India and Pakistan fought 3 wars over Kashmir – here’s why international law and US help can’t solve this territorial dispute

An armed conflict in Kashmir has thwarted all attempts to solve it for three quarters of a century.

Kashmir, an 85,806-square-mile valley between the snowcapped Himalaya and Karakoram mountain ranges, is a contested region between India, Pakistan and China. Both India and Pakistan lay claim to all of Kashmir, but each administers only part of it.

Map of Kashmir. Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, 2002, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

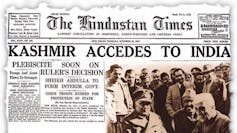

During the British rule of India, Kashmir was a feudal state with its own regional ruler. In 1947, the Kashmiri ruler, Maharaja Hari Singh, agreed that his kingdom would join India under certain conditions. Kashmir would retain political and economic sovereignty, while its defense and external affairs would be dealt with by India.

But Pakistan, newly created by the British, laid claim to a majority-Muslim part of Kashmir along its border. India and Pakistan fought the first of three major wars over Kashmir in 1947. It resulted in the creation of a United Nations-brokered “ceasefire line” that divided Indian and Pakistani territory. The line went right through Kashmir.

Get your news from people who know what they’re talking about.Sign up for newsletter

Despite the establishment of that border, presently known as the “Line of Control,” two more wars over Kashmir followed, in 1965 and 1999. An estimated 20,000 people died in these three wars.

International law, a set of rules and regulations created after World War II to govern all the world’s nation-states, is supposed to resolve territorial disputes like Kashmir. Such disputes are mainly dealt with by the International Court of Justice, a United Nations tribunal that rules on contested borders and war crimes.

Yet international law has repeatedly failed to resolve the Kashmir conflict, as my research on Kashmir and international law shows.

International law fails in Kashmir

The U.N. has made many failed attempts to restore dialogue after fighting between India and Pakistan over Kashmir, which today is home to a diverse population of 13.7 million Muslims, Hindus and people of other faiths.

In 1949, the U.N. sent a peacekeeping mission to both countries. U.N. peace missions were not as robust as its peacekeeping operations are today, and international troops proved unable to protect the sanctity of the borders between India and Pakistan.

In 1958, the Graham Commission, led by a U.N.-designated mediator, Frank Graham, recommended to the U.N. Security Council that India and Pakistan agree to demilitarize in Kashmir and hold a referendum to decide the status of the territory.

India rejected that plan, and both India and Pakistan disagreed on how many troops would remain along their border in Kashmir if they did demilitarize. Another war broke out in 1965.

In 1999, India and Pakistan battled along the Line of Control in the Kargil district of Kashmir, leading the United States to intervene diplomatically, siding with India.

Since then, official U.S. policy has been to prevent further escalation in the dispute. The U.S. government has offered several times to facilitate a mediation process over the contested territory.

The latest U.S. president to make that offer was Donald Trump after conflict erupted in Kashmir in 2019. The effort went nowhere.

Why international law falls short

Why is the Kashmir conflict too politically difficult for a internationally brokered compromise?

The maharaja of Kashmir agreed to join India in 1947.

For one, India and Pakistan don’t even agree on whether international law applies in Kashmir. While Pakistan considers the Kashmir conflict an international dispute, India says it is a “bilateral issue” and an “internal matter.”

India’s stance narrows the purview of international law. For example, regional organizations like the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation cannot intervene on the Kashmir issue – by convening a regional dialogue, for example – because its charter prohibits involvement in “bilateral and contentious issues.”

But India’s claim that Kashmir is Indian territory is hotly debated.

In 2019, the Indian government abolished the 1954 law that gave Kashmir autonomous status and militarily occupied the territory. At least 500,000 Indian troops are in Kashmir today.

Pakistan’s government denounced the move as “illegal,” and many Kashmiris on both sides of the Line of Control say India violated its 1947 accession deal with Maharaja Singh.

The U.N. still officially considers Kashmir a disputed area. But India has held firm that Kashmir is part of India, under central government control, worsening already bad relations between India and Pakistan.

Military coups and terror

Another obstacle to peace between the two nations: Pakistan’s military.

In 1953, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistani Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra agreed in principle to resolve the Kashmir problem through a U.N. mediation or with an International Court of Justice proceeding.

That never happened, because the Pakistani military overthrew Ali Bogra in 1955.

Several more Pakistani military regimes have interrupted Pakistani democracy since then. India believes these non-democratic regimes lack credibility to negotiate with it. And, generally, Pakistan’s military governments have preferred the battlefield over political dialogue.

Terrorism is another critical factor making the Kashmir situation more complex. Several radical Islamist groups, including Lashkar-e-Toiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed, operate in Kashmir, based primarily on the Pakistani side.

Since the late 1980s the terrorist groups have conducted targeted strikes and attacks on Indian government and military facilities, leading the Indian military to retaliate in Pakistani territory. Pakistan then alleges that India has breached the borderline, defying international treaties like the 1972 Simla Agreement to conduct its anti-terror attacks.

In many cases, treaties and international court decisions cannot be enforced. There is no international police force to help implement international law.

If a country ignores an International Court of Justice ruling, the other party in that court case may have recourse to the Security Council, which can pressure or even sanction a nation to comply with international law.

But that rarely happens, as such resolution processes are highly political and any permanent Security Council member can veto them.

And when conflicting parties are more inclined to view a conflict through the lens of domestic law – as India views Kashmir and Israel views the Palestinian territories – they can argue that international law simply does not apply.

Kashmir is not the only contested territory where international law has failed.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict over the Gaza and West Bank territories is another example. For decades, both the U.N. and the United States have repeatedly and unsuccessfully intervened there in an effort to establish mutually acceptable borderlines and bring peace.

International law has grown and strengthened since its creation in the 1940s, but there are still many problems it cannot solve.

Author

Assistant Professor, Department of International Relations, Faculty of Security and Strategic Studies, Bangladesh University of Professionals