Kathryn Crawford, Assistant Professor of Environmental Health, Middlebury

Tue, March 7, 2023

PFAS, often used in water-resistant gear, also find their way into drinking water and human bodies. CasarsaGuru via Getty Images

You’ve probably been hearing the term PFAS in the news lately as states and the U.S. government consider rules and guidelines for managing these “forever chemicals.”

Even if the term is new to you, chances are good that you’re familiar with what PFAS do. That’s because they’re found in everything from nonstick cookware to carpets to ski wax.

PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, which are a large group of human-made chemicals – currently estimated to be around 9,000 individual chemical compounds – that are used widely in consumer products and industry. They can make products resistant to water, grease and stains and protect against fire.

Waterproof outdoor apparel and cosmetics, stain-resistant upholstery and carpets, food packaging that is designed to prevent liquid or grease from leaking through, and certain firefighting equipment often contain PFAS. In fact, one recent study found that most products labeled stain- or water-resistant contained PFAS, and another study found that this is even true among products labeled as “nontoxic” or “green.” PFAS are also found in unexpected places like high-performance ski and snowboard waxes, floor waxes and medical devices.

At first glance, PFAS sound pretty useful, so you might be wondering “what’s the big deal?”

The short answer is that PFAS are harmful to human health and the environment.

Some of the very same chemical properties that make PFAS attractive in products also mean these chemicals will persist in the environment for generations. Because of the widespread use of PFAS, these chemicals are now present in water, soil and living organisms and can be found across almost every part of the planet, including Arctic glaciers, marine mammals, remote communities living on subsistence diets, and in 98% of the American public.

The Environmental Protection Agency recently issued new warnings about their risk in drinking water even at very low levels.

Health risks from PFAS exposure

Once people are exposed to PFAS, the chemicals remain in their bodies for a long time – months to years, depending on the specific compound – and they can accumulate over time.

Research consistently demonstrates that PFAS are associated with a variety of adverse health effects. A recent review by a panel of experts looking at research on PFAS toxicity concluded with a high degree of certainty that PFAS contribute to thyroid disease, elevated cholesterol, liver damage and kidney and testicular cancer.

Stain-resistant fabrics and carpets often contain PFAS. Deagreez via Getty Images

Further, they concluded with a high degree of certainty that PFAS also affect babies exposed in utero by increasing their likelihood of being born at a lower birth weight and responding less effectively to vaccines, while impairing women’s mammary gland development, which may adversely impact a mom’s ability to breastfeed.

The review also found evidence that PFAS may contribute to a number of other disorders, though further research is needed to confirm existing findings: inflammatory bowel disease, reduced fertility, breast cancer and an increased likelihood of miscarriage and developing high blood pressure and preeclampsia during pregnancy. Additionally, current research suggests that babies exposed prenatally are at higher risk of experiencing obesity, early-onset puberty and reduced fertility later in life.

Collectively, this is a formidable list of diseases and disorders.

Who’s regulating PFAS?

PFAS chemicals have been around since the late 1930s, when a DuPont scientist created one by accident during a lab experiment. DuPont called it Teflon, which eventually became a household name for its use on nonstick pans.

Decades later, in 1998, Scotchgard maker 3M notified the Environmental Protection Agency that a PFAS chemical was showing up in human blood samples. At the time, 3M said low levels of the manufactured chemical had been detected in people’s blood as early as the 1970s.

Despite the lengthy list of serious health risks linked to PFAS and a tremendous amount of federal investment in PFAS-related research in recent years, PFAS haven’t been regulated at the federal level in the United States.

The EPA has issued advisories and health-based guidelines for two PFAS compounds – PFOA and PFOS – in drinking water, though these guidelines are not legally enforceable standards. And the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry has a toxicological profile for PFAS.

Federal rules could be coming. Congress is considering legislation to ban PFAS in some food packaging. The EPA has a road map for PFAS regulations it is considering, including regulations involving drinking water. The Biden administration has said it also expects to list PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under the Superfund law, a move that worries utilities and businesses that use PFAS-containing products or processes because of the expense of cleanup.

States, meanwhile, have been taking their own actions to protect residents against the risk of PFAS exposure.

At least 23 states have laws targeting PFAS in various uses, such as in food packaging and carpets. But relying on state laws places burdens on state agencies responsible for enforcing them and creates a patchwork of regulations which, in turn, place burdens on business and consumers to navigate regulatory nuances across state lines.

So, what can you do about PFAS?

Based on current scientific understanding, most people are exposed to PFAS primarily through their diet, though drinking water and airborne exposures may be significant among some people, especially if they live near known PFAS-related industries or contamination.

The best ways to protect yourself and your family from risks associated with PFAS are to educate yourself about potential sources of exposures.

Products labeled as water- or stain-resistant have a good chance of containing PFAS. Check the ingredients on products you buy and watch for chemical names containing “fluor-.” Specific trade names, such as Teflon and Gore-Tex, are also likely to contain PFAS.

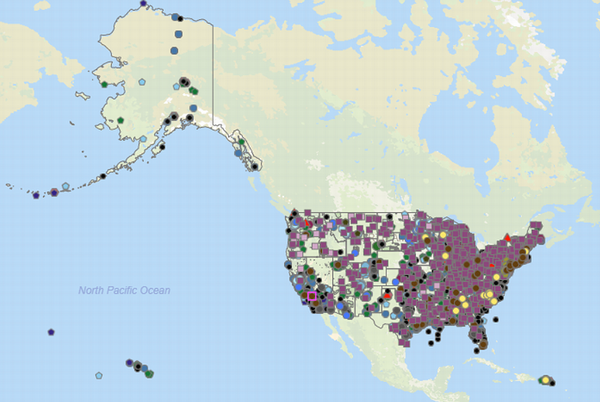

Check whether there are sources of contamination near you, such as in drinking water or PFAS-related industries in the area. Some states don’t test or report PFAS contamination, so the absence of readily available information does not necessarily mean the region is free of PFAS problems.

For additional information about PFAS, check out the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, EPA and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention websites or contact your state or local public health department.

If you believe you have been exposed to PFAS and are concerned about your health, contact your health care provider. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry has a succinct report to help health care professionals understand the clinical implications of PFAS exposure.

This article was updated July 8, 2022, with new legislation signed in Rhode Island and Hawaii.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts.

It was written by: Kathryn Crawford, Middlebury.

Read more:

PFAS are showing up in children’s stain- and water-resistant products – including those labeled ‘nontoxic’ and ‘green’

PFAS ‘forever chemicals’ are widespread and threaten human health – here’s a strategy for protecting the public

Restoring the Great Lakes: After 50 years of US-Canada joint efforts, some success and lots of unfinished business

Kathryn Crawford has received funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Regulating 'forever chemicals': 3 essential reads on PFAS

The Conversation

Tue, March 7, 2023

A new federal regulation will set national limits on two 'forever chemicals' widely found in drinking water. Thanasis Zovoilis/moment via Getty Images

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is preparing to release a draft regulation limiting two fluorinated chemicals, known by the abbreviations PFOA and PFOS, in drinking water. These chemicals are two types of PFAS, a broad class of substances often referred to as “forever chemicals” because they are very persistent in the environment.

PFAS are widely used in hundreds of products, from nonstick cookware coatings to food packaging, stain- and water-resistant clothing and firefighting foams. Studies show that high levels of PFAS exposure may lead to health effects that include reduced immune system function, increased cholesterol levels and elevated risk of kidney or testicular cancer.

Population-based screenings over the past 20 years show that most Americans have been exposed to PFAS and have detectable levels in their blood. The new regulation is designed to protect public health by setting an enforceable maximum standard limiting how much of the two target chemicals can be present in drinking water – one of the main human exposure pathways.

These three articles from The Conversation’s archives explain growing concerns about the health effects of exposure to PFAS and why many experts support national regulation of these chemicals.

1. Ubiquitous and persistent

PFAS are useful in many types of products because they provide resistance to water, grease and stains, and protect against fire. Studies have found that most products labeled stain- or water-resistant contained PFAS – even if those products are labeled as “nontoxic” or “green.”

“Once people are exposed to PFAS, the chemicals remain in their bodies for a long time – months to years, depending on the specific compound – and they can accumulate over time,” wrote Middlebury College environmental health scholar Kathryn Crawford. A 2021 review of PFAS toxicity studies in humans “concluded with a high degree of certainty that PFAS contribute to thyroid disease, elevated cholesterol, liver damage and kidney and testicular cancer.”

The review also found strong evidence that in utero PFAS exposure increases the chances that babies will be born at low birth weights and have reduced immune responses to vaccines. Other possible effects yet to be confirmed include “inflammatory bowel disease, reduced fertility, breast cancer and an increased likelihood of miscarriage and developing high blood pressure and preeclampsia during pregnancy.”

“Collectively, this is a formidable list of diseases and disorders,” Crawford observed.

Read more: What are PFAS, and why is the EPA warning about them in drinking water? An environmental health scientist explains

2. Why national regulations are needed

Under the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Environmental Protection Agency has the authority to set enforceable national regulations for drinking water contaminants. It also can require state, local and tribal governments, which manage drinking water supplies, to monitor public water systems for the presence of contaminants.

Until now, however, the agency has not set binding standards limiting PFAS exposure, although it has issued nonbinding advisory guidelines. In 2009 the agency established a health advisory level for PFOA in drinking water of 400 parts per trillion. In 2016, it lowered this recommendation to 70 parts per trillion, and in 2022 it reduced this threshold to near-zero.

But many scientists have found fault with this approach. EPA’s one-at-a-time approach to assessing potentially harmful chemicals “isn’t working for PFAS, given the sheer number of them and the fact that manufacturers commonly replace toxic substances with ‘regrettable substitutes – similar, lesser-known chemicals that also threaten human health and the environment,” wrote North Carolina State University biologist Carol Kwiatkowski.

In 2020 Kwiatkowski and other scientists urged the EPA to manage the entire class of PFAS chemicals as a group, instead of one by one. “We also support an 'essential uses’ approach that would restrict their production and use only to products that are critical for health and proper functioning of society, such as medical devices and safety equipment. And we have recommended developing safer non-PFAS alternatives,” she wrote.

Read more: PFAS 'forever chemicals' are widespread and threaten human health – here's a strategy for protecting the public

Medical assistant Jennifer Martinez draws blood from Joshua Smith in Newburgh, N.Y., Nov. 3, 2016, to test for PFOS levels. PFOS had been used for years in firefighting foam at the nearby military air base, and was found in the city’s drinking water reservoir at levels exceeding federal guidelines. AP Photo/Mike Groll

3. Breaking down PFAS

PFAS chemicals are widely present in water, air, soil and fish around the world. Unlike with some other types of pollutants, there is no natural process that breaks down PFAS once they get into water or soil. Many scientists are working to develop ways of capturing these chemicals from the environment and breaking them down into harmless components.

There are ways to filter PFAS out of water, but that’s just the start. “Once PFAS is captured, then you have to dispose of PFAS-loaded activated carbons, and PFAS still moves around. If you bury contaminated materials in a landfill or elsewhere, PFAS will eventually leach out. That’s why finding ways to destroy it are essential,” wrote Michigan State University chemists A. Daniel Jones and Hui Li.

Incineration is the most common technique, they explained, but that typically requires heating the materials to around 1,500 degrees Celsius (2,730 degrees Fahrenheit), which is expensive and requires special incinerators. Various chemical processes offer alternatives, but the approaches that have been developed so far are hard to scale up. And converting PFAS into toxic byproducts is a significant concern.

“If there’s a lesson to be learned, it’s that we need to think through the full life cycle of products. How long do we really need chemicals to last?” Jones and Li wrote.

Read more: How to destroy a 'forever chemical' – scientists are discovering ways to eliminate PFAS, but this growing global health problem isn't going away soon

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts.

It was written by: Jennifer Weeks, The Conversation.

Read more:

Flood maps show US vastly underestimates contamination risk at old industrial sites

Is your drinking water safe? Here’s how you can find out