Fractured artificial rock helps crack a 54-year-old mystery

Princeton researchers have solved a 54-year-old puzzle about why certain fluids strangely slow down under pressure when flowing through porous materials, such as soils and sedimentary rocks. The findings could help improve many important processes in energy, environmental and industrial sectors, from oil recovery to groundwater remediation.

The fluids in question are called polymer solutions. These solutions—everyday examples of which include cosmetic creams and the mucus in our noses—contain dissolved polymers, or materials made of large molecules with many repeating subunits. Typically, when they're put under pressure, polymer solutions become less viscous and flow faster. But when going through materials with lots of tiny holes and channels, the solutions tend to become more viscous and gunky, reducing their flow rates.

To get at the root of the problem, the Princeton researchers devised an innovative experiment using a see-through porous medium made of tiny glass beads—a transparent artificial rock. This lucid medium allowed the researchers to visualize a polymer solution's movement. The experiment revealed that the long-baffling increase in viscosity in porous media happens because the polymer solution's flow becomes chaotic, much like turbulent air on an airplane ride, swirling into itself and gumming up the works.

"Surprisingly, until now, it has not been possible to predict the viscosity of polymer solutions flowing in porous media," said Sujit Datta, an assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering at Princeton and senior author of the study appearing Nov. 5 in the journal Science Advances. "But in this paper, we've now finally shown these predictions can be made, so we've found an answer to a problem that has eluded researchers for over a half-century."

"With this study, we finally made it possible to see exactly what is happening underground or within other opaque, porous media when polymer solutions are being pumped through," said Christopher Browne, a Ph.D. student in Datta's lab and the paper's lead author.

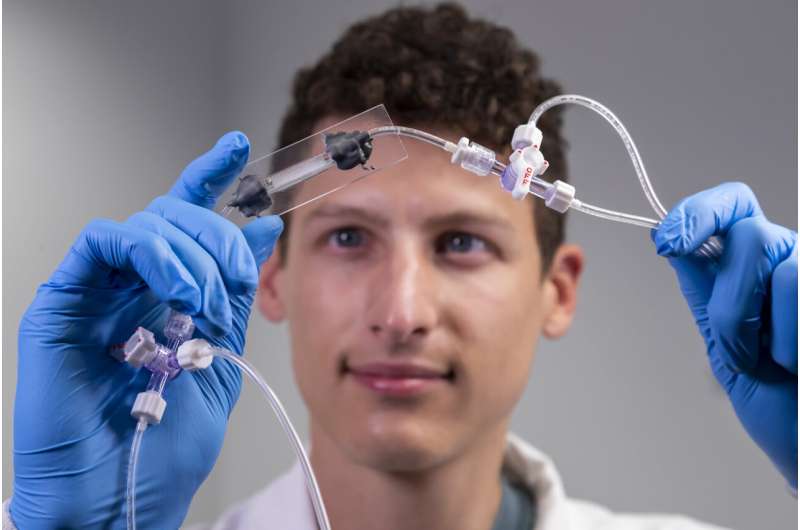

Browne ran the experiments and built the experimental apparatus, a small rectangular chamber randomly packed with tiny borosilicate glass beads. The setup, akin to an artificial sedimentary rock, spanned only about half the length of a pinky finger. Into this faux rock, Browne pumped a common polymer solution laced with fluorescent latex microparticles to help see the solution's flow around the beads. The researchers formulated the polymer solution so the material's refractive index offset light distortion from the beads and made the whole setup transparent when saturated. Datta's lab has innovatively used this technique to create see-through soil for studying ways to counter agricultural droughts, among other investigations.

Browne then zoomed in with a microscope on the pores, or holes between the beads, which occur on the scale of 100 micrometers (millionths of a meter) in size, or similar to the width of a human hair, in order to examine the fluid flow through each pore. As the polymer solution worked its way through the porous medium, the fluid's flow became chaotic, with the fluid crashing back into itself and generating turbulence. What's surprising is that, typically, fluid flows at these speeds and in such tight pores are not turbulent, but "laminar": the fluid moves smoothly and steadily. As the polymers navigated the pore space, however, they stretched out, generating forces that accumulated and generated turbulent flow in different pores. This effect grew more pronounced when pushing the solution through at higher pressures.

"I was able to see and record all these patchy regions of instability, and these regions really impact the transport of the solution through the medium," said Browne.

The Princeton researchers used data gathered from the experiment to formulate a way to predict the behavior of polymer solutions in real-life situations.

Gareth McKinley, a professor of mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who was not involved in the study, offered comments on its significance.

"This study shows definitively that the large increase in the macroscopically observable pressure drop across a porous medium has its microscopic physical origins in viscoelastic flow instabilities that occur on the pore scale of the porous medium," McKinley said.

Given that viscosity is one of the most fundamental descriptors of fluid flow, the findings not only help deepen understanding of polymer solution flows and chaotic flows in general, but also provide quantitative guidelines to inform their applications at large scales in the field.

"The new insights we have generated could help practitioners in diverse settings determine how to formulate the right polymer solution and use the right pressures needed to carry out the task at hand," said Datta. "We're particularly excited about the findings' application in groundwater remediation."

Because polymer solutions are inherently goopy, environmental engineers inject the solutions into the ground at highly contaminated sites such as abandoned chemical factories and industrial plants. The viscous solutions help push out trace contaminants from the affected soils. Polymer solutions likewise aid in oil recovery by pushing oil out of the pores in underground rocks. On the remediation side, polymer solutions enable "pump and treat," a common method for cleaning up groundwater polluted with industrial chemicals and metals that involves bringing the water to a surface treatment station. "All these applications of polymer solutions, and more, such as in separations and manufacturing processes, stand to benefit from our findings," said Datta.

Overall, the new findings on polymer solution flow rates in porous media brought together ideas from multiple fields of scientific inquiry, ultimately disentangling what had started out as a long-frustrating, complex problem.

"This work draws connections between studies of polymer physics, turbulence, and geoscience, following the flow of fluids in rocks underground as well as through aquifers," said Datta. "It's a lot of fun sitting at the interface between all these different disciplines."