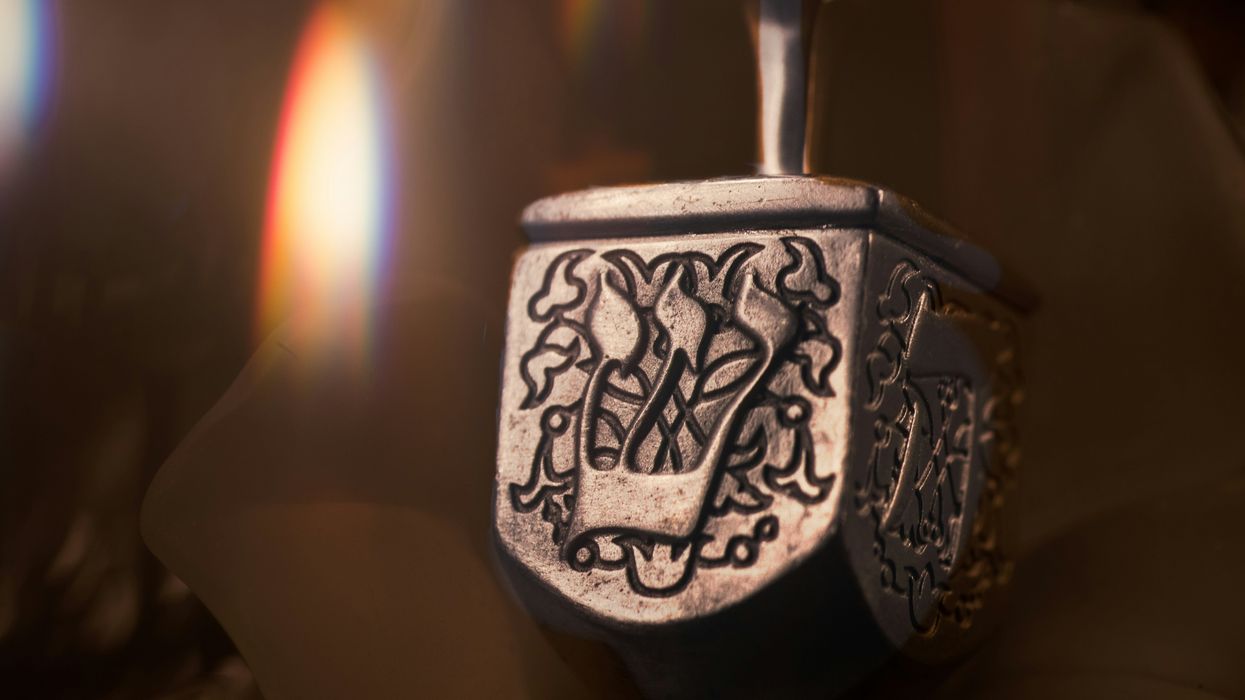

Photo by Robert Zunikoff on Unsplash

Hanukkah may be the best known Jewish holiday in the United States. But despite its popularity in the U.S., Hanukkah is ranked one of Judaism’s minor festivals, and nowhere else does it garner such attention. The holiday is mostly a domestic celebration, although special holiday prayers also expand synagogue worship.

So how did Hanukkah attain its special place in America?

Hanukkah’s back story

The word “Hanukkah” means dedication. It commemorates the rededicating of the ancient Temple in Jerusalem in 165 B.C. when Jews – led by a band of brothers called the Maccabees – tossed out statues of Hellenic gods that had been placed there by King Antiochus IV when he conquered Judea. Antiochus aimed to plant Hellenic culture throughout his kingdom, and that included worshipping its gods.

Legend has it that during the dedication, as people prepared to light the Temple’s large oil lamps to signify the presence of God, only a tiny bit of holy oil could be found. Yet, that little bit of oil remained alight for eight days until more could be prepared. Thus, each Hanukkah evening, for eight nights, Jews light a candle, adding an additional one as the holiday progresses throughout the festival.

Hanukkah’s American story

Today, America is home to almost 7 million Jews. But Jews did not always find it easy to be Jewish in America. Until the late 19th century, America’s Jewish population was very small and grew to only as many as 250,000 in 1880. The basic goods of Jewish religious life – such as kosher meat and candles, Torah scrolls, and Jewish calendars – were often hard to find.

In those early days, major Jewish religious events took special planning and effort, and minor festivals like Hanukkah often slipped by unnoticed.

My own study of American Jewish history has recently focused on Hanukkah’s development.

It began with a simple holiday hymn written in 1840 by Penina Moise, a Jewish Sunday school teacher in Charleston, South Carolina. Her evangelical Christian neighbors worked hard to bring the local Jews into the Christian fold. They urged Jews to agree that only by becoming Christian could they attain God’s love and ultimately reach Heaven.

Moise, a famed poet, saw the holiday celebrating dedication to Judaism as an occasion to inspire Jewish dedication despite Christian challenges. Her congregation, Beth Elohim, publicized the hymn by including it in their hymnbook.

This English language hymn expressed a feeling common to many American Jews living as a tiny minority. “Great Arbiter of human fate whose glory ne'er decays,” Moise began the hymn, “To Thee alone we dedicate the song and soul of praise.”

It became a favorite among American Jews and could be heard in congregations around the country for another century.

Shortly after the Civil War, Cincinnati Rabbi Max Lilienthal learned about special Christmas events for children held in some local churches. To adapt them for children in his own congregation, he created a Hanukkah assembly where the holiday’s story was told, blessings and hymns were sung, candles were lighted and sweets were distributed to the children.

His friend, Rabbi Isaac M. Wise, created a similar event for his own congregation. Wise and Lilienthal edited national Jewish magazines where they publicized these innovative Hanukkah assemblies, encouraging other congregations to establish their own.

Lilienthal and Wise also aimed to reform Judaism, streamlining it and emphasizing the rabbi’s role as teacher. Because they felt their changes would help Judaism survive in the modern age, they called themselves “Modern Maccabees.” Through their efforts, special Hanukkah events for children became standard in American synagogues.

20th-century expansion

By 1900, industrial America produced the abundance of goods exchanged each Dec. 25. Christmas’ domestic celebrations and gifts to children provided a shared religious experience to American Christians otherwise separated by denominational divisions. As a home celebration, it sidestepped the theological and institutional loyalties voiced in churches.

For the 2.3 million Jewish immigrants who entered the U.S. between 1881 and 1924, providing their children with gifts in December proved they were becoming American and obtaining a better life.

But by giving those gifts at Hanukkah, instead of adopting Christmas, they also expressed their own ideals of American religious freedom, as well as their own dedication to Judaism

After World War II, many Jews relocated from urban centers. Suburban Jewish children often comprised small minorities in public schools and found themselves coerced to participate in Christmas assemblies. Teachers, administrators and peers often pressured them to sing Christian hymns and assert statements of Christian faith.

From the 1950s through the 1980s, as Jewish parents argued for their children’s right to freedom from religious coercion, they also embellished Hanukkah. Suburban synagogues expanded their Hanukkah programming.

As I detail in my book, Jewish families embellished domestic Hanukkah celebrations with decorations, nightly gifts and holiday parties to enhance Hanukkah’s impact. In suburbia, Hanukkah’s theme of dedication to Judaism shone with special meaning. Rabbinical associations, national Jewish clubs and advertisers of Hanukkah goods carried the ideas for expanded Hanukkah festivities nationwide.

In the 21st century, Hanukkah accomplishes many tasks. Amid Christmas, it reminds Jews of Jewish dedication. Its domestic celebration enhances Jewish family life. In its similarity to Christmas domestic gift-giving, Hanukkah makes Judaism attractive to children and – according to my college students – relatable to Jews’ Christian neighbors. In many interfaith families, this shared festivity furthers domestic tranquility.

In America, this minor festival has attained major significance.

Dianne Ashton, Professor of Religion, Rowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.