth-based hierarchy system in India, often defended by its proponents as an occupation-based hierarchy, caste is an evil social practice, embedded in the ancient Hindu texts like Manusmriti, Vedas, Ramayana, Mahabharata, Dharma Shastra etc.

Related Stories

Inside Silicon Valley's Reports Of Casteism And Racism

Caste In The West: How Resistance, Protests And Movements Broke Silence Against Violence

Claiming their rights, reclaiming identities, occupying spaces, and taking charge of their own leadership, Outlook speaks with three Dalit scholars studying abroad, who shared how caste operates in the western educational spaces and talk about their journey in a casteist society.

A Young Dalit Feminist And A Seasoned Ambedkarite

Referring to frequent caste and sect-based battles across India in the recent past, 22-year-old Nidhi Kanaujia says that the Seattle caste discrimination ban plays a poignant role in the western context as it gives more legal visibility to the issue of caste. A student at the University of Goettingen, Germany, Kanaujia is pursuing her master's in Modern Indian Studies.

"I feel there is no mechanism in my University to address the experiences of caste discrimination, unlike India where you have redressal cells or some system into place." She, however, makes it a point to add that these systems obviously fail in their purpose in India but have largely been missing altogether in the west.

She calls herself a 'first generation learner', a young Dalit woman, who wouldn't ever dream of pursuing higher studies abroad, given her caste and class position in India, had it not been for the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Foundation Scholarship. Nidhi says that the degrees of caste discrimination in a first-world country vary from her horrific encounters in the Indian academic spaces. She shares episodes of sheer caste blindness with her fellow mates in their regular conversations, who come from upper-caste upper-class backgrounds.

Nidhi adds that a lot of students at the university and even outside are resistant to the idea of talking and discussing caste, something that does not concern or affect them. At one point, speaking of caste practices she says, "The comfort of some comes with the discomfort of many." Nidhi also highlights how students living abroad work as daily wage earners in order to support themselves, yet they would never do the same in India as their caste and class entitlement does not allow them to work as a cleaner, labourers, caregivers; etc.

Lastly, she mentions that the Centre for Modern Indian Studies in her university is currently planning to come up with certain caste guidelines, which she hopes would prove effective in combatting caste discrimination.

Academician and a student at the Teachers' College (TC) at Columbia University, Vikas Tatad is the only Dalit student in his school which comprises around 7,000 students including around 40 to 50 per cent of South and East Asian students. "When I first came to the university, I looked for Dalit Adivasi and OBC students, only to find that there were none at TC," Tatad says. He feels no sense of belongingness with his fellow Asians and Indians who celebrate Holi, Diwali, and other popular Hindu festivals but take no cognizance of Ambedkar Jayanti, a day that marks the foundation of Dalit and non-Savarna pride. "We the rejected people of India was a movement that began with Ambedkar who will continue to stay relevant for another thousand years."

Caste is not "our" problem but that of the Brahmins and the UCs (Upper Castes), he says emphasizing that it is time that the non-Savarnas should now be in power. Tatad was elected the chairperson for the University Policy and Rules Committee which recently was asked to formulate and review a policy on harassment and discrimination. "There were multiple categories enlisted in the policy but caste." Upon his suggestion, two days ago, the committee is in the process to adopt caste as a protected category.

Tatad does not mince his words when he talks about Indians who have migrated abroad and carry their caste identities with them. The young scholar, whose journey entails from the slums of Siddharthnagar in Amravati to Columbia University, also the alma mater of his ideal, Ambedkar, calls the upper caste Indian diaspora in the US and abroad protesting against the Seattle Caste discrimination ban a "sick" lot. "They can only be cured with the medicine of Ambedkar's ideals," he says. For him, Ambedkar is a humanist, liberal, and democrat whose position must be advanced internationally as an academician, responsible for the conscious liberation of the marginalized.

Caste And Queerness

Based in Germany at present, Aroh Akunth is a Dalit transfeminine writer-performer and student at the Centre for Modern Indian Studies at the University of Göttingen. Speaking with Outlook, Aroh says that India constitutes around 17 per cent of the world population, while the Dalits are about 17-20 per cent of the Indian population, which makes the Dalits one of the world's largest segregated populations. However, the recognition of this aspect is bleak and the reparations are slow.

The politics of caste is entrenched in the politics of identities, associated with one's birth and essentialism of it. In sense of the 'intersectionality' of caste and queer identities in academic disciplines and pedagogy, Aroh observes that the possibilities it brings are yet to be explored and are very much based on what a lot of Dalit activists have already done. "It's going to be exciting to change the way we see the world and experience it."

Acknowledging that the scope of caste and queerness, through the Dalit queer lens, is quite unexplored and unlimited as far as its potential is concerned. They believe that the mainstream academic spaces in some time will begin to operate from the perspective of critical caste studies. Aroh also notes that, unlike the critical race theory, critical caste studies are still developing. They also added that this late development is the possible result of where it is located and because of how cruel probably the system is, hence taking much more time to be addressed.

"But there is hope in the western academia that once political caste studies take the centre stage, especially in studies dealing with South Asia or the human condition. This will give us a better engagement, or better shift in academia, which is how one can tell the academia has progressed so far," Aroh says.

The Seattle City Council in Washington state of the United States became the first in the country last month to specifically ban caste-based discrimination. Here is all you need to know about the law.

UPDATED: 03 MAR 2023

Last month, Seattle became the first city in the United States to ban caste discrimination.

The Seattle City Council passed an ordinance by a vote of 6:1. After the vote, caste became one of the categories along with others like race and gender which cannot be the basis of discrimination in Seattle city in Washington state of the United States.

Caste is a social system in which people are put into a social hierarchy on the basis of their birth. Certain castes classified as lower have been historically marginalised and discriminated against in the caste system. The caste system traces its roots to South Asia and has reached the West with migration.

Related Stories

What Does Seattle Caste Discrimination Ban Mean For India?

Seattle Caste Discrimination Ban An 'Extraordinarily Historic Victory' Of Oppressed Castes: Kshama Sawant

Here we explain what the Seattle law is, why the law was made, and what led to its making.

What’s the Seattle caste discrimination law?

The Seattle City Council passed an ordinance banning caste discrimination in the city on February 21. The law includes caste in the list of protected categories, which refer to the grounds on which persons cannot be discriminated against in Seattle.

The law addresses caste discrimination in workplaces and public spaces such as in housing and transportation sectors, as per a statement by Kshama Sawant, the Seattle Councilmember behind the law.

“The legislation will prohibit businesses from discriminating based on caste with respect to hiring, tenure, promotion, workplace conditions, or wages. It will ban discrimination based on caste in places of public accommodation, such as hotels, public transportation, public restrooms, or retail establishments. The law will also prohibit housing discrimination based on caste in rental housing leases, property sales, and mortgage loans,” said Sawant in a statement before the bill was passed into law.

The law also gives a formal definition of caste. The law defines caste as “a system of rigid social stratification characterized by hereditary status, endogamy, and social barriers sanctioned by custom, law, or religion”, according to a document on the Seattle Council’s website.

Besides making caste a protected category in Seattle, the law also makes provision for sensitivity training and outreach programs that are aimed towards increasing awareness of caste discrimination with the idea of preventing it. The law also makes provisions for recruiting consultants to train the Council’s staff.

“To prevent discrimination, appropriate communication and education about the new protected class are important. Appropriate media and public information regarding caste discrimination will increase public support, and compliance, and will inform the public of their rights regarding this new law…We want to ensure that community members – and business

owners in particular — are adequately informed and provided the education to prevent possible law violations,” said a memo circulated by a Council official.

While making a case for further allocation of resources for the implementation of the law, the Council official in the memo said that without education, they would be bogged down by investigation instead of carrying out prevention.

“Without adequate resources, businesses will not be aware of this new protection. As the law requires, we will investigate every claim of discrimination we receive. However, since prevention through education, training and outreach would not be possible, we may incur an increase in investigation cases resulting in longer case processing times,” said the memo.

What’s the idea behind the Seattle caste ban law?

Even though caste discrimination has roots in South Asia, it has been exported to the West with the large diaspora and persons of South Asian heritage there.

There are around 5.4 million South Asians in the United States, according to the group South Asian Americans Leading Together. At around 4 million, Indian Americans are the second-largest ethnic minority in the United States. In such conditions, the issues plaguing the Indian and South Asian societies are bound to be carried to the United States.

The Seattle law acknowledges caste discrimination in Seattle and elsewhere. Council member Sawant has also spoken about the prevalent caste discrimination in the United States.

“With over 167,000 people from South Asia living in Washington, largely concentrated in the Greater Seattle area, the region must address caste discrimination, and not allow it to remain invisible and unaddressed…Caste discrimination doesn’t only take place in other countries. It is faced by South Asian American and other immigrant working people in their workplaces, including in the tech sector, in Seattle and in cities around the country,” said Sawant in a statement.

Explaining the uniqueness of caste discrimination, a legislative document notes, “Unlike some other groups subject to oppression from dominant identities where the marginalised identity is clear from visible markers (ie. race or gender), caste does not have visible markers (analogous to sexual orientation), so exposing discrimination may require self-identification that can itself expose those individuals to further discrimination.”

Another document noted that the existing legal or anti-discrimination provisions might not cover caste discrimination.

“Lower caste individuals and communities can suffer discrimination based on their caste identity, and it is not clear that existing protections against discrimination based on characteristics like race, religion, national origin, or ancestry are sufficient…This legislation will allow those subject to discrimination on the basis of caste a legal avenue to pursue a remedy against alleged discrimination,” said the document.

The force behind the Seattle law

While the main driver behind the Seattle caste discrimination law was Councilmember Sawant, a number of organisations working in the field of Dalit and minority rights were also included in the making and promotion of the bill made into law last month.

Sawant described the Seattle caste discrimination law as an “extraordinarily historic victory” of the oppressed castes across the world. She is an Indian-American economist and a socialist politician. She is 49.

Sawant migrated to the United States in the late 1990s. Her profile on the Seattle Council's website notes she is part of the international socialist movement.

Sawant alleged to PTI that caste discrimination is prevalent in some of the major tech giants.

Sawant told PTI that she was able to achieve this historic feat despite tough opposition mounted by a group of Indian-Americans, whom she described as “right-wing Hindus”, resistance from the tech companies, and almost no cooperation from the Democrats.

She said, “So this is an absolutely earth-shattering victory because this is the first time outside South Asia that the law has decided that caste discrimination is not going to be invisible eyes, but instead it's going to be codified in the law that it is illegal.”

Organisations such as Equality Labs, Ambedkar International Center, and Ambedkar King Study Circle, were part of the drafting process. Equity Labs noted that several organisations like the Indian American Muslim Council, National Academic Coalition for Caste Equity, and Ravidassia and Sikh gurdwaras from throughout the Northwest USA helped bring the law.

“The ratification of the ordinance to ban caste-based discrimination in Seattle is a first in history and a culmination of years of Dalit feminist research and organizing that has broken the silence about caste oppression in our communities. We have finally found ways to initiate healing from this violent caste system in our diasporic networks and in our homelands — through the protection of this powerful ordinance,” noted Equity Labs in a statement.