Retirement of coal-fired power plants in the West has done nothing to reverse global coal demand.

Global coal consumption is set to remain at these high levels—or even hit new all-time highs—for a few more years.

Global operating coal power capacity has increased by 13% since 2015, data from Global Energy Monitor shows.

Developed economies have been reducing their use of coal in recent years, but the world isn’t ready to kick its coal addiction, not yet. Developing markets in Asia are boosting their coal-fired power generation to meet surging electricity demand.

Despite continued retirements of coal-fired power in the U.S., lower coal demand in Europe, and the end of the 142-year coal electricity in the UK, global coal demand hit another record high last year. And consumption is set to remain at these high levels—or even hit new all-time highs—for a few more years.

Emerging Asian economies, led by China and India, have been sustaining global coal demand growth this decade. They plan additional coal-fired capacity to support their respective renewables booms with 24/7 baseload power and avoid power crunches or blackouts like the ones they suffered in the early 2020s.

Global Coal Demand At Record High

Global operating coal power capacity has increased by 13% since 2015, data from Global Energy Monitor (GEM) shows. Since 2015, when the countries reached a deal on the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the world has added 259 GW of operating coal power capacity. As of the end of 2024, total operating coal power capacity hit a record high of 2,175 gigawatts (GW), while another 611 GW of capacity was under development, according to GEM’s Global Coal Plant Tracker.

Global coal demand surged to another record high in 2024, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said in December, expecting the world’s coal consumption to level off through 2027.

The previous record was from a year earlier. In 2023, demand hit the then-record, and the IEA then predicted flat consumption in 2024. They were wrong—demand increased last year, their own analysis showed.

Despite forecasts of plateauing, global coal consumption could continue to rise this year and the next few years, too, depending on how China’s economy and energy security policies evolve in the coming months.

A plateau in global coal demand will largely depend on China, the IEA noted in December.

“Weather factors – particularly in China, the world’s largest coal consumer – will have a major impact on short-term trends for coal demand. The speed at which electricity demand grows will also be very important over the medium term,” said IEA Director of Energy Markets and Security Keisuke Sadamori.

Electricity demand globally is set to jump in the coming years with AI advancements and data center investments.

Growth in power demand in 2024 and 2025 is forecast to be among the highest levels in the past two decades, the IEA said in the middle of 2024.

The surge in electricity consumption could slow coal retirements in developed economies and further raise coal demand in emerging markets in Asia, especially if the growth in renewable energy capacity is not enough to meet the rise in power demand.

Two Worlds of Coal Consumption

While solar power will continue to drive the growth of U.S. power generation over the next two years, coal power output will remain unchanged at around 640 billion kilowatt hours (kWh) in 2025 and 2026, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) said last month. America’s coal electricity generation was 647 billion kWh in 2024.

U.S. coal retirements are set to accelerate this year, removing 6%, or 11 GW, of coal-generating capacity from the U.S. electricity sector. Another 2%, or 4 GW, of coal capacity would be removed in 2026, the EIA forecasts. Last year, coal retirements represented about 3 GW of electric power capacity removed from the power system, which was the lowest annual amount of coal capacity retired since 2011.

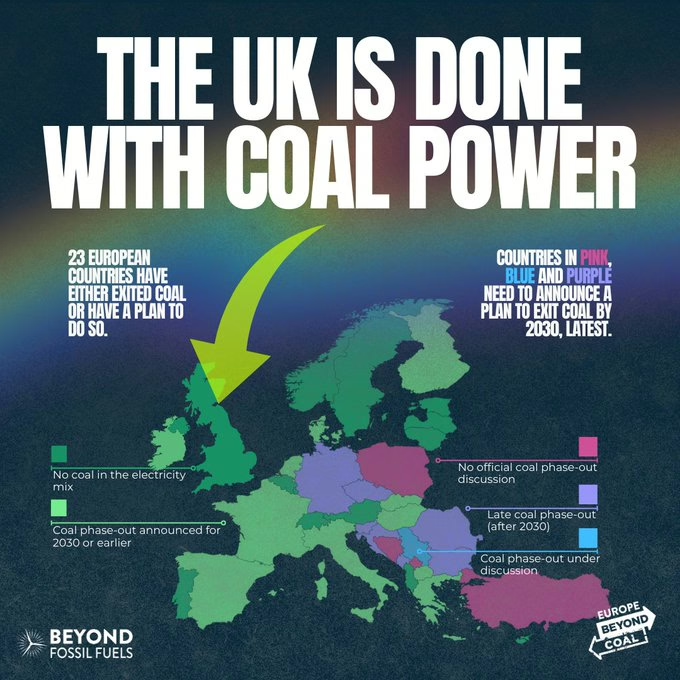

Across the Atlantic, last year saw a monumental moment in Britain’s electricity system with the switching-off of the last remaining coal power plant in the country. The plant at Ratcliffe-on-Soar was shut at the end of September, ending 142 years of coal-fired electricity generation in the UK and making Britain the first G7 country to phase out coal.

In the European Union, solar power overtook coal generation in 2024, with solar accounting for 11% of EU electricity and coal falling below 10% for the first time ever, data from clean energy think tank Ember showed.

But in China and India, the world’s biggest and second-biggest coal users, respectively, coal is still king despite the surge in renewable power installations.

China’s thermal power generation, which is overwhelmingly dominated by coal, rose by 1.5% in 2024 from a year earlier to a record high of 6.34 trillion kWh, as coal consumption in the electricity sector continues to grow, and so are China’s production and imports.

This year, China’s coal demand and production are expected to continue rising, and the fuel is set to remain the backbone of the country’s energy system, according to China Coal Transportation and Distribution Association.

In India, coal use is also rising -- demand increased in 2024 by more than 5% to hit 1.3 billion tons—a level that only China has reached previously, per IEA data.

India has reduced coal imports, but that’s only because it aims to hike domestic output to source more coal at home. With industry expected to expand and power demand to soar, India is set to use more of its lower-quality domestic coal to meet its consumption needs.

By Tsvetana Paraskova for Oilprice.com

The United States remains a major consumer and producer of coal, even with the growth of renewable energy sources.

Coal consumption and production have decreased in recent years, but coal still plays a significant role in U.S. electricity generation.

Changes in political administration and international energy demand could influence the future of coal in the United States.

While many countries worldwide are moving away from a dependence on coal, the U.S. still relies heavily on the dirtiest fossil fuel for its power. The U.S. has experienced an accelerated green transition since the introduction of the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022, which has spurred a massive increase in the country’s renewable energy capacity and attracted billions in private funding.

However, this shift has not stopped the U.S. reliance on coal, as the third-largest consumer of coal in the world after China and India. The U.S. continues to be the fourth-largest producer of coal, after China, India and Indonesia, and it has more coal reserves than any other country. The U.S. had 206 active coal plants remaining in 2023. Around a quarter of domestic coal generation is expected to be retired by 2040 but the pace of planned retirements slowed last year as energy demand increased.

Coal production in the U.S. has fallen in recent years, as oil and gas production increased, and the country expanded its renewable energy capacity. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), U.S. coal production decreased 2.7 percent year over year from 2022 to 2023, to 577.9 million short tons (MMst). Meanwhile, U.S. coal consumption fell by 17.4 percent in this period, from 515.5 MMst to 425.9 MMst, and the electric power sector contributed 387.2 MMst (90.9 percent) of total U.S. coal consumption in 2023.

The EIA forecast that coal’s share of U.S. electricity generation would fall to a record low of 16.1 percent in 2024, as several coal mines were retired and alternative energy capacity increased. Non-coal power generation was expected to be sourced from natural gas, 41.6 percent; nuclear, 19 percent; and renewable energy sources, 22.8 percent. The EIA expected coal production in 2024 to total 499 MMst, marking a decrease of 14.2 percent from 2023, and fall by a further 5 percent in 2025, to 474 MMst. It forecast that the electricity power sector would consume 384 MMst in 2024, around 1 percent less than in 2023, and an additional 2 percent less in 2025.

However, as coal production begins to decrease faster than consumption, it will likely lead to a reliance on existing inventories, until the alternative energy capacity increases. Coal inventories stood at 120 MMst by the end of July last year and are expected to fall to around 84 MMst by the end of 2025.

In terms of exports, the EIA expected coal exports to total 103 MMst in 2024, marking a 3 percent increase on 2023. This figure is expected to climb by an additional 0.8 percent in 2025, to 103.8 MMst. The EIA stated, “Although coal exports in our forecast remain robust, ongoing declines in coal production are the result of less coal being used to generate electric power domestically due to relatively low natural gas prices and 12 GW of coal-fired electricity generating capacity going into retirement.”

In addition to heavy domestic reliance on coal, an increase in coal consumption in Asia could drive growth in the U.S. coal export market. In 2024, India’s thermal coal imports rose by around 12 percent, while China’s rose by 8 percent, a trend which is expected to continue for several years. The IEA predicted in 2024 that by 2035, global electricity demand would be 6 percent higher than it had previously predicted, leading to a prolonged reliance on coal to meet this demand.

While U.S. domestic coal use and production has fallen in recent years, under the new President Donald Trump administration, we could see this downward trend shift in a different direction. On his first day in office, Trump declared a national energy emergency, followed shortly after by the announcement that coal could be a fuel source for new electric generating plants. During a virtual appearance at the annual World Economic Forum in Davos, Trump stated, “They can fuel it with anything they want, and they may have coal as a backup — good, clean coal.” He added, “We have more coal than anybody.” Following Trump’s comments, U.S. coal producers’ shares climbed. The largest U.S. coal miner, Peabody Energy Corp., saw its shares increase by around 7.6 percent.

Despite Trump’s support for coal as a ‘backup’ energy source, U.S. efforts to ramp up oil and gas output mean that natural gas is now cheaper, and coal is no longer economically viable in comparison. While coal might be phased out at a slower pace under Trump, most experts agree that coal is simply too expensive to make a meaningful comeback. While the increasing power demand will drive energy production, this demand will likely be met with higher gas output, as well as through the expansion of the country’s renewable energy capacity.

By Haley Zaremba for Oilprice.com

Bloomberg News | February 12, 2025 |

A coal-fired power station in Nantong, China.

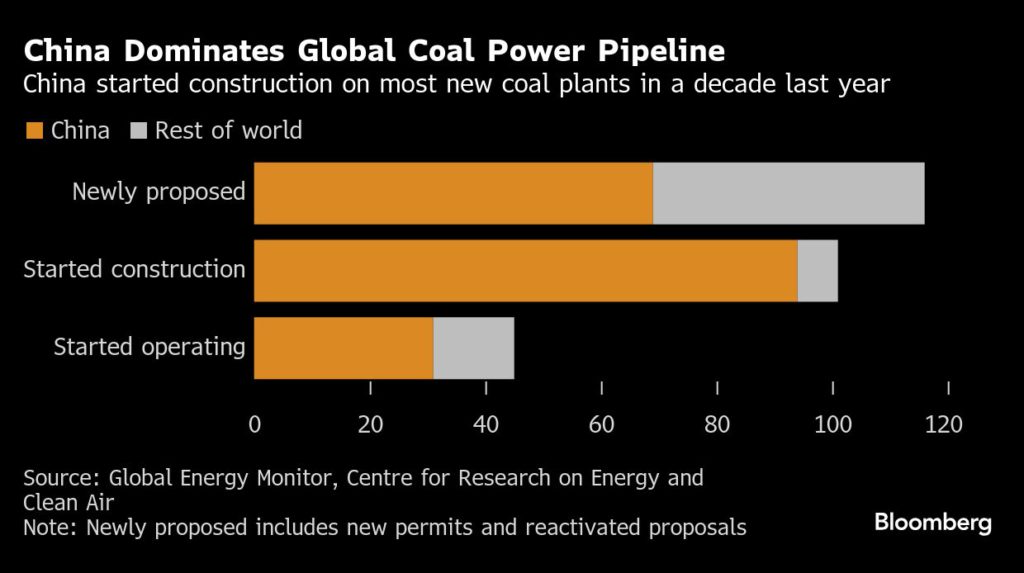

China embarked last year on its biggest coal-power building boom in a decade, reinforcing the role of the dirtiest fossil fuel in its energy mix even as it aims to transition to renewables.

Nearly 95 gigawatts of new coal-fired generators started construction, the most since 2015, according to a joint study released on Thursday by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air and Global Energy Monitor. Local governments also sped up permits for future plants toward the end of the year after a slowdown in the first half, approving a total of 67 gigawatts of new capacity in 2024.

The surge coincides with the country’s breakneck development of clean energy, which included 356 gigawatts of new wind and solar capacity in 2024, making additional electricity from fossil fuels unnecessary. Thermal power generation grew less than 2% last year, and President Xi Jinping has pledged to reduce coal use from 2026.

Still, the fuel is regarded as a key pillar of energy security, and China’s planners have said it’s still needed as a backup to balance out the intermittent electricity provided by wind and solar. But there are signs, including a rise in curtailments of clean energy, that coal generators are entrenching their position and crowding out renewables, limiting the country’s ability to peak emissions before Xi’s 2030 deadline, according to the report.

Coal producers are helping to push the continued growth of the fleet, with more than three-quarters of new permits going to companies with mining operations, the report said. Long-term coal-power contracts are also reinforcing the fuel’s dominance at the expense of renewables.

“China’s rapid expansion of renewable energy has the potential to reshape its power system, but this opportunity is being undermined by the simultaneous large-scale expansion of coal power,” said Qi Qin, an analyst at CREA.

Global coal demand continues to hit record highs.

China and India are the biggest consumers and the key growth drivers of rising coal demand.

In Vietnam, operating coal power capacity has doubled over the past decade.

Global coal demand continues to hit record highs despite the boom of renewable energy installations, including in the most coal-dependent regions in Asia.

China and India are the biggest consumers and the key growth drivers of rising coal demand, but other emerging markets in south and Southeast Asia are also propping up coal use.

One of these is Vietnam. In recent years, soaring industrial activity and economic growth well above the global average have made Vietnam a power-hungry, predominantly manufacturing economy. The country has become a solar power leader among the countries in Southeast Asia, but it continues to rely on thermal coal for industry and is one of the few countries worldwide building new coal-fired power capacity.

Global coal demand surged to another record high in 2024, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said in December, expecting the world’s coal consumption to level off through 2027.

Meanwhile, global operating coal power capacity has increased by 13% since 2015, data from Global Energy Monitor (GEM) shows. Since 2015, when the countries reached a deal on the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the world has added a total of 259 GW of operating coal power capacity. As of the end of 2024, total operating coal power capacity hit a record high of 2,175 GW, while another 611 GW of capacity was under development, according to GEM’s Global Coal Plant Tracker.

In Vietnam, operating coal power capacity has doubled over the past decade, the data showed. The country has added 14 GW of coal power capacity since 2015 and had a total of 27.2 GW capacity as of the end of 2024. Moreover, Vietnam has another 4.7 GW of coal capacity under development, according to the GEM data.

The manufacturing boom and the resulting surge in coal power demand have also pushed Vietnam’s coal imports to a record high.

Last year, the Southeast Asian country’s thermal coal imports jumped by 31% to a record 44 million metric tons, according to data by Kpler cited by Reuters market analyst Gavin Maguire.

Vietnam’s import growth far exceeded the global increase of 1% and the 11% rise in coal imports in China, the top coal consumer and importer.

Despite a surge in solar PV installations in recent years, fossil fuels – predominantly coal – account for more than half of the country’s electricity generation, data from clean energy think tank Ember showed.

More than 42% of the power generation came from clean energy sources, most of all hydropower, whose share is about 30% of all electricity supply.

Vietnam leads regional peers such as Thailand and the Philippines in terms of solar and wind growth. But as power demand more than doubled over the past decade, Vietnam met this jump with a doubling of coal generation, which led to a tripling of emissions, Ember said.

Coal will continue to be a pillar of Vietnam’s power generation as its economy and industry continue to expand at rates above the global average.

Stronger exports of manufactured goods helped Vietnam’s economy to accelerate in 2024 and grow by 7%, up from the 5% economic growth seen in 2023.

Key to industry growth was the increase in coal imports as the Communist-led country looked to avoid power crunches and shortages.

Vietnam is set to continue outperforming regional peers in economic growth this year, Oxford Economics said in a December forecast.

Vietnam itself has just said that it would officially revise up its GDP growth target for 2025 to 8.0% from 6.5%-7.0%.

The strong economic growth in Vietnam and the rising coal dependence of Indonesia and the Philippines make Southeast Asia a driver of global coal demand growth, although not at the scale of China and India.

By Tsvetana Paraskova for Oilprice.com