16 December, 2024 - Author: Daniel Randall

No-one committed to the cause of human freedom should lament the fall of the fascistic regime of Bashar Al-Assad, even if hopes for what comes next must be tempered with concern about the political project of the forces that toppled him.

Paul Mason, in his recent article on Syria, is right to criticise pro-Assad social media influencers like “Partisan Girl” and Richard Medhurst. He is wrong to blame “Leninism” for their politics. Moreover, his criticisms of the left, for abandoning a focus on working-class agency and for campism in general, ring hollow, given his own historic arguments against the primacy of working-class agency, and the fact his own international politics are themselves a form of campism.

Richard Medhurst and “Partisan Girl”, the latter of whom collaborates with neo-Nazis and supports the explicitly fascist Syrian Social Nationalist Party, are somewhat low-hanging fruit. Whilst their boosting by would-be leftists on social media can be seen as part of a wider “Red-Brown” trend, the “Red” element in Medhurst’s politics is marginal, and entirely invisible in “Partisan Girl”’s. But there is undoubtedly a strong campist current within the real-world (i.e., not just social-media) far left too — see, for example, the Communist Party of Britain’s Morning Star responding to Assad’s downfall by lamenting it as “part of imperialism’s region-wide plan”.

Where does that campism originate? Mason says the problem is “Leninism”, because, he argues, Leninism dismisses working-class agency. Because, according to Lenin-according-to-Mason, workers will only ever attain “trade union”, rather than revolutionary, consciousness, the revolutionary project requires a locum to substitute for the working class as the agent of change, either the Leninist party or, in an “anti-imperialist” context, any force whatsoever that militarily opposes hegemonic, i.e., western, imperialism. Mason claims this form of anti-imperialism was “spelled out in black in white” in the minutes of the Second Congress of the Comintern.

It’s hard to know where to start to unpick this knot of distortions and outright fabrications.

Some in Workers’ Liberty, including myself, would not choose “Leninism” as a single-word descriptor for our politics. Political labels associated with the names of individuals have the inbuilt problem of implying a biblicist reverence for that individual’s thought. Some such terms, including “Marxism” and “Trotskyism”, began as terms of abuse, invented by opponents of the ideas they were used to slander, and were only adopted “positively” when enough of those to whom the labels were applied concluded battles over nomenclature were a distraction.

“Leninism” was substantially a construction of Grigory Zinoviev, begun in a period when Lenin himself was mostly out of political activity due to ill health, and continued after Lenin’s death. It is from Zinoviev’s “Leninism”, rather than the Bolshevik party as it actually was in the preceding years, that the model of a “Leninist” party as a highly centralised, monolithic body in which dutiful foot soldiers carry out leaders’ edicts derives. The word “Leninism” is also especially tainted by its confiscation into the term “Marxism-Leninism”, the label used by Stalinism for the political philosophy of its totalitarian cult.

Workers’ Liberty sees itself as part of a revolutionary socialist political tradition of which the pre-Stalinist Bolshevik party was one of the highest historic expressions. We see the Bolshevik-led government in Russia, from 1917 to the early 1920s, as a genuine experiment in working-class rule. The nightmare that came after, under Stalin and his successors, was neither the inevitable outgrowth of that period, nor its legitimate inheritor, but a counter-revolution which overthrew it, and then became the model for “communist” states elsewhere.

When Mason attacks “Leninism”, he does not mean the “Leninism” constructed by Zinoviev, and later by Stalin. He means the entire history of the Bolshevik party. He thereby colludes in the Stalinists’ claims to be the inheritors of 1917. He sees an unbroken, teleologically-impelled continuum from fragments of Lenin’s writing, which he misquotes or quotes out of context, to the Russian Revolution and the Bolshevik-led government, going right through to political trends which predominate on the contemporary far left.

Lenin’s argument about “trade union consciousness”, made in his 1902 pamphlet What Is To Be Done?, was a historical one, remarking on how revolutionary socialist ideas developed. The pamphlet was written at a time when the revolutionary socialist movement, as a distinct, organised political current, had existed for barely 50 years. The actual quote is:

“The history of all countries shows that the working class, exclusively by its own effort, is able to develop only trade union consciousness, i.e., the conviction that it is necessary to combine in unions, fight the employers, and strive to compel the government to pass necessary labour legislation, etc. The theory of socialism, however, grew out of the philosophic, historical, and economic theories elaborated by educated representatives of the propertied classes, by intellectuals.”

Lenin argues that it was via the interaction of theoretical efforts, by people from outside the working class, with the “spontaneous” consciousness, and direct experiences, of workers that revolutionary consciousness developed. Lenin also wrote, in 1894, that, “The role of the ‘intelligentsia’ is to make special leaders from among the intelligentsia unnecessary”. In other words, in developing revolutionary consciousness, the working class can produce its own leadership. This is not the argument of someone who “doesn’t believe in working-class agency”, as Mason claims.

The Bolshevik party of October 1917 was a mass party, with 200,000 members, overwhelmingly working-class. Like all revolutionary socialists historically, including class-struggle anarchists, the Bolsheviks recognised that, as consciousness develops unevenly, the section of the working class prepared to strive directly for revolutionary aims begins as a minority. Through democratic political organisation, including via a revolutionary party, that minority can seek to expand, by conducting agitation and education within the wider working class around itself. The Bolsheviks’ immediate model and reference point was the Social Democratic Party in Germany, an even larger revolutionary workers’ party, with a substantial social, cultural, and educational infrastructure, striving for working-class power.

It is risible to ascribe to Lenin and the Bolsheviks, as Mason does, the belief that “the Western working class [was] incapable of anti-capitalist revolution”. This is a direct inversion of what they believed. Lenin, Trotsky, and other Bolshevik leaders were adamant that the experiment in workers’ rule in Russia could only survive if workers took power in advanced capitalist countries where, unlike in Russia, the working class was not a minority relative to a peasantry. As Lenin put it in 1918: “Without a revolution in Germany, we shall perish.”

They pinned their hopes for the future of socialism on the ability of “the Western working class” to make a revolution. In 1922, Lenin reminded his comrades of a “bitter” but “elementary truth of Marxism”: that “the joint efforts of the workers of several advanced countries [my emphasis - DR] are needed for the victory of socialism.”

(Describing some countries, like Germany, France, Britain, and the USA as “advanced”, and others, like their own country, Russia, as “backwards”, was an analysis of their conditions of economic development, and especially of the development of their working classes, rather than a value judgement.)

Mason, who was once a member of the Workers Power group, must have known these basic facts at some point in his political life. Charitably, one might allow that he has forgotten them. Less charitably, one might infer that he is pretending not to know them in order to traduce a political project by attributing to it positions opposite to the ones it actually held.

The Bolsheviks never saw any social force other than the working class as the agency capable of overthrowing capitalism and replacing it with socialism. The same cannot be said of Paul Mason. He spent the late 2010s promoting a post-class leftism, arguing that: “Networked technology, combined with high levels of education and personal freedom have created a new historical subject across most countries and cultures which will supplant the industrial working class in the progressive project.” I critiqued his views at the time, arguing that working-class agency remained fundamental for any emancipatory politics.

If Mason has now revised his view, and again believes in a central role for specifically working-class agency in the project of anti-capitalist social transformation, that is welcome. But some accounting for his previous departure from that view is surely necessary.

Mason posits the “large available tradition of critical, humanist, democratic socialism that had labelled itself ‘Western Marxism’” as the alternative to “Leninism”. Many of the thinkers and currents sometimes thought of as part of “Western Marxism” can be learnt from. And for sure, the left should be more consistently democratic and should reconnect with humanism, without which the revolutionary project lacks a philosophical-ethical anchoring. But “Western Marxism” is not a sufficiently coherent tradition to offer, nor did most of those associated with it set out to forge, a distinct alternative to pre-Stalinist revolutionary social democracy. And some key figures in the ”Western Marxist” tradition (if such it is, rather a loose grouping of disparate thinkers), such as György Lukács, were, politically, Stalinists, whatever their philosophical heterodoxy.

Mason also ascribes to Lenin and the Bolsheviks the view that “everything anti-colonialist is de facto anti-capitalist”. Again, this is 180-degrees wrong. The very document Mason links to, Lenin’s “Draft Theses on National and Colonial Questions” from June 1920, says the opposite of what Mason claims it says.

According to Mason, this document is the blueprint for contemporary left apologism for Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Iranian state, on the grounds that they are “anti-imperialist”, and therefore necessarily progressive. In fact, Lenin stressed “the need to combat Pan-Islamism and similar trends, which strive to combine the liberation movement against European and American imperialism with an attempt to strengthen the positions of the khans, landowners, mullahs, etc.”

The idea that a force could become progressive solely by dint of what it opposes, regardless of its own subjective political content, was anathema to the founders of the revolutionary socialist tradition, who devoted an entire chapter in The Communist Manifesto to critiquing “Reactionary Socialisms”, currents which opposed capitalism in the name of a worse alternative. Lenin recognised that, like capitalist exploitation, imperial and colonial domination could also be opposed in the name of reactionary alternatives, by local ruling-class forces seeking to assert their own class rule and ideological project. In 1916, he had written:

“No Marxist will forget, however, that capitalism is progressive compared with feudalism, and that imperialism is progressive compared with pre-monopoly capitalism. Hence, it is not every struggle against imperialism that we should support. We will not support a struggle of the reactionary classes against imperialism; we will not support an uprising of the reactionary classes against imperialism and capitalism.”

Elsewhere, Lenin wrote that socialist anti-colonialism must “fight against the privileges and violence of the oppressor nation” but “not in any way condone strivings for privileges on the part of the oppressed nation”. This could be a direct rejoinder to contemporary campists who, rather than supporting struggles for equal rights between Jews and Palestinians, vicariously adopt Islamist or Arab-nationalist hostility to the entire Jewish presence in historic Palestine, seeing all Israelis as “settlers” and peddling fantasies about expelling them en masse.

The problem with the campist left, therefore, is not that its anti-imperialism is too “Leninist”, if one insists on that word, but that it is not “Leninist” enough.

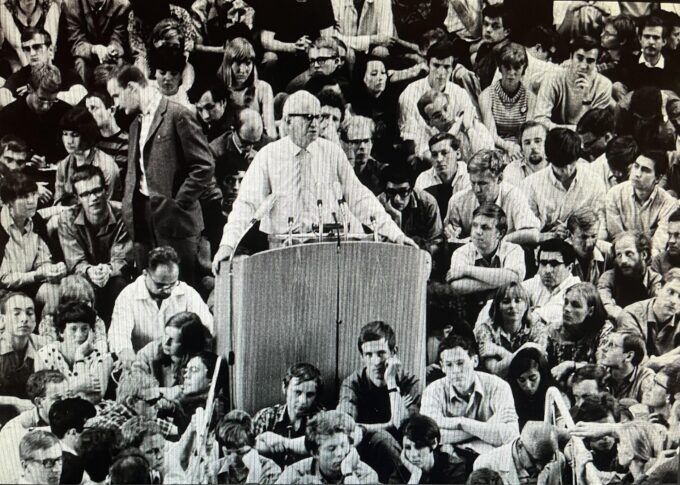

Campism derives not from “Leninism”, but from Stalinism. It was summed up most clearly in the speech given by Poltiburo member Andrei Zhdanov at the founding conference of the Cominform, the Stalinist “international” that succeeded the Third International (Comintern), in 1947.

Zhdanov said: “A new alignment of political forces has arisen […] the division of the political forces operating in the international arena into two major camps: the imperialist and anti-democratic camp, on the one hand, and the anti-imperialist and democratic camp, on the other.”

It fell to the official “Communist” parties in labour and socialist movements throughout the west to argue that the states which comprised the second camp were what Zhdanov claimed they were, and not what they were in reality: hyper-oppressive tyrannies.

The anti-Stalinist socialists who resisted campism most sharply and consistently were the heterodox Trotskyists, primarily based in the USA, who declared they were for “Neither Washington nor Moscow, but international socialism”, insisting on the need for the global working class to constitute itself as an independent social and political force, a “Third Camp” against exploiters and imperialists east and west.

A third camp perspective today means seeking solidarity with struggles of democratic, and especially working-class, forces which oppose all exploiters and oppressors, global and local. The old slogan might be reformulated as: “Neither Washington nor Moscow nor Riyadh nor Beijing nor Tehran, but international socialism.” Not as usable for a newspaper masthead, perhaps, but conveying the contemporary expression of the same idea.

But the agency Paul Mason looks to today is not an independent of the working class, but “the rules-based global order”, the institutions of which he specifies as “Britain and France, the UN, EU, NATO member Turkey, the despised state of Israel plus old Joe Biden in America.” Whatever one thinks of the idea of a “rules-based global order“ (whose “rules“, one might ask?), Kurds and Palestinians, and indeed Turkish and Israeli democrats and internationalists, might well raise an eyebrow about the likelihood of the current regimes of Turkey and Israel contributing constructively to its enforcement. And if Mason wants to promote a “critical, humanist, democratic socialism“ that emphasises “working-class agency“, how does he square that with preaching trust and confidence in states and institutions that are all projections of capitalist class power?

Evidently, there are no third camp forces active in Syria capable of contending for hegemony. Mason is right that we have to “start from where we are”. But starting from where we are in order to go where? When it comes to practical politics, Mason’s insistence on the primacy of “working-class agency” seems to disappear, and the maximum extent of his political horizon is bolstering one bloc of imperialist powers, the one led by the US, against the bloc comprising Chinese, Russian, and Iranian imperialism. What is this if not campism?

An internationalist perspective for the Middle East that takes working-class agency as its starting point does not preach confidence in the machinations of NATO powers. Instead, it emphasises the central role of the working classes of all nations in the region — Arab, Kurdish, Persian, Jewish, and others. It stresses the need for workers’ movements to pursue political struggles for consistent democracy and equal rights, including national rights. Equality of national rights — that is, an equal right of all peoples to self-determination — is the only possible democratic answer to the chauvinism and counter-chauvinism implied by both forms of campism. Perhaps especially, working-class internationalism must focus on the enormous potential transformative power of the Iranian working class, and dedicate activist energies to amplifying and supporting its struggles.

I’m sure Paul Mason is interested in that, on some level. But you wouldn’t know it from what he has written recently. In practical terms, he has mostly reduced himself to an unpaid adviser to the British state on military and security strategy. He is entitled to pursue his course, but if that is the one he chooses, he should leave the critique of campism to those of us who oppose it consistently, and advocacy of working-class agency to those of us who still actually believe in it.