A portrait of John Birch hangs in an office cubicle at the headquarters of the John Birch Society in Appleton, Wis., Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022. The once-powerful John Birch Society is largely forgotten today, relegated to a pair of squat buildings along a busy commercial street in small-town Wisconsin. But that is only part of their story. Because outside those cramped little offices is a national political landscape that the Society helped forge. (AP Photo/David Goldman)Read More

Executive Senior Editor Steve Bonta, left, and writer Daniel Natal, with the John Birch Society’s New American magazine, film a live broadcast at the organization’s headquarters in Appleton, Wis., Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022. Back when the Cold War was looming and TV was still mostly in black and white, the Society was a powerful presence in American life. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

CEO Bill Hahn watches a live broadcast from a production booth at the headquarters of the John Birch Society in Appleton, Wis., Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

An employee walks through a library at the headquarters of the John Birch Society in Appleton, Wis., Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

BY TIM SULLIVAN

APPLETON, Wis. (AP) — The decades fall away as you open the front doors.

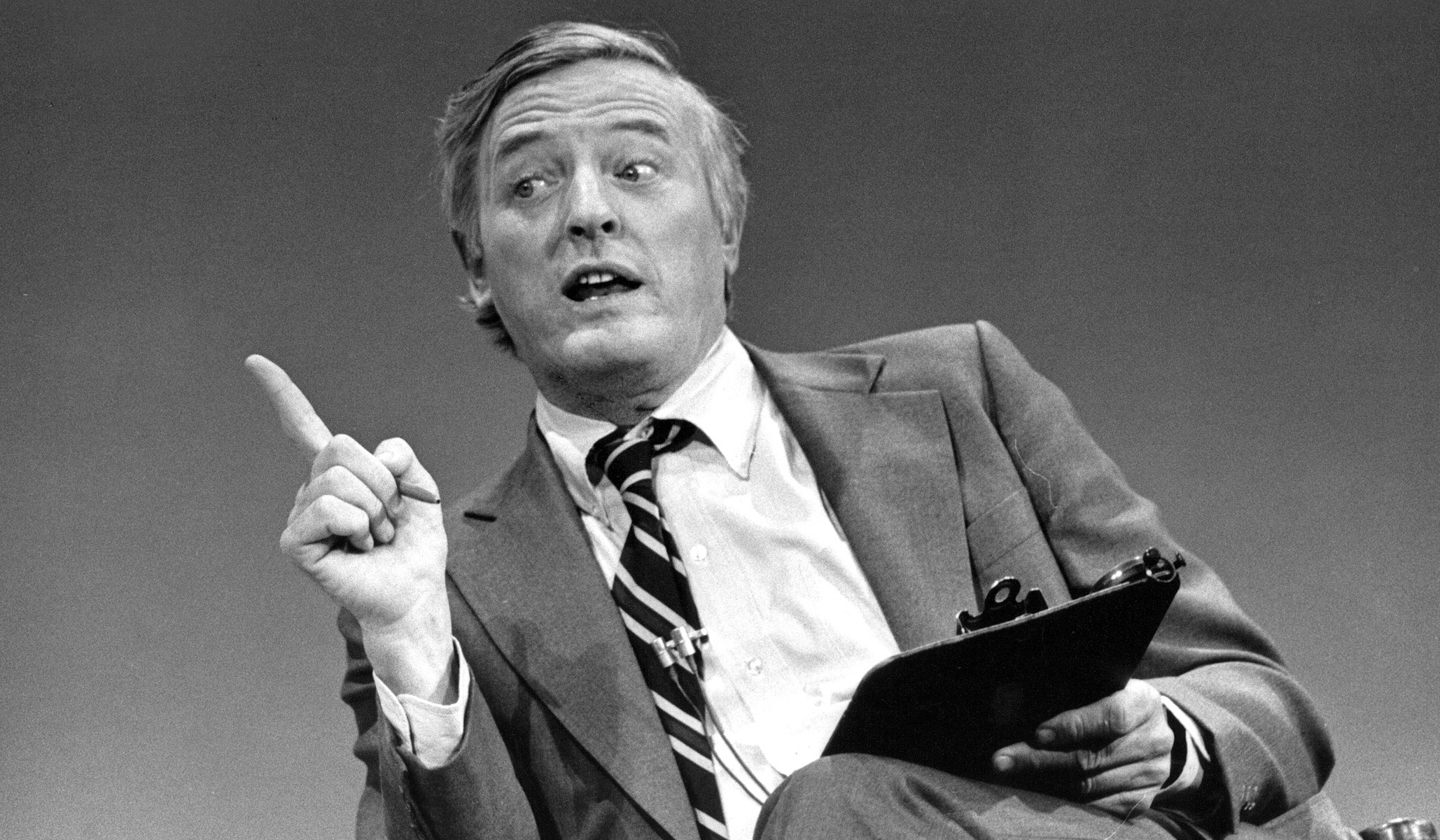

It’s the late 1950s in the cramped little offices — or maybe the pre-hippie 1960s. It’s a place where army-style buzz cuts are still in fashion, communism remains the primary enemy and the decor is dominated by American flags and portraits of once-famous Cold Warriors.

At the John Birch Society, they’ve been waging war for more than 60 years against what they’re sure is a vast, diabolical conspiracy. As they tell it, it’s a plot with tentacles that reach from 19th-century railroad magnates to the Biden White House, from the Federal Reserve to COVID vaccines.

Long before QAnon, Pizzagate and the modern crop of politicians who will happily repeat apocalyptic talking points, there was Birch. And outside these cramped small-town offices is a national political landscape that the Society helped shape.

“We have a bad reputation. You know: ‘You guys are insane,’” says Wayne Morrow, a Society vice president. He is standing in the group’s warehouse amid 10-foot (3-meter) shelves of Birch literature waiting to be distributed.

“But all the things that we wrote about are coming to pass.”

___

Back when the Cold War loomed and TV was still mostly in black and white, the John Birch Society mattered. There were dinners at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York and meetings with powerful politicians. There was a headquarters on each coast, a chain of bookstores, hundreds of local chapters, radio shows, summer camps for members’ children.

A chair sits at the end of a row of file cabinets at a library in the John Birch Society headquarters in Appleton, Wis., Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Well-funded and well-organized, they sent forth fevered warnings about a secret communist plot to take over America. It made them heroes to broad swaths of conservatives, even as they became a punchline to a generation of comedians.

“They created this alternative political tradition,” says Matthew Dallek, a historian at George Washington University and author of “Birchers: How the John Birch Society Radicalized the American Right.” He says it forged a right-wing culture that fell, at first, well outside mainstream Republican politics.

Conspiracy theories have a long history in the United States, going back at least to 1800, when secret forces were said to be backing Thomas Jefferson’s presidential bid. It was a time when such talk moved slowly, spread through sermons, letters and tavern visits.

No more. Fueled by social media and the rise of celebrity conspiracists, the last two decades have seen ever-increasing numbers of Americans lose faith in everything from government institutions to journalism. And year after year, ideas once relegated to fringe newsletters, little-known websites and the occasional AM radio station pushed their way into the mainstream.

CEO Bill Hahn points to articles of the Constitution in his office during an interview at the headquarters of the John Birch Society in Appleton, Wis., Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Today, outlandish conspiracy theories are quoted by more than a few U.S. senators, and millions of Americans believe the COVID pandemic was orchestrated by powerful elites. Prominent cable news commentators speak darkly of government agents seizing citizens off the streets.

But the John Birch Society itself is largely forgotten, relegated to a pair of squat buildings along a busy commercial street in small-town Wisconsin.

So why even take note of it today? Because many of its ideas — from anger at a mysterious, powerful elite to fears that America’s main enemy was hidden within the country, biding its time — percolated into pockets of American culture over the last half-century. Those who came later simply out-Birched the Birchers. Says Dallek: “Their successors were politically savvier and took Birch ideas and updated them for contemporary politics.”

The result has been a new political terrain. What was once at the edges had worked its way toward the heart of the discourse.

To some, the fringe has gone all the way to the White House. In the Society’s offices, they’ll tell you that Donald Trump would never have been elected if they hadn’t paved the way.

Boxes of John Birch Society literature waiting to be distributed pamphlets and reports on a range of issues from COVID to inflation are stored in a warehouse at the headquarters of the John Birch Society in Appleton, Wis., Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

“The bulk of Trump’s campaign was Birch,” Art Thompson, a retired Society CEO who remains one of its most prominent voices, says proudly. “All he did was bring it out into the open.”

There’s some truth in that, even if Thompson is overstating things.

The Society had spent decades calling for a populist president who would preach patriotism, oppose immigration, pull out of international treaties and root out the forces trying to undermine America. Trump may not have realized it, but when he warned about a “Deep State” — a supposed cabal of bureaucrats that secretly controls U.S. policy — he was repeating a longtime Birch talking point.

A savvy reality TV star, Trump capitalized on a conservative political landscape that had been shaped by decades of right-wing talk radio, fears about America’s seismic cultural shifts and the explosive online spread of misinformation.

While the Birch Society echoes in that mix, tracing those echoes is impossible. It’s hard to draw neat historical lines in American politics. Was the Society a prime mover, or a bit player? In a nation fragmented by social media and offshoot groups by the dozens, there’s just no way to be sure. What is certain, though, is this:

“The conspiratorial fringe is now the conspiratorial mainstream,” says Paul Matzko, a historian and research fellow at the libertarian-leaning Cato Institute. “Right-wing conspiracism has simply outgrown the John Birch Society.”

___

Their beliefs skip along the surface of the truth, with facts and rumors and outright fantasies banging together into a complex mythology. “The great conspiracy” is what Birch Society founder Robert Welch called it in “The Blue Book,” the collection of his writings and speeches still treated as near-mystical scripture in the Society’s corridors.

Wayne Morrow, vice president of the John Society, walks past a world map hanging in a warehouse storing the organization’s literature, stickers and buttons at its headquarters in Appleton, Wis., Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Welch, a wealthy candy company executive, formed the Society in the late 1950s, naming it for an American missionary and U.S. Army intelligence officer killed in 1945 by communist Chinese forces. Welch viewed Birch as the first casualty of the Cold War. Communist agents, he said, were everywhere in America.

Welch shot to prominence, and infamy, when he claimed that President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the hero general of World War II, was a “dedicated, conscious agent of the Communist conspiracy.” Also under Kremlin control, Welch asserted: the secretary of state, the head of the CIA, and Eisenhower’s younger brother Milton.

Subtlety has never been a strong Birch tradition. Over the decades, the Birch conspiracy grew to encompass the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, public education, the United Nations, the civil rights movement, The Rockefeller Foundation, the space program, the COVID pandemic, the 2020 presidential election and climate-change activism. In short, things the Birchers don’t like.

The plot’s leaders — “insiders,” in Society lexicon — range from railroad baron Cornelius Vanderbilt to former President George H.W. Bush and Bill Gates, whose vaccine advocacy is, they say, part of a plan to control the global population. While his main focus was always communism, Welch eventually came to believe that the conspiracy’s roots twisted far back into history, to the Illuminati, an 18th-century Bavarian secret society.

By the 1980s, the Society was well into its decline. Welch died in 1985 and the society’s reins passed to a series of successors. There were internal revolts. While its aura has waned, it is still a force among some conservatives — its videos are popular in parts of right-wing America, and its offices include a sophisticated basement TV studio for internet news reports. Its members speak at right-wing conferences and work booths at the occasional county fair.

Scholars say its ranks are far reduced from the 1960s and early 1970s, when membership estimates ranged from 50,000 to 100,000. “Membership is something that has been closely guarded since day one,” says Bill Hahn, who became CEO in 2020. He will only say the organization “continues to be a growing operation.

Today, the Society frames itself as almost conventional. Almost.

“We have succeeded in attracting mainstream people,” says Steve Bonta, a top editor for the Society’s New American magazine. The group has toned down the rhetoric and is a little more careful these days about throwing around accusations of conspiracies. But members still believe in them fiercely.

“As Mr. Welch came out with on Day One: There is a conspiracy,” Hahn says. “It’s no different today than it was back in December 1958.”

It can feel that way. Ask about the conspiracy’s goal, and things swerve into unexpected territory. The sharp rhetoric re-emerges and, once again, the decades seem to fall away.

“They really want to cut back on the population of the Earth. That is their intent,” Thompson says.

But why?

“Well, that’s a good question, isn’t it?” he responds. “It makes no sense. But that’s the way they think.”

___

Follow AP National Writer Tim Sullivan on Twitter at http://twitter.com/ByTimSullivan