Barmen, 1913. Photo: Public Domain

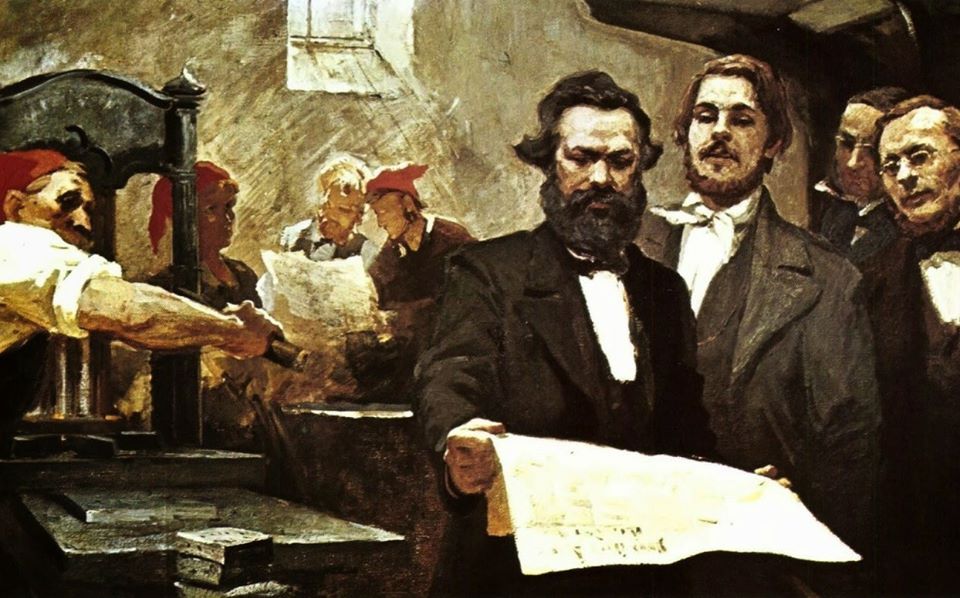

Barmen, 1913. Photo: Public Domain Dialectics of Nature, Friedrich Engels

Dialectics of Nature, Friedrich Engels

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Barmen, 1913. Photo: Public Domain

Barmen, 1913. Photo: Public Domain Dialectics of Nature, Friedrich Engels

Dialectics of Nature, Friedrich Engels

[Editor’s note: This is a slightly edited and updated version, including several missing footnotes, of an article that was first published on LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal in 2007. The original version can still be found here.]

The theory of the labour aristocracy argues that opportunism in the working class has a material basis. The superprofits of monopoly capital support the benefits of a stratum of relatively privileged workers, whose interests in this are expressed by class-collaborationist politics. Karl Marx and, especially, Friedrich Engels, first developed this theory. It is most closely associated with Vladimir Lenin, however, for whom it became “the pivot of the tactics in the labour movement that are dictated by the objective conditions of the imperialist era.”1

Many revolutionaries who claim Lenin as an influence nevertheless reject the theory. They deny the character of imperialism as monopoly capitalism, the existence of the labour aristocracy or the stability of opportunism. Their method mimics the empiricism of bourgeois economics, political science and sociology rather than following Marx and Engels’ injunction to study history. Their acceptance of the results of this reflects the very often dominant position of opportunism in the working-class movement.

This article considers the scope and significance of the theory and its application by Engels to understanding the politics of the English working class in the latter half of the nineteenth century. A second article will discuss Lenin’s development of the theory (using principally German and US historical examples); the strategies and tactics he proposed and controversies surrounding the theory about the source and nature of the “bribe” to the labour aristocracy; the stratum’s composition; and the relationship of the labour aristocracy to the labour bureaucracy and the rest of the class. The final article in the series will apply the theory of the labour aristocracy to an understanding of the history of the Australian working class.

In 1913, Lenin asked how the Australian Labor Party, as the workers’ representatives, could predominate in parliament “and yet the capitalist system is in no danger?” His answer was that the ongoing formation of Australia as an independent capitalist state and the formation of the Australian working class by the migration of liberal British workers determined the liberal-bourgeois character of the ALP. The party concerned itself with what elsewhere had been done by parties representing liberal capitalists:

Naturally, when Australia is finally developed and consolidated as an independent capitalist state, the condition of the workers will change, as also will the liberal Labour Party, which will make way for a socialist workers’ party … The rule is: a socialist workers’ party in a capitalist country. The exception is: a liberal Labour Party which arises only for a short time by virtue of specific conditions that are abnormal for capitalism in general.2

When most of the parties of the Socialist International supported their own states in World War I, however, Lenin changed his view about the rule. “Certain groups of workers have already drifted away to opportunism”,3 he noted, “sacrificing the fundamental interests of the masses to the temporary interests of an insignificant minority of the workers or, in other words, an alliance between a section of the workers and the bourgeoisie, directed against the mass of the proletariat”4 through “class collaboration, repudiation of the dictatorship of the proletariat, repudiation of revolutionary action, unconditional acceptance of bourgeois legality, confidence in the bourgeoisie and lack of confidence in the proletariat.”5 He argued:

… economically, the desertion of a stratum of the labour aristocracy to the bourgeoisie has matured and become an accomplished fact; and this economic fact, this shift in class relations, will find political form, in one shape or another, without any particular “difficulty” … a “bourgeois labour party” is inevitable and typical in all imperialist countries … unless a determined and relentless struggle is waged all along the line against these parties — or groups, trends, etc., it is all the same — there can be no question of a struggle against imperialism, or of Marxism, or of a socialist labour movement.6

Lenin considered that “opportunism was engendered in the course of decades by the special features in the period of the development of capitalism, when the comparatively peaceful and cultured life of a stratum of privileged workingmen ‘bourgeoisified’ them.”7 It developed, he noted elsewhere, “between 1871 and 1914 … first as a mood, then as a trend, and finally [forming] a group or stratum among the labour bureaucracy and petty-bourgeois fellow-travellers.”8 With the start of the war, opportunism matured, in the form of social-chauvinism “to such a degree that the continued existence of this bourgeois abscess within the socialist parties has become impossible.”9 For revolutionaries, in reality, this meant “a split with the social-chauvinists was inevitable” because of the “most profound connection, the economic connection, between the imperialist bourgeoisie and the opportunism which has triumphed (for long?) in the labour movement.”10

Lenin’s key collaborator at the time, Grigory Zinoviev, in a survey of the social roots of opportunism, cited Australia only as an exceptional example of the relationship between the labour aristocracy and its leadership in the labour bureaucracy, and class collaboration:

The reactionary role of the “socialist bureaucracy” appears nowhere so ostentatiously as in Australia, that veritable promised land of social reformism … the Australian labour movement has been a constant prey of leaders on the make for careers. Upon the backs of the labouring masses there arise, one after another, little bands of aristocrats of labour, from the midst of which the future labour ministers spring forth, ready to do loyal service to the bourgeoisie. All these Holmans, Cooks and Fishers were once workers. They act the part of workers even now. But in reality they are only agents of the financial plutocracy in the camp of the workers.

The caste of the “leaders” here appears quite openly as a unique type of jobs trust for functionaries …These “leaders” have proved to be the worst sort of chauvinists. The majority of the workers pronounced themselves against the introduction of conscription in Australia. But Fisher and his friends continue to represent the views of the bourgeoisie.11

Lenin’s formulation was and remains provocative. It was a theoretical foundation for the formation of the Third International and its Communist parties. Even among the revolutionary left, however, many have subsequently rejected it either wholesale, as divisive in the labour movement or referring to a historical curiosity, or so much of it that any remnant of the labour aristocracy must be insignificant. The theory that the social basis of opportunism was and is found in a relatively privileged stratum of the working class — the labour aristocracy — is controversial because it partly contradicts other elements of the discussion in historical materialism about the dynamics of working-class radicalisation and because of the political conclusions that flow from it about the strategy and tactics to fight opportunism.

The starting point of the historical materialist discussion of working-class politics and class consciousness is the material determination of ideas and especially “the conditioning of social, political and intellectual life processes in general” by the mode of production of material life. Working-class radicalisation must, therefore, “be explained … from the contradictions of material life, from the existing conflict between the social productive forces and the relations of production”, such as the fettering of the productive forces and the class antagonism and social crises of mature capitalism.12 The history of the working-class movement, however, denies all argument that revolutionary class consciousness among workers develops in lockstep with the intensification of the fundamental contradictions of the capitalist mode of production.

Much of the discussion has been concerned with explaining the separation of economic and political struggles in the working-class movement, which results in the working class not spontaneously confronting capital’s political power, concentrated in the state, and with the means for overcoming this separation.

In this discussion, “alien” social elements in the working class and its movement — workers with petty-bourgeois backgrounds or the desire to enter the ranks of the petty bourgeoisie, or intellectuals attracted to the workers' movement,13 and occupational, sexual, racial, ethnic, national, religious or other divisions — have been proposed as important barriers to the development of working-class unity in opposition to capitalism. Bourgeois ideological influence has also emerged in the discussion as a key concern, whether this has been understood to result from: the capitalist domination of the means of ideological dissemination; the structural separation in capitalism of a sphere of political and juridical equality from that of capitalist exploitation in the productive sphere;14 or workers’ experience as sellers of labour-power, which confines their perspective, through commodity fetishism, of their social relations to capitalists to that of equal or unfair exchanges of wages for labour-power, and their organisations to their sectional origins and ongoing operation within the capitalist system.

The focus of the response to these conditions of division and bourgeois ideological influence in the working class has been the view that the working class must, in order to conquer political power, carry out a social revolution and ultimately abolish classes, form a political party of its own. This strategic concept was already formulated and acted upon in the nineteenth century. It became more defined, reflecting an understanding of the impact of these conditions, however, on the basis of the experience of the Russian revolutionary movement in the first two decades of the twentieth century:

The party, in order to express the proletariat’s hegemonic aim of overthrowing capitalism, must organise, principally, revolutionaries, rather than the class as a whole.

The party needs to carry out the broadest possible political work (not restricted, for example, by the boundaries of legality). Workers’ political class consciousness involves understanding the relationships between all the various classes and strata of modern society and acting as a revolutionary socialist with regard to these. Therefore, its acquisition, through the experience of struggle, cannot occur in the sphere of relations between employers and workers alone.

The perspective of a party as the leadership of the working class, with a consciousness different from that arising spontaneously among workers, posed anew the problem of how working people can develop as revolutionaries and as a mass revolutionary movement. The solutions offered included: persistent effort to educate and train politically active workers as revolutionaries without them losing contact with their fellow workers; the role of a revolutionary situation and its resultant mass action, such as strike waves, in opening the way for the party to connect closely with a movement of the mass of the population; and the capacity of the party to reshape its theory and pose its slogans and demands so that these broader masses can see from their own experience that the political strategy and tactics of the party are correct.

This perspective, however, still considers that all parts of the working class can become revolutionary.15 The political activity of the more advanced workers is different from the rest of the class only because it is “all-sided and all-embracing political agitation … work that brings closer and merges into a single whole the elemental destructive force of the masses and the conscious destructive force of the organisation of revolutionaries.”16

Lenin argued that capitalism would necessarily find support within the labour aristocracy, however. Considering the question whether some of the opportunists could return to revolutionary socialism, he responded: “This is possible, but it is an insignificant difference in degree, if the question is regarded from its political, i.e., its mass aspect.” His theory was not concerned with the consciousnesses of individual workers from the labour aristocracy, but with how, historically, an influential part of the workers from it had reached settlements with “their” capitalists.17 He continued: “The social chauvinist or (what is the same thing) opportunist trend can neither disappear nor ‘return’ to the revolutionary proletariat … There is not the slightest reason for thinking that these parties will disappear before the social revolution.”18

Thus there are two political trends in the working class, pitted against each other in a process of struggle: the opportunist, an alliance of parts of the class with the bourgeoisie which is underpinned by the relative privileges of the labour aristocracy; and the revolutionary, rooted in the elements of the class emerging as its spontaneous movement, the starting point for the development of revolutionary consciousness.19 Lenin wrote: “In the epoch of imperialism, the proletariat has split into two international camps, one of which has been corrupted by the crumbs that fall from the table of the dominant-nation bourgeoisie.”20

Tony Cliff, in his 1957 article “Economic Roots of Reformism”, rejected Lenin’s theory, claiming it means “a small thin crust of conservatism hides the revolutionary urges of the mass of the workers.”21 He stated that, instead, in the advanced capitalist countries “reformism, a belief in the possibility of major improvement in conditions under capitalism”, had been solid and “spread throughout the working class, frustrating and largely isolating all revolutionary minorities” for the previous half century. Reformism, he said, “reflects the immediate, day-to-day, narrow, national interests of the whole of the working class in Western capitalist countries under conditions of general economic prosperity”, which include imperialist access to colonial markets. He expected the eventual withering away of this prosperity, which, he said, had already been seriously undermined in the 1930s, before it had gained a new lease of life through the imperialists’ war economy. With the removal of the foundation of reformism, which at the same time would end the basis on which the reformist labour bureaucracy could effectively discipline the working class (“the extent [to which] the economic conditions of the workers themselves are tolerable”), only the idea would linger on. He said this could then be overthrown by the conscious revolutionary action of socialists, whose main task, facilitated by sharpening social contradictions, is to “unite and generalise the lessons drawn from the day-to-day struggle.”

The period Cliff discussed, however, included both times of capitalist prosperity, with relatively high employment levels and rising living standards for workers, which were the expansionary phases of long waves of capitalist development that began at the end of the nineteenth century and soon after World War II, and the period of social crisis and stagnation spanning the two world wars and the Great Depression.22 In this last period, then, capitalism’s contradictions and social antagonisms intensified, spurring the spontaneous element of the proletarian movement. Workers came into struggle regardless of their previous consciousness. Consequently, reformism was not solid in the sense suggested in Cliff’s argument; that is, that the spontaneous movement was insufficient for a successful party intervention. Moreover, on this basis revolutionary politics did penetrate the working class in this period, although unevenly among its different strata.

Thus, the absence of successful revolutionary struggles other than the Russian Revolution cannot be explained by a lack of revolutionary situations. Lenin considered what social force, conditioned by features of the capitalist mode of production other than the erstwhile prosperity of past times, limited the workers’ class struggle and the development upon it of a political class consciousness. Cliff instead returned to the point from which Lenin had then set out — the revolutionary party intervening to overcome the separation, as confrontations with capital, of the economic and political struggle of the working class — but he turned the party’s task back to front, since the dominance of reformist consciousness in the mass of the working class must be overcome before it can struggle in a revolutionary manner.23

John Kelly, in Trade Unions and Socialist Politics, assessed Lenin’s analysis as “unsatisfactory”. Lenin, he said, was unclear about “under what conditions … well-paid workers play a reactionary role and under what conditions a progressive role.” He noted, for example, that Lenin discussed the metalworkers in the 1905 Russian revolution being not only “the best paid” but also “the most class conscious” part of the Russian proletariat.24

Kelly’s inability to discern how Lenin applied the theory of the labour aristocracy was partly a result of his view that Lenin believed “the long-term stagnation and decline of capitalism in the imperialist era … and its effects on workers’ living standards … would ultimately push them into support for socialism.”25 Lenin believed this, to a certain extent, with regard to the mass of the working class. He was confronted, however, by working-class movements, in countries such as England and Germany, which were, industrially and politically, the older and better organised ones, and yet they had united with their bourgeoisies in the war, rather than, as they had previously resolved, using this crisis “to rouse the people”, and they would go on to oppose revolutions.26 He perceived that, contrary to earlier expectations, the existence of opportunism within the working class is relatively resistant to the impact of the crises of capitalism: “The nearer the revolution approaches, the more strongly it flares up and the more sudden and violent the transitions and leaps in its progress, the greater will be the part the struggle of the revolutionary mass stream against the opportunist petty-bourgeois stream will play in the labour movement.”27

The theory of the labour aristocracy explains opportunism, not other forms of reformism. It distinguishes opportunism from the reformism of a working class that has no significant experience of struggle, is taking new steps in the class struggle, or is stepping back in the struggle in the middle of an expansionary phase of a capitalist long wave of development. It considers the effect of a common feature of all the countries where monopoly capitalism is based, rather than, for example, the peculiar (although not, in fact, absolutely distinctive) forces that Mike Davis, in his study of the political history of the US working class, observed had pulled apart the US labour movement28 and consolidated “a relationship between the American working class and American capitalism that stands in striking contrast to the balance of class forces in other capitalist states”, in which “the American working class … lacking any broad array of collective institutions or any totalizing agent of class consciousness (that is, a class party) has been increasingly integrated into American capitalism through the negativities of its internal stratification, its privatisation in consumption, and its disorganisation vis-à-vis political and trade-union bureaucracies”, instead of being politically “incorporated” through labour reformism.29 It shows that opportunism’s basis lies in the mode of production, rather than in the separation of economics and politics, but not in what are necessarily temporary periods of prosperity weakening the antagonism in the relationship between capital and wage labour. Instead, the basis of opportunism is the development, as a result of the combined and uneven development of capitalism as a whole, of monopoly relations in production among industries, regions and nations. These relations create superprofits, from which benefits for sections of workers can be supported.

The labour aristocracy, therefore, has a complex of interests. Its fundamental class interests stem from its exploitation by capital because it is part of the working class. It is also tied to its national bourgeoisie’s fortunes as monopoly capitalists because of the basis of its privileged position. Lenin summarised the economic roots and political and social significance of this in 1920:

Obviously, out of such enormous superprofits (since they are obtained over and above the profits which capitalists squeeze out of the workers of their “own” country) it is possible to bribe the labour leaders and the upper stratum of the labour aristocracy. And that is just what the capitalists of the “advanced” countries are doing: they are bribing them in a thousand different ways, direct and indirect, overt and covert.

This stratum of workers-turned-bourgeois, or the labour aristocracy, who are quite philistine in their mode of life, in the size of their earnings and in their outlook, is the principal prop of the Second International, and in our days, the principal social (not military) prop of the bourgeoisie. For they are the real agents of the bourgeoisie in the working-class movement, the labour lieutenants of the capitalist class, real vehicles of reformism and chauvinism. In the civil war between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie they inevitably, and in no small numbers, take the side of the bourgeoisie, the “Versaillais” against the “Communards.”30

According to Lenin, then, the relative privilege of the labour aristocracy is necessarily the basis for the existence of an opportunist trend in the working class. This argument does not, however, confirm Kelly’s suggestion that the theory of the labour aristocracy is, within Marxism, a “simple economic determinism”, in which the conditions of the productive sphere immediately determine other social phenomena, to which he contrasted a “complex economic determinism” of only ultimate determination by the sphere of production.31 This is only partly because the latter is involved in a conception of complex material determination in which political and ideological phenomena play their part, in particular with regard to the forms which historical struggles take, because, as Engels noted when he introduced a discussion of the “relative autonomy” of the these two spheres, “where there is division of labour on a social scale, the separate labour processes become independent of each other.” Also significant in this conception is the complementary (and necessary, because otherwise social phenomena do remain simply, if less immediately, reducible to their economic basis, with their political and ideological forms only mediating this) reason Engels gave:

History proceeds in such a way that the final result always arises from conflicts between many individual wills, and every one of them is in turn made into what it is by a host of particular conditions of life. Thus there are innumerable intersecting forces … and what emerges is something that no one intended.32

The significance of this combination is that not only is the relationship between a condition and an action not direct (Kelly elsewhere distinguishes between material interests and material practices as determinants, but does not consistently apply this33), but that the existence of various conditions of life implies the existence of various, conflicting actions, and the results of such conflict cannot be predetermined by the conditions of life and, also, in turn, affect them.

The theory of the labour aristocracy studies, in particular, the impact on that part of the working class of the interaction of two different social relations of production. This conditions a conflict of practices, including opportunism, within the stratum. The role of any particular group of these relatively privileged workers, however, is resolved only in the course of the class struggle.34

Lenin found inspiration for his theory of the labour aristocracy in comments made by Marx and Engels between 1858-92 on the opportunist and revolutionary trends in the English working class.35 Engels, for example, remarked that “the English proletariat is actually becoming more and more bourgeois”.36 He found repugnant a “bourgeois ‘respectability’, which has grown deep into the bones of the workers.”37 He also described the workers’ political thinking as the same as the bourgeoisie’s.38 Marx said that “almost all” the English working-class leaders “have sold themselves.”39 They contrasted the “skilled labourers”40 and textile workers41 — with their “‘old’ conservative trade unions, rich and therefore cowardly”42 who were “an aristocratic minority”43 that engaged in “a narrow circle of strikes for higher wages and shorter hours … as the ultimate goal”, excluded “all participation in any general activity of the working class as a class” so that “no real labour movement in the Continental sense exists”,44 were “quite remote” from the socialist movement that emerged in the 1880s,45 and were recognised as “the bourgeois labour party” in their opposition to a demand for eight hour day legislation46 — with a poorer and generationally newer majority of workers47 who eventually began an “utterly different” movement, still formally of trade unions but “mostly among the hitherto stagnant lowest strata”,48 which was “shaking up society far more profoundly and putting forward much more far-reaching demands … the people regard their immediate demands as only provisional, although they themselves do not yet know toward what final goal they are working. But this vague notion has a strong enough hold on them to make them elect as leaders only downright Socialists.”49 They also suggested these circumstances were connected to England’s monopoly of the world market and colonies.50

Engels linked the histories of the general condition of the working class, the situation of its better off sections, the characteristics of the leadership of the English working-class movement and the position of English industry in an 1885 article,51 the text of which he later incorporated into prefaces, with additional comments, of editions of his 1844 book on the condition of the working class.52 This persistent argument contradicts the claim made by Kevin Corr and Andy Brown that no consistent analysis of the labour aristocracy by Marx and Engels is evident53 as well as Tom O’Lincoln’s assertion that Marx and Engels “never reformulated their original ideas [of a straightforward development of workers’ struggles from unions confronting the capitalists to political opposition] in any systematic way.”54 Marx’s and Engels’ comments, at different times, did vary the emphasis in their argument, but their analysis developed into an often repeated theme55 of the relation between England’s domination of the world market and the corruption of the English working class.

According to Engels, a sharpening social crisis in the middle of the 1840s in England was resolved, in reaction to revolutions of 1848, by the political consolidation of capitalist class rule and the disorganisation and consequent collapse of the Chartist movement. Then a revival of trade initiated a new industrial epoch involving a world market, which at first consisted of agricultural countries grouped around England as the sole manufacturing centre: the renewal of economic prosperity was attributed to the victorious manufacturing capitalists' free trade policies. These two developments turned the working-class movement politically into the tail of the manufacturers’ Liberal Party, while the manufacturers had learned, in their struggle with Chartists over the priority of free trade as a national question, that they could “never obtain full social and political power over the nation except with the help of the working class.”56

Relations between the classes then gradually changed, Engels said. The capitalists submitted to the application and extension of the Factory Acts, recognised the legitimacy of the unions, and repealed the harshest laws governing workers’ relations to their employers. The Chartist political demands were partially implemented: suffrage was extended, the secret ballot implemented, the electoral boundaries reformed and payment of members introduced.

The mass of the working class experienced “temporary improvement” in their situation in the long boom from 1850 to 1870. This was, however, subject to reversal through the impact of unemployment and industrial restructuring.

Only two “protected” sections achieved a permanent improvement in their circumstances. Factory hands, through the legal limiting of the working day, gained sustainable living conditions and “a moral superiority, enhanced by their local concentration”; their strikes were now usually provoked by the manufacturers to cut production. Unions of skilled, “grown-up men” who had resisted competition from both cheaper labour and machinery had developed good relations with their employers and “enforc[ed] … a relatively comfortable position … [which] they accept as final.”57

As for “so-called workers’ representatives”, they were, Engels said, “people who are forgiven their being members of the working class because they themselves would like to drown their quality of being workers in the ocean of their liberalism.”58

From 1876, however, English industry stagnated as it was subjected to competition by the rise of other manufacturing nations. “The manufacturing monopoly … the pivot of the present social system of England”, was on the way out, and only England’s monopoly of colonial markets served as a buffer against collapse. The working class, which had shared (very unevenly) in the benefits of the monopoly, would lose its privileged position, not excluding “the privileged and leading minority”, Engels suggested. Therefore, socialism could and was already arising in England again, but the most important movement was “New Unionism”, which did not “look upon the wages system as … once-for-all established.”59

Marx and Engels, therefore, did not consider the labour aristocracy principally as a stratum in the working class. They were concerned about it as a shift in class relations that involved a historical connection of capitalist monopoly to opportunism. Changes in the political and sociological characteristics of the working class were a consequence of that.60

Contemporary political commentators on the phenomenon of the late nineteenth century labour aristocracy generally recognised its existence,61 but among twentieth century historians this was debated. Corr and Brown reviewed this discussion, critiquing the work of Eric Hobsbawm and John Foster, both of whom argued for the existence of a labour aristocracy. They concluded the labour aristocracy was not “the crucial element in explaining the change in class struggle” in the nineteenth century from the revolutionary Chartist movement of the first half to reformist trade unionism in the second half.62 Instead, they argued that the restabilisation and reorientation of the capitalist economy, the gradual but effective seizure of political control by the capitalists, and the defeats suffered by working-class movements in Britain and Europe in the 1840s compelled an adaptive reorientation of working-class politics to forms more restricted in scope and less able to mobilise mass working-class support: “The consequences of this for working class radicalism were very marked. It made the permanence of industrial capitalism for the foreseeable future a hard fact of life.” Therefore previous radical ideologies and their political forms “lost their relevance and appeal”, some forms of industrial struggle were excluded, and struggles at work were about wages and working conditions, not formal control of the means of production. “Political challenges to the system of established industrial capitalism … required [a] reconstitution of working class politics [which] took decades.”63

Corr and Brown’s argument has a number of weaknesses. It suggested they believed the working class must acquire revolutionary consciousness before a commitment to the struggle rather than first expressing its revolutionary character in its actions.64 Also, according to the reading of Hobsbawm and Foster by Corr and Brown, the two labour aristocracy advocates did not agree with Engels on the connection between monopoly power and its creation of superprofits and the labour aristocracy as a shift in class relations. Hobsbawm sought to establish the existence of a labour aristocracy by studying differences among workers across a range of measures of living standards and social status, before concluding “the relatively favourable terms [the labour aristocracy] got were to a large extent actually achieved at the expense of their less favoured colleagues, not merely at the expense of the rest of the world.”65 Foster related the higher wages of the labour aristocrats to “authority at work”, this being his differentiating feature for the stratum, which then became socially separated from the rest of the working class by its subculture.

Most significantly, the evidence Corr and Brown presented did not sustain a view contrary to Engels’. In opposition to the view that a relatively privileged section of the working class existed as a socially and politically significant stratum, they cited: the higher general wage levels of industries which had a larger proportion of high wage earners, and increases in general wage levels, to argue no break in the gradation of earnings can be identified that separates labour aristocrats from other workers; claims of high unemployment in many skilled trades in mid-nineteenth century London;66 the determination, according to Foster, of labour aristocrats’ wages “through the markets in response to union bargaining”,67 which, they said, was “a mechanism … suspiciously like that by which all wages are paid”; the insecurity of the position of the supposed labour aristocrats, demonstrated by their need for union organisation to defend their conditions; and the insignificant differences in the voting patterns of skilled and supervisory workers and unskilled workers found in a study of two cities, one dominated by textile industries, the other by engineering.

Engels had not confined the labour aristocracy to skilled workers, however: the factory hands he included were to be found in the leading industries, of which cotton was already established in 1848 and iron, steel and machine building were rising. The relative privilege, materially, of his labour aristocrats was only that their wages had risen above poverty levels, which provided the funds not only for a generally higher standard of living but also for these workers’ membership of benefit societies, cooperatives and unions (financially still dominated by benefit payments); their average unemployment was lower than for the rest of the class and their hours of works were reduced.

Robert Clough referred to two studies, conducted after the end of this period, that suggest significant differentiation in earnings and employment had developed, contrary to the claims of Corr and Brown: one found that in 1900 average skilled workers’ wages were forty shillings per week, those of unskilled workers were 20-25s and women and agricultural workers averaged 15s, while unskilled workers could expect three times higher unemployment, and less job security, than skilled workers; the other, from 1911 estimated “30 shillings per week was the minimum to sustain an adequate family existence, but five million out of eight million manual workers earned less than this: the average for these five million workers was 22 shillings.”68 With regard to working hours, Marx shows that in the middle of the 1860s the factory owners attempted to extend the 10-hour working day, regulated by the Factory Acts, by as much as an hour a day through “snatching a few minutes”, but that in parts of industries such as lace-making, potting, match-making, wallpaper production, baking, the railways, millinery and coal-mining, the working day could extend to up to 15 hours.69

Corr and Brown especially failed to recognise the political privileges of Victorian England’s labour aristocracy. The unions could not set the framework for overall wage determination when only a very small proportion of workers were organised. Union membership was only 600,000 out of about 10 million workers in the late 1850s and 1.5 million of 14 million people employed in trade and industry in 1892. This was in spite of the replacement of a “restricted legality” for unions by “a kind of official approval” for moderate unionism — the radicals of the working-class movement continued to suffer from government persecution70 — through legislation passed in 1855 and especially from 1868 to 1875, a situation only partly reversed by adverse judicial decisions in the 1890s which culminated in the 1901 Taff Vale judgment, which briefly made unions liable for damages from strike action. At the end of this period, the unions were still mostly the old craft unions, with the exception of the miners: the membership of the new unions fell from 300,000 in 1890 to 80,000 in 1896.71 These unions tended, moreover, in their defence of their members’ interests, to pursue exclusionary approaches: a jealous defence of job rights and trade customs, by the skilled men; against the Irish; and hostility among the old unions towards the “new unions”.72

Suffrage was similarly, if not quite as sharply, restricted, as was the exercise of the right to organise. The new residential and property qualifications of the 1867 Reform Act enfranchised 3 million; in 1884 the extension of the same qualifications to the counties created an electorate of 5 million. About half this electorate of (male) heads of households was now working class, but they were generally the older, more regularly employed and better paid workers. The mass of labourers, the casually employed and the unemployed were excluded.73 An estimate that “the vote was extended [in 1867] to only a minority of the working class (that is, to rather less than three in five of the urban wage earners)” accepts the exclusion of female and younger wage earners by the gender and age requirements of the reformed suffrage.74 This restricted franchise, not a division between skilled and unskilled workers who had the vote, was one of the fault lines between the labour aristocracy and the majority of the working class.

The workers who had the vote used this as a power in pursuit of their particular interests. Gordon Philips argued that their attachment to Liberalism

… should [not] be seen simply as a displacement of radical and working class politics; it marks, equally, the adaptation of Liberalism itself to working-class opinions and moods. Those wage earners who combined radicalism with respectability, at any rate, could find here a natural home. Liberalism, in the Gladstonian period, was not so remote from Chartism as to repel its former devotees … While not, of course, a party of the working class for itself, it was capable (at its urban base) of combining a thorough and vigorous notion of democratic government, a hatred of social privilege and an objection to monopolistic wealth, a disposition to prefer civil liberties to strenuous law enforcement, a strong leaning towards land reform, and an approval of at least some collectivist legislation on questions like factory hours, workmen’s trains and the control of the drink trade.75

According to Philips, “the weakness of Liberalism, as compared to Chartism, was its failure to embrace that large mass of wage earners who remained more or less beyond the reach of union, co-operative and Friendly Society.”76 Indeed, even in its adaptation to the working class, it did not try. Clough writes, “the free speech demonstrations in London in the late 1880s and the explosion of unskilled unionism in 1889-90 … drove sections of the working class into an alliance with Marxists and revolutionaries”, but, in opposition to these movements’ revolutionary methods, George Shipton, chairman of the London Trades Council, argued “when the people were unenfranchised, were without votes, the only power left to them was the demonstration of numbers. Now, however, the workmen have votes” — which ignored the restriction of the vote to only the better off male workers.77

When Corr and Brown instead attempted to find the labour aristocracy “in the forefront of radical politics” in England from the middle of the nineteenth century,78 they tended to further substantiate Engels’ position. This began with their agreement with Engels, who in 1851 wrote that the English bourgeoisie was “making use of the prosperity or semi-prosperity to buy the proletariat”79 (and whose 1858 remark about the “bourgeois proletariat”, referred to above, is, notably, about the whole class) on the general causes of political stabilisation at the beginning of the period. The political defeat of the Chartists was matched industrially by the earlier loss of craft control by the weavers and the spinners, and then “the decisive defeat of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers in the 1851 lockout [which] smashed the artisans in the industry, replacing them once and for all by the skilled worker in an established factory system.” At the same time, a new stage of industrialisation in, for example, iron and steel production, machinery and transport, replaced the situation where cotton was the only advanced industrial sector with a decisively broadened range and increase in volume of industrial production. With the boom, “real wages rose for the whole working class, albeit unevenly … Concessions were made by capital to secure a better incorporated working class displaying a degree of consent to its position.”80

According to Corr and Brown, “small but bitter” industrial disputes culminated in the 1859 builders’ strike, the wide support for which led to the establishment of the London Trades Council to organise solidarity. Skilled workers, they also pointed out, were involved in political activity in support of the North in the US Civil War (while the cotton factory owners favoured the South), and the 1863 Polish uprising and their unions took part in the founding of the International Workingman’s Association (IWA).

At this point, however, the two fall silent.

Corr and Brown’s inability to recognise the significance of this silence stemmed from not considering the problem for the bourgeoisie that Engels perceived: “[Its] advantage, once gained, had to be perpetuated.”81 The artisanal labour aristocracy of the first half of the nineteenth century, whose social conditions Marx and Engels distinguished clearly from those of “the mass of the workers who live in truly proletarian conditions,”82 despite the claim of Corr and Brown that this contrast was a “very imprecise” identification,83 was defeated and dissolved.

The boom could not eliminate capitalism’s contradictions or class antagonisms, however. The working-class movement started to develop spontaneously again, largely where, because of the relatively favourable employment conditions resulting from a need for skills or the leading character of the industry, the working class was best placed to organise. The capitalist class responded to this change in the balance of forces in the class struggle with concessions on legal rights to organise unions and to vote and with other actions that helped to forge a new relationship between this section of the working class and the capitalist class.

The Reform League, formed in 1865 to demand universal male suffrage and the secret ballot and led by middle-class radicals and workers, including members of the General Council of the IWA, soon received support from Liberal politicians and manufacturers: it compromised its demands by a qualification that voters should be “registered and residential”. The trade union leaders in the league were then paid to mobilise the working-class vote for the Liberals in the 1868 election.

The trade union leaders also found common cause with the Liberal politicians on Ireland, defending Prime Minister Gladstone in his suppression of the Fenian movement. The IWA, meanwhile, organised mass demonstrations in support of the Fenians.84 Engels commented: “The masses are for the Irish. The organisations and labour aristocracy in general follow Gladstone and the liberal bourgeoisie.”85

Engels thus showed how those elements in the English working class that were active in the class struggle in the period after the class’s political defeat in 1848 became a new labour aristocracy, a relatively privileged section of the class that supported England’s imperial rule, adopted a political party of the bourgeoisie as its own and excluded other workers from their more protected position. In particular, he identified as the basis for this connection of the labour aristocracy to such class-collaborationist politics, the superprofits from the English industrial and colonial monopoly, which supported the benefits of the stratum.

Engels had only one, apparently temporary, example of monopoly capitalism, however. This was not sufficient to fully grasp the features of this economic form or the framework of the class struggle in the era of monopoly capitalism. This, according to Max Elbaum and Robert Seltzer, led Engels to underestimate the capacity of English capital to transform its monopoly power and also the strength of the material basis of opportunism among English workers.86 The contribution Lenin made to the theory of the labour aristocracy, after the consolidation of monopoly capitalism, was to address the transformation of the character of monopoly capitalism when it become the general form of the capitalist mode of production and the consequences of this for revolutionary politics in the working-class movement.

V.I. Lenin, “Imperialism and the Split in Socialism”, in Imperialism—the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Resistance Books, Sydney, 1991, p. 131.

V.I. Lenin, “In Australia”, Collected Works, , Vol. 19, pp. 216-17.

V.I. Lenin, “Imperialism and the Split in Socialism”, ibid., Vol. 23, p. 128.

V.I. Lenin, “The Collapse of the Second International”, LCW, Vol. 21, p. 242.

V.I. Lenin, “Opportunism and the Collapse of the Second International”, LCW, Vol. 22, p. 112.

Lenin, “Imperialism and the Split in Socialism”, pp. 132-34.

Lenin, “The Collapse of the Second International”, pp. 242-43.

Lenin, “Opportunism and the Collapse of the Second International”, p. 111. This formulation did not refer to the labour aristocracy. In relation to the European examples Lenin was discussing, however, the labour aristocracy did not exist until towards the last decade of this period. Within a few paragraphs, he pointed out that opportunism’s class basis is “the alliance of a small section of privileged workers with ‘their’ national bourgeoisie against the working-class masses” (ibid., p. 112).

Lenin, “The Collapse of the Second International”, p. 244.

Lenin, “Imperialism and the Split in Socialism”, p. 128.

Grigory Zinoviev, “The Social Roots of Opportunism”, in John Riddell (ed.), Lenin's Struggle for a Revolutionary International, Monad Press, New York, 1984, pp. 483-84.

Karl Marx, “Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy”, in Karl Marx, and Frederick Engels, Marx-Engels Selected Works, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1977, Vol. 1, pp. 503-04.

Zinoviev’s survey, for example, cites the petty bourgeoisie as one of three sources of opportunism. (op. cit., pp. 475-80, 494).

Perry Anderson, for example, considered the “representative state … the ideological linchpin of Western capitalism” because, he argued, it generated a “belief by the masses that they exercise an ultimate self-determination within the existing social order” (“The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci”, New Left Review, 100, 1976-77, p. 28). Ellen Meiksins Wood, alternatively, stressed an apparent depoliticisation of domination and exploitation in the relations of production (“The Separation of the Economic and the Political in Capitalism”, New Left Review, 127).

Max Elbaum and Robert Seltzer, “The Labor Aristocracy: The Material Basis for Opportunism in the Labor Movement”, Line of March, May-June 1982, p. 62.

V.I. Lenin, “What is to Be Done?”, LCW, Vol. 5, p. 512.

Elbaum and Seltzer, op. cit., p. 81.

Lenin, “Imperialism and the Split in Socialism”, pp. 134.

See Robert Clough, “Watchdogs of Capitalism: the Reality of the Labour Aristocracy”, Fight Racism, Fight Imperialism, 116, December1993/January 1994.

V.I. Lenin, “The Discussion on Self-Determination Summed Up”, LCW, Vol. 22, p. 343.

Tony Cliff, “Economic Roots of Reformism”, http://www.marxist.org/archive/cliff/1957/06/rootsref.htm

On long waves of capitalist development, see Ernest Mandel, Late Capitalism, Verso, London, 1987, Ch. 4.

Clough, op. cit.

John Kelly, Trade Unions and Socialist Politics, Verso, London, 1988, pp. 33-34. Kelly, despite the errors discussed here, provides a valuable study of Marxism’s classical ideas and contemporary debates on the relationship of the working class’s organisation for economic struggle to its political struggle and, in particular, of strike waves and workers’ political radicalisation in Britain (Ch. 5).

Kelly, op. cit., p. 34

Elbaum and Seltzer, op. cit., p. 63.

Lenin, “Imperialism and the Split in Socialism”, p. 135.

Mike Davis, Prisoners of the American Dream, Verso, London, 1988, Chs. 1-2, especially pp. 20-29.

Ibid., pp. 7-8.

V.I. Lenin, “Preface to the French and German editions: Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism”, op. cit., p. 31.

Kelly, op. cit., pp. 15-18.

Frederick Engels in a series of letters, “To Conrad Schmidt, August 5, 1890”, “To J. Bloch in Konigsberg, September 21-22, 1890”, “To Conrad Schmidt, October 27, 1890”, “To Franz Mehring, July 14, 1893” and “To W. Borgius, January 25, 1894”, all in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Selected Correspondence, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1982 [hereafter MESC]. In these letters Engels refers his readers to, as accounts of the theory and examples of its application, Marx's Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte and many allusions in Capital and his own Anti-Duhring and Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy.

Kelly, op. cit., pp. 165-66.

Elbaum and Seltzer, op. cit., pp. 80-81.

V.I. Lenin, “Imperialism and the Split in Socialism”, p. 129.

Friedrich Engels, “To Marx, October 7, 1858”, MESC, p. 103.

Friedrich Engels, “To Friedrich Adolph Sorge, December 7, 1889”, in MESC, p. 386

Friedrich Engels, “To Karl Kautsky, September 12, 1882”, MESC, p. 330.

Friedrich Engels, “On the Hague Congress of the International”, in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works [hereafter MECW], Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1988, vol. 23, p. 265. Engels is reporting Marx’s words.

Friedrich Engels, “To Friedrich Adolph Sorge, December 7, 1889”, MESC, p. 385.

Friedrich Engels, “To Friedrich Adolph Sorge, September 14, 1891”, in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Letters to Americans, International Publishers, New York, 1969, p. 236.

Friedrich Engels, “To Friedrich Adolph Sorge, March 4, 1891”, cited in Lenin, “Imperialism and the Split in Socialism”, p. 130

Karl Marx, “Records of Marx’s Speeches on Trade Unions: From the Minutes of the Session of the London Conference of the International Working Men’s Association on September 20, 1871”, in MECW, Vol. 22, p. 614.

Friedrich Engels, “To Eduard Bernstein, June 17, 1879”, MESC, p. 301. See also Friedrich Engels, “To August Bebel, August 30, 1883”, MESC, p. 343.

Friedrich Engels, “To August Bebel, January 18, 1884”, in MESC, p. 348.

Friedrich Engels, “To Friedrich Adolph Sorge, September 14, 1891”, p. 236.

Karl Marx, “Records of Marx’s Speeches on Trade Unions”, in MECW, Vol. 22, p. 614.

Friedrich Engels, “To Friedrich Adolph Sorge, April 19, 1890”, MESC, p. 390.

Friedrich Engels, “To Friedrich Adolph Sorge, December 7, 1889”, in MESC, p. 385.

Friedrich Engels, “To Karl Kautsky, September 12, 1882”, p. 331. See also Engels, “To Marx, October 7, 1858”, MESC, p. 103, and Engels, “To August Bebel, August 30, 1883”, MESC, p. 344.

Friedrich Engels, “England in 1845 and 1885”, in MECW, vol. 26, pp. 295-301.52. Friedrich Engels, “Preface to The Condition of the Working Class in England”, MESW, Vol. 3, pp. 440-452.

Frederick Engels, "Preface to The Condition of the Working Class in England", MESW, Vol. 3, pp. 440-452.

Kevin Corr and Andy Brown, “The Labour Aristocracy and the Roots of Reformism”, International Socialism, 59, Summer 1993, p. 39.

Tom O’Lincoln, “Trade Unions and Revolutionary Oppositions: a Survey of Classic Marxist Writings”, http://www.anu.edu.au/polsci/marx/intros/ol-tu.htm, n.d., p. 1. O’Lincoln tries to add weight to this assertion by reference to Engels’ view that the links he had identified giving rise to the conservative development of the unions were only temporary.

Corr and Brown, op. cit., p. 43.

MESW, Vol. 3, p. 446.

Ibid., p. 448.

Ibid., p. 452.

Ibid., pp. 449-51.

cf. Clough, “Watchdogs of Capitalism”.

Robert Clough, “Haunted by the Labour Aristocracy: Marx and Engels on the Split in the Working Class”, Fight Racism, Fight Imperialism, 115, October/November 1993

Corr and Brown, op. cit., pp. 50-51 and 54-67. The earlier part of their article, which examines the texts of Marx, Engels and Lenin on the labour aristocracy, setting the scene (particularly by attempting to differentiate Marx’s views from those of Lenin) for their substantive argument, is criticised in Clough, “Haunted by the Labour Aristocracy” and “Watchdogs of Capitalism”.

Ibid., pp. 67-70.

Clough, “Watchdogs of Capitalism”.

Eric Hobsbawm, Labouring Men, p. 322, cited by Corr and Brown, op. cit., p. 61.

Mayhew, in E.P. Thompson and E. Yeo, The Unknown Mayhew, p. 566, cited in Corr and Brown, op. cit., p. 57. This claim is unusual, at least in its emphasis. Most commentators refer to higher, “full” employment, at least for most of the boom period 1850-1870: see, for example, Gordon Phillips, “The British Labour Movement before 1914”, in Dick Geary (ed.), Labour and Socialist Movements in Europe before 1914, Berg, Providence and Oxford, 1992. Elbaum and Seltzer stress the relatively good employment situation of the labour aristocracy even after 1876 (op. cit., p. 67).

John Foster, “British Imperialism and the Labour Aristocracy”, in J. Skelley (ed), 1926: The General Strike, p. 18, cited in Corr and Brown, op. cit., p. 66.

Robert Clough, Labour, a Party Fit for Imperialism, Larkin Publications, London, 1992, pp. 12-13 and 19-20.

Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1986, vol. 1, chs. 10 and 25.

Phillips, op. cit., p. 39.

Clough, Labour, pp. 20-21, and Phillips, op. cit., pp. 36 and 38.

Clough, Labour, p. 21, Elbaum and Seltzer, op. cit., p. 66, and Phillips, op. cit., p. 40.

Clough, Labour, pp. 14, 20-21.

Philips, op. cit., p. 39.

Ibid., p. 42.

Ibid., p. 42. Philips then notes this was “a weakness, likewise, of socialism and of the early Labor Party” (p. 42). Likeness of result does not indicate likeness of cause, however: the socialists struggled to gain any support, while the Labor Party was supported by the labour aristocracy instead.

Clough, Labour, p. 21.

Corr and Brown, op. cit., p. 58.

Friedrich Engels, “To Marx, February 5, 1851”, in MECW, vol. 38, p. 281.

Corr and Brown, op. cit., pp. 67-68.

Engels, “Preface to The Condition of the Working Class in England”, p. 446.

Karl Marx, and Friedrich Engels, “Review: May to October [1850]”, MECW, Vol. 10, p. 514.

Corr and Brown, op. cit., p. 41.

Clough, Labour, pp. 13-14.

Friedrich Engels, “From an Interview with Engels Published in the New Yorker Volkszeitung”, in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Ireland and the Irish Question, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1978, p. 460.

Elbaum and Seltzer, op. cit., pp. 66-67.