In February of 2018, Laurie Brooks, a 51-year-old nurse in Abbotsford, B.C., learned she had colon cancer. Next came radiation, chemotherapy and a surgery that removed an eight-centimetre-long tumour. But at her one-year surgery follow-up, her oncologist found that the cancer had metastasized. She had anywhere between six months and a year to live

Brooks and her husband, Glenn, who runs a home-renovation business, have four kids in their 20s. After the check-up news, she couldn’t sleep and cried constantly. She became withdrawn and felt anger at both the situation and at herself. At times she was gripped by an unshakable feeling that she had personally done something wrong. She feared having to inform her kids, for the second time, that their mother was dying. Soon she found that she couldn’t move her left arm—a psychosomatic side effect of her emotional distress. “I didn’t deal with any of the emotional stuff,” she says. “I just shoved that down inside while I got through the physical challenges of cancer.”

Then a family friend suggested a way she could find a measure of peace and deal with all that emotional stuff: take magic mushrooms.

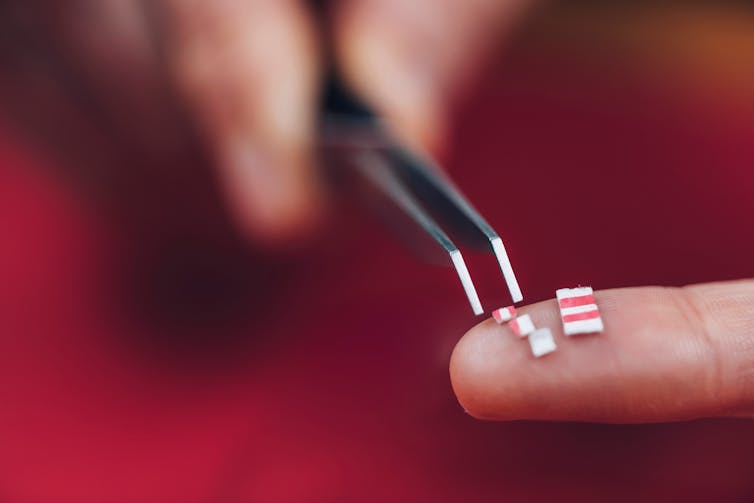

In the last few years, an underground network of Canadian psychotherapists and medical practitioners, inspired by successful clinical trials, has helped patients gain access to psychedelics such as magic mushrooms, the gnarled fungi containing the naturally occurring chemical psilocybin. Many of those patients are terminally ill or are suffering from chronic depression or anxiety. They believe that psychedelics alleviate their suffering and help them get more in touch with their emotions. Psychedelics have been called the new cannabis—at least in Canada.

Brooks contacted a B.C. therapist who has helped other cancer patients experience magic-mushroom trips. Although she had never dabbled in mind-expanding drugs before, and was nervous, she wanted to spend what may be her final months living “authentically,” finding the self that was so often lost in her identification as a wife and mother and cancer patient.

Lying in a comfy bed and flanked by the therapist and a close friend, Laurie took three grams of magic mushrooms—a high dose guaranteed to send her on a trip. She’d prepared a mantra to guide her through the psychedelic experience. “Trust, be open and let go,” she told herself.

Before long, her mind opened into a realm of kaleidoscopic colours that she first found entertaining and then just a bit annoying. She next found herself pitched into a cold darkness. As she wrote in the notes she compiled post-trip, “It was like I was floating around in space but there weren’t any stars. It was just pitch black.”

At one point during her trip, while her hallucinations were peaking, Laurie visualized herself as a prisoner. “I saw myself in jail, with shackles on my wrists, and the shackles fell off, and the jail door slid open.” Brooks was free.

As the hallucinations subsided and she settled back into our shared, everyday reality, she realized she could move her left arm again. She swung it in wide circles.

In the recreational culture of psychedelics, users often talk about the “afterglow.” It’s a feeling of clarity or emotional well-being that persists after the drugs themselves have worn off. It’s like the opposite of a hangover. The sun seems warmer. You notice dew on each blade of grass glistening anew. Many patients only need to experience a magic-mushroom trip once to feel like the treatment was a success.

A year after her trip, Brooks was still glowing. “Everybody looks at me and says, ‘You don’t look sick at all!’” she reflects. “I don’t have all the fear and anxiety anymore.”

A long and controversial history

Before psychedelics like magic mushrooms gained notoriety in the 1960s as the preferred drugs of the Woodstock generation, ancient and Indigenous cultures prized them for millennia for the experiences they produced. Psychedelics induced states of consciousness with deep mystical and spiritual dimensions.

So-called “classical psychedelics”—a category that includes psilocybin, LSD, mescaline and a few configurations of dimethyltryptamine, or DMT—are psychologically powerful and spiritually potent. At the same time, they pose no real risk of addiction. Medical researchers believe that these drugs function by affecting the serotonin, a neurotransmitter that affects everything from mood to memory. The ceremonial and prehistorical use of these compounds has much to do with them being readily available in nature. That includes the bulbous and prickly peyote cactus, to DMT-containing “pink carpet” perennials native to South Africa, to the formidable Psilocybe azurescens mushrooms that peek up from the fertile soil of Oregon’s Columbia River Delta. LSD, meanwhile, is a chemical derivative of ergot, itself a fungal growth common on rye plants.

Scientists are now reassessing psychedelics as a promising therapeutic. In 2006, a team at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University led by neuropharmacologist Roland Griffiths demonstrated that psilocybin stimulated spiritual and deeply emotional experiences (comparable to the birth of a child or the death of a parent) in 30 volunteers. The resulting paper gave scientific heft to what generations of recreational users already knew: that psychedelics could facilitate profound (or “mystical-type”) experiences and lead to a shift in a user’s perception of themselves and their place in the world.

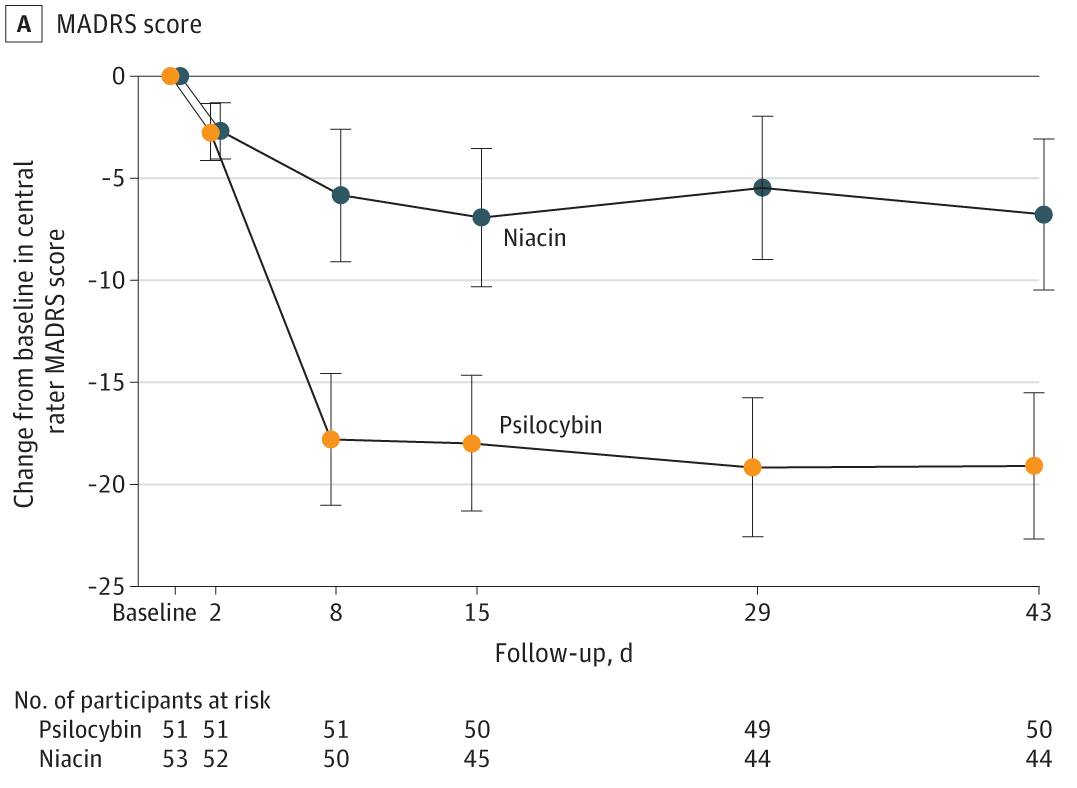

The therapeutic potential of such a revelation seemed limitless. Subsequent Hopkins research revealed that psilocybin could produce “substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer.”

This research spurred a psychedelic renaissance: a period of renewed clinical and recreational interest in these compounds. Writer Michael Pollan, prompted both by the Hopkins research and a nagging sense of emptiness in his own life, experimented with a range of psychedelics, which he wrote about in his 2018 bestseller How to Change Your Mind.

In the first episode of her Netflix series The Goop Lab, actor and wellness guru Gwyneth Paltrow dispatched her staff to a magic-mushroom ceremony at a Jamaican beach resort. And in late 2019, Canadian businessman Kevin O’Leary announced his investment in MindMed, a start-up using psychedelics to treat addiction. It’s one of several Canadian businesses trying to capitalize on the hype.

Therapy and bad trips

Canada has long played a central role in psychedelics research. The field of psychedelic therapy was pioneered at Weyburn Mental Hospital in the 1950s, under Dr. Humphry Osmond and Dr. Abram Hoffer. It was Osmond who, in a correspondence with novelist and mind-expansion aficionado Aldous Huxley, coined the word psychedelic, meaning, roughly, “mind-manifesting.”

In their earliest medical applications, psychedelics like psilocybin and LSD were used to induce states of temporary psychosis—in order to observe and understand those states.

These applications were not always well-intentioned, or even consensual. In the 1950s and ’60s, Montreal’s Allan Memorial Institute was the site of countless psychedelic trials that were overseen by Scottish psychiatrist Ewen Cameron, funded by the CIA and partially underwritten by the Canadian government as a means of exploring the potential of mind control.

In one case, the wife of a Manitoba MP sought Cameron’s help in treating postpartum depression, only to be unwittingly dosed with LSD and subjected to brainwashing tapes. (A group of these victims sued the CIA in the 1980s and won.)

Osmond and Hoffer’s work led to the idea that these potent hallucinogens could also be powerful therapeutic tools. Clinicians analyzed the effects of psychedelic drugs in treating everything from alcoholism to schizophrenia and arrived at a crucial conclusion: that a positive psychedelic experience, one that facilitated a profound and lasting change in the patient, relied significantly on a positive mental outlook and an encouraging environment. Treat patients like they’re mad and they’ll behave accordingly. Treat them like they’re sick, in need of healing, and that healing is more likely to occur.

Much of the ’60s-era panic around these substances centred on “bad trips,” in which a powerful drug produced a state of mental frenzy resembling psychosis. In one famous 1969 case, Saskatchewan-born radio host Art Linkletter’s 20-year-old daughter, Diane, jumped out a window—a death her dad attributed to LSD.

The association of psychedelics with the ’60s counterculture had a blowback effect on serious-minded clinical research. Erika Dyck, Canada Research Chair in the History of Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan, notes in her book Psychedelic Psychiatry how, as mind expansion moved from the clinic to the campus, “Medical authorities promoting psychedelic psychiatry were perceived as indirectly endorsing a cultural revolution.”

The doctor who believes magic mushrooms can help

More than anyone, Dr. Bruce Tobin is responsible for legitimizing psychedelics therapy in Canada today. He’s worked as a private psychotherapist for the last 35 years and is a former professor of child and youth care at the University of Victoria. He’s 73 years old, lanky and friendly, with a white beard and a wide smile framed by a messy mop of hair.

© Photo: Nik West Psychotherapist Bruce Tobin is leading experiments with psychedelic therapy in Canada.

Tobin was drawn to the field by the results of studies and clinical trials, especially those at Johns Hopkins. He struck up an informal alliance—a friendship, really—with some of the top researchers at the university. In January 2017, he filed a class-action exemption application with Health Canada for access to psilocybin for people who met specific criteria, in order to provide therapeutic treatments. He founded TheraPsil—a non-profit with five employees—in the fall of 2019 while waiting for that application’s results.

After that first application was denied, Tobin and his staff focused on bulking up scientific, evidence-based arguments for psilocybin. Then, they reapplied with individual applications focused on granting compassionate access to specific patients suffering from intractable end-of-life anxiety. Tobin was ready to take the case to the Supreme Court, and failing that, practise a little civil disobedience himself by joining the ranks of on-the-sly psychedelic therapists.

Then, to his surprise, the government approved the first batch of his patient applications last August. “My sense is that, initially, Health Canada hoped that by more or less ignoring my application, I’d go away,” Tobin says, speaking from his home just north of Victoria, in North Saanich. “I’m not going away.”

Tobin’s mission is personal. In his career, he’s watched as various pharmaceutical cure-alls passed in and out of fashion. He also saw his own mother struggle with depression and anxiety—pharmaceuticals only numbed or exacerbated the root causes of her pain. He calls psilocybin an “existential threat” to Big Pharma and daily regimens of prescription drugs. The treatment is safe, relatively inexpensive (versus a lifetime of pricey prescription drug renewals), the outcomes are better, and, in many cases, it need only be undertaken once. New studies from Johns Hopkins show that patients who took the treatment four years ago are still reporting the positive effects—the benefits of a long, long afterglow.

Tobin recommends psilocybin should only be taken after establishing a rapport between the patient and the therapist. “This isn’t an easy process, where you simply take a pill and the heavens open and you’ll have transcendent, mystical experiences,” he says. “In many sessions there is difficult emotional work to be done.”

Like any therapy, these sessions hinge on confronting repressed, buried or otherwise uncomfortable feelings. The hallucinations, in many cases, function as metaphorical mini-movies. Imagine being confronted by some terrifying monster, then defeating it. Or think of Laurie Brooks busting herself out of the prison of her own inhibitions.

While fanciful and conjured in the mind, such experiences feel deeply real to the patient. And with proper therapeutic guidance (often termed “integration”), these profound lessons can be carried over into waking life when the drug’s effect subsides.

The power of the experience is further attributed to its ability to stir these feelings in a relatively compact session. Psychedelic enthusiasts describe the experience as being like years of therapy condensed into six or eight hours. Tobin is quick to dismiss such hyperbole, but he admits there is a measure of truth in such proclamations. “The effect of the medicine,” he explains, “makes it such that a person is able to process a lot more material than is normally accessible to them in any ordinary state of consciousness.”

The exemptions granted by Health Canada allow select patients to possess and consume psilocybin. As with cannabis—which began its route to medical decriminalization and, eventually, legality, with a similar exemption—these end-of-life therapy applications are the thin end of the wedge.

Other research companies in Canada are already squeezing through the door Tobin cracked open, seeking exemptions to study the effects of psychedelics in treating everything from obesity to cluster headaches to treatment-resistant depression. Health Canada has recently granted further exemptions to clinical researchers and biotechnology companies, plus 17 licences to psilocybin producers that supply clinics and researchers. Therapists are also seeking exemptions to take the drug in their training, in order to gain a more robust understanding of the psychedelic experience they hope to one day administer.

“The science is swiftly moving,” says Tobin. “The therapeutic merits of psilocybin don’t just pertain to end-of-life issues.”

Tobin believes his scientific credibility helped his application in the eyes of the government. And it’s the continued provability of psilocybin’s benefits that seems likely to shape its expanded legal framework. For now, however, psychedelics are primarily used for one noble end: easing the fear of death in people with terminal diagnoses.

Making the last days better

On August 12, 2020, in Saskatoon, about a four-hour drive from the now-demolished Weyburn Mental Hospital, Thomas Hartle became the first Canadian since 1974 to legally consume magic mushrooms.

Hartle, a 52 year-old father of two who works as an IT technician, was diagnosed with stage four colon cancer in 2016. Treatments put the cancer in remission for a couple years, but it returned in the summer of 2019, along with emotional distress, anxiety and crippling panic attacks.

The chemotherapy also led to neuropathy, a form of nerve damage that can cause numbness and weakness in the extremities. Researching Hericium erinaceus, a stringy mushroom used in some Eastern medicine practices to treat nerve damage, Hartle stumbled across the Johns Hopkins research on psilocybin and end-of-life distress. His interest was piqued, though he remained a little incredulous. “My experience with psychedelics was strictly through books and the media,” he explains. “To me, psychedelics were a party drug that people used in the ’60s.”

Hartle’s exploratory googling also led him to TheraPsil. Last spring, he reached out, and they added him to their exemption applications. After a few lengthy phone calls and some introductory screening, Tobin flew to Saskatoon to spend some time with Hartle and his family and build the sort of trusting relationship that is integral to the success of any therapeutic process. While Hartle tripped behind an eye mask, safely ensconced in his bed and listening to calming music, Tobin kept watch, making sure everything was going smoothly and offering words of encouragement.

“Less is kind of more,” Tobin explains. “We don’t want to put ourselves into the picture. The more invisible I become, the better, so the patient can focus exclusively on their inner experience.”

I spoke to Hartle a few weeks after the trip, and just a day after he began a new round of chemotherapy. He remained irrepressibly chipper. Before Hartle’s psilocybin trip, Tobin administered a Hamilton assessment—a scale that rates anxiety. A score of 25 to 30 would mean moderate to severe anxiety. Hartle ranked 36. During the treatment, Tobin asked him to rate his anxiety again. Hartle reported a zero. No anxiety. The day after the trip, he scored a mere six points: mild anxiety, verging on nonexistence.

Hartle hasn’t suffered a panic attack since the treatment. He has become more open with people around him and even learned to view his chemo treatments with grace. “To be fair,” he confesses, “everything about chemotherapy does kind of suck. But as opposed to dwelling on it, I have just experienced it and let it go.”

It’s too soon to speculate on how the rush of investors will shape the next phase of this psychedelic renaissance. What’s becoming clear, through all the hype and hallucinatory reveries, is that for patients suffering from acute anxiety and end-of-life distress, psilocybin offers serious, long-lasting relief, making those last days more livable. For patients like Brooks and Hartle, there are still bad days. But, as Hartle himself puts it, in what could stand as a tag line for a whole new wave in psychiatric medicines, “The bad days are better.”

The post Magic Mushrooms May Help People with Terminal Cancer appeared first on Reader's Digest.