Mali's Military

Mark Fischer/Flickr

A view of Bamako, Mali with the Niger River in the background.

28 DECEMBER 2021

Voice of America (Washington, DC)

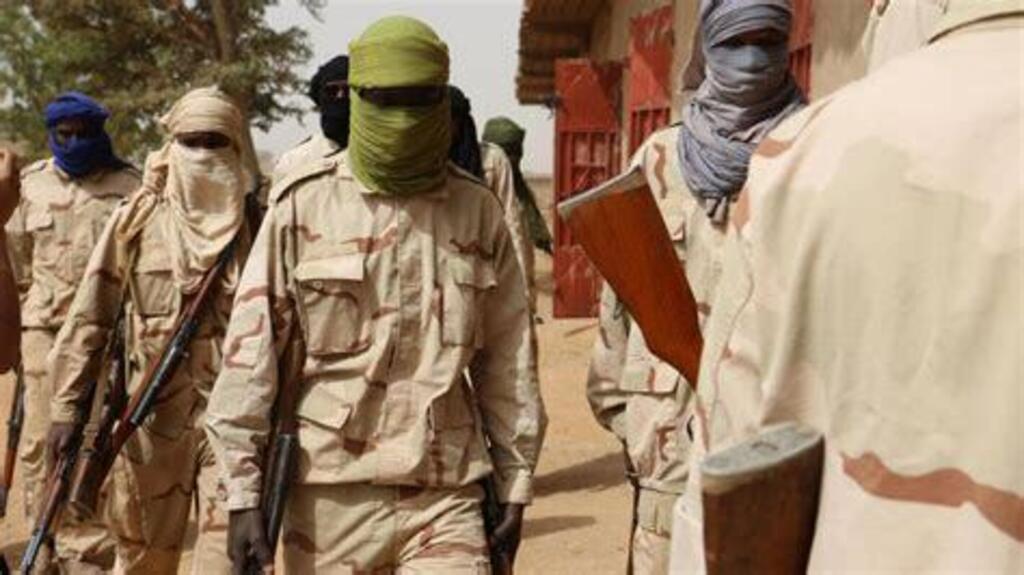

Bamako — Mali's military government has denied hiring Russian mercenaries from the controversial Wagner Group, which has been sanctioned by the European Union for rights abuses. France and 15 other Western nations last week condemned what they said was Russia's deployment of Wagner fighters to Mali. Mali's transitional government says it is only engaged with official Russian military trainers. Analysts weigh in on Russia's military involvement in Mali as French troops are drawing down.

Mali's transitional government this month denied what it called "baseless allegations" that it hired the controversial Russian security firm the Wagner Group to help fight Islamist insurgents.

Western governments and U.N. experts have accused Wagner of rights abuses, including killing civilians, in the Central African Republic and Libya.

The response came Friday after Western nations made the accusations, which Mali's military government dismissed with a demand that they provide independent evidence.

A day earlier, France and 15 other Western nations had condemned what they called the deployment of Wagner mercenaries to Mali.

The joint statement said they deeply regret the transitional authorities' choice to use already scarce public funds to pay foreign mercenaries instead of supporting its own armed forces and the Malian people.

The statement also called on the Russian government to behave more responsibly, accusing it of providing material support to the Wagner Group's deployment, which Moscow denies.

The Mali government acknowledged what it called "Russian trainers" were in the country. It said they were present to help strengthen the operational capacities of their defense and security forces.

Aly Tounkara is director of the Center for Security and Strategic Studies in the Sahel, a Bamako-based think tank.

He says it's hard to tell if the Russian security presence is military or mercenary but, regardless, would likely be supporting rather than front-line fighting.

This could allow the Malian army to have victories over the enemy that will be attributed to them, says Tounkara, which was not the case with the French forces. He says the second advantage is that victories over extremists could allow Mali's military to legitimize itself. We must remember, says Tounkara, that one of the reasons for the forced departure of President Keita, was that the security situation was so bad.

Mali's President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita was overthrown in an August 2020 coup led by Colonel Assimi Goita after months of anti-government protests, much of it over worsening security.

Goita launched a second coup in May that removed the interim government leaders, but has promised to hold elections in 2022.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has been pushing Mali's military government to hold elections.

ECOWAS in November expressed concern over a potential Wagner Group deployment to Mali after unconfirmed reports that the military government was in talks with the mercenary group.

Popular protests in Bamako have called for French forces to leave Mali and last year some protesters were seen calling for Russian ones to intervene.

Since French forces first arrived in Mali in 2013, public opinion on their presence has shifted from favorable to widely negative.

The French military has been gradually drawing down its anti-insurgent Operation Barkhane forces from the Sahel region.

French forces this year withdrew from all but one military base in northern Mali, saying the Malian armed forces were ready to take the lead on their own security.

But analysts say one consequence of the French leaving is that the Malian army is seeking other partners.

Boubacar Salif Traore is director of Afriglob Conseil, a Bamako-based development and security consulting firm.

"Official Russian cooperation would be very advantageous for the Malian army in terms of supplying equipment," he says. "Mali, and many African countries, notably the Central African Republic, have concluded that France does not play fair in terms of delivering arms. Every time these states ask for weapons, either there's an embargo or there is a problem in procuring these weapons. Russia can provide these weapons without constraints and it's precisely that which interests Mali."

In September, Mali received four military helicopters and other weapons bought from Russia.

The Malian transitional government's statement Friday did not elaborate on what the Russian trainers would be doing in Mali.

When asked to comment, a government spokesman would not elaborate and referred questions to the ministry of foreign affairs, which does not list any contact numbers on its website.